Bored rebel ‘Maria’ finds

authority tough to swallow

Everyone’s first trip to New York is a big deal. Most arrive as tourists. Others come for the business.

Most of the businesspeople will instruct the cabbie to make a beeline from JFK to Manhattan. It is a true entrepreneur, or explorer, who stakes her claim in Queens.

Maria Alvarez, a 17-year-old Colombian peasant, doesn’t seem like she could possibly be in the latter group, but she is. New York might be “too perfect,” as a friend says, but Maria can’t afford to be spellbound — she is risking her life at a very dangerous job.

From the beginning of “Maria Full of Grace,” we learn why she might be put up to it. She, her mother and a close friend rise early, to board a bus in the dark that will take them from their rural village to jobs, somewhere, miles away. The jobs are going to be in a factory, and they are probably not bad jobs given the geography, although they might raise child-labor issues. Maria and her friend work in a floral center where they strip the thorns from flowers. Their factory, actually, is safer than the one in “Norma Rae.” The women wear modern safety equipment, the place is clean, the boss is professional.

Were this factory located on American soil, it would no doubt be staffed by the same type of people as Maria: poor, non-white, in many cases likely non-American. That does not make it a dead-end job. The point is made, maybe even incidentally, of the value of this work, that the people who buy flowers are dependent on the people in these factories because the people buying the flowers would never do this work themselves.

But is it a destination? It probably shouldn’t be, but that depends. Maria’s mother boards a different bus and works elsewhere. Her workplace is never shown, but she can easily be envisioned as a reliable worker who appreciates her reliable paycheck, supporting two daughters and a baby grandson in a home with no men around. It is a challenging, but not terrible, life.

There is nothing stopping Maria from doing the same except Maria. It’s not so much that she hates the job or is underpaid; she is bored. Colossally bored. Survival is not foremost in her mind, as it is with her mother; excitement is. Her job is uninteresting. Her boyfriend is uninteresting, and her best friend is uninteresting. If she’s going to have to do it — whatever “it” is — it better sizzle.

Bored people can get into trouble. Maria is no exception. It’s clear she has problems with authority figures. But this is no “Cool Hand” Lucas Jackson. Maria has legit grievances with everyone. Her supervisor doesn’t allow her to use the bathroom when ill (probably because he does not realize she is pregnant). Her mother demands she disproportionately help support a sister who is more or less a deadbeat. Her boyfriend ignores her, even if he does try to do the right thing. Maria is correct in calling all of them out, but she has no leverage. She has to go along to get along.

“Maria Full of Grace” is about the value of rebellion and suggests great immigrants aren’t always born, but sometimes made.

Just how bad is the economic climate of Colombia? Most Americans only know it as a cocaine producer and struggle to spell it correctly. Colombia does possess one of the better economies of Latin America and exports oil, coal and coffee as well as manufactured goods. It suffered recession in 1999 and a slow recovery but has seen impressive growth this decade. Alvaro Uribe, president since 2002 and re-elected with 62 percent in 2006 after the one-term limit was amended, is a popular figure among the upper- and middle-classes, and also in the West, particularly for his reported successes in defeating or demobilizing revolutionary or paramilitary groups. Bogota is not New York City, but Colombia has a rich cultural heritage and is not a poor nation.

There have been countless films about the drug trade, but this is one of the very few that doesn’t involve a gun. And the operation that materializes is fascinating, moreso than the farfetched entrepreneurism in “Blow.” It is a bit hard to believe that any Colombian drug lord could find nearly enough women to successfully deliver enough cocaine to make a steady profit, particularly when the police know how it works and arrestees could probably be coerced into coughing up details. But there is no doubt that “mules” do indeed exist, so that bit of disbelief is easily suspended as we await Maria’s fate.

The fact Maria is committing a serious international crime will not be lost on most people, but neither will the fact this is a mostly innocent, lightly educated person facing a bleak life, not conscious that she might be harming someone down the line. Why does she do it? Not because it’s money, or a way out of her village, or it’s exciting, but all of the above.

