‘Falcon’ a bit lacking in stuff

legendary films are made of

Is the falcon really fake?

In a movie where virtually nothing is believable, some are going to wonder whether Sam Spade inadvertently left a quarter of a million dollars — or more — in the hands of the San Francisco Police Department.

Surely, the statue can’t be real. If it was, it would legitimize the immense amount of chicanery and skulduggery of the people in “The Maltese Falcon,” a movie in which nothing is really what it purports to be and most of the characters are buffoons.

Start with the title, for it is a grand one. An exotic Mediterranean location coupled with a fearsome, impressive raptor. It would make sense that a European king somewhere once demanded a gold- and jewel-encrusted statue of such a bird from such a place. One could envision Errol Flynn dispatched by Elizabeth I in “The Sea Hawk” to find it once he has defeated the Spanish Armada...

... Yet we have a movie that takes place not in the exotic locales of, say, “Raiders of the Lost Ark” ... but in various apartments, hotel rooms and bare-bones offices of a U.S. city.

By about halfway through, it’s fairly clear, these people aren’t going anywhere, and they’re not going to stumble onto any priceless bird here.

The irony is dripping from the opening scene, in which virtually every comment is bogus. An attractive woman, played by Mary Astor, tells Sam Spade, “I’m trying to find my sister.” She asks him to somehow retrieve this sister during a lengthy story that is virtually unintelligible. Sam eventually restates her request and says that even if they have trouble returning this adult woman to New York, “well, we have ways of managing that.”

Meanwhile, Sam’s partner has entered the office and also conversed with their new client. After she leaves, he expresses a social interest in her. Sam tells him, “You’ve got brains ... yes you have,” and he says it with just the tiniest trace of a taunt that we know he’s really saying just the opposite.

That opening scene is similar to one of the first scenes in another famous noir, “Chinatown,” which is also reviewed on this site. A mysterious woman shows up at a private eye’s office and tells a lie, but the P.I. takes her money and accepts the job anyway. Jake Gittes is soundly duped. Sam Spade, on the other hand, is always ahead of the curve, and able to smirk about it.

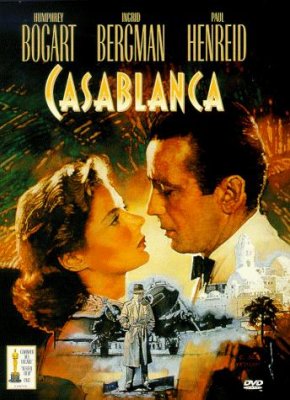

Humphrey Bogart, as Spade, is playing his typical role seen in other legendary films such as “Casablanca,” also reviewed on this site. He’s the ultimate law-abiding mercenary, but even while he’s in it for himself, he has a heart. “I stick my neck out for nobody,” he says, or might’ve said; seems like we heard that in “Casablanca.” He does, however, uncork one of history’s most famous lines in “Falcon,” one you’ve heard dozens of times, a line that has been twisted into something a lot more inspirational than its original meaning.

His challenge here is to provide enough motivation for Spade to get to the bottom of a caper he is visibly mocking. Clearly, like J.J. Gittes, he enjoys the nuances of detective work, outfoxing authorities, maybe roughing up a bad guy here and there. But for most of the movie, he is more caught up in the events around him than he is interested in figuring things out. Several people offer to pay him money, or do pay him money, or sort of pay him money, but to do what, we’re not always sure. Is this project a business bonanza? Doesn’t seem like it. We don’t even really know how these people stumbled into his office in the first place.

Of course the falcon is a red herring; the plot driver is a pair of murders. But there’s a flaw in that only one is shown, only barely. The other occurs offscreen, involving a character we never see.

Spade doesn’t seem too broken up about the death of his partner. That’s partly because he’s been having an affair with the man’s wife. In a classic line, after kissing the “grieving” woman behind a closed door, his secretary asks, “Well, how did you and the widow make out?” He later makes the point the man had no kids and a wife who didn’t want him around anymore.

