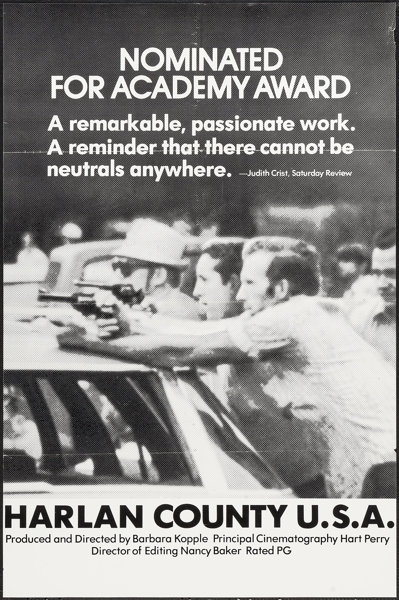

‘Harlan County U.S.A.’ could stand a little more tunnel vision

“Harlan County U.S.A.” took 26-year-old upstart Barbara Kopple about four years to finish. Had she stopped at one, she probably would’ve had a helluva movie.

“Harlan County” is assuredly for the little guy. That’s a must. The best documentaries express a point of view; imagine filmdom’s reaction if Kopple spent four years chronicling and championing the struggle of a coal company.

The problem is, the project didn’t start with the little guy. And it didn’t end there, either. And viewers inclined to cheer “Harlan County” the way they cheered “Norma Rae” might well wonder by the end if they shouldn’t just be disillusioned by the whole thing.

Kopple’s film is rightly considered a landmark effort for a couple of reasons, its extended intimacy with the American poor and the fact it was made by a woman on a meager budget who elicited funds from foundations and church groups and put expenses on her Master Charge account. Indeed, there’s a legitimate argument that Kopple, not the people she films, is the real hero. It took time to gain a rapport with the community, but Kopple is approachable and striking. There are a few moments where people in the film indicate the presence of cameras is affecting their actions. Kopple said decades later, in a retrospective on the film presented by the Criterion Collection, that her crew probably did “keep down violence, because nobody wants to commit murder in living color.” One of her film’s featured miners, Jerry Johnson, bluntly adds, “I really don’t think we would’ve won that without the film crew. If the film crew hadn’t been sympathethic to our cause, we would’ve lost. ... Thank God they were on our side.”

Let’s start, as Kopple did, from the top. “I remember that I had read about the murder of Joseph ‘Jock’ Yablonski and his family in the newspaper,” said Kopple at a Sundance screening in 2005, “and there was an uprising within the United Mine Workers where a leader from the coal fields was going to fight against W.A. ‘Tony’ Boyle for the leadership. And then, miraculously, he got in, and his pledge was to organize the unorganized. And Harlan County was that place.” That is what people in the news business call a good lead. But Kopple overreached: “So, off we went to Harlan County to see if he kept his promise.”

The answer presumably was “no.” That “leader from the coal fields” was Arnold Miller, whose Wikipedia page says he “proved to be a weak president” whose meetings “spiraled out of control.” Miller supposedly kept a baseball bat by his desk and, like the replacement workers in Harlan County, brought a handgun to union gatherings. He even, like Boyle, “began using a huge limousine.”

So much for the little guy.

Throughout “Harlan,” Kopple persistently tries to link the beleaguered Kentucky strikers to the dysfunction at the national union level. But this correlation, visually and thematically, is a zero. It is the equivalent of filming the same community to demonstrate the effectiveness of Senator Mitch McConnell’s policies. Miller comes to Harlan County fairly late in the documentary, and there’s no indication that anyone wanted him to. Busloads of sympathetic miners from Indiana and Illinois are brought in to lend support, a move praised by national leaders. But a Harlan County striker grumbles to Kopple, “To bring people hundreds of miles to just march around town and listen to a couple speeches don’t make too much sense to me ... a lot more could’ve been done when they came here”; for example, they could’ve “marched down to Brookside” or “expropriated their machine-guns.”

Gary Arnold in a March 23, 1977, review in the Washington Post, writes that “Kopple may have complicated the film unnecessarily by trying to incorporate too many developments. One is left with the impression that Kopple was reluctant to finish the film, that she kept wanting to add foot-notes and bulletins.”

The inclusion of national union figures, with just token descriptions of who these people are, only waters down the impressive street fight that Kopple finds herself a part of. The stars of her film should be Lois Scott, the most vocal striker advocate, and Basil Collins, who leads replacement workers to and from the mine. He occasionally draws a gun. And so does Scott. Each has a dogged determination — they seem to relish this conflict — and a considerable level of charm. (Sadly, it must be noted that Collins is heard uttering a racial slur.)

