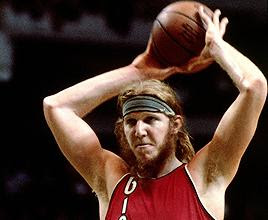

Bill Walton’s Back from the Dead: How the difference between 88 and 105 can be tinier than a foot fracture but hurt even worse

21.

He peaked way, way, way too soon.

History, and biology, chose Bill Walton. A different time, a different size, and he is not one of the world’s most fascinating and awe-inspiring individuals.

But Mother Nature brought him into this world in 1952, with DNA (by most educated guesses) to exceed 7 feet, in Southern California, not far from where a 40-something fellow named John Wooden was putting together a decent college basketball program.

Together they achieved staggering success, somehow culminating in almost unthinkable setbacks.

There’s a strong case that Bill Walton is the greatest to ever play basketball. Stats favor a handful of other players, but Walton’s excellence must be observed, not calculated. In his prime. In other words, 21.

Sadly, what nature giveth, nature taketh away. Walton’s greatness was offset by rapidly deteriorating physical problems. That’s not his greatest pain. Today, in his 60s, what seems to sting most is a spectacular record that somehow feels incomplete.

Walton matter of factly discusses his highs and lows — there are many lows — in his 2016 autobiography, Back from the Dead. Most of the material breezes gently from one story to another, with notable candor. A few passages receive not so much extensive wording but obvious thought, as in, he has clearly worn out this subject in his mind, for decades, the type of obsession many of us know all too well.

Back from the Dead is a remarkable warning of underachievement — that it strikes even the greatest, or maybe is even more likely to happen to the greatest, possibly through no fault of the underachiever. That its effect is disproportionate to success; as one example, 2 perfect seasons barely equal 1 January defeat in South Bend. That Walton’s own organization most likely was guilty of the same kind of arrogance as the U.S. government that Walton was vigorously protesting.

The book is ground-level recollections. Walton doesn’t ruminate on the bigger picture. Athletically, he is a figure of enormous success and equally enormous tragedy. Not only a giant of his sport, Walton is also a face of America’s tumultuous transformation from the “Greatest Generation” to everything since, that period of time from roughly the JFK assassination to Nixon’s resignation in which American attitudes and pop culture changed profoundly forever, the nation’s biggest divide between old and young, when athletes’ crew cuts gave way to long hair, one of Walton’s specialties. Guided by the sport’s greatest teacher, Walton would gradually find himself at odds with his mentor, prevailing philosophically, with latent regret, because, like others of his age, he was right, about most things.

Though Walton has become a gifted broadcaster, it would be pointless to ask him — or any athlete — to describe his enormous talent. It is like asking actors why they are good actors. The truth is, they just are. Explaining why they can make a better face on camera than someone else is impossible. Walton in Back from the Dead does not attempt to explain his strengths or weaknesses as a player, only how it all made him feel.

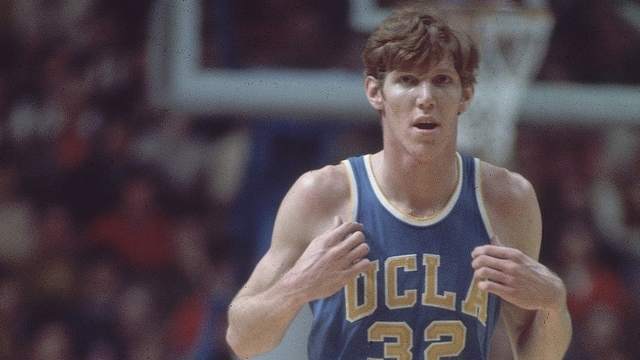

Bill Walton would front the most dominant athletic machine of American history. The number that matters most is 88. It is not his alone but is largely and accurately attributed to him. The greatness of Bill Walton, however, is best appreciated by watching, for those fortunate to have seen the games live and all others who can look up the disappointingly rare clips that exist on YouTube.

Winning is a big deal, but pop culture only cares about how a team wins. Walton’s UCLA was basketball’s equivalent of the ’27 Yankees, and Walton was The Babe, except the ’27 Yankees 1) weren’t booed by 5,000-15,000 screaming 20-year-olds and 2) actually lost some games. A fever pitch greeted the Bruins at opposing arenas. Game after game, Walton’s team couldn’t be beat. UCLA victories were virtually trees falling in forests. The same was mostly true a few years prior when Kareem Abdul-Jabbar led the Bruins. But Jabbar was a serious, New York import who wasn’t exactly having the greatest time in college. Walton had the time of his life and, until about January of his senior year, wore it on his sleeve with SoCal cool.

Walton handled the ball like a guard, rebounded at will, unleashed cannon shots for outlet passes, intimidated elite opponents. On a team with several other All-Americans, he led the squad — easily — in points, rebounds and assists, which UCLA apparently only started publishing in 1974. No big man has ever played basketball with this kind of skill.

It has to be seen to be believed.

And just when it was all getting started, it was crumbling.

