Shouldn’t Ray Kinsella have questioned why his ‘Field of Dreams’ hero is batting right-handed?

Shoeless Joe Jackson, at least the “Field of Dreams” version, has to be one of the strangest movie characters. A zombie. Emotionless. Eyes from “The Terminator.” Inhabiting some pre-heaven way station, not knowing where he is or what he’s doing or why, not quite matching the real person, but aware that he has died. A broker/translator, between the other zombies and the people whose yard they’re playing in. “I guess I’m real,” he reveals early in the film. Somehow in peak physical shape and perhaps more clean-cut than he ever was during his life.

But perhaps the most curious description of Joe Jackson in this film is that of hero. He is a very interesting choice for baseball victimhood over the likes of, say, Clemente or Gehrig, or Negro Leagues players who never had a shot at MLB. (All of the players who turn up on the field are indeed white, even though at least one of them, Gil Hodges, played post-Jackie Robinson.) We are told that Jackson got screwed, that apparently it was a misunderstanding, that he sorta was involved in the plot but didn’t actually try to lose games. Joe says being “thrown out” of the game felt like part of himself was “amputated,” although he did actually keep playing baseball for a long time, outside of the big leagues, so it’s unclear why he would need to play in Iowa for free ... and not even in real games, but what appears to be practice sessions ... but Jackson’s presence is just a slice of the quirky Redemption Tour taking place in Ray Kinsella’s Iowa cornfield that apparently can and does mean anything to anyone.

Roger Ebert thought it worked. In a four-star review in 1989, he observes, “The movie sensibly never tries to make the slightest explanation for the strange events that happen after the diamond is constructed.” Actually, that’s not exactly true. We see four stories unfold of adults — all males — realizing an opportunity to erase some of the regrets of their youth. All they have to do is heed the messages they’re getting from this mysterious voice.

“Field of Dreams” is further affirmation that our admiration for sports heroes is based almost entirely on their athletic production. There are numerous humanitarians who batted .254 whom you’ve never heard of. Players who have troubles inspire defenders by the quality of their stats, not their character. Ray Kinsella mulls how his field can “right an old wrong.” He recites Jackson’s stats as proof that Jackson got a raw deal. This movie gently says Jackson and the others were “suspended,” for life — a more accurate term is “banned,” but the filmmakers evidently found that too strong for their unusual hero.

Regret is a powerful emotion all humans share on some level. Some movies, particularly when a character turns against a bad guy, depict it well. One major setback of “Dreams” though is that none of the regrets are really visual. It takes endless speeches/interviews to learn what’s bugging these people. Bios are read constantly. Endings for each character are explained not particularly convincingly.

The speeches start right from the beginning, as the offscreen protagonist describes not himself, at first, but his father, and supplies too many details to absorb (such as, how Dad rooted for more than one team). Before we’ve even met our hero, he’s telling us about someone else in a description that surely could’ve waited for the van ride. The intro is done this way to establish an end point, that Dad figures prominently in this person’s life, and that’s where the story will culminate. This intro otherwise could’ve been saved for later in the movie, or could’ve been performed as a scene or two of the actors at a young age having some kind of disagreement.

One of the many curious shortcomings of this movie that should’ve seemed obvious to the filmmakers — and maybe those shortcomings were obvious but deemed inconsequential — is that the hero character is given no problem. His life is going along the way it’s been going along for years, family’s OK, they’re attractive people with an attractive homestead; nobody’s dying or broke. Ray will reveal one night, “I’m scared to death I’m turning into my father.” This is a problem, Ray claims, because “The man never did one spontaneous thing in all the years I knew him.” So we have a man (Ray) undergoing a fairly common mid-life “crisis,” which is fears that he may have the same (what he believes is an) unsatisfying life as his father. The mystical intrusion on his life happens immediately. Most movie plots would give Ray Kinsella some kind of incentive for heeding the voice.

