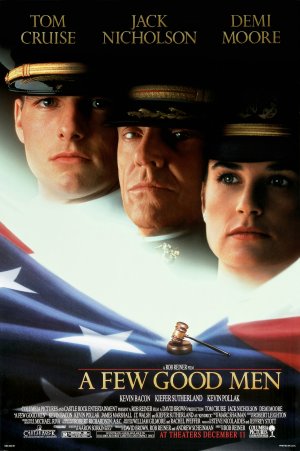

‘A Few Good Men’ picks up

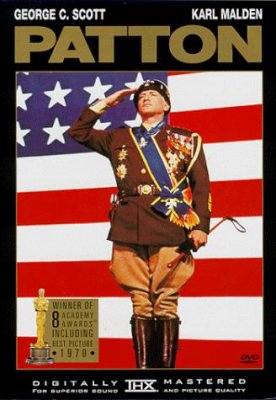

where ‘Patton’ left off

Surely at the end of “A Few Good Men,” there’s a date in store for Danny and Jo.

That it didn’t happen during the film is a testament to the suspense capabilities of Aaron Sorkin and Rob Reiner, who only managed to convince you there’s a romance here for as long as they needed to.

“A Few Good Men” is quite possibly, with the possible exception of “Urban Cowboy,” the most chauvinist popular mainstream American film since the 1970s — starting with its title. Doesn’t Jo get any credit? No, and not even a date.

Not a problem. Web searches do not indicate the National Organization for Women ever protested the film. Roger Ebert, in his original 1992 review, makes no mention of sexism, notes the lack of mutual attraction and says a friend told him Jo was “originally conceived of as a man, and got changed into a woman for Broadway and Hollywood box office reasons, without ever quite being rewritten into a woman.”

The goal of the film is to get Tom Cruise’s underachieving Daniel Kaffee to finally realize what a great lawyer he is and start serving society at a much higher level. Typically, a character such as Demi Moore’s Jo would be something of a Princess Leia-esque equal. Instead she is merely another button-pusher for Danny, a woman who makes him a better man. She’s the lone figure to whom incompetence is assigned. Jo gets walked over by the males (superiors and subordinates alike) in the Navy legal department, has so poorly prepped her own client for trial that by any analysis she should be removed as counsel, bungles her team’s first big courtroom score by “strenuously” objecting, and even has to ask Danny out for dinner, not the other way around.

Is she actually good at anything? Well, yes. She has instinct. She senses right away there’s something stinky about this case, and she correctly realizes Danny is the right person to lead the defense. She’s relentless and doesn’t quit. There’s an ideal job for her somewhere, it’s just not in the Navy or in this movie.

While the goal is getting Danny to find himself, the film’s message is an unmistakable acceleration of “Patton”: Old-school military is no longer any good. Jessep pays for being a dinosaur. He underestimates the potential of a woman, who is capable of defeating him. Instead of protecting his troops, his tactics harm them. He promotes and relies on a man he knows to be of inferior character, Kendrick, because Kendrick serves his anti-enlightenment agenda. The modern military needs people like Jo, not people like Jessep.

Sorkin struggles mightily with Jessep’s motivation. Is this one of history’s greatest villains ... or a sympathetic fall guy. What really is Jessep’s problem? He’s got a chip on his shoulder. He feels underappreciated. But why? He explains early that he’s been promoted faster than his rival Markinson (one of several examples of the film’s résumé-reciting that is so out of control, the script even has Kaffee make fun of it later). It’s made abundantly clear he’s heading to a premium position at the National Security Council. He’s not running an unpopular war, but safeguarding a base in peacetime. In Jessep’s case, the system clearly works. Why is he so adamant about disrespect?

Consider what must’ve been Jessep’s emotions during his testimony. He ordered an event that caused the death of one of his Marines. Certainly he believes an early statement he makes to the court, that Santiago’s death, “while tragic,” probably saved lives. Does he really believe Dawson and Downey poisoned the rag? Probably not. Would he want them to spend time in jail and be dishonored? He can make flights disappear, but he’s unable to arrange anything better than six months and a dishonorable discharge for Dawson and Downey. This is where the script lacks richness. We’re to believe Jessep comes unglued only over Kaffee’s snarkiness, when there could, and probably should, be a much deeper reason — the torment of watching troops under his command punished for carrying out his orders.