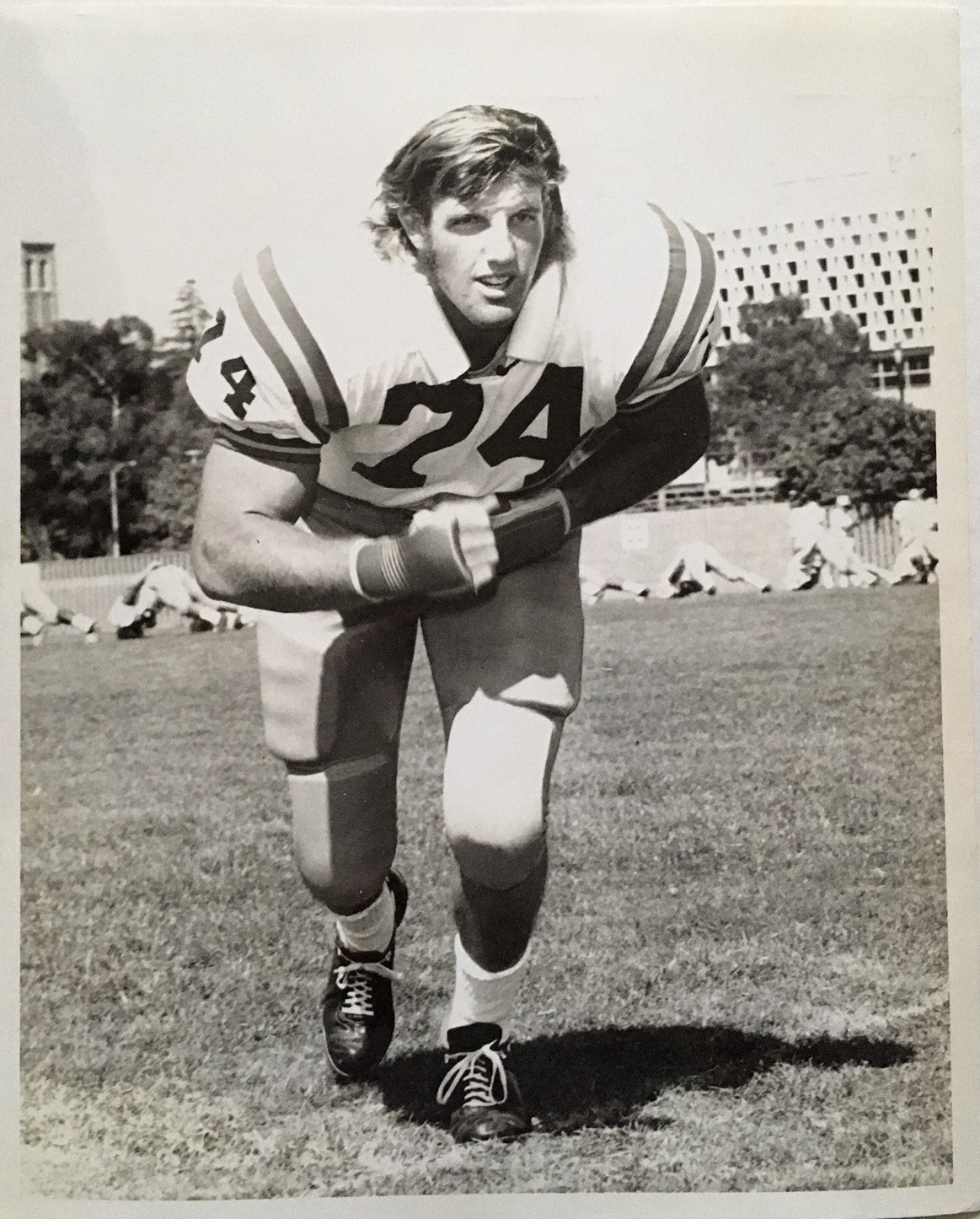

Bruce Walton at UCLA in 1972.

In the beautiful randomness of life, fluky things happen. According to Walton’s account, his parents were “the most unathletic people ever.” Somehow, they produced not only Bill, but a 6-6 brother, Bruce, who would play tackle in the NFL.

Here’s something the brothers got besides size — an edge, the psychological difference that separates 1-in-a-million players from great athletes.

A native of San Diego, Bill Walton writes of being unusually talented by age 14 and indicates that jealousy among older players in a pickup game prompted them to “take out” his legs, tearing a ligament in a knee and permanently impairing his ability to run. But it was a remarkable growth spurt in high school that put him on the nation’s basketball map and caught the eye of UCLA, the royalty of college basketball which at the time was only in the early stages of a jaw-dropping streak of NCAA championships that could hardly be believed if it wasn't on film and in the record books.

The name “Bill Walton” (referring to the basketball star) first appeared in the New York Times on Nov. 29, 1970, the beginning of his freshman season at UCLA, according to an online search. That the mention isn’t earlier is significant. Walton, certainly a coveted prospect, had not achieved the prep hype of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (no one probably has, before or since), of New York City, or perhaps even later Southern California legends Tyson Chandler and Schea Cotton and Stuart Gray. Walton was a “spindly” 6-6 as a high school sophomore and was said to reach possibly 6-9 as a junior. It happens in every sport — some players mature physically at an early age, maybe mid-teens, and appear to be inevitable greats, while others are still growing and surpass them around age 18 or 19. In the fall of 1970, freshmen were ineligible for varsity sports, an NCAA rule for the players’ own good, of course. It appears that Bill Walton soared from prized recruit to bona fide superstar after one year at UCLA. A New York Times profile in December 1970 of the 1970-71 varsity team only mentions Walton near the end, in a quote from Wooden with a notable reference to size: “That’s our 6–10 freshman center, Bill Walton,” Wooden said to the reporter. “He could be a superstar.” According to the 1973 book The Wizard of Westwood by L.A. sportswriters Dwight Chapin and Jeff Prugh, Walton as a freshman “showed only glimpses of the greatness” he would soon possess and “improved markedly” as a sophomore.

Walton arrived at UCLA not long after the departure of Jabbar, the most celebrated college basketball recruit of all time who chose Westwood and delivered 3 national titles in a near-perfect 3 years in the late 1960s.

But UCLA had won 2 titles shortly before Jabbar arrived, and, incredibly, the next 2 afterward. UCLA won with Jabbar, won with small teams, won with forward-oriented teams. The common denominator of the school’s extraordinary success wasn’t Jabbar, but Coach John Wooden, already every bit of 59 when Bill Walton arrived on campus in 1970.

Wooden was born in Indiana, on a farm without electricity. He was no 7-footer (actually 5-10) but a remarkable athlete, the college basketball Player of the Year at Purdue, long before the organization of basketball on a national scale. He would serve in the Navy from 1943-45, teaching physical education, apparently not sent to the South Pacific because of appendicitis.

Before Walton’s arrival, Wooden was regarded as the game’s preeminent teacher; the first in the Basketball Hall of Fame as both a player and a coach. He had an edge, too. But he was the salt of the earth. He married his high school sweetheart. Proudly never swearing, he garnered attention for his Pyramid of Success and oft-repeated quotes about humility and hard work.

One wonders, after 7 national titles, if he knew what he was in for.

Since the mid-1960s if not earlier, the popularity of college basketball has turned a fair number of 17-year-old males into objects of worship, attracting proud grown men of significant stature to their homes like shameless beggars. Given these players’ impact on a university, there has been, and will continue to be, healthy debate over whether they should be treated as professionals. That day has not yet come. In 1970, attitudes were light-years from today.

About any coach in America who recruited Jabbar or Walton would’ve been beholden to the athlete, fearing any disillusionment that might cause the player to transfer or turn pro — except John Wooden, because Wooden himself was possibly the greatest basketball player in the nation at one time. No other elite coach — in any sport — in American history achieved such stature. John McGraw? An exceptional player, he won 3 World Series crowns in 32 years as skipper. Lombardi? A Fordham “Block of Granite,” but nowhere near the player résumé of Wooden, and his 5 NFL titles were won by largely the same group of players in about an 8-year span. Wooden coaching UCLA to 10 NCAA titles is like if Roger Staubach had taken over USC football in the 2000s and won 3 times as many BCS championships as Pete Carroll. Though known for his humility and values and expressions sometimes considered (as in Back from the Dead) folksy or silly or even condescending, Wooden should be better known as an enormously powerful figure, a general of human beings. This is the only person on the planet who could, and did, order Bill Walton what to do. Chances are, had Jabbar or Walton grown disenchanted enough to tell him goodbye, Wooden would’ve simply responded, “See you in the Final Four next year.”

When Jabbar and Walton were at UCLA, tens of thousands of Americans were dying in Southeast Asia. This was the end of the time when even the greatest college athletes had to cut their hair and tell the coach “yes sir,” an era when someone of Wooden’s position would actually admit, “I would discourage anybody from interracial dating.”

Despite Wooden’s phenomenal success, the world off the court was rapidly passing him by. It can be said that Vietnam like no other American issue drove a stake between generations, that those born before 1930 were much more inclined to back the war effort while those born after 1940 were typically anything but. Wooden was born before California Gov. Ronald Reagan. Whether Wooden thought Vietnam was the right idea won’t be speculated here, but overseeing basketball players who identified with protesters was definitely not part of the game plan. It was the gold mine of UCLA basketball that kept him going. Curry Kirkpatrick wrote in Sports Illustrated’s 1970-71 season preview that “any talk of retirement has been delayed due to the brilliant freshman team,” featuring Walton.

