‘Future’ in flux: Maybe we don’t

have the capacitor to change

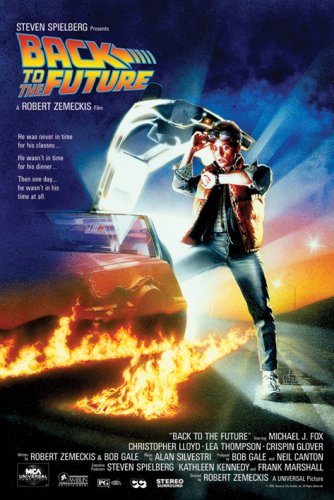

“Back to the Future” reminds us of one of filmdom’s greatest messages: We’re all meant for our time. But it espouses at least two other themes. Both cannot be correct.

One is that people can change. It is embodied by George McFly. The suggestion is that if we can identify our mistakes and our limitations, we can correct them and improve ourselves.

The other theme is that we don’t change. That life has chosen a path for us and we’re just along for the ride. This is also presented, in cinematic irony, through George McFly. Despite this massive interruption into his life by a futuristic person, leading to a significant amount of personal growth, he ultimately ends up with the same result as before. Same wife, same children, same home, just a higher-paying, more prestigious occupation.

Consider the logical pickle we’ve got here. If we believe the first notion, that people can change, then why is George’s change so fluky? His son, try as he might, does not cause George to change. It is only after his son has thrown in the towel and created an artificial scheme that George realizes his own ability to stand up for himself. We see Marty, inadvertently, adjusting fate. Lorraine originally fell for George for a bad reason, the “Florence Nightingale Effect.” Because of Marty’s interference, she ultimately falls for George for a much better reason: he bravely defended her in a bad situation. George changed only because of random, unplanned events. Which leads us to the polar opposite analysis, that George (or any person) is no more master of destiny than a lab rat is, that his life’s course is set in stone no matter how many times Marty interrupts it, and that lesser issues such as wealth and prestige and confidence are determined by chance.

Maybe the purest theme of “Future” then would be “having it both ways.” It doesn’t take a physicist to note the absurdities such as half-faded photographs. But there is a very convincing story told here that we’re dying to believe. It is a beautiful role-reversal of a child meeting his parents at the same age but able to serve as the grownup who knows better, because in this case he does.

The latter is doable in a standard film if the child is in his or her 50s or 60s and, for example, might have to take care of a parent (such as in “Monster’s Ball”). One delight of “Future” is that Marty gets to be the same age as his parents, only far wiser to the ways of the world.

One preconception is that Marty is simply better than his parents. Marty stands up for himself and doesn’t take Biff’s gruff. We see this in 1955 and both versions of 1985. Marty believes in science and is willing to give it a chance, to take a risk, to explore, while George won’t even let anyone see his writings. Marty has a beautiful girlfriend while George is reduced to peeping-tomness.

One message is clear: Life is about exploring, being assertive and collecting the rewards from it. We are either going to be Biff’s employee or employer. (We are also led to believe that a single punch converted Biff from bullying to subservient.) Marty is smart & savvy; he could’ve been cautious upon his arrival in 1955, but he aggressively searched for answers, and while that caused him considerable short-term difficulties, everyone came out for the better in the end.

A major statement is made in Marty’s siblings. When dad is a loser, the son works at McDonald’s. When dad is a winner, the son wears a suit to the office. Notice, though, there is no change in Marty between the two worlds, a logical flaw we must accept and overlook.

While correctly designated as sci-fi, “Future” actually has much in common with the spree of famous teen-angst movies of its time. Marty, like the teens in “The Breakfast Club” or “Ferris Bueller,” is a high school student who's having serious issues with his parents. Unlike in those other movies, he can actually fix them before they start. That’s science.

This is a Robert Zemeckis film fronted financially by Steven Spielberg. Like many but not all Spielberg works, it is heavier on pizzazz than story. Zemeckis clearly likes the car and the flux capacitor. He likes the discomfort between Marty and his teenage parents. He does very well with those concepts.