One reason “A Few Good Men” remains remarkably watchable two decades later is that the errors and shortcomings almost seem more like the work of genius. It should be standard that Danny and Jo must become a social team, but the infinite dangling of that treat only heightens the drama. The victim’s family is not only not demanding justice, but inexplicably AWOL from the film, clearing the way for capable Kevin Pollak to play the skeptic and sparing us any regrets from celebrating Danny’s triumph. Three or four soulless conversations are devoted to a person never seen in the film, Danny’s father. Yet the dialogue in those exchanges, delivered by Jack Nicholson and Pollak, is so amusingly self-aware, it’s as if the characters know they are discussing a fictional person and letting everyone else in on the joke.

Ebert’s beef is that Danny, when discussing his final courtroom strategy with his associates, telegraphs the climactic scene that should not be telegraphed. Ebert has a point. It’s superseded by the cleverness of how Danny gets to that historic moment, with one of the greatest questions of logic ever posed in a movie, and one you didn’t see coming: “If your orders are always followed, then why would ...”

Sorkin, who wrote the screenplay, became well-known for TV’s “The West Wing,” which snapped through White House drama at breakneck pace. Sorkin’s propensity to deliver a line in “A Few Good Men” is off the charts; pretty much every character slings the b.s. in every scene, leading up to “You can’t handle the truth,” the most famous movie line of the last 20 years, more famous even than “Show me the money” from a later Tom Cruise film.

In fact the “truth” quote overshadows a lot of other moments of great dialogue. Turn it on TV at any moment, you get a zinger. “Possession of a condiment ... We really need the practice ... Wear matching socks. Good tip. ... Strenuously object ... The entire time you’ve been at Gitmo you’ve never had a meal? ... I was expecting someone older. So was I ... There is nothing on this earth sexier, believe me gentlemen, than a woman you have to salute in the morning. ... You don’t even know me. Ordinarily it takes someone hours to discover I’m not fit to handle a defense. ... Don’t look now Danny, you’re making an argument. Huh? Oh yeah ...”

Are there some clunkers? Yes, such as Danny’s “steak knives” tirade, his flat “sexually aroused” comeback to an early spiel from Jo, Jessep’s ridiculous “surrendering our position” gag, and the potentially effective scene of Kaffee’s bewilderment of actual real-life law marred by the screenwriter’s need to somehow include “a courtroom” rather than “it” in Danny’s reflection, “So this is what a courtroom looks like.” The movie occasionally will underestimate your intelligence (why we need words on the screen early to tell us we’re at Guantanamo and Washington, who knows), which may partly explain why the final courtroom questioning is so effective.

Jack Nicholson at the 1993 Oscars.

Sorkin has told of how the inspiration for the play and film came from his sister Deborah, who was assigned a similar case in the Navy’s Judge Advocate General Corps. Sorkin says he was bartending at the time, and upon hearing that his sister was headed to Guantanamo, began writing the script on a cocktail napkin.

“A Few Good Men” would almost have the feel of a classic noir if it weren’t so sunny and ’90s-ish. Consider where the crime occurs.

In the early ’90s, and to this day, the Korean DMZ would be an ideal location for Jessep’s unit. It’s peacetime, but a threat very much exists on the other side of the wall. A fence-line shooting would be a very serious international incident.

But that would add at least a small amount of legitimacy to Jessep’s Patton-esque argument and clearly was not the direction a filmmaker such as Rob Reiner saw the country heading in 1992. So we have shiny and warm Cuba, where officers are even made to look ridiculous trying to camouflage themselves from the “grave” danger of Cuban soldiers who are deemed so threatening by the script, they are never depicted in the film.