Collins may see himself at the vanguard of freedom. He tells Kopple, “What do you think when unions are destroying our whole country. Mr. Hoffa’s in the penitentiary, the Teamster Union are known communists, the Longshoremen are known communists, every union in the country striking, what will happen to our country.” But Collins and Scott are far more eloquent on the local level. Each knows all the rules, where they can stand, what they can say, baiting the sheriff and deputies the way basketball coaches badger referees. Who knew that in Kentucky, apparently you can get someone arrested for $7 and change. Court injunctions allow, at least at some point in this conflict, only six people on a picket line at once. Perhaps because of the cameras’ presence, it seems Collins’ best weapon is patience. Eventually the police will clear the roads, and most of the strikers will go home.

That sparring is compelling. But gradually, it looks as though Collins and Scott have done this type of thing too many times. Enough that “Harlan County U.S.A.” begins to look less like an existential struggle and more like an ordinary hiccup of a troubled industry. Kopple’s cameras are there for clashes, but no other news media appears to care. Collins and Scott seem to know, or know of, each other. “He had the nerve enough believe it or not to run for sheriff,” according to Scott, who is a “miner’s wife, all right, but from a neighboring town,” according to Pauline Kael. One woman who is seen taking part in strike-related activities declares at a meeting that Scott has “done nothin’ but cause trouble” and tells her directly that there’s a belief “that you’re running around with their husbands, that you’re trying to take their husbands away from them.” Scott accuses the woman of being an “alcoholic.”

What say the families on the front lines? Pickets are actually rarely seen in the film; there is more whittling than sign-carrying. Kopple includes several references to a lack of interest. Strikers are occasionally seen smiling at the meetings. About 10 minutes into the film, at one meeting, an organizer says he’d like members to sign up for picket duty; no one seems particularly gung-ho. At another point, a union organizer notes that sometimes, there are only two or three people on picket duty and that “very rarely” do they see six. Later, the miner Jerry Johnson complains, “I don’t think you’ll never (sic) win a strike by having six people on the picket line ... so you gotta violate these injunctions.”

The best scenes of “Harlan County U.S.A.” are the opening ones, how the miners enter the mine, what kind of space they operate in. The scenes are intimate enough that claustrophobic viewers may have trouble getting through them. We see the stark visuals of obvious risks, tiny tunnels, ceilings that could collapse, dangerous machinery that with one wrong move or malfunction could take an arm or leg or worse. Finally the coal comes streaming out on its own conveyor, beautiful black piles, nice and orderly.

How did Kopple manage this kind of access for a film supporting the workers? Well ... and this is an enormously important skill of documentary or advocacy filmmakers, from Charles Burnett’s “Killer of Sheep” to “The China Syndrome” … Kopple cleverly avoided telling the mine company what she was doing. She told the New York Times in 1976, “We were not allowed to film the coal mines at first, but I wrote letters telling people I had come from New York, where there is little industry, and that I had never seen anything like the mines. I didn’t tell them exactly what we were doing, but it was pretty much the truth, and we got into mines no one else would have been taken to. I just shut my mouth and watched and listened and tried not to show how little I knew.”

“Little industry” in New York? That account is slightly different from what photographer Hart Perry offers in the Criterion Collection retrospective. Perry says, “After several months of filming, I realized we didn’t really have too much coal mining.” So, “I approached a local mine operation, explained I was interested in, uh, you know, coal mining, and how it worked. And they let us film in mines, low coal, we were a mile underground.” So what “local” mine, and what workers, are we seeing in those opening scenes? There is something called artistic license that protects Kopple here.

Kopple, or her voice, dodges the truth in the film when she is having a conversation with Basil Collins and tells him she works with “United Press,” which to many people would sound like a shorthand name of the respected and now-shuttered wire news service. Collins doesn’t appear to believe her and asks for a “press card,” which Kopple declines to produce. He says he seems to have lost his own ID cards. He chuckles at their little showdown.

A beautiful sequence takes place on Wall Street. Some of the miners have been brought to New York City, and one of them, Jerry Johnson, is secretly miked while chatting up a New York police officer — who sounds more like the striking miners while Johnson sounds like a coal exec. This conversation is too good for Kopple to omit even though it undermines much of the rallying cry of the movie. The officer agrees with Johnson that 42-inch-high tunnels are difficult places to work, then suggests that coal companies “make good profit but they keep it all themselves, right?” Instead of agreeing, Johnson insists, “We get paid real good.” The officer scoffs that it’s only $5-$6 an hour; “I make more than that.” Johnson explains, “We draw union strike benefits.” The officer suggests his own job is easier, for higher pay. “Look at me, this is what I do, it’s a lot of bullsh--.” Johnson points to skyscrapers and stresses the strikers’ interest in safety: “One man dies every day” for that electricity. The officer gets dental, the miners do not. The cop boasts that he can retire at 36 at “half pay,” presumably not an option for Johnson.