At that point, UCLA might have been the IBM of college basketball, its toughest opponent not on the schedule: indifference. Despite its staggering collection of victories, to this day, the 3 most famous UCLA basketball games are all defeats, 2 of them featuring Bill Walton. Kirkpatrick in 1970 noted that in Los Angeles, “Some of the zeal for the team has naturally subsided in direct proportion to the boredom caused by winning so regularly.”

By Bill Walton’s arrival, Wooden’s UCLA resembled the contract law classroom of Professor Kingsfield in “The Paper Chase,” a film perhaps not coincidentally released in 1973. Kingsfield and Wooden are former prodigies, figures of immense stature and impeccable credentials. Many of the top talents in the country arrive to learn from them ... a few, perhaps, to challenge them. Bill Walton, like James Hart, pushes the envelope. They know they’re good. Each could say “Yes sir,” do as told, look forward to a highly successful life. But each has a rebel streak that won’t let it be that simple. What do they gain from a challenge? They just can’t help themselves.

Walton was able to take the court for UCLA’s varsity in autumn 1971. That his predecessors won the school’s 5th straight NCAA championship was not a surprise. That they handed him a 15-game winning streak is remarkable. Losing at Notre Dame midseason, the 1970-71 Bruins, led by college Player of the Year Sidney Wicks, of Los Angeles, ran the rest of the table, including a perhaps improbable victory over No. 2-ranked USC at the Sports Arena after trailing 59-50 with 7 minutes left. Three more conference games, and a West Regional nail-biter vs. Long Beach State, one of the most famous games of Wooden’s tenure, were decided by 2 points or less before the Bruins hoisted the school’s 7th title in Houston, all while young Bill Walton was relegated to harmless freshman exhibition games.

Possibly, that UCLA varsity might have faced its toughest opponent in its own practices. Wooden told the New York Times in 1970 that Walton scrimmaged two days a week with the varsity. Walton writes that playing against Wicks, “I was blocking shot after shot after shot of his.” Reflecting the subtle arrogance of the program, Walton writes, “Our practices and drills at UCLA were the most demanding, most challenging, and toughest basketball I have ever played.”

Things only got better as autumn 1971 arrived. Instantly, Wooden and Walton produced the greatest team college basketball has ever known. Santa Clara coach Carroll Williams bluntly told Chapin and Prugh, “He’s the best college basketball player I’ve ever seen. He’s better at both ends of the court than Lew Alcindor was — he dominates like no college player in the history of the game. And that includes Bill Russell, whom I played against.”

There were 30 games, and none were in doubt. Walton and fellow star sophomore Jamaal Wilkes, plus a third elite member of their class, Greg Lee, joined senior holdover All-American guard Henry Bibby and wings Larry Farmer and Larry Hollyfield. The Bruins topped not 100 but 110 points in 5 straight games and beat Notre Dame by 58. The closest game was a 5-point victory for the national title over upstart Florida State. That outcome so unimpressive to Walton, he told reporters, “I felt like we lost it,” an early hint of big-game complacency that would dog the Bruins 2 years later.

According to Sports Illustrated’s account of the NCAA championship, Walton “gave a few ‘no comments.’ He snapped off tart replies. He was sarcastic, defensive, and he stormed off muttering, ‘I’ve answered enough questions.’ ... ‘We don’t like to back into things,’ he said. ‘We didn’t dominate the way I know we can.’”

In his book, Walton notes that, this being a championship game, Wooden allowed the press to ask Walton questions, “which was not a good idea,” because after being honest, “I was universally vilified as an ungrateful ogre.”

There was another issue in 1972 that might’ve rubbed some basketball fans the wrong way and, incredibly, nudged Bill Walton into the Cold War.

Walton writes of a troubling experience playing for the U.S. national team in Europe in 1970 and somehow being rarely used by tyrannical coach Hal Fischer. When 1972 came around, Walton was the prized recruit for the U.S. Olympic team that would compete in Munich in hope/anticipation of extending ... the nation’s undefeated streak.

Walton says he met with Olympic officials in Wooden’s office and that Wooden “had not had the best experience with the Olympic basketball people” since Gail Goodrich did not make the 1964 team. Walton writes that despite UCLA’s enormous success, Walt Hazzard was the only Bruin to “make” the Olympic team, ignoring that Jabbar, as black athletes in 1968 talked of boycott, declined to play in the Mexico City Games while insisting he wasn’t taking part in a boycott.

Walton writes that in 1972, he gave the Olympic officials several demands: He be automatically on the team and not need to try out, that he wouldn’t play exhibitions beforehand, and as soon as the Games were over, he’d be out. He said the Olympic guys said no. And Walton never gave it “another thought.”

Chapin and Prugh in The Wizard of Westwood write that, “Ostensibly, Walton said no because his tender knees probably could not withstand the punishment of nine games in eleven days” but that it’s reasonable to think Walton’s political and social views “weighed heavily.” Wilkes also declined to try out. Walton’s backup, Swen Nater, later a fine NBA player, tried out and made the team, which could’ve been a fine showcase for an elite player totally obscured by Bill Walton. A big man such as Nater would’ve been greatly needed in the final game, but he left camp over disagreements with coach Hank Iba.

Without Walton, Nater and Wilkes, the U.S. team, which had built a 63-game winning streak in Olympic basketball, “lost” history’s most dubious basketball game, the gold medal match with the Soviet Union.

Walton does not use quotes around the word “loss.” Reflecting the perhaps fatal conceit of the UCLA program, Walton writes that the Olympic organizers never suggested designating the UCLA team as Team USA and simply sending the Bruins to Munich, “And then, most assuredly, the United States would have won.” In a 2002 HBO documentary on the game, Soviets mock the fact Walton had other things to do that summer.

For many Americans, time and the creation of the 1992 professional “Dream Team” have erased the wound of this game. Walton barely mentions the topic and expresses no regrets. This was the time to err on the side of questioning authority and national leadership: “It is impossible to come up with a greater moral and ethical divide in my lifetime than what was done in our name in Vietnam,” Walton writes.