From the beginning we have characters slowly learning about events that occurred offscreen before the film ever started, or just very shortly thereafter. There must have been a fascinating discussion in the editing room as to whether the scene of Jessep, Markinson and Kendrick arguing should go out of sequence. Reiner evidently decides this backstory needs context and can’t be shown chronologically, which would be first. Or, he’s just compelled to lead with the homicide. Is the Jessep confab really needed? By the time Danny and Jo have conversed with the colonel and Kendrick over lunch, we know that Jessep has lied, which makes things simple but also eschews what might’ve been a more fascinating whodunit. Of course Kaffee doesn’t exist for that, but to realize his potential.

The process of the defense team’s discovery isn’t nearly sexy enough; a huge roadblock exists in the dim-wittedness of the two defendants, who for strange reasons seem content to be wrongly convicted and spend decades in jail. They volunteer virtually no information that might help their cause. Incredibly, we ultimately find that the most clueless defendant has so poorly informed his attorneys of what he actually did that the entire defense is dealt a massive, embarrassing setback at a critical moment. (That Downey, and not Dawson, is the one testifying defies reason; the script needs one of them on the stand to provide a setback and Dawson apparently would be above that, so this angle can be implicitly written off as an example of Jo’s incompetence.)

Because the case proceeds at ridiculous lightning pace, we learn virtually nothing about our victim, Santiago. He is not physically up to the job. However, he is much less concerned about that than reporting his fellow Marines to the highest authorities. What kind of audacity is this? Apparently he is angry at being shunned at the mess hall. He’s desperate to get out. So he accuses his lone defender, Dawson, of a serious transgression in a manner that will clearly make Santiago a pariah not just on his base but in the entire Marine Corps.

How often do fence-line shootings happen, and are they a big deal? Chances are, that’s classified. Either one of two things is true: Dawson is so reckless that he’s the one who endangered the Corps and should be out, or Santiago has gone to such great lengths to cause trouble that many people probably would think a code red is in order.

“The West Wing,” as well as the recent hit “The Social Network,” is ample proof of Sorkin’s prodigious ability to write fast-paced stories. “Men” never feels boring. Where he struggles in this picture is the backstory, an inability or unwillingness to show why characters are the way they are, but reducing most of the emotion and motivation to soundbites and endless résumés. They are not “thin” characters, just incomplete.

His premise is sound — an underachiever who realizes his potential. But Sorkin is never totally sure why Danny is an underachiever.

A lot of films, such as Paul Newman’s “The Verdict,” would suggest substance abuse. Sorkin opts for something along the lines of Han Solo, completely functional and highly competent at what he does, only at the lowest-common-denominator level.

Kaffee, we’re led to believe, has wilted beneath his unseen father’s success. Reiner, though, is unwilling to show either Pops or a young Danny in flashback. Obviously Dad made it big, Junior feels like he’ll never measure up, and so Junior is taking life’s path of least resistance, the lawyer equivalent of clock-punching despite occasionally flashing remarkable instinct. Why is Danny so unambitious? Every time Sorkin tries to tell us, it fizzles.

One thing Reiner is crystal-clear about is that there will be no racial overtones in this film. Dawson, the superior of the two Marines charged, is African-American. So is J.A. Preston’s impressive judge Randolph. An African-American woman is seen at Kaffee’s morning assignment meeting, and African Americans constitute much of the jury box. All of that, refreshingly, would escape notice nowadays as routine, except that Reiner remarkably feels it necessary to tell viewers twice, clumsily, that Danny is not a bigot, presumably because the script requires Danny to hector Dawson. One of those moments involves a scene of Danny joking with the newsstand operator, who is black, unnecessarily used to foreshadow Markinson’s later arrival at the same location. The other moment is when Jessep recites Lionel Kaffee’s résumé as a civil rights defender to Kendrick, a curious implication that Kendrick in fact might be bigoted, which does not seem to be a notion the rest of the film is willing to accept even though the deceased is Hispanic and Kendrick admits to punishing Dawson, for being a samaritan and not following an order.

