‘Once Upon a Time’ makes a call on Hollywood’s Worst Day

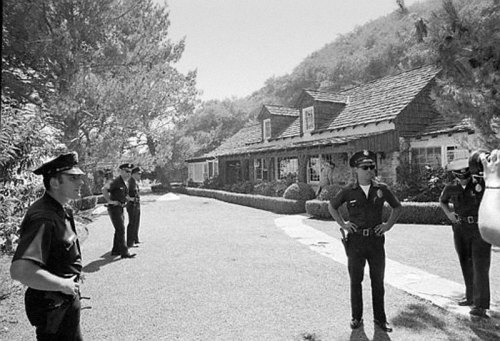

What is Hollywood’s Worst Day? It quite possibly is the murder of Sharon Tate in the very early hours of Aug. 9, 1969. Four other people who were not moviemakers were slain at that house, but it’s the butchering of the pregnant Tate, a New Hollywood actress at 26, that shocked the world, a public trauma that only intensified over months as the killers, for a short while, somehow were getting away with it.

It kind of feels like they still are. Charles Manson reached age 83 spouting venom from prison. He and the still-living members of his gang, though permanently incarcerated, have experienced decades of pop-culture notoriety for one of America’s most senseless and unforgivable crime sprees.

If only someone could’ve stopped ’em ...

Quentin Tarantino’s “Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood” is desperately trying to tell us something he has undoubtedly believed for a very long time — that there is something special or significant about the year 1969, at least as experienced in Southern California.

Many born in the ’60s or ’50s will tell you he’s right. But what is that “something”? “Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood” never quite figures it out.

It’s a film of beautiful but incomplete sentiment. Incomplete, despite running 161 minutes, an eye-opening indulgence — “wasteful self-indulgence,” according to Rex Reed — of even an acclaimed director.

A few red flags are evident. According to reports, Tarantino conceived the idea back in 2009; any film concept that takes 10 years to get finished is, almost unfailingly, a dubious one. The movie was released just in time for the 50th anniversary of the Tate-LaBianca murders. Anniversary films tend to do little more than re-create and mark time.

Leonardo DiCaprio is an extraordinary film actor. He is also extraordinarily boyish-looking, a characteristic that was ideal for “Titanic” but should’ve nullified his casting as Rick Dalton. Rick’s career path suspiciously seems to mirror that of Clint Eastwood, except that when Rick gets sent to Europe, he comes back with little more than a wife. (Which also calls into question the static, tiresome opening conversations with Al Pacino’s shady casting exec Marvin Schwarz, whose most memorable line is the pronunciation of his name, “Schwars” (not “Schwartz”).)

They say that movies about the past tend to be even more about the present. Tarantino’s film suggests Hollywood is a tough business, serving a fickle public that crowns stars and then discards them. That isn’t a new idea. It also strongly suggests, as does Sofia Coppola’s convincing works of “The Bling Ring,” “Lost in Translation,” and “Somewhere,” that even famous Hollywood figures lead uninteresting or unrewarding lives filled with the daily grind of Average Joe. The money is concentrated at the top, barely trickling down to the heroic support staff who live in shacks near drive-in theaters, while any fame is rapidly fleeting for anyone not on a marquee or on this week’s cover of TV Guide.

So Rick is a victim of a cutthroat industry. Well, maybe not. Tarantino quietly suggests that maybe Rick’s star is fading because of Rick. He drinks too much and takes work for granted and feels sorry for himself. Yes, he’s a capable performer, but he’s expecting success to come to him. He has a heart, but it’s not connected to anything that matters.

Eventually, he will find himself a real hero, but a fluky one. That’s an homage to much farther back than 1969; Vincent Price, for example, did it in the playful 1951 Robert Mitchum-Jane Russell noir “His Kind of Woman.”

Cliff Booth, Rick’s aging gofer, easily grasps the Pavlovian world that most his age should’ve long graduated from — keep doing things for important people, and they’ll (barely) take care of you. Brad Pitt’s happy-to-be-here typecasting keeps him out of lead roles but serves him well as Cliff, whose backstory is delivered like the shrapnel that his life has become. Tarantino seems to be saying, There’s an infrastructure here of Cliffs, people who seem to do all the right things even though there are rumors they’ve done very bad things; hence, look where Cliff lives.