Straying beyond that, the results are dicier. To his credit, Zemeckis takes a thought-provoking dip into rewriting the 1950s, as seen on TV.

Cinema, even to this day in films such as “Doubt,” tends to regard the JFK assassination as the dividing line between Happy America and Disturbed America. In the ’50s, we didn’t have problems with drugs, alcohol, divorce or social concerns such as civil rights, gay rights or war protests.

Or so we’ve often been made to feel.

Zemeckis jabs at those notions — slightly. He shows that a typical 1955 family had very 1980s-ish concerns. We learn that Lorraine likes to drink and smoke, that her brother will become a career criminal, that George is something of a pervert, that people did smoke pot.

Zemeckis twice makes a statement about African Americans. One is about a diner busboy in 1955 envisioning he could someday become mayor. We already know that will happen, and that the mayor in question seems a bit of a flake. Dreams of being a scientist apparently would be too serious for this film. Then there is the curious matter of the Marvin Berry band.

The goal here is to add to Marty’s hipness credentials. The results are poor; first (blatantly) that the black band members are the only people in the film on pot, and second (inadvertently, perhaps) that Chuck Berry is learning a “new sound” from a suburban white kid of Hill Valley.

When it comes to women, Zemeckis is stuck in 1955. George is given the opportunity to change, not Lorraine. Her fortune, it is clear from both versions of 1985, is strictly dependent on how George turns out. Jennifer, Marty’s impressive girlfriend, is left out of the 1955 sequence and serves as little more than momentary eye candy. Her on-screen time at the beginning is so limited, we have no reason to long to return to her as Marty does.

There was a simple way to work Jennifer into 1955. Zemeckis could’ve placed her with Marty and Doc at the mall just as the Libyans arrived. Eventually, time travel with Jen will happen in the two sequels. But in this movie Zemeckis clearly decided that would be too complicated. That was likely the correct call. Jen’s character would presumably want to look up her own parents and wonder about her own past, and her presence would limit screen time for Biff and Doc.

There should be no gripes about the car. Its presence is smartly limited. It could’ve been shown more often, running circles around Biff and his gang for example. That likely would’ve only watered down its appeal. The car exemplifies the future: very mysterious, very powerful, subject to serious breakdown. The film’s best scene is the ending, where Doc fuels the car with garbage rather than the much-much-trickier plutonium (scientific progress that someday probably will be realized) and closes with the unforgettable line about roads (so famous, it was used by Ronald Reagan in the 1986 State of the Union address and made the Widescreenings.com “Famous movie quotes” page).

This film, proof that even movies about the future can appear dated, is one of at least two major releases of the 1980s to use Libyans as bad guys (“Broadcast News” is another, albeit in a more objective journalistic stance).

So much written already, with not even a nod yet to the actors. That should not be taken as a slight.

A winning performance is delivered by Michael J. Fox. The landmark work is by Christopher Lloyd.

Neither Lloyd nor Fox received an Oscar nomination. Fox did receive a Golden Globe nomination. It is the opinion of this site that Lloyd’s work is a strong contender for best supporting actor of all time.

The mad or eccentric scientist type of character is probably not all that difficult. What Lloyd inserts is heart. He can demonstrate the value of science and reverence for it while acknowledging the importance of a love story. He is single apparently for life and shows little interest in social relationships. When Marty arrives with this gift of a car, Doc’s scientific impulses should take over. Keep the DeLorean, figure out a way to get the plutonium or equivalent and get a 30-year head start on his own project. Eventually it’ll work and then Marty can go back.

That would be cold. Zemeckis’ way around this is for 1955 Doc to already possess severe don’t-tinker-with-the-past beliefs. This could be a matter of self-preservation (more on that below), but it’s more than that, as Doc stresses this point before knowing any of the extent of Marty’s involvement in town life and realizing Marty is at risk.