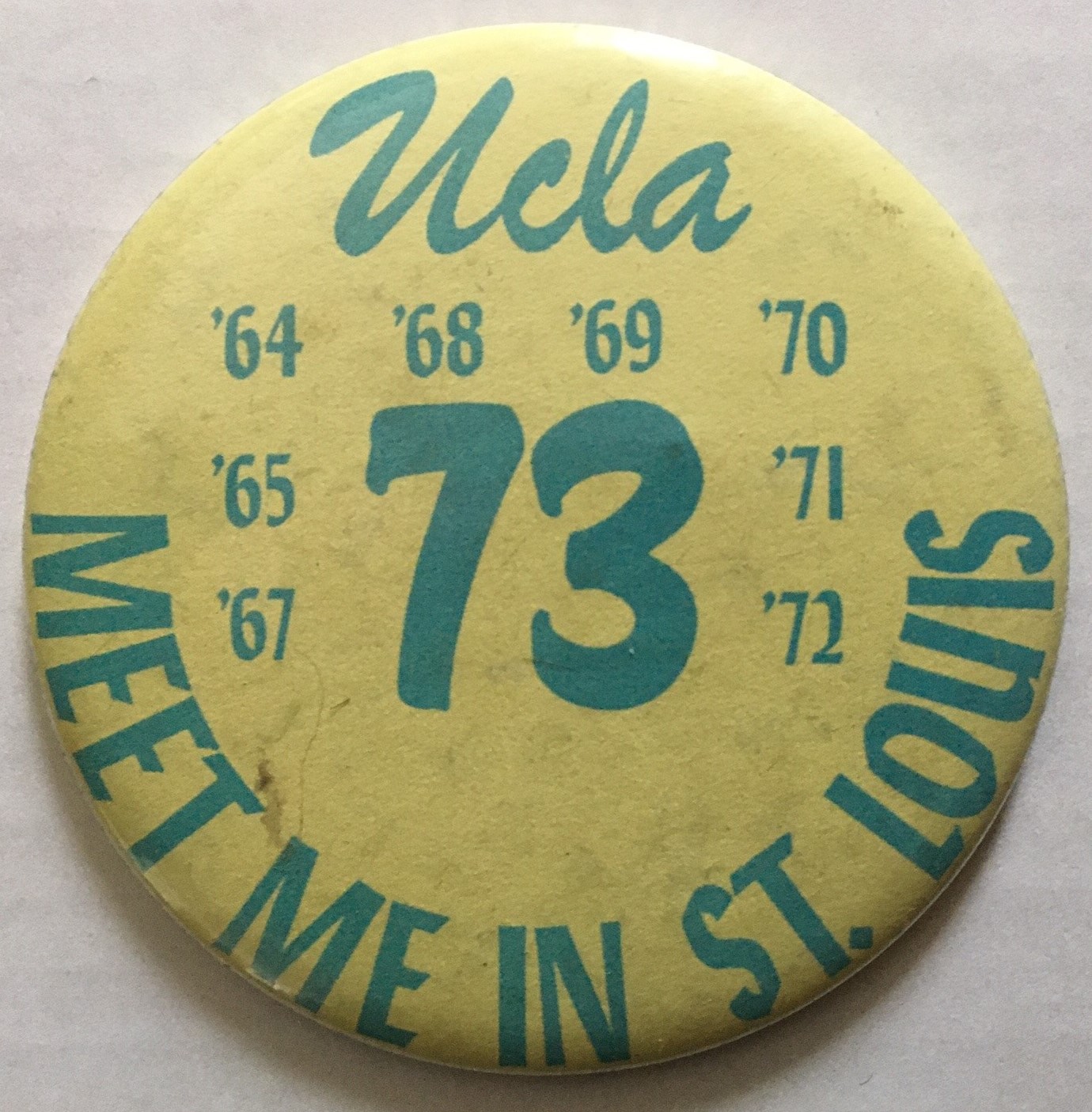

UCLA’s 1971-72 title season pushed the winning streak to 45. The NCAA record was 60, set by Bill Russell and K.C. Jones’ San Francisco teams. Jabbar’s teams had peaked at 47 straight until the Game of the Century upset in the Astrodome in 1968. In interviews during the 1972-73 and early in the 1973-74 seasons, UCLA players insisted they didn’t think about the streak. Wooden in the UCLA 1973-74 media guide acknowledges “some pressure on us last year” as the streak, which included not even a single overtime game, neared 60. Whatever the approach, it worked. They won No. 61 easily at Notre Dame midway through the 1972-73 season. Kirkpatrick in Sports Illustrated wrote that win No. 61 came “without much sign of effort.” The season ended with another 30-0 record and minimal to no drama. It concluded with Walton’s finest hour, a 21-for-22, 44-point effort in the NCAA championship that is surely the greatest amateur basketball performance ever.

At that moment, Bill Walton was undeniably bigger than college basketball, too good for the competition, and, most importantly to Wooden, too free-spirited for the chain of command. It was the perfect time to go — a perfect game, a perfect record, a perfect streak that stood at 75.

But in 1973, it was rare for elite college players to turn pro before graduation. Some did, citing family economic “hardship” or simply because they weren’t interested in college. Neither circumstance applied to Walton. Still, there was an ABA as well as an NBA and an unfolding sports economic landscape. Interviewed by Tommy Hawkins on the court after the 1973 championship, Wooden said he believes Walton will return for his senior season. “He indicated to me, uh, even as late as this morning, that he was looking forward to playing at UCLA next year. And he’s never given me any other idea. And all this, uh, that you hear outside, I think is just supposition, maybe wishful thinking on the part of some people,” Wooden says.

Perhaps to prove that point, Wooden, according to Walton’s account in Back from the Dead, insisted in the locker room that Walton meet representatives of the ABA that night, despite Walton’s protestations; the coach said Bill owed them “the courtesy.” According to Walton, the representatives promised him part ownership of an L.A. franchise, told him he could pick the roster from the rest of the ABA except for Julius Erving, suggested Jerry West would coach the team or serve as GM, and finally “opened up the suitcases, which were filled with cash.” Walton writes that he shrugged and told the representatives that he couldn’t be happier at UCLA. “I never gave any of it a first thought,” he writes.

The NBA would’ve been more complicated. Like Jabbar years earlier, Walton would’ve been beholden to an absurd draft system that in ’73 gifted the awful Philadelphia 76ers with the exclusive rights to the No. 1 pick. Walton writes he would never go there. A year later, Philly would lose the No. 1 pick in a coin flip to Portland. Both franchises would meet just 3 years later in the NBA Finals.

Principled about politics, Walton evidently never felt the same way about business. He would sweat the small stuff in college and ignored the big stuff in the pros — that he couldn’t choose his own team, that players had limited rights.

Walton liked college and California too much to turn pro. But with the streak at 75 and limitless, the college basketball world had seen enough. In Sports Illustrated’s preview of the 1973-74 season, Kirkpatrick laments the predictability of the Bruin dynasty and bluntly declares, “May they have no more.” Kirkpatrick rightly speculates that the ACC, with several elite teams, could topple the Bruins in a Final Four matchup in friendly Greensboro. What’s lacking in the article is any kind of reason why the Bruins might stumble.

Under the surface, there might have been signs of trouble in 1972-73. The Bruins’ scoring dipped noticeably, from 2838 in 1971-72 to 2440, and their average margin of victory fell from 30 to 20. That could be attributed to the 1972 graduation of Henry Bibby, Wooden’s last All-America guard, or to frustrated opponents employing more stalling and aggressive strategies. Jabbar’s teams posted 26-point margins his first two seasons and 21 points in his senior campaign.

An interesting trend through Wooden’s astounding 12-year title run is that the newest teams were the best teams. The only thing that could stop this program, it seems, was senioritis. Jabbar’s ’67 squad outperformed the ’69 version. The Wicks-Rowe-Patterson crew breezed to the 1970 crown and then clawed through a couple of very close games to prevail in ’71, notably the West regional thriller against Long Beach State as well as the title against Villanova, the closest of the 7 straight championship games. The 1974 team? Consider that they couldn’t win the title, but 4 guys sitting on the bench won it the next season.