Rumors about an actor are one thing; rumors about a stuntman seem like a strange plot device. Tarantino needs to justify how someone as impressive as Cliff has come to find himself in such a groveling position rather than commanding premium dollars for working on Steve McQueen films. It’s a curious 180 from another movie about a stuntman, Burt Reynolds’ “Hooper,” which is not a great movie but draws a much more convincing portrait, like Mickey Rourke in “The Wrestler,” of a battered entertainer who should move on to another career but thrives on the adrenaline of his profession. For Cliff, there is no adrenaline. “Hooper,” 1978, was directed by Hal Needham, acclaimed as the greatest stuntman of all time, and much of Burt Reynolds’ portrayal feels authentic. Cliff feels a lot less authentic and more like someone borrowed from those Marvel movies. Then again, that’s probably a necessary persona for saving Sharon Tate, something Sonny Hooper would look out of place doing.

In “The Electric Horseman,” we see how a broken-down star of roughly Rick and Cliff’s age, one who has a drinking problem, becomes tired of his spiral and then is suddenly inspired, by a horse, to break free of it. Rick and Cliff are relegated to little more than a moment of self-defense that probably wouldn’t meet Neighborhood Watch standards.

What do Rick and Cliff have to do with Sharon Tate? Not enough, except a contrast. On the arc of stardom, she is at the beginning, Rick and Cliff are a lot closer to the sunset. “Once Upon” assumes that viewers know who Tate was. In this film, she is not even what Roger Ebert always called a macguffin; the people around her who will play crucial roles in this story are largely oblivious to her.

Unlike Rick, whose obligations as an actor are painfully depicted in erratic sprees of awkward flashbacks and conversations, Margot Robbie’s Sharon enjoys the A-list without any effort. Tarantino found so little use for her background that he shows her having nothing to do. She watches one of her own movies at a theater, only after first struggling to convince the staff that she really is one of the actresses in the film. This Sharon Tate is far less an actress than a gene-pool champion, marveling not at her own assets but remarkable fortune.

And right there is the heart of this film: Tarantino’s steep admiration for humankind’s lottery winners and the sense of tragedy when they are deprived of their destiny. It’s an affirmation that we can’t be Sharon Tate or John Lennon or JFK or even Rick Dalton but that we win when they get to do what they do. The possibility of a random person’s intervention prior to a tragedy serves as the conflict in “Once Upon,” to be settled at Rick Dalton’s pool.

The strongest characters, unfortunately, are the Family members. We see childlike innocence lightly concealing a criminal and psychopathic enterprise. Margaret Qualley, whose presence seems a nod to the pretty girl in “Save the Tiger,” is a harmless peace-and-love type ... or the devil incarnate. Cliff’s stroll (and it is a tedious one) through the Spahn Ranch gradually draws a crowd of menacing youngsters who encircle him and stare at him as though we’re entering a bona fide horror movie. There is beautiful ambiguity here in the faces — they don’t quite look like cultists, nor are they revolutionaries, nor hippies, nor typical stoners, nor slackers; they straddle all of the above. Then they stand by helplessly as Cliff maims one of their own, and it’s hard to take them so seriously.

The Spahn Ranch sequence must be deemed, at best, a missed opportunity. On the surface, it’s a beautiful parallel — George Spahn and Rick Dalton made great careers out of TV Westerns; now it’s an industry in shambles. Rick Dalton can still overcome or sidestep this momentum; George Spahn is long past that point. Tarantino wants to believe that there is something significant about the Manson family living in a former television site. He fails to show it. Would it matter if they lived at an old car dealership or abandoned campground? No. They’re somewhere off the grid, where they can get away with ordinance violations and small crimes and even one of the crimes of the century (until they started talking about it).

And would it matter if Cliff had not visited the ranch to check on George Spahn? No again. Cliff’s encounter with Manson family members supplies nothing for the film’s conclusion other than a mediocre living-room punch line. The three people Cliff deals with at the ranch — Pussycat, Squeaky Fromme and Clem — are not present in the climax. Worse, Cliff’s trip to the Ranch hints at a couple possibilities that detract from the plot — it’s implied that Cliff could well be motivated to notify police to investigate the ranch and preempt the murder spree, or that family members might’ve set their sights for revenge on the home where Rick’s car is parked, rather than taken aim at the house next door.