Ray Kinsella has a few things in common with Eddie Albert’s Oliver Wendell Douglas of “Green Acres.” But Ray seems more like Steven Keaton, the 1980s TV dad of “Family Ties” whose hippie-like idealism of the ’60s had been very much softened by parenthood and the onset of the 1980s or suburban life. Series punch lines revolved around the kids’ eye-rolling at the parents’ nostalgia. The Iowa of “Dreams” is portrayed as a reactionary place that could use a jolt of inspiration from this former New Yorker. But “Dreams” falls victim, as do other movies such as “Save the Tiger,” of throwing in a kitchen sink of pop culture musings that mattered to the author but don’t seem to have any connection with each other.

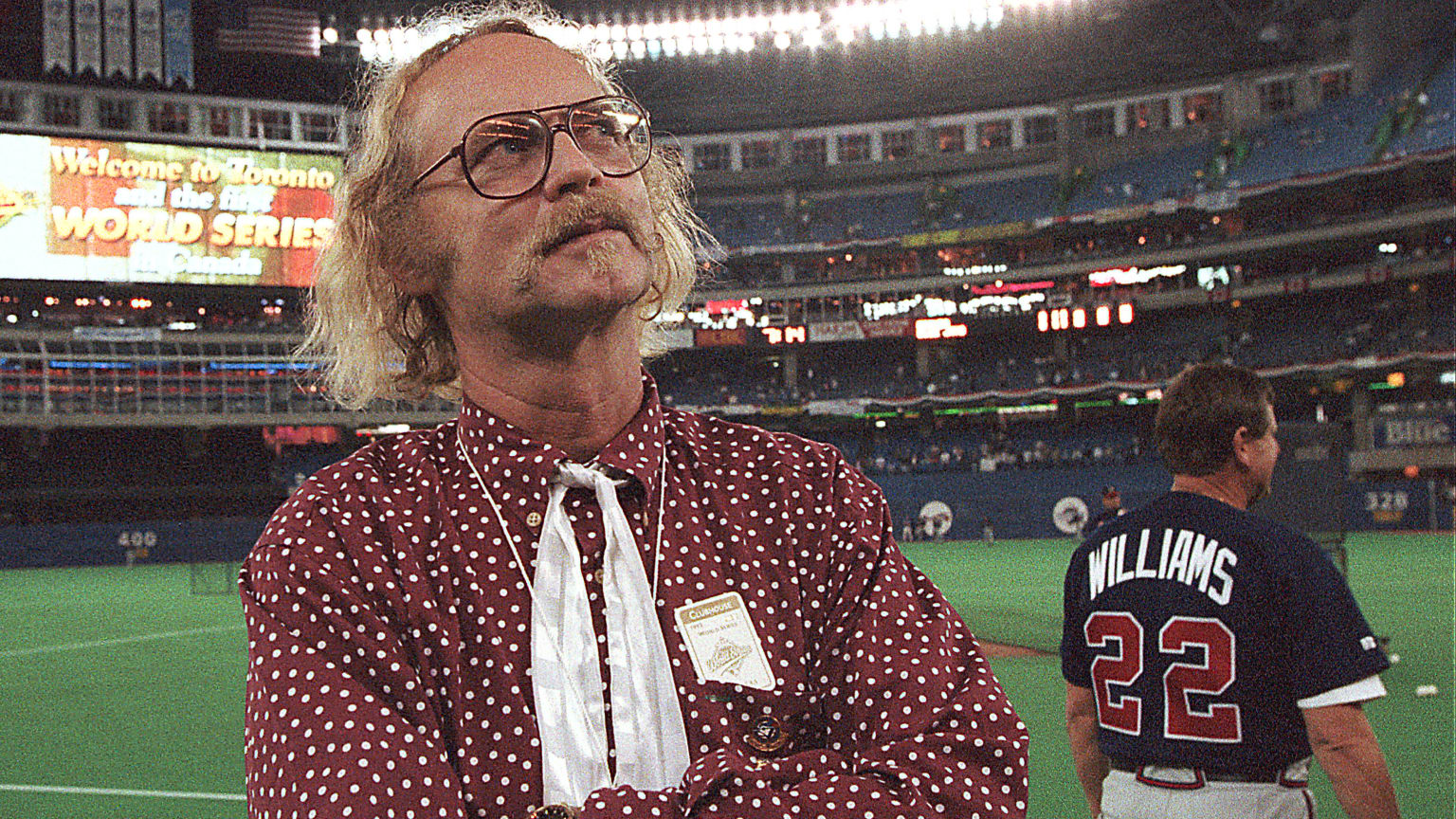

“Field of Dreams” is adapted from the 1982 book called Shoeless Joe by the Canadian writer W.P. “Bill” Kinsella. The reclusive author in the book is named J.D. Salinger. Salinger apparently did not appreciate being in the book but didn’t sue to block it, however, he apparently warned that he’d never allow a movie portrayal. So the film character was changed and played by James Earl Jones, although some of the descriptions in the movie are fairly clear that this is someone a lot like Salinger.

Phil Alden Robinson, the director and writer of “Field of Dreams,” was born in 1950, and his personal timeline seems similar to that of Ray Kinsella. Robinson had previously written the Steve Martin-Lily Tomlin soul-sharing farce “All of Me.” A few years ago, he gave this interesting recollection about “Dreams”: “When I read the book, I just kept seeing these really visual scenes and really compelling characters and surprises every few pages.”

The characters aren’t really compelling, and the surprises are downright strange. But those “visual scenes” ... that ballfield is Robinson’s grand slam, which is not even giving him enough credit; it’s a Hollywood accomplishment on the level of Johnny Vander Meer’s back-to-back no-hitters. No matter what else is going on in this movie, the notion of a magic ballpark in someone’s back yard where deceased baseball greats return to play and share life tips with us is the perfect visualization for anyone who ever owned a baseball card, who ever memorized the list of all those players with 3,000 hits, who ever stepped to the plate in wiffle ball and announced “Mickey Mantle’s up.”