In UCLA’s 1973-74 media guide, Wooden says the previous season was one of the most “trying” of his career, in part because of “the publication of several books pertaining to UCLA basketball and my personal life.”

Walton makes no mention of such off-the-court concerns in Back from the Dead, writing that, entering the 1973-74 season, “This was by far our most talented team in the four years that I played for UCLA.” That is true in terms of pure talent and NBA potential. But the Bruins were top-heavy in the frontcourt and had a problem at guard. Wooden no longer entrusted the offense, or even a permanent starting position, to Greg Lee, Walton’s friend and running mate. Instead Wooden used a rotation of Lee, Tommy Curtis, Pete Trgovich and Andre McCarter.

UCLA players regularly shrugged off the streak. How much did they worry that paradoxically, if this incredible streak ended on their watch, it may haunt them forever?

Apparently little. Walton writes, “I was in top shape and form. ... The concerts and special events continued unabated, and I was into everything.” And, “When we officially got going with the team ... we were all so very excited, dizzy with the possibilities of the pending perfection and the chance to run the table.”

That feeling evidently didn’t last.

In numerous interviews, Walton blames himself. In 2010, he told the Los Angeles Times, “I stopped listening to the coach. I stopped my dedication to the team goals that made us undefeated champions the previous two years and I let John Wooden, UCLA, the NCAA and the game of basketball down. I didn’t get the job done. We had a chance to do something really special at UCLA. It’s my fault we didn’t.”

But in Back from the Dead, Walton implies that the downfall of the 1973-74 team was a clash of wills between coach and players. Walton writes that on the first day of practice, Wooden “basically threw me out of practice before it even started” because of allegedly too-long hair and not shaving. Walton dashed out, got a shave and a haircut, and missed 3 minutes of practice.

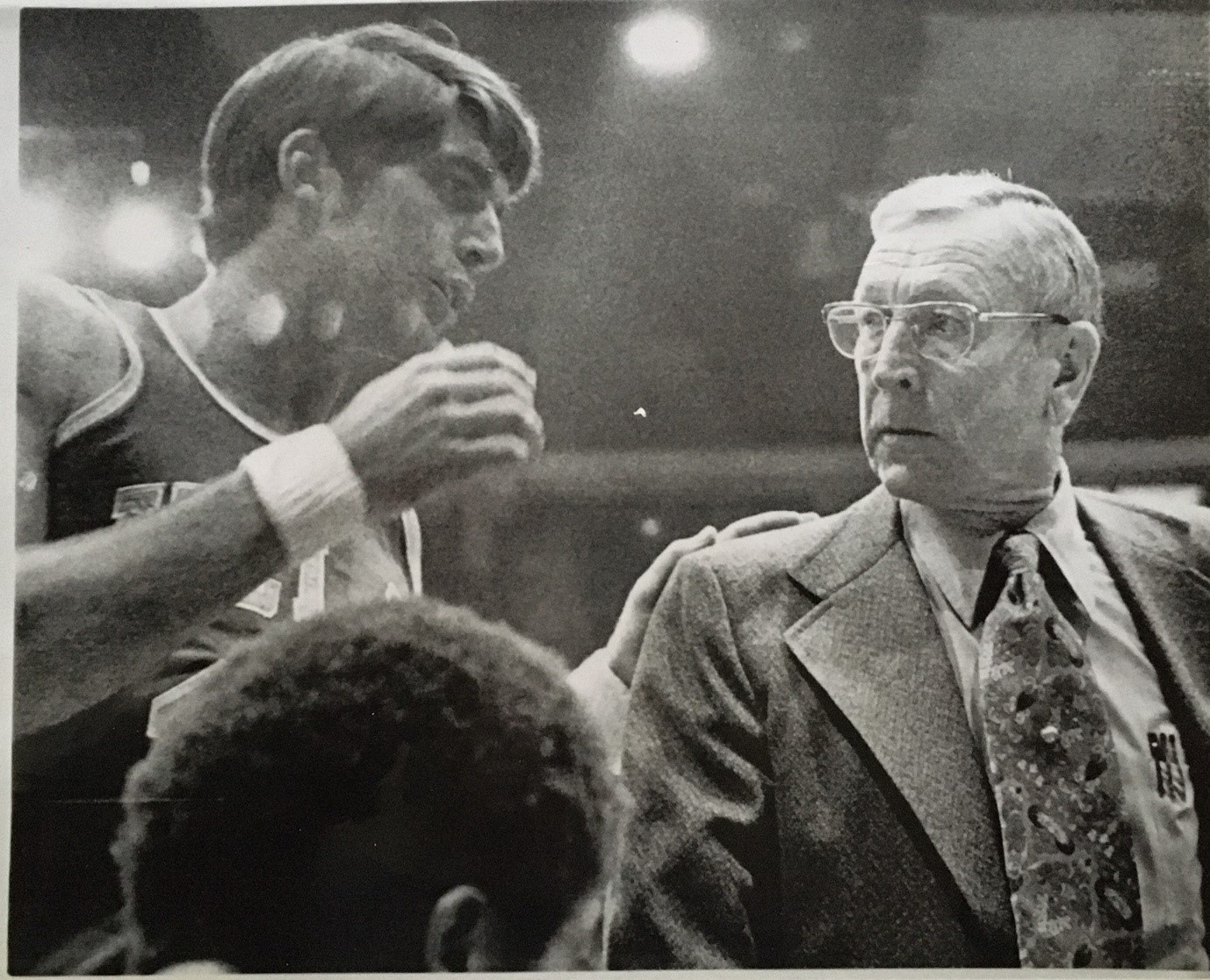

The bigger confrontation, according to Walton, came in an early practice when he noticed Wooden and Lee having an “unusually contentious” conversation on the other side of the gym. Walton writes that afterward, Wooden proceeded to stride right over to him and declare, “Bill, it has come to my attention that you have been smoking marijuana.” Walton replied, “Coach, I have no idea what you’re talking about.” Wooden said “Good,” turned away, and apparently the matter never came up again. But Walton writes that Lee experienced a similar conversation, and, “Whatever Greg’s answers to Coach were that day, things were never the same again.”

(A Sports Illustrated account from 1989 states Walton actually asked Wooden for “permission to smoke marijuana,” and it was, more or less, not given.)

In 1974, according to teammate Marques Johnson in 2004, Walton was “always challenging coach Wooden.”

There were the Coach’s decisions on playing time. “I’ve concluded there was nothing as devastating as the continued presence in the lineup of Tommy Curtis,” Walton writes.

“I would be in Coach Wooden’s office, pleading, explaining, begging for sanity, rationality, reason. But all to no avail. As Greg sat for extended periods and Tommy continued to get more and more of everything, Coach would just sit there with a blank stare as I tried to get him to see what was so painfully obvious to me.”

Wooden apparently began to favor Curtis over Lee. But at times, they played together, as Wooden gave significant time to 4 guards. While Walton bluntly airs his opinions, there is likely more to the story. Lee was a skilled passer who glorified Walton; Curtis was a better scorer who liked to shoot. And Lee is white, Curtis black. Look up in-depth articles about locker rooms in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and one finds the issue of race inescapable, even at Jackie Robinson’s alma mater of UCLA, factors that might have influenced Wooden’s decisions on playing time.

