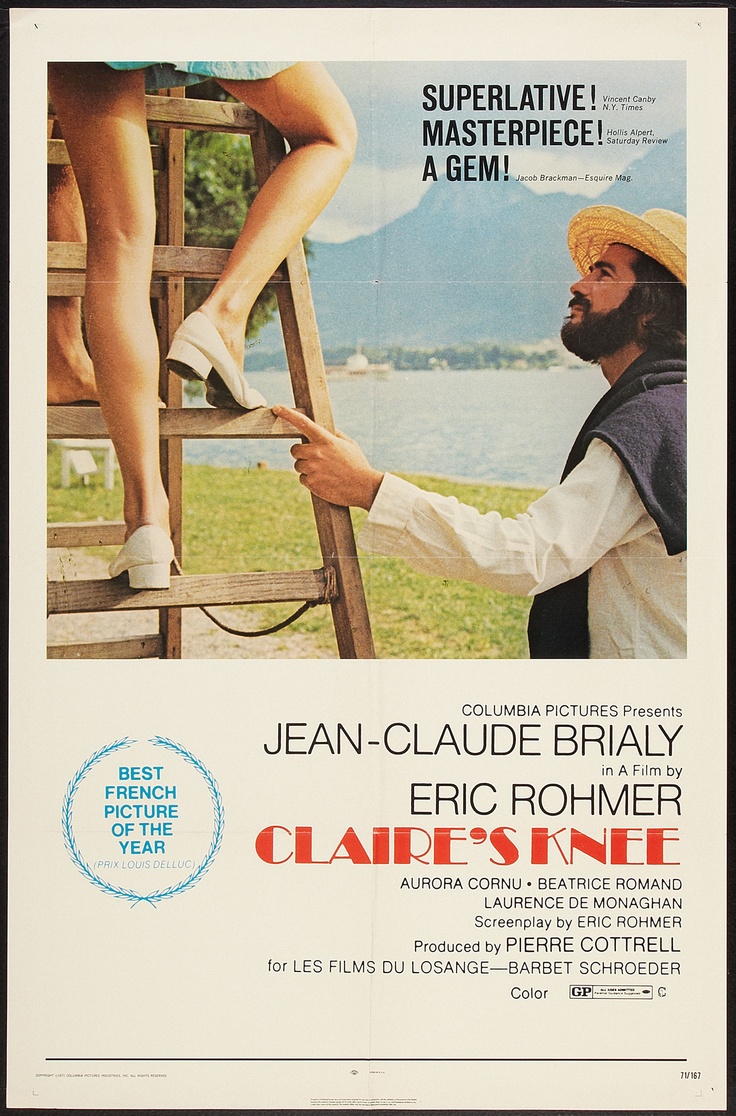

Knee-buckling visuals make

‘Claire’ one for the ages

The critical question in “Claire’s Knee” is whether Claire even cares in the slightest about the man who is contemplating her. She does not. That should negate everything this film purports to be.

It doesn’t.

“Claire’s Knee” is fantasy in search of a catch. Here you have a handsome male diplomat, late 30s, in the beautiful French Alps, still single, albeit engaged, to a woman conveniently in another country. He apparently owns a vacation house here, implying wealth. He’s quickly surrounded by attractive women, including a pair half his age. Not only can he look, he is given carte blanche to court them by a galpal of his own age who is an author and somehow thinks this might make a good story. She even tells him, “I have been interested in a few young boys. ... I never went through with anything.”

The diplomat, Jérôme, complains about being a “guinea pig” for his friend Aurora’s writing inspiration, but when Aurora points out that she will chronicle the dynamic here whether he consciously participates or not, he sees no downside.

“Claire’s Knee” is the 5th of French New Wave director Éric Rohmer’s “Six Moral Tales,” a collection of films he put together in the 1960s. The whole series comes down to availability, the presumption being that a man is always looking, and even the wrong woman at the right time is going to be very tempting. Because Rohmer has draped “Claire’s Knee” in such innocence, it thrives against its flurry of taboos. Never does it feel sleazy. Part of that is the masterful, gorgeous setting. It is undeniably beautifully shot, mountains, lakes and canals that somehow assure us that nothing untoward will happen here, one of those films in which nature will keep the humans in line. Another reason is the friendship Jérôme shares with Aurora, the type rarely portrayed in film. They are constantly shown cuddling with each other. They completely enjoy each other’s companionship, confidence and trust. There is no sexual tension though they might be made for each other. Surely Jérôme’s offscreen fiancee, Lucinde, would admit jealousy of their rapport, but maybe it would be more like admiration. This is a powerful curve ball from Rohmer, who has somehow made a woman’s friendship even more compelling than the sight of a perfect bikini body.

