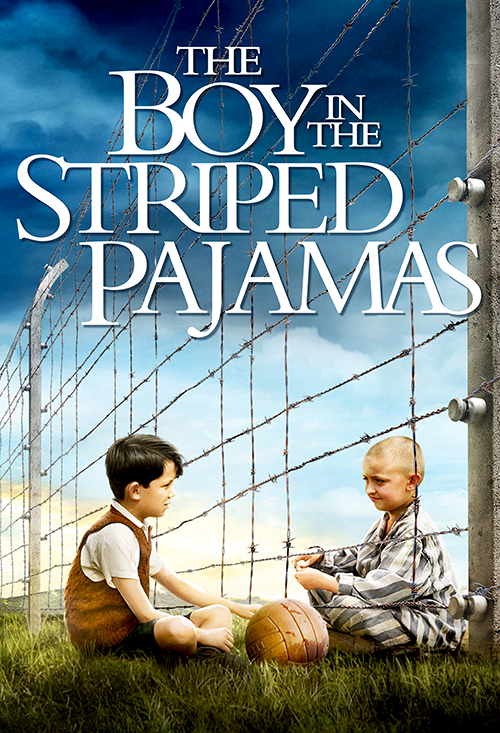

Boy learns why those aren’t

farmers in ‘Striped Pajamas’

Many great films invoke the Holocaust. Each must tell a different element of the story. “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” is about the children, and very young children in fact, 8 years old. There are two reasons it succeeds — it shows the depths of cruelty of a society that would imprison a tiny boy, and it reminds us that human beings are created prejudice-free.

The title says much in so few words. Adults know what the striped pajamas are. A child would not, and would wonder: Who are these people? Why are they farming? Why are they so hungry? Why are they kept inside barbed wire?

Only one person can answer those questions for little Bruno — played by a certain up-and-coming child star, Asa Butterfield — and that is his father, who happens to oversee the camp. His answers — they’re the reason we lost the Great War; they are not real people; — are deplorably absurd, but a curious 8-year-old boy is in no position to agree or disagree, so he must find out for himself.

Is it possible that an outsider, particularly a child, could regularly make contact with a Jew inside a concentration camp? Highly unlikely, though given the extent of the Holocaust, it probably happened somewhere. In “Pajamas” we are told it is possible, and we can take the drama from there. Certainly if an 8-year-old could roam about undetected in the woods and dig underneath fences, adults could figure this out as well. Most films dealing with incarceration raise the specter of possible escape. This one does so only in the slightest. “Pajamas” is not about escapism. It wants to take us right to the edge of the camp, our minds a clean slate, to witness and interpret what is happening.

And what is it we see: An 8-year-old boy pushing around a wheelbarrow that is way too heavy for him, teeth rotting, starving, but forced to produce abundant food for the warden’s family to enjoy.

Child stars, such as Haley Joel Osment or Lindsay Lohan, are generally given a stage of their own, surrounded by adults. Here, Butterfield’s impressive work might actually be upstaged by 10-year-old Jack Scanlon. His Shmuel is not as demanding, but he plays it remarkably steady and reserved, a hungry 8-year-old going on 80 in terms of what he knows of human nature.

British director Mark Herman, with a handful of credits, succeeds with the suspense, but sacrifices drama for plot’s sake. As the Jews gradually enter Bruno’s life, both the excitement and fear multiply — perhaps there is something he can do for them, but there is risk to all parties involved if he is caught assisting them.

His father is an intellectual fraud, a thug in a suit, whose own mother regrets what he has become. The boy’s mother is much more sympathetic, but not completely so — this is a woman who evidently enjoyed the family’s status as S.S. luminaries as long as she could ignore what was going on.

Bruno’s sister, Gretel, is a tragic figure. This is a 12-year-old girl who in her room would not have posters of David Cassidy, but Der Fuhrer. She is a pretty, sweet girl who must be capable of knowing better, but has fallen for her father’s spiel, probably because the most impressive men in her world are the ones in Gestapo uniforms. Were she a bit younger, she could probably change, but she is old enough to be interested in young men, and so her brainwashing is likely complete. We can expect, given the family’s status, that she would survive the war’s end and at worst, spend the rest of her life condemning Jews for defeat in the war and her family’s loss, or at best, living in horror at the level of evil she and her family embraced. She and Bruno present excellent character bookends: One of them is just beginning to learn about the world; the other has already made up her mind.