Only months after graduating, Jabbar wrote an essay for Sports Illustrated titled “UCLA was a mistake,” explaining that to some people he met in California, “deep down inside, I was nothing but a jive n-----.”

(Jabbar also wrote that “Another thing that bugged me was the way the kids seemed to think that they could make any comments they wanted about my height,” a problem never mentioned by Walton in Back from the Dead.)

A 1973 Sports Illustrated article notes Curtis “was disturbed by the pressures in high school, but he says the hardest times of his life awaited him at UCLA. ‘The subtlety of racism here is ridiculous,’ he says. ‘I wish I could tell some people how to do it; they don’t even know how to be prejudiced.’ ”

The Lee-Curtis controversy is not unlike that of “Any Given Sunday,” a 1999 film by Oliver Stone. In “Sunday,” a fading white quarterback attempts to keep his starting job despite injury and the potential of a young black quarterback with a different skill set. Both Curtis and Lee were high school greats and would be drafted by the NBA in the 7th round of 1974. Who was the better player? There’s a valid argument on either side.

Maybe it had nothing to do with it, but Curtis is also a Republican. Walton doesn’t declare a party in Back from the Dead but makes repeatedly disparaging remarks about Nixon and Reagan; draw your own conclusions.

While Walton implies that Lee was punished, and lost out to Curtis, for non-basketball reasons in the 1973-74 season, the SI account by Curry Kirkpatrick of the 1972-73 squad suggests the team already dealt with this problem, noting Lee “had lost his starting position to Tommy Curtis and playing wasn’t fun anymore,” and that “Lee has a mock certificate from the ‘Curtis Fan Club’ sent to him by a former roommate.” Kirkpatrick wrote that Lee “is slow,” which is why Wooden would prefer Curtis for the fast break and press defense.

Recapping the 1972-73 season in the Bruins’ media guide, Wooden singles out Curtis second only after Walton for his “inspirational and effective play on many occasions.” According to the media guide, Curtis started the first 10 games of 1972-73 but missed the next 6 games because of illness and never regained the starting job that season.

Walton writes that Curtis was a “self-centered, overdribbling, statistically oriented, loudmouthed, foul-mouthed fool.” But Walton also writes that, after just his first varsity game, Lee made Wooden “furious” by telling sportswriters that the overmatched opponent, The Citadel, was “like one of the junior college teams we played last year as freshmen.” (Chapin and Prugh in The Wizard of Westwood write that Wooden berated Los Angeles Herald-Examiner writer Doug Krikorian at a luncheon for the quotes attributed to Lee and for trying to “pull things out of our players” but apologized for the outburst a week later.)

Wooden might’ve been irritated that Lee, as a freshman, stood and applauded when graduating reserve Bill Seibert delivered a famously scathing critique of Wooden at the team’s end-of-season banquet in 1971.

Whatever the egos and controversy, UCLA kept winning and kept ignoring opponents. Soon the streak had reached 88, a beautiful number that figured to be just a momentary steppingstone. It became much more than that and a number Bill Walton apparently hates, because — in a powerful lesson about quitting while one’s ahead — “it should have been 105.”

Oddly enough, for a completely different reason, it should have been at least 108. Walton accepts the strange rule of the time, that freshmen should be ineligible for varsity college athletics. Had he and Wilkes played on the 1971 team, it’s highly possible that squad would have gone undefeated.

Rather than Tommy Curtis, it seems it took 3 factors — complacency, injury and location — to topple UCLA. It happened in 3 phases, all far from home in very hostile environments: The streak-breaker at Notre Dame; the “Lost Weekend” in the state of Oregon that suggested the Bruins were no longer infallible and might not even make the NCAA Tournament, and the meltdown in raucous Greensboro that ended the national championship streak. Maddeningly to the Bruins, they played all 4 of those teams twice that season and won those other games handily.

Greg Lee and John Wooden during UCLA's 68-44 win

over Iowa on Jan. 17, 1974, at Chicago Stadium,

the last victory of the 88-game streak. AP Photo

On paper, the Notre Dame defeat is very understandable. 1974 Notre Dame, finishing the season 26-3, was likely one of the 5 best teams that Walton’s Bruins played in 3 years. The Irish had an electric home court. It was Walton’s first game after he suffered a “broken back” about 2 weeks earlier in Pullman when a “thug” from Washington State in a “despicable” act undercut him around the rim. It’s the way this game was lost that is jaw-dropping: a 17-point first-half lead; an 11-point lead with 3 minutes left, squandered. Typical Bruin domination of a very good opponent. Somehow, this time, unable to seal the deal.

The end of the Notre Dame game indicates something far more wrong with this ballclub than personality issues with Tommy Curtis. Curtis scored the Bruins’ last points, making the score 70-59. In the remaining 3½ minutes of atrocious basketball, Curtis, Dave Meyers and Jamaal Wilkes were, equally, a collective disaster, and Walton was irrelevant on both ends of the court. It was something like Mariano Rivera’s inexplicable 9th-inning fail in Game 7 of the 2001 World Series. Wooden’s crew had no idea whether to milk the clock (yes) or attempt awkward shots (no). They called timeout with 21 seconds and the ball and trailing 71-70, yet appeared to be clueless about how much time was left even after the Irish knocked a rebound out of bounds. Walton’s last shot was rushed after an awkward hop. One can only imagine how many similar games had been won in these circumstances by John Wooden’s teams in the previous 7 seasons, as well as the NCAA Tournament games in the following one. Wooden tried to shrug off the loss in comments after the game, saying, “Once we got the game to break the record, it was relatively meaningless. We knew it would end sometime. Now we have to win our conference to defend our national title.”

If those ’73-74 Bruins were allowed a do-over of any loss, the guess here is that they would pick the Notre Dame game. As a non-conference, regular-season matchup, it was the most irrelevant of the 4. (It was not a big enough deal to make the cover of Sports Illustrated, which happened to be the swimsuit issue graced by Ann Simonton, or more specifically, Simonton’s posterior.) Psychologically — and only the UCLA team would know for sure — it was likely the most devastating, bursting the notion of UCLA invincibility and removing a key incentive for these Bruins, who had seen and done it all, not to be jaded. There were a few big victorious routs afterward, but the pair of losses in Oregon can only be described as “flat” performances. That was not the case in Greensboro, but an 11-point 2nd-half lead (and, incredibly, 7-point overtime lead) evaporated at the hands of an opponent who simply wanted it more.

The streak nearly ended at 76, when the Bruins struggled at Pauley in the highly anticipated Game 2 against 4th-ranked Maryland, preserving a 65-64 win with a late steal by Dave Meyers. Walton “struggled” in that game, making only 8 of 23 shots ... but collecting 20 rebounds in the first half against Maryland’s ballyhooed front line of Len Elmore and Tom McMillen. That game foreshadowed that the ’73-74 Bruins, on multiple occasions, would solidly outplay even the best opponents for 30 or 35 minutes, only to be grossly outplayed in the final moments.