The movie peaks when Jérôme meets Claire for the first time. This is a holy-moly visual that for Jérôme, once it happens, it can’t be undone, but for him, no image of Claire after that can ever be as powerful. He has seen a small photo of Claire but nothing that would prepare him for this moment. Many attractive women have appeared in a movie in a bikini, but few have done it with Claire’s spectacular nonchalance. This meeting is an interesting contrast with Blake Edwards’ “10,” a film a decade later in which Dudley Moore’s vision of Bo Derek on the beach occurs in a daydream, after he has already seen her multiple times. After an emotional breakthrough, both films will redirect their protagonists to Plan A.

Jérôme’s encounter is almost laughably businesslike. Claire in this setting is wielding enormous power but seems to have no interest in using it. She gets up from her lawn chair in some kind of anticipation of Jérôme’s visit. She explains the others are gone and smiles when he notes, matter of factly, she’s all alone. Otherwise, they agree it’s a nice day, and once Claire’s boyfriend Gilles pulls up, Jérôme strides away.

Later, Jérôme will reveal to Aurora what seeing Claire means: “desire,” apparently long dormant for him, renewed.

Claire’s “sister” Laura is a different kind of challenge for Jérôme. Without any prompting, he learns she is in love with him, according to Aurora, who knows, because Laura indicated as much and because women always know these things (a fact confirmed later by Laura’s mother). Jérôme is intrigued by Laura’s pronouncements that seem beyond her years (“Actually I’m quite old for my age. ... My friends are much more childish than I am ...”) and the fact she claims to be “spiritually different” than Jérôme’s fiancee, Lucinde (Laura can determine this from a single photo of Lucinde). Jérôme will insist to Aurora that Laura is a “child” and that “I haven’t the time to notice every little girl in love.” But as long as Laura is the only game in town, and because she has a young sophisticated beauty, Jérôme is willing to give her a listen, to notice her appearance in a swimsuit. Once Claire shows up, Laura’s observations feel like lettuce next to ice cream — one of them is a healthier relationship for the long term; the other would be a lot of fun to try right now. Once Laura notices Jérôme’s fixation with Claire’s knee, she hands him a basket with disdain, her faint spell broken.

Pauline Kael, who liked the film but declared it not great, wrote that Laura is 16, and Claire is “probably about 18.” If they didn’t look like those ages, the film probably wouldn’t fly. Actually, Laurence de Monaghan, a beautiful name (Claire), was likely 15 during filming, and Béatrice Romand (Laura) was likely 17. Yet, Jérôme is right: Somehow, despite being far more articulate, Laura seems like the “child,” while Claire appears beyond childhood, confident with the opposite sex.

Cleverly, Rohmer gives Jérôme an interesting rival — Gilles, the hotshot boyfriend of Claire. Gilles is cocky, arrogant, indulgent, demanding, narcissistic, rock-star handsome, and a scofflaw, all good reasons to dislike him. But he has something Jérôme doesn’t — youth, and like Claire lacks the ability or inclination to obsess over the things Jérôme is wondering about. We can infer that if things go south with Claire, Gilles would hardly skip a beat finding someone else. But Claire’s protestations to Jérôme that Gilles stands up for himself do resonate, and Gilles’ explanation to Claire about a controversial event sounds, by teenage standards, plausible, something they can work out. Sweetly concluded, we can tell they belong together.

Kael wrote that the film “deals in self-deception.” Indeed. While Jérôme claims a massive accomplishment, he more likely realizes that after one night with Claire, he would be bored out of his mind.