Setting a mood, Tarantino repeatedly stalls. His characters, prior to that night in August, are in pop culture Disneyland, but there’s nothing for them to do. “American Graffiti,” a film made about a decade later than its setting, showed us burger joints and sock hops and drag racing. “Once Upon a Time” shows us movie posters. That’s not a bad start, especially at a time when some were still designed impressively like comic-book covers, a lost art today, but it’s not 161 minutes of movie. One reviewer notes the “curiously inert” pace especially early, “with a lot of time spent in cars with the characters as they drive around and around.”

Actually, these characters spend far more time at TV production sets than in their cars. Roger Ebert once noted “a movie set is one of the most boring places on earth most of the time.” Not so boring are movie stars’ homes. Ebert marveled at the set used for “Mommie Dearest.” Tarantino has such an opportunity to wow and dismisses it. Tate and Polanski were not as wealthy as Joan Crawford but were two of the world’s hippest people in 1969. Whatever their home looked like is interesting. This film could’ve offered something fascinating and respectful much unlike the morbid interest with Sharon Tate crime scene photos. But Tarantino uses their tragic residence, as well as Rick Dalton’s, as little more than a movie poster stand. Do most Hollywood stars decorate their homes with movie posters, specifically posters of their own work? That’s a good question.

The director didn’t sweat the smaller details that others obsess over. The Chicago Sun-Times front-page story of Sunday, Aug. 10, 1969, points out fairly quickly that Tate “was dressed in a bikini-type nightgown, police said.” The Chicago Tribune reported that weekend that Tate was “clothed in bikini panties and brassiere.” (The Sun-Times article says the Tate home was worth $200,000 and that police were called shortly after 9 a.m. on the morning of Aug. 9 by a caller who said, “You better get a police car over here right away. There’s a man lying on the front lawn and blood all over the place. It looks like a bad one.”)

Tarantino to many is an auteur. Others aren’t so convinced. The critical and industry consensus, however, favors him enough to trumpet “Once Upon a Time” as his “9th film” (that’s counting the “Kill Bill” installments as one movie), a numerical distinction not accorded to Steven Spielberg or Spike Lee, or, off the top of the head, possibly no one else. (Quick: Name Orson Welles’ ninth film.) As a tribute to Hollywood, “Once Upon” has decent Oscar prospects. “Pulp Fiction,” “Inglourious Basterds” and “Django Unchained” all received best picture nominations, though none won the big prize.

“Once Upon” cannot be considered autobiographical, despite the fact critics such as USA Today’s Barbara VanDenburgh describe it as a “personal and self-reflective film about aging and the inevitability of creative obsolescence.” Tarantino’s signature work will forever be “Pulp Fiction” and best may well be “Jackie Brown,” but his ability to channel his own youthful appreciation of the charms of cinema to today’s audiences remains undiminished. At 56, he might even top his previous all-time-high grosser, “Django Unchained.”

“Once Upon” correctly senses that there is something fascinating about 1969. What’s odd is that Tarantino seems to think the only thing fascinating about it was watching a movie. It’s a year in which we got not only a moon landing and Woodstock and Chappaquiddick but polarizing holdovers in the Vietnam War and Richard Nixon, typical clichés that Tarantino spurns, which is probably admirable, but he doesn’t have anything to fill in the gaps, and this is a pop-culture movie. Think about who was on the planet in 1969. The people in their 40s weren’t Gen-X’ers; they were veterans of Midway, Iwo Jima, Omaha Beach. Rebellion was semi-mainstream; clothing was undergoing massive alteration. A lot of adults still wore suits to ballgames and barely knew what narcotics were. Laurence Olivier, John Wayne, Elizabeth Taylor, Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda and, if he hadn’t just retired, Cary Grant, were still box-office titans. Bill Russell captained the Celtics, Mays and Aaron patrolled the outfield, Mantle had just called it quits. There was no designated hitter. Unitas quarterbacked the Colts with a crew cut. Arnold Palmer had a few wins left.