One of the most disturbing elements of “Pajamas” is the timing, something it shares with another recent film about Nazi Germany, “Downfall.” Both take place at the end of the Third Reich, when Allied bombs are smashing Berlin. Maybe the war will end in time for a boy like Shmuel to be saved. If he is not saved, is it more tragic if he dies in 1945 than 1942? Clearly Herman does not think so — the small bits of Nazi Germany we see look healthy, wealthy and strong; there is no suggestion that if Patton can only get there a little faster, the people in Shmuel’s camp will be OK.

Herman, inadvertently it seems, raises troubling questions about education. The children are tutored by an esteemed older man who has all the appearances of being wise. Yet they should not believe him, of course, but one of them does, without hesitation. Should children challenge what they are taught? A child from the South and a child from the North might have differing reactions to what they read in the same Civil War textbook. And what, if anything, might they be taught today with our approval that 70 years from now would haunt us at the cinema?

A Holocaust film such as “Pajamas,” however well done, hammers with frustration. This is madness. This was only seven decades ago. In coming years, decades, we will see more pictures about World War II-era Deutschland, and the Nazis will never change. The saddest, most gripping images in “Pajamas” are not of the boys, but the propaganda films of young Jews purportedly “enjoying” their time in the camps: horrifying, profoundly sad and, in this movie and others, somehow remarkably watchable.

Surely there were books, theater productions and even films at those times depicting the evils of tyranny and prejudice and genocide, but in 1930s Europe, they didn’t sway enough minds. Has the world always been this way? Is madness inevitable? Why does this subject matter attract theatergoers and extensive critical praise ... is it really because we need to know what happened many times over and appreciate being retold, or because we find it so fascinating? Maybe an excellent, well-meaning film such as “Pajamas” should be condemned — for exploiting the kind of drama that never should’ve existed in our world, but we all know did.

3.5 stars

(November 2008)

“The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” (2008)

Starring Asa Butterfield as Bruno ♦ Jack Scanlon as Shmuel ♦ David Thewlis as Father ♦ Vera Farmiga as Mother ♦ Amber Beattie as Gretel ♦ Vera Farmiga as Mother ♦ Zac Mattoon O'Brien as Leon ♦ Domonkos Németh as Martin ♦ Henry Kingsmill as Karl ♦ Cara Horgan as Maria ♦ Zsuzsa Holl as Berlin Cook ♦ László Áron as Lars ♦ Richard Johnson as Grandpa ♦ Sheila Hancock as Grandma ♦ Iván Verebély as Meinberg ♦ Béla Fesztbaum as Schultz ♦ Attila Egyed as Heinz ♦ Rupert Friend as Lieutenant Kotler ♦ David Hayman as Pavel - Jewish servant ♦ Jim Norton as Herr Liszt ♦ László Nádasi as Isaak ♦ László Quitt as Kapo #1 ♦ Mihály Szabados as Kapo #2 ♦ Zsolt Sáfár Kovács as Kapo #3 Sonderkommando ♦ Gábor Harsay as Elderly Jewish Man

Directed by: Mark Herman

Written by: Mark Herman

Written by: John Boyne (novel)

Producer: David Heyman

Co-producer: Rosie Alison

Co-producer: Péter Miskolczi

Co-producer: Gábor Váradi

Line producer: Mary Richards

Executive producer: Mark Herman

Original music: James Horner

Cinematography: Benoît Delhomme

Editing: Michael Ellis

Casting: Leo Davis ♦ Pippa Hall

Production design: Martin Childs

Art direction: Rod McLean ♦ Mónika Esztán ♦ Razvan Radu ♦ Szilvia Ritter

Set decoration: Gábor Nagy

Costume design: Natalie Ward

Makeup and hair: Marese Langan ♦ Hildegard Haide