Paired with the park is one of the most recognized movie phrases of the 1980s, “If you build it, he will come.” During production, it probably didn’t seem like a million-dollar line, but it’s to Robinson’s credit that he put forth a unique slogan that could catch fire. It’s often converted into “people will come” or “they will come” by people seeking inspiration for a new project. Robinson shrugged that “I often hear it misquoted.”

Most of Hollywood, apparently, missed the forest through the corn, which tells you something about the (limited) inspiration out there. Robinson says of studios’ initial reaction to the material, “They all just said no.” He said Larry Gordon, a legend and then of Fox, and Scott Rudin saw the potential and took the “leap of faith” to get the film made. Gordon left Fox and eventually sold the project to Universal, which made the picture.

The underlying drama in “Field of Dreams” is a financial one and is completely non-visual. We learn, through an obnoxious, cartoonish (but funny, with his Easter bunny comment) in-law whose motives may either be pure (saving his sister from a crackpot husband) or dubious (sensing a chance to flip some valuable farmland) that lenders are going to foreclose on the farm — not before the ballfield is built, only after. The in-law seems far more agitated about this than the Kinsellas are. Even so, fulfilling whatever this adventure is all about within a short period of time will be paramount for Ray Kinsella’s livelihood.

Warren Beatty said that a big part of the appeal of “Heaven Can Wait” is that “it says you’re not going to die.” There’s some of the same formula in “Field of Dreams,” which qualifies for the time-travel genre even if not a typical example. Death is not the end, only a boundary. Virtually every one of us wants, someday, another moment with our parents. (It helps when they’t not bickering with us in the way we remember but are relaxed and kind and gracious.) And the idea that the afterlife includes a sort of Google indexing of whichever celebrities matter most to us is reinforced by “Field of Dreams” (even though the movie predates Google).

Much of the movie is Kevin Costner mugging for the camera with a befuddled look on his face. He’s a great actor; he’s successful at this approach. On the other hand, his co-star Amy Madigan, who is well cast, tries a little too hard to out-act him. They do, in fact, seem like a natural couple, rare for movies, except she seems to yield rather easily to his determination to upend their livelihood by responding to the visions and voices he’s receiving. Robinson apparently found that reaction in the book a difference-maker. It would be more convincing if she opposed this idea on common-sense grounds and relented after Ray explained how beautiful the concept might look.