Maybe there was another culprit — arrogance. It is with some irony that as Southeast Asia (and other issues) divided players and coach, UCLA collectively on the court maintained an approach to its opposition eerily similar to the U.S. government Walton despised.

Players were well aware of Wooden’s emphasis on drills and practice and not the other team. He presumed his opponents beneath his attention. Walton writes that in his time in the program, Wooden almost never mentioned opposing players by name. “In my four years at UCLA he did it twice.” Those were Austin Carr and David Thompson, who spearheaded dramatic upsets in 1971 and 1974.

In a 1989 interview, Greg Lee says, “Half the time we didn’t even know who our opponent would be.”

Prior to the 1974 Notre Dame loss, Wooden had said, “I haven’t seen Notre Dame play. I did talk to a friend about them, not a basketball man, just a friend.”

Said reserve guard Andre McCarter before the 1974 Notre Dame loss, “We look at it like a business, like a job. That’s how it is at UCLA.”

But not always. In Kirkpatrick’s details of Win 61 in South Bend, Walton had “the flame in his eyes,” according to Wooden, which no doubt inspired the easy win ... but he apparently still had it while on the bench at garbage time, as he “continued to razz Notre Dame,” according to Kirkpatrick.

The Final Four showdown with North Carolina State almost never happened, as UCLA ran into unexpected trouble in its first tourney game against Dayton. Wooden used a revolving door at guard, and the Flyers in the second half thoroughly outplayed the Bruins, who trailed most of the last five minutes of regulation. Walton’s numbers (27 points, 19 rebounds) were sensational, but he missed a lot of shots, and it was Dave Meyers who made a couple big plays late to send the game into overtime; UCLA finally prevailed in triple overtime, 111-100. In Greensboro, the Walton Gang met David Thompson, according to Walton, the best college opponent he — and perhaps the UCLA program — ever faced.

It is surely a fair argument to claim that the Notre Dame and North Carolina State teams of 1974 were better than UCLA, although objective evidence — the fact the Bruins handily beat each once and just barely lost once — would seem in UCLA’s favor. But Oregon and Oregon State? The snapping of the streak hints at something psychologists might deem unthinkable — is there ever a time when human beings want to lose? (That is not to say they are trying to lose but are simply content to do so.) And not just when they’re playing their younger brother, but random opponents?

Perhaps. Golfers, for example, might actually prefer to miss a cut and have a weekend with family rather than compete in another tournament. Baseball players with plans for the evening might prefer to lose 3-2 in the 9th rather than force extra innings. If players think they are being wronged or underappreciated or mishandled by a coach, then a loss might be an extremely subtle passive-aggressive weapon — “This is what you get for restricting me or my friends in some way.” In the Sports Illustrated 1973 Win 61 profile, Kirkpatrick wrote that UCLA players thought a “certain segment” of fans, namely well-heeled alumni, were a bit too fair weather, and the players wondered about reaction to a defeat: “They seriously doubt the loyalties would be lasting.”

Not only that, but a coach frustrated with certain players might quietly wish other teams would provide the comeuppance for a change. Chapin and Prugh in The Wizard of Westwood suggested that Wooden “secretly wishes” for an occasional defeat. They quote the coach: “Sometimes I think we needed to be knocked down to win later on.”

And there’s another possibility. People like drama and detest boredom. Losing a game (or 4) was about the only way UCLA players could experience the former. Think of that near loss to Maryland in late 1973, a game virtually no one remembers but that everyone would remember if Maryland had won. Try naming the teams Jabbar beat in the Final Four. Then name the team that beat Walton. Was it so devastating at the time? After the 1974 Final Four loss, Kirkpatrick writes in SI that Walton “sat nude in the dressing room refusing to talk to the press, grinning like a Cheshire cat.”

And so Bill Walton came up short to both John Wooden and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in one notable category: A happy ending. In his 60s, Walton says, “I look back at my college career as one of frustration, disappointment, and ultimate embarrassment. For us to give 4 games away out of our last 10 (actually 16) was just totally unacceptable. And I will never be able to erase the stigma and the stain from my soul about what could’ve been. We could’ve been perfect.”

Entering the NBA Draft, Walton admits, “Everyone kept asking me what I wanted, and I didn’t know.” That one’s on him. This is someone who writes of himself as a Rhodes Scholar candidate. As one of the extremely rare, once-in-a-generation college basketball or football players in the last 50 years, Walton had the opportunity to upend professional sports’ ridiculous and reactionary, legalized draft socialism that forced superstars to places they didn’t want to go, greatly restricted their income potential and, oddly enough, reduced the leagues’ own stature by keeping some of its biggest stars in smaller cities. (Everyman fans have little problem with this monstrosity, insisting “They should feel lucky to get paid to play a game.”)

Just a few years earlier, NBA and NFL rules forced Jabbar to Milwaukee (a fine place but not exactly a major, big-league sports city where Jabbar was dying to play) and O.J. Simpson, to that moment college football’s most heralded player ever, to Buffalo. Basketball being kinder on the body than football, Jabbar was able to engineer a trade to L.A. with more than a decade of great years left, while Simpson was hardly seen by most of the country running his knees into the ground, albeit gloriously, in Rich Stadium.

Walton writes that Portland won a coin flip with Philadelphia for his rights in the 1974 draft. His was a negative acceptance; he writes not that he wanted to play there but only that he informed the league he wasn’t going to Philadelphia. He says his contract was “the largest financial deal in the history of all team sports” but that the “only thing” he cared about was to be “in charge of my own personal grooming.”

Before he took the court for the Blazers, the team had ordered up knee surgery. He writes that he came back too soon for preseason games, and then, a month into the season, he couldn’t run because of intense foot pain. “It was late 1974, and things would never be the same again.”

Given the ultimate length of Walton’s career, he is likely the most injured American athlete of all time. Even Joe Namath can’t match it. At UCLA, the knees and tendinitis got attention. Throughout his book, which sounds at times like a guide to Dr. Scholl’s issues, Walton writes repeatedly of the foot problems that annihilated much of his NBA potential.

Despite devastating injuries that wiped out dozens of games and probably dozens of body parts each of his 4 seasons with the Blazers, massive success somehow still found Walton in Portland. For 1976-77, new coach Jack Ramsay put together a workmanlike, overachieving unit anchored not so much by Walton but a young enforcer, Maurice Lucas. They couldn’t top Jabbar’s Lakers for the Pacific Division crown in the regular season but swept them in the Western Conference Finals. Then, the epic Finals, losing the first 2 games to Philadelphia before storming back with MVP Walton for a title they’ll talk about in Oregon forever.

The following season hinted at a repeat. The Blazers were running up a 50-10 record just as Walton began experiencing intense, burning pain and couldn’t play. He writes that team doctors could not determine the problem, “would simply say that I was looking too close and that there was nothing wrong, that I should just go out and play. And that in playing I was not going to make it any worse.”

But struggling to get back on the court as the Blazers faced a big playoff game with the Seattle SuperSonics, he accepted a painkiller from the team doctor. “For the first time in nearly two months, the pain was gone.” But he couldn’t play very well, or even feel the foot for very long, and after the game, the hospital detected a fracture. The Blazers lost the series.