There are only a couple of very faint references to Vietnam and Robert Kennedy. What speaks much louder in this film is a greater sense of innocence and a lesser sense of regulation, much like “American Graffiti,” though that film didn’t spotlight drug use. People would pick up hitchhikers and not expect to be murdered. People didn’t care about wearing seat belts. You didn't need to display an ID to stay at a motel. You could volunteer for organizations without submitting to a background check. You could, as some Southern California celebrities did, let strangers hang out at your home. The concerns around all of those activities have unfortunately become much more elevated, for what sadly are very good reasons.

The Hollywood that Tarantino recalls here is the Hollywood with a moat. To see a film, you went to a theater, perhaps a drive-in. It was, and still is, a community experience. Buying a ticket gave you entree to the pop culture conversation. No streaming, no HBO, no VCRs/DVDs, no video games, no Facebook, no cellphones to encroach upon the experience. Print media as well enjoyed a rock-solid niche. If you wanted multiple reviews of “Don’t Make Waves,” you didn’t click on Rotten Tomatoes. It took work. You found copies of The Hollywood Reporter, Variety, The New Yorker, Village Voice, The New Republic, maybe Time or Rolling Stone, or national editions of The New York Times, Washington Post, Chicago Sun-Times or Los Angeles Times, all chock-full of advertising. There was not diffusion of media but an Establishment, one whose limited offerings were considered a treat.

Critics have long detected a theme of aging concerns in Tarantino’s work. The prime example is “Jackie Brown,” people at or beyond middle age finding themselves invigorated by an unexpected challenge. It feels like this director believes humans are locked in a losing battle against time, that whatever good we’ve got today will be gone tomorrow, in the same way that a million dollars in 1919 was worth far more than a million dollars in 2019.

Hollywood has had other cause for solemnity. Among other tragedies, there was Carole Lombard’s plane crash, James Dean’s car crash, Marilyn Monroe’s pills and Natalie Wood’s boat, which appears to interest Tarantino in this film (and doesn’t mesh at all with 1969). Those people were all more famous than Tate. There was the 1982 “Twilight Zone” helicopter tragedy that killed Vic Morrow and child actors Myca Dinh Le and Renee Shin-Yi Chen. Maybe Hollywood’s darkest hour was the Blacklist and the Hollywood Ten, but that took years, not a single day, and was defended by the likes of Walt Disney, Ronald Reagan, John Wayne and (eventually) Humphrey Bogart and was still polarizing when Elia Kazan was honored at the 1999 Oscars.

Debra Tate (left) and Steven Parent’s sister, Janet (right), and others hold hands

prior to the announcement of the decision at Susan Atkins’ 2000 parole hearing.

Sharon Tate, like Amelia Earhart, is almost surely famous today because of how her life ended. (Tarantino curiously implies through her theater visit that she did not yet stand out in Hollywood.) There are certain landmark news events still regarded to this day with considerable national pain, for reasons both obvious and unquantifiable. Tate was not JFK or MLK or RFK, but her death is traumatic to the national, and global, conscience, a horrifying revelation of what human beings are capable of doing. The what-if for an actress is not the same as for a president, but it haunts us. Imagine if JFK had made that speech at the Trade Mart, if MLK had departed Memphis for another rally, if RFK had headed on to Chicago and won there, if John Lennon had parked a few security guards at the Dakota entrance, if all those people at the World Trade Center, Pentagon and on the planes could’ve just awakened and gone to work on 9/12.

Motivation of the Manson Family was semi-officially decreed by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi as a strange plot to launch the world into some sort of “Helter Skelter” apocalypse in which Manson would emerge triumphant. Some Family members and observers have claimed the cause of the Tate-LaBianca murders was more practical, to disrupt the police case against Family members in the July ’69 murder of Gary Hinman, a Family acquaintance, by doing copycat killings of complete strangers so police would think Hinman’s killer was still at large.

“Once Upon a Time,” interestingly, suggests a third and different motivation behind that horrific weekend — one rejected by the real Roman Polanski, sitting next to Sharon Tate on Hugh Hefner’s Playboy TV show in February 1969. Tarantino depicts Family members in the car on Cielo first agreeing that they were told to attack 10050, then, after noting Rick Dalton lives in the cul-de-sac, deciding instead to go along with the Susan Atkins character’s idea that in the ’50s, “Every show on TV that wasn’t ‘I Love Lucy’ was about murder. So, my idea is, we kill the people who taught us to kill.” Polanski told Hefner several times some variation of, “I do not believe that any violence on television or cinema screen can inspire violence.”