One of those questions on the SAT or ACT college test might say something like, “Regret is to Redemption as ... ?” If that seems illogical or unanswerable, “Field of Dreams” won’t help you out. The protagonist has a major regret. The doctor has no regret, just maybe a wish that has to be prodded out of him. The author doesn’t seem to have much regret either; he concludes that he has been chosen to witness the inner workings of the cornfield simply so that he can “write about it.” Shoeless Joe, our chaperone on this tour? He appears not to have any regret, just a mild chip on his shoulder — that he got screwed, but oh well.

“Dreams” moves along quickly, it’s a breeze to watch, save for its brief detour into camp in the ghastly showdown in Terence Mann’s apartment. (A similarly dreadful sequence takes place in the duel between two women at the massively attended book-ban meeting.) Unfortunately, the movie is just not funny. Costner has a few potentially amusing lines, such as his “What do you want?” question at the ballpark and at the ending, when he wonders “What’s in it for me,” but the humor is uninspired, weighed down by the characters’ solemnity toward this odyssey. In general, that’s not good. “Heaven Can Wait,” which also has an emotional hook, has great lines everywhere.

Like “Back to the Future,” “Field of Dreams” will introduce a modern character at current age to a parent at a younger age. They will share a simple but enormous moment, except that the parent, at this age, will never grasp the significance of this encounter. Frustratingly, several characters somehow know there is a heaven but are confused enough to think this Iowa cornfield is it. One character describes heaven as “the place dreams come true.” On the field, it’s unclear why the players are there — these are either practice sessions or light pick-up games, albeit with neatly dressed umpires.

Gene Siskel gave the movie two stars, explaining, “Too many characters and too many stories crowd the field.” His Chicago Tribune colleague Dave Kehr was a little more generous with three stars, though Kehr claims that Moonlight Graham “had one at-bat in the majors before moving on to medical school,” which suggests Kehr wasn’t paying close enough attention (he does note that “the audience is asked to decode” the film). Kehr says the movie is a “Spielbergian” effort and praises Robinson’s vision but complains there’s “something uncomfortably manipulative about it” and that “you still leave it feeling a little used, as if Robinson had stolen something private and personal and sold it back to you.” Roger Ebert argues that “movies are often so timid these days” and therefore “there is something grand and brave” about this one.

Archibald “Moonlight” Graham was a real person and a real ballplayer. If you thought the movie’s interviews with people in Minnesota seemed like the type of material that only comes from someone’s personal experience, you’re right — Bill Kinsella found Graham’s name in a baseball reference book and talked to people in Minnesota and invented a dream to go with this unique baseball story. (The movie did its “Minnesota” filming in Galena, Ill.) The real Graham died in 1965; Robinson said he changed the year to 1972 “simply because I wanted to have a Nixon poster in the shot.”

Probably most of the people watching “Field of Dreams” in theaters in 1989 had never seen Burt Lancaster. His appearance helps make “Dreams” special though it feels unnecessary because the drama is associated with his younger self and his townspeople have already revealed what the older Doc was like. Robinson said that Lancaster was not in great health and that filming on hot days in an overcoat was not easy for him. He was 75 at the time of the movie’s release and died in 1994.

Thousands of words could be spent debating whether “Field of Dreams” is a plus or minus for Iowa. Today, the Dyersville ballfield(s) is a massive source of pride and perhaps the state’s No. 1 tourist attraction, however that may be quantified, certainly whenever Major League Baseball plans an event there, as it did with a real game in 2021. But the field’s history is a little complicated. Universal actually built two adjacent fields so that it could capture scenes with different angles of light. The land encompassing the fields happened to be owned by separate parties, which complicated post-film-release decisions about how to handle the property and obvious tourism to come. Nevertheless, the “field” depicted in “Dreams” tops Chatsworth’s Mason Park in suburban Los Angeles (“The Bad News Bears”) as Hollywood’s most hallowed diamond.

The Dyersville area home pages do not feature the field as prominently as you might expect; perhaps the movie’s notoriety has worn thin locally. The natives in the movie aren’t exactly portrayed as the most enlightened people, and the movie seems to indicate the state’s only business is farming and its average age is 63. One sympathetic character will declare that “People will come” to Iowa, “for reasons I can’t even fathom.”