This seems slightly at odds with Doc’s goals at the beginning of the film. One wonders, shouldn’t Marty and young Doc be sitting around in 1955 thinking, what can we do to make the world a better place? Doc has reason to believe, thanks to Marty’s presence and 1985 video, that things have turned out OK for him and presumably the world. But Marty knows better, it doesn’t happen without tragedy and loss. Fox isn’t allowed to even ponder this out loud. Could he warn the government about Sputnik, Oswald, Castro, Vietnam; send a tip to people like Buddy Holly, Patsy Cline, James Dean (who died in September 1955 as a matter of fact)? Those kinds of thoughts are too deep for this film; they are never entertained.

Nevertheless, Doc makes, very implicitly, a warm statement on the importance of “keeping it real,” or not artificially interfering with the course of human ups and downs. This is somewhat at odds with a statement made in another thought-provoking time-travel film, “The Final Countdown,” 1980, starring Kirk Douglas and Martin Sheen on an aircraft carrier that can defeat the attack on Pearl Harbor. Apply logic to this, and it seems preserving dubious history is not such a lofty or even rational goal. The bigger picture is that characters are allowing the future to be determined by the successes and mistakes of humans, not machines — a typical triumph in sci-fi.

Or, in a less-altruistic way, it could be simple self-preservation. Not only is Marty’s existence threatened. Maybe Doc realizes, driving around the DeLorean in 1955, he could end up in a crash and never see 1985 or even 1956. This concept seems to flunk the logic test. It never occurs to the characters, for example, that Doc could simply allow Marty to pass away before lightning hits, then drive the car himself and program it one week back, so that he could intercept Marty’s arrival and prevent the meddling that eventually (almost) dooms Marty?

Of course, then there would be two cars, two Martys, two Docs, all in the same scenes, a scientific quagmire this film clearly does not aspire to.

So we get the illogical “have it both ways” outcome, where it’s deemed wrong to alter the past or future unless Doc is about to get shot.

Lloyd cements the affection for his character with two smiles. One is when he figures how to connect the wires just before leaping from the clock tower. The other is when he shows Marty his bullet-proof vest.

Fox was 24 when the film was released, playing a 17-year-old. He does this without a hitch, being well-prepared for the assignment by his previous years’ work on “Family Ties.” According to Wikipedia, Fox was the natural choice for Marty but was unable to shoot the film around his TV schedule, so Eric Stoltz got the part. But Stoltz wasn’t deemed right, so a renewed effort secured Fox, who is highly regarded for his loyalty to his sitcom “family” during and after his movie sensation.

The obvious concern with putting TV stars in movies is that they are long-since typecast and won’t work in a fresh setting with big dollars on the line. Fox is remarkable in that Marty McFly is just as effective as Alex P. Keaton despite the fact they’d never be friends. Marty is careful to be apolitical and not to sound too conservative, but there are moments, such as when he declares the president is Ronald Reagan, where it feels a tiny bit like this is Alex P. Keaton speaking.

The movie required a lot more action from Fox’s character than “Family Ties” viewers would expect. According to credits, Fox’s stunt double was Charlie Croughwell.

A couple scenes could be better. Probably the worst moment in the film is when “Darth Vader” scares George in the middle of the night into asking Lorraine out. The discovery of the lightning-strike pamphlet is awkward, when Doc asks Marty “is she pretty” and Marty is prompted to pull out the sheet of paper.

Like “JFK,” “Goldfinger” and a few select others, “Future” has a scene where characters look over a scale-model or near-scale-model of a geographic area to plan or explain an operation.

Time travel is one film subject fraught with too much possibility. Willful Suspension of Disbelief must be employed, but the results can be glorious, as in this film and others such as “The Terminator.” The values of “Future” are suspect, the logic sometimes unfathomable. Yet it remains one of the most watchable films of the ’80s and of the sci-fi genre. Marty helped his parents and defeated Biff. Doc got an early look at his grand invention. This is not particularly deep material. Somehow it works.

Maybe more than anything, it reminds us, as does “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” that no matter how intrigued we are by the future or nostalgic for the past, we belong right where we’re at, in the present. The 1980s suburban shopping mall doesn’t seem like a most glorious destination — until you’ve been stuck for a week in a different decade, with your parents no less. Rarely has a JCPenney ever looked so appealing.

