‘Room’s’ service: Life doesn’t have a reset button

“Room” tells us things we don’t really want to know. It is to be appreciated, not cheered. It belongs in the realm of “Open Water” and “Cast Away,” beautifully done and among the most powerful statements of the here and now ever made.

Barely a decade ago, the crisis in “Room” would’ve been considered absurd. After a few well-publicized American cases, one wonders if there are many more in progress. Thankfully, they are extremely rare.

“Room” was widely released around the same time as “Spotlight.” A coincidence for sure, but a healthy one. “Spotlight” depicts society’s reluctance to address sex crimes. “Room” is the victim’s story, incomplete and a lifelong work in progress.

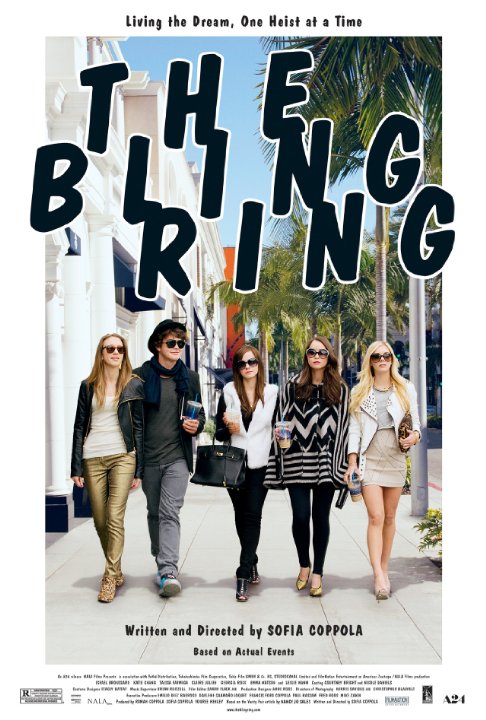

Sometimes, movie posters give too much away. It is clear from the depiction of “Room” (atop this page) that the filmmakers see a kind of triumph that might be more aspirational than the film they’ve put together.

The villain seems obvious in “Room.” But his crime is far more than plain. Society can easily eliminate his potential to re-offend. But it can’t eliminate the world of guilt that will persist far beyond his own existence. For Brie Larson’s Ma, this is a “Deliverance” type of ending, one of permanent concern. Psychology and the legal system have no appropriate remedies for her. We realize we’re making it up as we go along, with few case studies to draw upon.

“Room” establishes an important precedent in its depiction of child abuse, deciding what it will and won’t show in an American theatrical release. Jack is never struck. Rather, the script suggests Old Nick is receptive to his child, even buying him a toy. This portrayal is not necessarily unrealistic. It should forever be debated whether such a monster should be given a greater quality of fatherhood than many movie dads.

Old Nick is certainly crazy, demented, psychopathic, whatever the correct term, but he is able to function in society. His downfall is underestimating Ma, telling her she’s not very smart when in fact she outsmarts him. Perhaps after so many years, he simply was bound to let his guard down. Is there even the tiniest hint that he is tired of the situation and wants it to end? No.

What is Old Nick’s end game? Surely there must be one; his scheme has required extraordinary treachery beyond what most criminals are capable of. He knows discovery will ruin him. Moving with two captives to a new town would present enormous risk. He does not seem interested in somehow “winning” Ma over. A “regular” relationship isn’t what makes him tick. Presumably — this is the horror element — he will maintain the status quo until Ma no longer appeals to him, then end it in the worst possible way.

Hollywood has excelled at depicting life under the cruelest of circumstances. One thing we know from the movies: People don’t easily give up. Ma (she reveals her name is Joy) knows far more than the world of a shed. Her son does not. Larson’s Ma is a sanctuary, one of cinema’s most powerful heroines. The “Room” character analysis could start with “Bambi.” Deep down, suppressed, she must harbor thoughts of freedom. Any such notions, practically, were superseded by the arrival of a child. By the time we know her, she exists only to protect him. By his 5th birthday, she has concluded something very important: that however the boy gets off the property, he will be safe. Energized by this discovery, she invents a very reasonable plan that fails. The surprise is that rather than retreat, she pushes the envelope much further into a farfetched scheme. It can’t possibly work, but we accept artistic license. The risks of both of her ideas seem extreme enough, we cringe at what could happen if her plot is discovered. But her diligence is reassuring. Somehow, it feels, this has to be tried.