There are very few movies about farming, and rather than freedom and satisfaction, most probably dwell on backbreaking work or boredom or risk of disaster (“Days of Heaven,” “The Grapes of Wrath,” “The Wizard of Oz”). There is very little farming even in “Field of Dreams,” but there are plenty of visuals, and these are the home runs. The beauty of the green, the open space. The final scene is a Hall of Famer and portends how this movie and its setting will be viewed for a long time still to come.

The mid- to late 1980s brought a renaissance in baseball movies. There was “The Natural,” “Bull Durham” and “Major League,” all big hits. The most famous baseball movie to this day is probably “Pride of the Yankees,” but somewhere in the mix is “The Bad News Bears.” The budget of “Dreams” was reportedly $15 million and the gross was reportedly $84 million. It also proved successful among the critical community, receiving Oscar nominations for Best Picture, Adapted Screenplay and James Horner’s Original Score, which lost to Alan Menken, “The Little Mermaid.” Best Picture and Adapted Screenplay Oscars went to “Driving Miss Daisy,” which collected four statues that year.

Probably the biggest criticism about “Field of Dreams” stems from Shoeless Joe Jackson batting right and throwing left, while the real ballplayer did the opposite. This curious decision helps us evaluate the significance, or lack thereof, of movie accuracy. In this instance, the actor (Ray Liotta) was deemed the correct actor, but his left-handed swing didn’t look good enough, even after training with USC legendary coach Rod Dedeaux and former Baltimore Orioles star Don Buford. Options included either finding another actor, or simply flipping the film (this happens inadvertently in “Rocky III,” when the name on Clubber’s trunks is reversed as editors obviously wanted the shot to come from the opposite angle), which would require careful attention to detail with the rest of the set, such as Costner having to pitch left-handed. Both alternatives were spurned. Robinson said criticism came from a “small corner of people” and he shrugged it off; “I have to say, I truly didn’t care.” He joked that there’s an even bigger inaccuracy that no one faulted, that Shoeless Joe could be playing baseball in Iowa in 1986.

That’s maybe a bit cavalier about his own work. Yes, viewers will accept Shoeless Joe Jackson appearing in an Iowa cornfield decades after his death. That’s a premise, which has unlimited latitude. How Shoeless Joe bats and throws is a detail that in this film casts at least some doubt on this premise. If Ray Kinsella is so fond of this ballplayer and knows his statistics and life story, why is Ray not the least bit skeptical to see this person batting right-handed? Shouldn’t he wonder if he’s being had?

Liotta has a tougher reaction to the decision than Robinson, saying in the DVD commentary, “To this day I regret it because I’m a bug, making sure things are accurate.” Like Robinson, Liotta concluded, “Well, he didn’t come down from heaven either, so ...” The right-handed-batting decision is a major flaw of this film. But not a deal-breaker.

Robinson concedes that the Shoeless Joe of “Dreams” is far more eloquent and poetic than the real person undoubtedly was. That is not nearly as questionable as right-handed or left-handed. Behind the scenes, “Dreams” is surely a deep dive into legalities involving usage of real people’s likeness. If someone says in some movie that he saw Babe Ruth hit his 60th home run, no one from Ruth’s estate is going to file an injunction. If, however, a Ruth character is cast in a movie, then you’ve got a potential collision of artistic license vs. commercial licensing. Only an entertainment lawyer could (possibly) say for sure what depictions might require money. Dubious players from a 70-year-old team are probably fair game. The movie’s intro curiously includes depictions of three Cracker Jack baseball cards of the 1914-1915 era showing Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Joe Jackson — Ruth and Gehrig are not in that set; Jackson is, but with a different image on the card than is shown in the movie, in the same way movies showing someone on the cover of Time magazine will use a picture of the actor and not the real person. Ty Cobb’s name is mentioned in the film, but he’s not portrayed, unlike the curious mix of Smoky Joe Wood, Mel Ott and Gil Hodges, whose estates all must have assented. “We used the names of the original Black Sox players. We took real liberties with portraying them,” Robinson said.