There could be incentive to solve the mysteries to end the police scrutiny. After all, he appears to be a suspect in at least one murder. But he is highly confident in his protestations, and the cops have no choice but to believe him. He’s not afraid of getting arrested and has nothing to prove.

So motivation is a problem, but we have to live with it. Spade is just having fun on the job. He grins whenever he succeeds in duping his adversaries or the police. He seems a lot more inclined than his audience might be to listen to all of the characters’ stories. There is risk that viewers will quickly tune out some of the monologues. Do they need to absorb them? No, not really, because in exchange for watching, they get Bogie in one of cinema’s most classic poses, standing there, or sitting there, impeccable suit, usually a hat, staring at his subjects with either skepticism, alarm or mockery.

Enough unexpected events occur to keep the plot necessarily unpredictable, but the glorious John Huston, in his directorial debut (the 1929 novel by Dashiell Hammett was a big hit; the 1931 original pre-code “Falcon” film would be superseded by this one), falls prey to cliche. He opens the film with a completely unnecessary text passage on the history of the falcon, which is more or less repeated by one of the characters later in the movie. Way, way too many guns are drawn or taken away and not fired. A character is served a drink that is spiked.

This is noir that flirts with being a farce. But this is Bogart and Huston, and they can pull it off. Huston secures the ending with the depiction of the statue. It is no small consequence what the bird looks like. If it looks ridiculous, too big or too small, we have a farce. But it looks real. It’s plausible that somewhere around Istanbul is a Russian officer with the real thing, and it’s worth a fortune, and that someone would go to great lengths to swipe it. This bungling crime ring certainly wasn’t capable of stealing something so valuable. As the ringleader, Sydney Greenstreet, in his first movie, is inept on every level. He sells out his favored henchman, saying the man is like a son, but “there’s only one Maltese Falcon.” He recklessly slashes at the statue, believing (apparently correctly) that he can deduce in seconds whether it is real and unconcerned that if it is real, he is severely damaging it.

Finally we learn why Spade couldn’t let this frivolous caper go. It could’ve been romance, but it’s really professional courtesy. “When a man’s partner is killed, you’re supposed to do something about it,” he says, albeit not terribly convincingly. It’s “bad business” to let the killer get away with it. Would he have really pocketed a six-figure sum from the bad guys if the falcon was real? No, it seems like he was in it for the justice all along. And for the opportunity to deliver one of cinema’s most famous lines, about the falcon: “It’s the stuff that dreams are made of.”

“The Maltese Falcon” is early noir, and vintage Bogie. But it’s probably been accorded far more acclaim than it deserves. In 2007 it ranked 31st on the American Film Institute’s all-time list. Its place is debatable. Oddly enough, so is its pronunciation. Few words split Americans like “falcon.” (Maybe “route,” but that’s the only other one that comes to mind.) Is it really pronounced “phal-kin,” or “fawl-kun”? The public can agree to disagree on that one. On Bogart, it’s unanimous.

3.5 stars

(October 2008)

“The Maltese Falcon” (1941)

Starring Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade ♦ Mary Astor as Brigid O’Shaughnessy ♦ Gladys George as Iva Archer ♦ Peter Lorre as Joel Cairo ♦ Barton MacLane as Det. Lt. Dundy ♦ Lee Patrick as Effie Perine ♦ Sydney Greenstreet as Kasper Gutman ♦ Ward Bond as Det. Tom Polhaus ♦ Jerome Cowan as Miles Archer ♦ Elisha Cook Jr. as Wilmer Cook ♦ James Burke as Luke ♦ Murray Alper as Frank Richman ♦ John Hamilton as District Attorney Bryan ♦ William Hopper as Reporter ♦ Walter Huston as Capt. Jacobi

Directed by: John Huston

Written by: John Huston

Written by: Dashiell Hammett (book)

Executive producer: Hal B. Wallis

Associate producer: Henry Blanke

Original music: Adolph Deutsch

Cinematography: Arthur Edeson

Editing: Thomas Richards

Art direction: Robert Haas

Costume design: Orry-Kelly

Makeup: Perc Westmore, Frank McCoy