Walton says he has “structural, congenital defects” in his feet, likely nature’s oversight in building this 1-in-a-billion 7-footer. He missed the entire next season. He sued the team doctor (was precluded from suing the team by workers’ compensation laws, he writes) and asked to have his contract terminated. A welcoming landing spot was hometown San Diego, which had just re-entered the pro basketball sphere with the arrival of the former Buffalo Braves, now called the Clippers. While Portland owned legitimate contract interests (based on having the worst record in 1973 and winning a coin flip), here again, Walton found himself on the short end of players’ rights, as the Blazers’ demands for huge compensation and the league-brokered deal ultimately deprived the Clippers of talent.

Injuries so limited Walton’s San Diego tenure — 14 games his first season, then 2 missed seasons — that by 1984, people forgot he was even still in the league. A revolutionary foot operation finally got him back on the court, but the surgeries continued, “every couple of months.” The Clippers moved to Los Angeles for the 1984-85 season but remained an embarrassing franchise. About to give up, Walton writes that he started calling around, that Jerry West “wanted no part of me” but that Boston’s Red Auerbach, surely the game’s greatest executive, was open to bringing him aboard. Again, Walton would force a trade, but this time Auerbach handled the details. Walton’s cost was to sign away his considerable deferred compensation earned with the Clippers. He did, with no regret.

The Boston Celtics boast dozens of unforgettable seasons. Their most memorable is possibly one that includes Bill Walton. Voted NBA’s 6th Man of the Year, Walton played in a career-high 80 games, reinvigorated a championship-level club that would win 67 games, one of the greatest teams in NBA history, swinging the league’s balance of power back from mighty L.A.

It was Walton’s last hurrah as a player. As in Portland, playing time was fleeting. Pain and injuries returned for Walton the next season. He made it into 10 games and told Auerbach he couldn’t do it anymore. The Celtics lost the title to the Lakers and began a decline.

Walton is listed as the lone author of “Back from the Dead.” Given that, it is an impressive writing achievement. There are some things a professional would have done differently. The flash forwards are a bit bouncy but not disruptive. References to newborn children come out of nowhere (one of his 4 sons, Luke, grew to 6-8 and played on NBA championship teams), and obviously Walton had an agreement to leave his first wife, Susie, out of the book, while referring to the couple as “We.” On this level, it’s an incomplete book strictly on the author’s terms.

But there is a powerful if unintentional portrait of a superstar trying to take part in everyday life. College students in the early 1970s protested Vietnam, denounced Nixon, questioned authority, grew long hair, went to concerts, experienced counterculture. Bill Walton did these things unflinchingly. Burnishing his ’70s cred as if it could be any more burnished, Walton surfaced in national media reports in the investigation of Patty Hearst. Readers under 50 will wonder why this is a big deal. But it was. Walton happened to be friends with a couple linked to the Symbionese Liberation Army. “My phones were tapped, my mail intercepted. I was trailed,” Walton writes in a half-page of treatment of this subject.

He was mesmerized by Carlos Santana and Neil Young. But Walton is associated with the Grateful Dead probably more than any non-member, though his accounts in this book are limited to very innocent concertgoing.

Professionally, there were only a few people in the world — Wilt Chamberlain, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Bill Russell — who could relate to Bill Walton, and he writes of them reverentially. On the short list of greatest basketball players are (arrange in the order of your choice) Michael Jordan, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Wilt Chamberlain, Magic Johnson, Oscar Robertson, Kobe Bryant, Bill Russell, LeBron James. There is one big difference between those names and Bill Walton — Walton is white. As a regular human being, Walton is not subjected to prejudice. In conversations about the greatest basketball player, it’s fair to say that perceptions can be tainted by race, including “great white hope” nonsense.

There is something special about the big man of basketball. Other sports can be dominated by “normal”-sized people. Willie Mays was 5-11; Joe Montana 6-2. Basketball can be and is often won by guards, but, as they say, you can’t coach height. The bigs who can play bring immeasurable intimidation and fascination and drama to sport. It was recently estimated that there are maybe 70 people in America under 40 who are 7 feet tall, all of them highly desirable to basketball coaches.

Walton’s presence electrified not only Pauley Pavilion but opposing stadiums. He was not particularly handsome (he resembles the actor Noah Emmerich), but his face bore a California Cool, ultimate confidence, a haircut always threatening to exceed coach’s rules. Courtside in street clothes, he could intimidate opponents just watching them warm up.

Magic Johnson was extraordinary in college but played just 2 seasons and won a title after his team lost 6 games. The closest college performer to Jabbar and Walton is Duke’s Christian Laettner, a remarkable clutch player who just doesn’t have the same numbers, nor was it quite the same to watch.

Walton has never been a coach. That endeavor requires forcing discipline upon others and an ability to push buttons. Walton indicates no such interest.

Nevertheless, it’s disappointing that basketball strategy is well beyond the scope of “Back from the Dead,” because Walton, a very smart man, undoubtedly has scientific opinions on the subject. For example, why do players use the backboard at close range but not from longer range? More importantly: Shouldn’t the offense try to have the same person shoot on every possession? If the defense adjusts to that, then there should be an alternate play to exploit the change. But in general, isn’t UCLA best off if Bill Walton takes every shot? The argument against that may be more emotional than anything else — that everyone wants to shoot, and if a single player takes every shot, other good players needed to win championships won’t want to be on that team, thus a form of socialism prevails.

The greatest transition in sports is Mickey Mantle immediately succeeding Joe DiMaggio in 1951 as the last Yankee king. At UCLA, there was 1 King, and it was Wooden. Elite students would still flock to Harvard if Kingsfield stepped down. That is not the case in college basketball, where UCLA upon Wooden’s retirement completely failed to sustain the extraordinary stature of the program and, within a half-dozen years, fell permanently beneath the likes of North Carolina and Kentucky and later Kansas and Duke and even several others to this day, programs able to win championships with multiple coaches.

Wooden liked to tell the story that upon winning the national title in his final game in 1975, a UCLA booster told him thanks — “It makes up for your letting us down last year.” As heartless, cold and ungracious as this comment is, it reflects the undeniable disaster of UCLA’s 26-4, 1974 season — what should have been the crowning glory of the nation’s most dominant team, ever, instead, one of sport’s great collapses.

Does UCLA adequately appreciate Bill Walton? Wooden re-issued Walton’s No. 32 as soon as he graduated; at least four other players, mostly journeymen, wore it into the late 1980s. Both Walton’s 32 and Jabbar’s 33 were retired in a 1990 ceremony, but Jabbar’s 33 was never given to another player afterwards.

There is considerable debate in the film “Wall Street” about the value of greed. It’s not only a question of “enough” but a troubling zero-sum game. UCLA won 88 straight games but didn’t want to lose. That is not unreasonable, especially for anyone who watched Bill Walton play basketball. Back from the Dead is a jock trying to put into words what requires a lifetime to explain — that the distance between glory and humiliation is as unbelievably thin as those faults in Walton’s feet.

4 stars

(October 2017)

(Updated April 2021)

“Back from the Dead” (2016), by Bill Walton, published by Simon & Schuster