There might be concern among some that films like “Scarface” and “Blow” end up glorifying drug trafficking despite the fate of the protagonists. “Maria” will leave no such impression. Maria may be a heroine, but the real heroes are the immigrants she encounters in Queens, the Colombian couple she stays with that is proud to be working and sending money to the old country, the man in the insurance shop who assists newcomers and finds work for well-meaning job-seekers, and Lucy, her beleaguered associate who knows what she is doing is wrong and will regret it until the day she dies.

Maria too will learn this, but perhaps more from practicality than principle. She sees women putting their health, freedom and lives on the line, only to be treated much worse than anything that happened at the flower factory. To accept such a job is to seriously compromise not only values, but possibly survival.

A compelling relationship is developed throughout between Maria and her best friend, Blanca. They are the perfect contrast. Maria is a leader, Blanca is a follower. It is Maria who must guide Blanca to her obvious boyfriend, and it is Maria’s decision to join the mule business that prompts Blanca to do the same. Blanca wants to think Maria is foolish, but inevitably she’ll return to ask Maria, “What do we do now?” A poignant scene of their final split, though not without flaw, is one of the strongest of the film.

Director and writer Joshua Marston is a Southern California native (born 1968) with a very limited body of work. He graduated from Beverly Hills High School but tried journalism for a while and even received a master’s in poli sci from the University of Chicago in 1994 before earning a master’s in fine arts from NYU.

He proves to be highly skilled at the art of the unexpected. The first scene to catch us off-guard is when Maria and Blanca look at a young man in a cafeteria who apparently likes Blanca, only to cut to a scene of Maria in the throes of a passionate kiss. This transition is not quite perfect because we are briefly fooled, thinking for a moment she has stolen Blanca’s boyfriend (something she would be capable of doing) and requiring a later scene to clarify these relationships.

But Marston is in a groove in several other instances. In one, Maria’s boyfriend surprisingly wants to do the right thing. But this scene gets even better when Maria turns on him and calls him out for his faults. He may be the more noble, but she is ahead of the curve.

There is a scene in the flower factory where Maria is being punished. Her boss hands her a hose and orders her to spray-clean all of the roses. Any viewer paying attention is expecting to see her turn the hose on her boss and laughingly walk away.

Airport security is usually depicted in extreme ways, either thugs or incompetents. These customs officers are among the finest in filmdom. They are smart, efficient and compassionate. It maybe was not one of their better days to let Maria go without at least detaining her for a while; she lied to them and would seem a very likely mule candidate. Nevertheless, the interrogation and security check are deftly handled in such unpredictable ways that it’s actually surprising that it comes to an end so soon.

In New York, the reappearance of Blanca — and Maria’s assertive demand that Lucy be paid — occur unexpectedly. If there is any flaw to be found in these excellent twists, it is the scene showing Maria and Blanca in the airport line that appears to be trying too hard to fool us.

It might be that Maria is, at times, a bit too sure of herself for a 17-year-old criminal in a foreign country. The plane flight she takes is almost certainly her first, but neither she nor Blanca seems the least bit fascinated or intimidated by air travel. She probably does not express the type of wonderment such a peasant normally would in New York City. But those are small details whose presence would risk bumping the film off-message.

“Tour de force” is an overused term. But this is one of them. Catalina Sandino Moreno, whose name is difficult to pronounce and recall correctly because of the last vowel in each word, was born in Bogota to a pathologist mother and veterinarian father. She was discovered in acting circles there and moved to New York for the “Maria” auditions. She was 22 when working on this film, her first. She appears essentially in every scene. It ended in an Oscar nomination for lead actress. The academy gave the Oscar to Hilary Swank for “Million Dollar Baby” — undeniably tough competition, but anyone’s vote probably could have gone either way.

Maria Alvarez would make a good president. She is wise to the ways of the world, is remarkably calm under stress and thinks rapidly as events quickly change around her. She has strong values that haven’t been fully realized. There is little doubt she is capable of running the flower factory she abandoned or perhaps, if she so wanted, even the smuggling operation she has taken part in. All she needs is some harnessing. She is Willie Mays joining the New York Giants at age 20, hitting .274. Life is calling her up to the big leagues, but she will learn the game.