“Once Upon a Time” gently dabbles in hopeless revenge fantasy, as if anyone could somehow do more to these monsters than they did to us. Only one person really comes close — not Rick Dalton, but another kind of hero, Debra Tate, Sharon’s sister. Their mother publicly fought until her own death in 1992 to keep the Family jailed. Now, as parole boards have gradually started to endorse some of these aging inmates, it’s Debra who shows up at every one of those hearings and perhaps singlehandedly keeps these perpetrators from something they couldn’t have cared less about at 10050 Cielo Drive but you know they very much want — a little freedom in old age.

The ending. Think for a moment if “Once Upon a Time” began with the final scene instead of concluding with it. Tarantino could still deliver his beautiful shots of 1969. Sending Rick to auditions for “Love, American Style” and perhaps “The Towering Inferno” would be entertaining, sure. Casting Sharon in new roles as a mom, speculating on her marriage to Polanski, sadly, no. Something about that just doesn’t feel right.

3 stars

(September 2019)

(Updated May 2022)

(Updated July 2024)

“Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood” (2019)

Cast:

Leonardo DiCaprio

as Rick Dalton

♦

Brad Pitt

as Cliff Booth

♦

Margot Robbie

as Sharon Tate

♦

Emile Hirsch

as Jay Sebring

♦

Margaret Qualley

as Pussycat

♦

Timothy Olyphant

as James Stacy

♦

Julia Butters

as Trudi

♦

Austin Butler

as Tex

♦

Dakota Fanning

as Squeaky Fromme ♦

Bruce Dern

as George Spahn ♦

Mike Moh

as Bruce Lee ♦

Luke Perry

as Wayne Maunder ♦

Damian Lewis

as Steve McQueen ♦

Al Pacino

as Marvin Schwarz ♦

Nicholas Hammond

as Sam Wanamaker ♦

Samantha Robinson

as Abigail Folger ♦

Rafal Zawierucha

as Roman Polanski ♦

Lorenza Izzo

as Francesca Capucci ♦

Costa Ronin

as Voytek Frykowski ♦

Damon Herriman

as Charlie ♦

Lena Dunham

as Gypsy ♦

Madisen Beaty

as Katie ♦

Mikey Madison

as Sadie ♦

James Landry Hébert

as Clem ♦

Maya Hawke

as Flowerchild ♦

Victoria Pedretti

as Lulu ♦

Sydney Sweeney

as Snake ♦

Harley Quinn Smith

as Froggie ♦

Dallas Jay Hunter

as Delilah ♦

Kansas Bowling

as Blue ♦

Parker Love Bowling

as Tadpole ♦

Cassidy Hice

as Sundance ♦

Ruby Rose Skotchdopole

as Butterfly ♦

Danielle Harris

as Angel ♦

Josephine Valentina Clark

as Happy Cappy ♦

Scoot McNairy

as Business Bob Gilbert ♦

Clifton Collins Jr.