The holy grail of “Harlan County U.S.A.” is what’s called “The contract.” For a filmmaker, that's a problem. “The contract” physically is a paper booklet. Emotionally, it’s a lot more. To many viewers, Kopple is simply showing strikers demanding a better deal. Actually, what you’re seeing is the prequel: They are demanding unionization, which on certain levels they haven’t achieved because it requires company recognition that hasn’t occurred. Depicting a company, and perhaps its strikers, making concessions is a tough ask.

The famous documentary “Gimme Shelter,” which Kopple worked on, includes startling footage that is still mentioned in pop culture today: the killing of a Rolling Stones fan at a poorly supervised mega-concert. It appears that a similar seminal moment ended the Harlan County standoff: the shooting death of young striker Lawrence Jones. But Kopple has no footage of Jones’ death, save for a purported chunk of his brain (yes, that is what the bystanders say) on the pavement. The revelation of this tragedy comes out of nowhere around the 80-minute mark. A couple of times, strikers name whom they believe to be the shooter. According to comments in the film, a grand jury refused to indict. Kopple does record a separate shooting incident in the dark in which no one appears to be hit. Who started the shooting and who’s responsible seem hopelessly unprovable. There’s still a powerful message here: You can die doing this, even when you’re not working.

In a subsequent union meeting, an older man says, “The contract is what we are fightin’ for. That’s what Lawrence Jones died for. To get a contract. ... It took a young man’s life ... if this shooting hadn’t a happened, probably this contract, they wouldn’t probably might not’ve been a meetin’. To negotiate a contract.”

For all of her access, Kopple virtually never sits down with a miner or his wife, one on one, to ask what they think of the job or the union. Yes, this is much easier for a veteran crew with deep pockets. Many of these interviews will yield hours of unusable material that independent filmmakers can’t afford. But a few of these interviews will hit paydirt, miners or supporters expressing in a few candid remarks, away from the presence of colleagues, something that epitomizes the battle.

Throughout the film, the song and/or slogan “Which side are you on” is heard. This being her directorial debut, Kopple had yet to realize that repeating the same song is bad form. Who are those lyrics directed at? It is quietly implied that there is sufficient interest in the area for crossing the picket line. It’s entirely possible there are people from the same neighborhood taking each other’s jobs. There is considerable evidence in “Harlan,” as in “Norma Rae,” that not everyone in town was sold on the union. Surely some of the strikers and their families must be wondering if this organizing, and strike, is the right move.

Folk songs are so common in “Harlan County U.S.A.,” Kopple actually flirts with turning this drama into a musical, something more akin to Woody Guthrie’s “Bound for Glory,” coincidentally released the same year. The tone of the “Harlan” songs evokes not only Appalachian struggles but Vietnam-era protests. Gary Arnold, in his Washington Post review, observed, “Kopple’s worst stylistic habit is superimposing songs over sequences that don’t need them as either commentary or transition. It’s almost as if she got accustomed to living and working with a constant accompaniment of folk songs and/or union songs and couldn’t do without them, even when they become obtrusive.”

According to the 1976 New York Times account, Kopple had, prior to her Harlan County stint, spent time in Ohio and West Virginia coal territories interviewing miners battling black-lung disease. These stricken miners, including Arnold Miller, had forged a political bloc within the United Mine Workers that drew Kopple’s attention prior to the Harlan County strike. When her cameras address this scourge in “Harlan County U.S.A.,” the presentation is highly effective. But the footage could’ve been more potent. It’s spaced too far from the scenes of healthy miners at their daily work. The message could’ve been less piecemeal: If a mine accident doesn’t kill ya, the stuff you’re breathing quite possibly will. How much protection from black lung are strikers hoping to receive? The subject fades. A physician declares that Australia believes it has basically solved the problem of black-lung disease, but he doesn’t explain how and apparently isn’t asked.

There are several moments where the people in “Harlan” are funny. Sudie Crusenberry, who was nominated to take a leadership role among the strikers’ wives, breaks up an argument by saying, “I’m not after a man, I’m after a contract” and, referring to allegations of female instigators seeking male companionship, adds, “If they take mine, if they take him on, they can have him; I’ll shed no tears.” During the miners’ Wall Street picketing, an African American woman passes by and asks picketers, “You from the South? ... You look like you’re all from the South.” Strikers and supporters joke at being jailed. Basil Collins asks the sheriff, who is handling the situation in plainclothes, why he’s being arrested and hears, “Disorderly conduct I guess; I don’t know.” Even at a tragic moment, a union veteran speaks after the death of Lawrence Jones and puts it this way: “Why couldn’t it be somebody like me, some old man just about spent anyhow.”