4 stars

(September 2009)

“Back to the Future” (1985)

Starring Michael J. Fox as Marty McFly ♦ Christopher Lloyd as Dr. Emmett Brown ♦ Lea Thompson as Lorraine Baines McFly ♦ Crispin Glover as George McFly ♦ Thomas F. Wilson as Biff Tannen ♦ Claudia Wells as Jennifer Parker ♦ Marc McClure as Dave McFly ♦ Wendie Jo Sperber as Linda McFly ♦ George DiCenzo as Sam Baines ♦ Frances Lee McCain as Stella Baines ♦ James Tolkan as Mr. Strickland ♦ Jeffrey Jay Cohen as Skinhead ♦ Casey Siemaszko as 3-D ♦ Billy Zane as Match ♦ Harry Waters Jr. as Marvin Berry ♦ Donald Fullilove as Goldie Wilson ♦ Lisa Freeman as Babs ♦ Cristen Kauffman as Betty ♦ Elsa Raven as Clocktower Woman ♦ Will Hare as Pa Peabody ♦ Ivy Bethune as Ma Peabody ♦ Jason Marin as Sherman Peabody ♦ Katherine Britton as Daughter Peabody ♦ Jason Hervey as Milton Baines ♦ Maia Brewton as Sally Baines ♦ Courtney Gains as Mark Dixon ♦ Richard L. Duran as Libyan Terrorist ♦ Jeff O'Haco as Libyan Van Driver ♦ Johnny Green as Scooter Kid #1 ♦ Jamie Abbott as Scooter Kid #2 ♦ Norman Alden as Lou Caruthers ♦ Read Morgan as Hill Valley Cop ♦ Sachi Parker as Bystander #1 ♦ Robert Krantz as Bystander #2 ♦ Gary Riley as Guy #1 ♦ Karen Petrasek as Girl #1 ♦ Buck Flower as Red Thomas ♦ Tommy Thomas as Starlighter ♦ Granville ‘Danny’ Young as Starlighter ♦ David Harold Brown as Starlighter ♦ Lloyd L. Tolbert as Starlighter ♦ Paul Hanson as Pinhead-Guitarist ♦ Lee Brownfield as Pinhead ♦ Robert DeLapp as Pinhead ♦ Charles L. Campbell as 1955 Radio Announcer (voice) (uncredited) ♦ Deborah Harmon as TV Newscaster (uncredited) ♦ Huey Lewis as High School Band Audition Judge (uncredited) ♦ Tom Tangen as Student (uncredited) ♦ Mary Ellen Trainor as TV News Anchor (uncredited)

Directed by: Robert Zemeckis

Written by: Robert Zemeckis

Written by: Bob Gale

Executive producer: Steven Spielberg

Executive producer: Kathleen Kennedy

Executive producer: Frank Marshall

Producer: Neil Canton

Producer: Bob Gale

Original music: Alan Silvestri

Cinematography: Dean Cundey

Editing: Harry Keramidas ♦ Arthur Schmidt

Casting: Jane Feinberg ♦ Mike Fenton ♦ Judy Taylor

Production design: Lawrence G. Paull

Art direction: Todd Hallowell

Set decoration: Hal Gausman

Costume design: Deborah L. Scott

Makeup and hair: Ken Chase ♦ Dorothy Byrne

Unit production manager: Jack Grossberg

Unit production manager: Dennis E. Jones

Post production supervisor: Arthur Repola

Stunts: Walter Scott ♦ Charlie Croughwell ♦ Richard E. Butler ♦ Loren Janes ♦ Max Kleven ♦ Bernie Pock ♦ Spiro Razatos ♦ Robert Schmelzer ♦ John-Clay Scott ♦ Per Welinder ♦ Bob Yerkes ♦ Terry Jackson

Special thanks: Mark Campbell ♦ Ron Hitchcock ♦ Gregg Landaker ♦ Steve Maslow ♦ Tim May ♦ Stephen Semel