as Ernesto The Mexican Vaquero ♦

Marco Rodríguez

as Bartender on Lancer ♦

Ramón Franco

as Movie Theater Manager ♦

Raul Cardona

as Bad Guy Delgado ♦

Courtney Hoffman

as Rebekka ♦

Dreama Walker

as Connie Stevens ♦

Rachel Redleaf

as Mama Cass ♦

Rebecca Rittenhouse

as Michelle Phillips ♦

Rumer Willis

as Joanna Pettet ♦

Spencer Garrett

as Allen Kincade ♦

Clu Gulager

as Book Store Man ♦

Martin Kove

as Bounty Law Sheriff ♦

Rebecca Gayheart

as Billie Booth ♦

Kurt Russell

as Randy ♦

Zoë Bell

as Janet ♦

Michael Madsen

as Sheriff Hackett on Bounty Law ♦

Tim Roth

(scenes deleted) ♦

Perla Haney-Jardine

as Hippie Selling Acid Cigarettes ♦

James Remar

as Ugly Owl Hoot on Bounty Law ♦

Monica Staggs

as Connie ♦

Craig Stark

as Land Pirate Craig ♦

Keith Jefferson

as Land Pirate Keith ♦

Omar Doom

as Donnie ♦

Kerry Westcott

as Dancer ♦

Kate Berlant

as Bruin Box Office Girl ♦

Victoria Truscott

as Musso & Frank Hostess (Gina) ♦

Allison Yaple

as Lancer Script Girl ♦

Bruce Del Castillo

as Back Lot Crew Member ♦

Brenda Vaccaro

as Mary Alice Schwarz ♦

Daniella Pick

as Daphna Ben-Cobo ♦

Lew Temple

as Land Pirate Lew ♦

David Steen

as Straight Satan David ♦

Mark Warrick

as Curt ♦

Gabriela Flores

as Maralu the Fiddle Player ♦

Heba Thorisdottir

as Make-Up Artist Sonya ♦

Breanna Wing

as Young Girl Hippy Hitchhiker ♦

Ken ‘Sonny’ Donato

as Musso & Frank Bartender ♦

Casey O’Neill

as Nazi Soldier / McCluskey Burn Nazi #1 ♦

Michael Graham

as Officer ♦

Emile Williams

as Paramedic ♦

Vincent Laresca

as Land Pirate Vincent ♦

JLouis Mills

as Land Pirate J ♦

Maurice Compte

as Land Pirate Maurice ♦

Gilbert Saldivar

as Land Pirate Gil ♦

Eddie Perez

as Land Pirate Eddie ♦

Hugh McCallum

as Lancer Camera Operator Hugh ♦

Zander Grable

as Hermann The Nazi Youth ♦

Ed Regine

as Cicada Maitre’d ♦

Michael Bissett

as Officer Mike ♦

Lenny Langley Jr.

as Dashihi Donnell ♦

Gillian Berrow

as Gillian ♦

Chad Ridgely

as Cop #1 ♦

Chic Daniel

as Cop #2 ♦

Inbal Amirav ♦

Corey Burton

as Bounty Law Promo Announcer (voice) ♦

Tea Jo

as Hippie ♦

Michaela Sprague

as Dancer

Directed by: Quentin Tarantino

Written by: Quentin Tarantino

Producer: Quentin Tarantino

Producer: David Heyman

Producer: Shannon McIntosh

Executive producer: Jeffrey Chan

Executive producer: Dong Yu

Executive producer/line producer: Georgia Kacandes

Associate producer: William Paul Clark

Associate producer: Daren Metropoulos

Cinematography: Robert Richardson

Editing: Fred Raskin

Casting: Victoria Thomas

Production design: Barbara Ling

Art direction: Richard L. Johnson, John Dexter, Jann K. Engel, Helena Holmes, Eric Sundahl

Set decoration: Nancy Haigh

Costumes: Arianne Phillips

Stunts: Casey Adams,

Robert Alonzo,

Daniel Arrias,

Steven J. Bagnara,

Matt Baker,

Zoë Bell,

Hannah Betts,

Joey Box,

Damien Bray,

Bob Brown,

Brian Brown,

Tamiko Brownlee,

Joe Bucaro III,

Bryan Cartago,

Cue Chatley,

Cecile Cubilo,

Clay Cullen,

Cory DeMeyers,

Mike DeMille,

Gary Dionne,

Mark Dobson,

Brian Duffy,

Seth Duhame,

Zack Duhame,

Nash Edgerton,

Peter Epstein,

Charlie Estepp,

Stephane Feruch,

Travis Fienhage,

Jeremy Fitzgerald,

Ken Gilbert,

Riley Harper,

Jimmy Hart,

Cassidy Hice,

Dylan Hice,

Toby Holguin,

Jacob Horn,

Lisa Hoyle,

Keith Jardine,

Adam Jeffrey,

Ralf Koch,

Rick Lange,

Tony Lazzara,

Samuel Le,

Tara Macken,

Braxton McAllister,

Michaela McAllister,

Ed McDermott II,

Mike McKee,

Norman Mora,

Mike Mukatis,

Kimberly Shannon Murphy,

Casey O’Neill,

Allan Padelford,

Jim Palmer,

Dario Perez,

Eddie Perez,

Dana Reed,

Dalton Rondell,

Eric R Salas,

Wesley Scott,

Jason Tubbs,

Christian Van Fleet,

Karl Van Moorsel,

Mark Aaron Wagner,

Marcus Young,

Glen Yrigoyen