Public fascination with Shoeless Joe comes and goes. “Field of Dreams” is one of two films of the late 1980s featuring him prominently, the other being “Eight Men Out.” Some of these players, unfortunately, were bona fide s.o.b.’s. They were indicted but acquitted at trial; their punishment came from new Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who banned them from the game. Every so often there’s a petition drive to get Jackson into the Hall of Fame, but baseball people don’t seem to want to upend a decision made in the 1920s. Maybe those fans see Jackson as one of the sport’s most tragic figures. Or maybe they just love that nickname.

3.5 stars

(July 2024)

“Field of Dreams” (1989)

Starring

Kevin Costner

as Ray Kinsella

♦

Amy Madigan

as Annie Kinsella

♦

Gaby Hoffman

as Karin Kinsella

♦

Ray Liotta

as Shoeless Joe Jackson

♦

Timothy Busfield

as Mark

♦

James Earl Jones

as Terence Mann

♦

Burt Lancaster

as Dr. ‘Moonlight’ Graham

♦

Frank Whaley

as Archie Graham

♦

Dwier Brown

as John Kinsella

♦

James Andelin

as Feed Store Farmer

♦

Mary Anne Kean

as Feed Store Lady

♦

Fern Persons

as Annie’s Mother

♦

Kelly Coffield as Dee, Mark’s Wife

♦

Michael Milhoan

as Buck Weaver (3B)

♦

Steve Eastin

as Eddie Cicotte (P)

♦

Charles Hoyes

as Swede Risberg (C)

♦

Art LaFleur

as Chick Gandil (1B)

♦

Lee Garlington

as Beulah, the Angry PTA Mother

♦

Mike Nussbaum

as Principal

♦

Larry Brandenburg

as PTA Heckler

♦

Mary McDonald Gershon

as PTA Heckler

♦

Robert Kurcz

as PTA Heckler

♦

Don John Ross

as Boston Butcher

♦

Bea Fredman

as Boston Yenta

♦

Geoffrey Nauffts

as Boston Pump Jockey

♦

Anne Seymour

as Chisolm Newspaper Publisher

♦

C. George Biasi

as First Man in Bar

♦

Howard Sherf

as Second Man in Bar

♦

Joseph Ryan

as Third Man in Bar

♦

Joe Glasberg

as Customer

♦

Mark Danker

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Frank Dardis

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Jim Doty

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Mike Goad

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Jay Hemond

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Mike Hodge

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Steve Jenkins

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Terry Kelleher

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Ron Lucas

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Fred Martin

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Curt McWilliams

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Jude Milbert

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Steve Olberding

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Gene Potts

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

James Roth

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Paul Scherrman

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Dale Till

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Tom Vogel

as Additional Ballplayer

♦

Brian Frankish

as Clean-shaven Umpire

♦

Jeffrey Neal Silverman

as Clean-shaven Center Fielder

♦

Ed Harris

as The Voice

Directed by: Phil Alden Robinson

Written by: W.P. Kinsella (book)

Written by: Phil Alden Robinson (screenplay)

Producer: Lawrence Gordon

Producer: Charles Gordon

Associate producer: Lloyd Levin

Executive producer: Brian Frankish

Music: James Horner

Cinematography: John Lindley

Editing: Ian Crafford

Casting: Margery Simkin

Production design: Dennis Gassner

Art direction: Leslie McDonald

Set decoration: Nancy Haigh

Costumes: Linda Bass

Makeup and hair: Enid Arias, Richard Arrington, Donald Morand, Elle Elliott,

Bonita DeHaven, Lesly Erhman, Sharon McDonald, Cindy Stratton

Unit production manager: Brian Frankish

Stunts: Randy Peters, Debbie Lee Carrington

Special thanks: Rob Abel: Dubuque Area Chamber of Commerce

Special thanks: Connie Trencamp: Dyersville Chamber of Commerce

Special thanks: Wendol Jarvis: Iowa Film Office

Special thanks: Susan Reynolds: Iowa Film Office

Special thanks: Al Amescamp

Special thanks: Don Lansing