One of the most poignant scenes is at home, with her mother and sister, just before leaving for New York. It might be the last time she will see her mother, who asks her why she thinks she should find “office” work in another town. Does mom really know what’s going on? It feels like she does.

That moment is superseded in New York, when Maria is telling her host she will return to Colombia, and her host explains why she herself lives in America. “Darling, you’re not going back ... I remember when I got my first paycheck. I’ll never forget going to that office to send money home for the first time. You can’t imagine how it feels...”

4 stars

(October 2008)

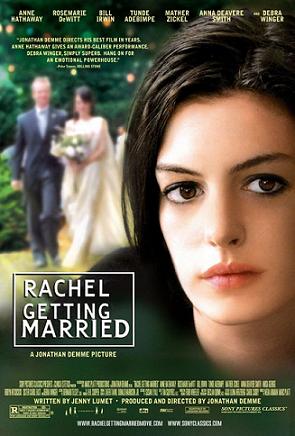

“Maria Full of Grace” (2004)

Starring Catalina Sandino Moreno as María Álvarez ♦ Virgina Ariza as Juana ♦ Yenny Paola Vega as Blanca ♦ Rodrigo Sánchez Borhorquez as Supervisor ♦ Charles Albert Patiño as Felipe ♦ Wilson Guerrero as Juan ♦ Johanna Andrea Mora as Diana Álvarez ♦ Fabricio Suarez as Pacho ♦ Mateo Suarez as Pacho ♦ Evangelina Morales as Rosita ♦ Juana Guarderas as Female Pharmacist ♦ Jhon Alex Toro as Franklin ♦ Jaime Osorio Gomez as Javier ♦ Guilied Lopez as Lucy Díaz ♦ Victor Macias as Pellet Maker ♦ Hugo Ferro as Pharmacist ♦ Ana Maria Acosta as Stewardess ♦ Ada Vergara De Solano as Carolina ♦ Maria Consuelo Perez as Constanza ♦ Ed Trucco as Customs Inspector ♦ Selenis Leyva as Customs Inspector ♦ Juan Porras Hincapie as Wilson ♦ Oscar Bejarano as Carlos ♦ Singkhan Bandit as Gas Attendant ♦ Patrick Rameau as Taxi Driver ♦ Fernando Velasquez as Pablo Aristizábal ♦ Patricia Rae as Carla ♦ Orlando Tobón as Don Fernando ♦ Monique Gabriela Curnen as Receptionist ♦ Lourdes Martin as Doctor ♦ Osvaldo Plasencia as Enrique ♦ Thomas Daniel as Tourist (JFK) ♦ Lauren Bonett as Airport PA Announcer (voice)

Directed by: Joshua Marston

Written by: Joshua Marston

Producer: Paul Mezey

Co-producer: Jaime Osorio Gómez

Associate producer: Rodrigo Guerrero

Associate producer: Orlando Tobón

Line producer: Becky Glupczynski

Line producer, Ecuador unit: Gigia Jaramillo

Original music: Leonardo Heiblum ♦ Jacobo Lieberman

Cinematography: Jim Denault

Editing: Anne McCabe ♦ Lee Percy

Casting: Ellyn Long Marshall ♦ Maria E. Nelson ♦ Maria Eugenia Salazar ♦ Jorge Valencia

Production design: Debbie DeVilla ♦ Monica Marulanda

Art direction: Yann Blanc

Set decoration: Carrie Stewart

Costume design: Sarah Beers ♦ Lauren Press

Makeup: Renee Didio ♦ Flore Marina Sandoval ♦ Evelyne Noraz ♦ Dallas Hartnett ♦ Donna Marie Fischetto ♦ Lucy Da Silva

Stunts: Elliot Santiago ♦ Manny Siverio

Special thanks: Francesca Galesi