Houston Elmore, a United Mine Workers organizer, says of Harlan County with a straight face, “It’s a feudal system, I think. There is a very rich class of people, and then there are the coal miners, and then there are the people who are on relief, and that’s about it in Harlan.” Kopple somehow overlooked the neighborhoods of the “very rich class.”

There’s an unfortunate but inescapable motif in “Harlan County” — bad teeth. Sometimes, Kopple’s cameras are so intimate, watching people talk is cringeworthy. Is such an observation a cheap shot? Not in this kind of grass-roots documentary, and not when the offenders include Duke Power President Carl Horn. Pauline Kael noted “the missing teeth, the collapsed jaws.” These people may not have the Pepsodent look, but they are 100% real.

Whatever the film’s flaws, Kopple’s extraordinary effort was richly rewarded. She collected the Oscar for documentary feature of 1976, besting Michael Firth’s “Off the Edge,” Anthony Howarth and David Koff’s “People of the Wind,” James C. Gutman and David Helpern’s “Hollywood on Trial” and Donald Brittain and Robert A. Duncan’s “Volcano: An Inquiry Into the Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry.” It was no fluke. Kopple collected a second Oscar for her 1990 work “American Dream,” with Arthur Cohn.

“Harlan County U.S.A.” (Kael decided including “U.S.A.” in the title is an unneeded “dig”) is a merry-go-round of complaints, grievances and grudges. Viewers will almost certainly find themselves wondering, “This isn’t utopia. Why don’t these people just get outta here?” They’ve risked their lives, heard the b.s., sang the songs many times before. The film is peppered with references to previous coal-mining struggles, notably deadly eastern Kentucky clashes in the 1930s. One white-haired resident says that in the 1930s, the politicians, union and “Catholic hierarchy” were all in cahoots with the coal company, and that workers had to battle the “whole combination ... a regular guerrilla warfare.” These kinds of us-against-the-world observations, interspersed with 1970s footage of the legal troubles of national mining figures, gradually add up to the realization, this is just another brick in the wall.

Kopple had previously worked on “Hearts and Minds,” an exceptional documentary released in 1974 that narrowly contrasted the United States involvement in the Vietnam War as an existential struggle for the Vietnamese and a football game for American rooters. Kopple in “Harlan County” has shown us too much and delivered something in between: that her subjects have been there, done that, will do it again, and know which side they’re cheering for.

3 stars

(June 2019)

“Harlan County U.S.A.” (1976)

Featuring: Lois Scott ♦

Basil Collins ♦

Norman Yarborough ♦

Houston Elmore ♦

Phil Sparks ♦

John Corcoran ♦

John O’Leary ♦

Donald Rasmussen ♦

Hawley Wells Jr. ♦

Tom Williams ♦

Chip Yablonski ♦

Ken Yablonski ♦

Logan Patterson ♦

Harry Patrick ♦

Mike Trbovich ♦

Bernie Aronson ♦

Guy Farmer ♦

Nimrod Workman ♦

Bessie Lou Cornett ♦

Jerry Wynn ♦

Bob Davis ♦

Joe Dougher ♦

Jerry Johnson ♦

Sudie Crusenberry ♦

Dorothy Johnson ♦

Betty Eldridge ♦

Ron Curtis ♦

Bill Doan ♦

Phyllis Boyens-Liptak ♦

Florence Reece ♦

E.B. Allen ♦

Jim Thomas ♦

Mickey Messer ♦

Nanny Rainey ♦

Tom Pysell ♦

Tommy Fergerson ♦

Bill Worthington ♦

Crystal Fergerson ♦

Barry Speilberg ♦

Polly Jones ♦

Diane Jones ♦

Otis King ♦

Mary Lou Fergerson ♦

W.A. ‘Tony’ Boyle ♦

Carl Horn ♦

Lawrence Jones ♦

John L. Lewis ♦

Arnold Miller ♦

William Simon ♦

Richard Trumka ♦

Billy G. Williams ♦

Joseph Yablonski ♦

Hazel Dickens ♦

Barbara Kopple

Directed by: Barbara Kopple

Producer: Barbara Kopple

Cinematography: Kevin Keating, Hart Perry

Editing: Nancy Baker, Mirra Bank, Lora Hays, Mary Lampson

Music: David Morris