For the hero, Sorkin interestingly takes the opposite approach of “Top Gun,” the blockbuster that catapulted Cruise to megastardom about six years previous. Many dismiss that picture as a special-effects/beefcake celebration light on useful drama, but in fact there is solid conventional footing, a hotshot military underachiever who makes mistakes because he is trying to outperform his late father. Where Maverick Mitchell needs to rein in the discipline, Daniel Kaffee needs to let it go, finally see what he can do.

Cruise, Sorkin and Reiner are in lockstep at revealing Danny’s potential. Consider how Cruise spins one potentially tiresome scene into a moment of greatness. Danny, with Weinberg, meets Jo for the first time, and after expressing the usual male insolence toward Jo’s rank, very credibly displays little grasp of the importance of the case or Navy hierarchy in general. Out of nowhere, Danny asks a couple quick questions, including, “Am I correct to assume that these letters don’t paint a flattering picture of Marine Corps life at Guantanamo Bay?” and in a moment has a plea and 12-year sentence figured out, concluding with “Pretty impressive, huh,” a sign of his brilliance and underachievement all in one tremendously effective moment.

Perhaps the most valid complaint about Cruise’s performance — aside from a few bits of likely intentional overacting such as in the “galactically stupid” rant — is that he is simply too good as a courtroom attorney. This brings to mind the staggering turn in “Friday Night Lights” of Billy Bob Thornton, who is so good you’re inclined to think he’s running an NFL team.

Cruise is so effective in court from Day 1, and so unflappable as the case progresses, he actually makes lawyering look way too easy. This is supposedly a newcomer at trial law. Yet he never makes a mistake. Why is this newcomer to a courtroom instructing his seasoned colleague Sam Weinberg before the trial starts to never look surprised? Kaffee makes all the right calls from the defense table, always uses the right tone, does not appear frustrated and requires no help from his more seasoned (at least in the case of Weinberg) colleagues. One wonders how easy this case would’ve been for him if his defendants merely had a clue and if Markinson wasn’t racked by guilt.

One of the strongest images a director can produce is the look of respect from an adversary. Perhaps the best ever is Carl Weathers’ painful sigh when he sees Rocky Balboa rise in the 14th round. While not nearly as dramatic, Reiner delivers with Kevin Bacon’s expression after Kaffee has made a neat little counterpoint about directions to the mess hall in the Marine Corps handbook. Unfortunately, given the strengths Danny has already exhibited in court, this is almost anticlimactic and would carry greater significance if it came from the judge, or perhaps even Jessep, though the chosen, unyielding temperament for Jessep seems correct.

One thing that isn’t going to derail Danny’s rise is romance. If the script had a deeper story, one might suspect that Reiner is trying to tell us something about Danny. No sign of any girlfriends, no interest in Jo, and a home whose decor doesn’t quite suggest swingin’ bachelor pad.

The script, though, plays it straight, and in the end there’s no reason to think Danny doesn’t either. Reiner is almost oddly defiant about romance. Jo isn’t really interested, and neither is Danny. Reiner uses a remarkably sexist Jessep comment in Guantanamo to suggest Danny and Jo will ultimately be partners in more than just a legal case, but his chauvinism is quickly ignored. There are two or three moments as a viewer when one senses, “OK, here’s the breakthrough where Jo helps Danny out and he sweeps her away,” but it never happens. By the end, it’s no longer relevant. Jo can reset her career priorities, and Danny can think about the big leagues.

For all of his flourish, Cruise, as is typical, was ignored by the Oscars. Best leading actor nominees included Al Pacino (winner, “Scent of a Woman”), Clint Eastwood, Denzel Washington and Robert Downey Jr. Nicholson received a supporting nomination; in a year packed with legends, he lost to Gene Hackman from “Unforgiven.” “A Few Good Men” collected four nominations, including ones for sound and editing, but won none. Its greatest endorsement is the best picture nomination, back in the day when there were only five.

Is Jessep really in big trouble? He’s not going to get the NSC gig, but most likely a man able to make flights disappear will receive enough establishment support to avoid much more than a reprimand. Retirement is imminent. Notice the ending avoids any characterization of what the actual order was. He and Kendrick can say they never ordered a rag in the mouth. The doctor, as Danny indicates, will ultimately have a lot to answer for. Santiago’s death will be pinned more on medical incompetence than hazing gone awry, and his invisible family will receive a settlement. Despite the verdicts in the film, Dawson and Downey are realistically likely on the hook for some kind of involuntary manslaughter, if in the form of a civil suit.