Viewers learn something early that all of the doctors and therapists can’t know — that Jack, despite his circumstances, is still a normal boy. Some child actors are highly celebrated, often for acting more like little adults than children, but Jacob Tremblay soars with a most reassuring performance that Jack is very much a typical 5-year-old. Ma is well aware. Has she decided that, at age 5, Jack is near an inflection point? We know she has attempted to hit her captor previously. Has she attempted other schemes? “Room” will not reveal. But we are reminded that childhood is a powerful defense, that within a few years, Jack will remember very little of the trauma he experienced.

The two halves of “Room” could each serve as a considerable film in their own right. Together, there could be a sense that one half is being short-changed. Can viewers adequately appreciate the effect of 5-6 years when it is given equal time with 5-6 months? Perhaps not. The condensing limits the sense of claustrophobia and expands parabolically the insight. “Room” will take its characters, not audience, to the breaking point.

“Cast Away” also dealt with a missing person believed dead. Both films pair the exuberance of discovery with the sober realization that life must go on and cannot be undone. But “Cast Away” assigns the problems to adults. “Room” ups the sensitivities with a child.

Many films have dealt with characters who feel slighted or unwanted. “The Social Network” would be one example, suggesting that a person could be driven to perfect the ultimate social experiment because of a campus snub.

For “Room,” dealing with an abused woman and child, the tainted concept is too grim. While Tom Hanks in “Cast Away” is forced to deal with newfound realities, Jack is presented just one skeptic — his grandfather, Robert, played by William H. Macy, who can’t bring himself to look at the boy, for reasons troubling but understandable. We have time on our side for healing. Jack will likely not remember this slight, but he will remember how Ma depended on him.

One of the deficiencies of “Room,” and there are not many, is that several important revelations must be spoken by Ma. From the beautiful visuals of “Cast Away,” we know exactly what has happened to Tom Hanks. “Room” feels obligated to deliver a backstory that perhaps doesn’t require as much explanation as director Lenny Abrahamson provides.

Another drawback is the cliché portrayal of an insensitive TV personality who pushes the heroine past the breaking point. Her damning question, if suggested at all, would far more likely be offered in the form of a public service announcement separate of the interview. (Whether a male or non-mother could be charged for leaving a baby at a firehouse is a good question.)

It is strongly implied that Ma’s tragedy will be exploited by the media, lawyers and PR handlers. Why she supposedly needs money is not clear. “Room” sells society short in its ability to look out for someone.

It is suggested that the perpetrator would fight the charges. What would possibly be the defense? Old Nick would presumably make a Symbionese Liberation Army-esque argument, that Ma agreed to join him and remain “missing” from society. While movies are capable of anything, this one can’t bring itself to believe Old Nick might actually walk.

Guilt and stigma will follow Ma and Jack for life. Those don’t have to be deal-breakers. “Room” informs us that where we come from isn’t nearly as important as where we’re going.

4 stars

(November 2015)

“Room” (2015)

Starring Brie Larson as

Ma ♦

Jacob Tremblay as

Jack ♦

Sean Bridgers as

Old Nick ♦

Wendy Crewson as

Talk Show Hostess ♦

Sandy McMaster as

Veteran ♦

Matt Gordon as

Doug ♦

Amanda Brugel as

Officer Parker ♦

Joe Pingue as

Officer Grabowski ♦

Joan Allen as

Nancy ♦

Zarrin Darnell-Martin as

Attending Doctor ♦

Cas Anvar as

Dr. Mittal ♦

William H. Macy as

Robert ♦

Jee-Yun Lee as

News Anchor ♦

Randal Edwards as

Lawyer ♦

Justin Mader as

FBI Agent ♦

Ola Sturik as

Reporter #1 ♦

Rodrigo Fernandez-Stoll as

Reporter #2 ♦

Rory O’Shea as

Reporter #3 ♦

Tom McCamus as

Leo ♦

Kate Drummond as

Neighbor ♦

Jack Fulton as

Jack’s Friend

Directed by: Lenny Abrahamson

Written by: Emma Donoghue (novel, screenplay)

Executive producer: Jeff Arkuss

Executive producer: Ross Garnett

Executive producer: Andrew Lowe

Executive producer: Tessa Ross

Executive producer: Jesse Shapira

Executive producer: Andrew Lowe

Supervising producer: Chantel Kadyschuck

Producer: David Gross

Producer: Ed Guiney

Line producer: Hartley Gorenstein

Music: Stephen Rennicks

Casting: Robin D. Cook, Fiona Weir

Cinematography: Danny Cohen

Editing: Nathan Nugent

Production design: Ethan Tobman

Art direction: Michelle Lannon

Set decoration: Mary Kirkland

Costume design: Lea Carlson

Makeup and hair: Sid Armour, Joan Chell, Stacey Butterworth

Stunts: Jean Frenette, Jean-Francois Lachapelle

Special thanks: Victoria Owens