Where is Danny going? He’s apolitical, and the military seems too formal and unforgiving, so just as Jo suggests, he’ll probably end up a celebrated trial lawyer at some elite New York or L.A. firm. But he doesn’t seem highly motivated by money, and a lofty position would be certain to cut into his softball time. By the end we’re never really sure if he actually believed in his clients, or just their case.

The toughest critics will acknowledge the great work of Cruise-Nicholson but dismiss this picture like one of Kaffee’s plea bargains. That’s fair, but an injustice. Sorkin and Reiner haven’t put together so much a great movie, but the greatest episode of “Law & Order” ever produced.

4 stars

(February 2011)

“A Few Good Men” (1992)

Starring Tom Cruise as Lt. Daniel Kaffee ♦ Jack Nicholson as Col. Nathan R. Jessep ♦ Demi Moore as Lt. Cdr. JoAnne Galloway ♦ Kevin Bacon as Capt. Jack Ross ♦ Kiefer Sutherland as Lt. Jonathan Kendrick ♦ Kevin Pollak as Lt. Sam Weinberg ♦ James Marshall as Pfc. Louden Downey ♦ J.T. Walsh as Lt. Col. Matthew Andrew Markinson ♦ Christopher Guest as Dr. Stone ♦ J.A. Preston as Judge Julius Alexander Randolph ♦ Matt Craven as Lt. Dave Spradling ♦ Wolfgang Bodison as Lance Cpl. Harold W. Dawson ♦ Xander Berkeley as Capt. Whitaker ♦ John M. Jackson as Capt. West ♦ Noah Wyle as Cpl. Jeffrey Barnes ♦ Cuba Gooding Jr. as Cpl. Carl Hammaker ♦ Lawrence Lowe as Bailiff ♦ Josh Malina as Tom ♦ Oscar Jordan as Steward ♦ John M. Mathews as Guard #1 ♦ Aaron Sorkin as Man in Bar ♦ Al Wexo as Guard #2 ♦ Frank Cavestani as Agent #1 ♦ Jan Munroe as Jury Foreman ♦ Ron Ostrow as M.P. ♦ Matthew Saks as David ♦ Harry Caesar as Luther ♦ Michael DeLorenzo as Pfc. William T. Santiago ♦ Geoffrey Nauffts as Lt. Sherby ♦ Arthur Senzy as Robert C. McGuire ♦ Cameron Thor as Cdr. Lawrence ♦ David Bowe as Cdr. Gibbs ♦ Gene Whittington as Mr. Dawson ♦ Maud Winchester as Aunt Ginny Miller ♦ Bernard Madrid as Interrogator (uncredited per IMDB)

Directed by: Rob Reiner

Written by: Aaron Sorkin

Producer: David Brown

Producer: Rob Reiner

Producer: Andrew Scheinman

Co-producer: Steve Nicolaides

Co-producer: Jeffrey Stott

Executive producer: William Gilmore

Executive producer: Rachel Pfeffer

Original music: Marc Shaiman

Cinematography: Robert Richardson

Editing: Robert Leighton, Steve Nevius

Casting: Janet Hirshenson, Jane Jenkins

Production design: J. Michael Riva

Art direction: David Klassen

Set decoration: Michael Taylor

Costume design: Gloria Gresham

Post-production supervisor: Christy Dimmig

Production manager: Steve Nicolaides

Makeup and hair: Steve Abrums, Larry Waggoner, Sherri Bramlett, Enzo Angileri, Lyndell Quiyou, Richard Dean, Edouard F. Henriques III

Stunts: Tim A. Davison

Special thanks: John Horton

Special thanks: Major Michael McClosky

Special thanks: Ray Smith

Thanks: Walter L. Hill II

Thanks: Robert A. Washington

Thanks: Haskell Wexler