Rohmer excels at depicting people talking to someone who is offscreen and, at times, showing them listening to someone speaking offscreen. The showdown between Jérôme and Claire takes place when rain falls for the only time in the film, when Jérôme tries to casually inform Claire that Gilles is “way beneath you.” Claire insists, “Your opinion doesn’t interest me at all,” and it doesn’t seem to, except that she seems mildly intrigued that Jérôme is interested in having this conversation. Jérôme insists, “I was never interested in you or your sister and I’m getting married, so I’m absolutely impartial.” He tells of his observation of Gilles. Does Claire cry because she believes him, or because this irrelevant person is so intent on interfering with her charmed life?

Today’s attempt at this genre features a couple in an ultramodern apartment, working late, considerable baggage. Rohmer wastes zero time with schedules, arguments. Kael wrote that the viewer accepts “the way the situation has been abstracted from normal living.” This is a pure play on the contrast between sexual and emotional attraction. He has put a small collection of unusually attractive people together in a Garden of Eden to compare views on relationships. Whatever Aurora plans to do with her story, we don’t care. Whatever Jérôme does for a living, we don’t really know. What he is doing at night (by day, he is supposedly selling a vacation home, but nobody is coming to look, and he is shown doing no work on it), who knows. The viewer wants him to see the girls, share his observations with Aurora, and hopefully not break any laws.

Rohmer’s biggest decision on what to exclude involves the fiancee. We will never meet Lucinde. This makes it easy for the viewer to bless what Jérôme is contemplating. Should he be marrying this woman? That question, almost incredibly, is irrelevant. He hints they might even be planning an open marriage or at least one in which a 3rd-party experience might be easily forgiven. He assures Aurora that they are good to go. Lucinde’s side of the story would be interesting.

Reviews of the time indicate a much different standard for Aurora’s plot. Roger Ebert wrote that while Jérôme and Laura click, “of course the man does not take advantage of the young girl.” But here is a grown, respected man initiating intimate contact with teen girls/women not even half his age, while he’s engaged. He’s got a female collaborator who thinks that’s great. She assures him Claire will age well. “I think she’ll become a beautiful woman. I mean she’ll fill out in the right places.” She asserts that “very few” pretty young women look great at 30 but that Claire will “resist the onslaught” of time. “It’s not too late,” Aurora actually tells Jérôme. “If she suits you, you’re still single. Marry her!”

(The next and last film in Rohmer’s series, “Chloe in the Afternoon,” will have the title character assuming both the Laura and Aurora role. That film is perceptive but gets bogged down in boredom, characters entertaining infidelity because there’s nothing else to do.)

Vincent Canby called “Claire’s Knee” “a superlative motion picture” and “very close to being a perfect movie of its kind.” But he ignores a big problem, that Rohmer depicts nothing special about Claire’s knee. The close-ups of this body part have an emperor-has-no-clothes element. Whatever about it has somehow caught Jérôme’s fancy doesn’t register with the viewer the way everything else about her does. Unlike in “10” (or, in a really offbeat parallel, “Shallow Hal”), we see Claire the way the rest of the world sees her, not the way in which Jérôme is fantasizing about her.

Whatever Lucinde might think of this is irrelevant. Would she be more concerned about his interest in the girls or in Aurora? Jérôme has attained a level of intimacy with each woman. The victory is apparently his realization that his conquest of Claire must not be sexual. Rather, he has exploited her supposed vulnerability by touching her knee. He’s never done anything “so heroic,” he brags to Aurora, and insists it took “a lot of courage.” (Again, we are in fantasy-land here.)

Aurora validates this outcome, stating there is “nothing perverse” about it.

Jérôme declares, “The girl’s body no longer obsesses me ... It’s as if I’d had her, I’m fulfilled.”

It’s inevitable that marrying Lucinde will not be nearly so exhilarating. For those on Jérôme’s wavelength, this is a meaningful picture. For those who aren’t, it’s 90 minutes of absolutely nothing. By autumn, Claire may hardly remember Jérôme, oblivious that she has apparently improved a marriage in Sweden.

3.5 stars

(December 2017)

“Claire’s Knee” (1970)

Starring Jean-Claude Brialy as Jérôme ♦

Aurora Cornu as Aurora, the novelist ♦

Béatrice Romand as Laura ♦

Laurence de Monaghan as Claire ♦

Michèle Montel as Madame Walter ♦

Gérard Falconetti as Gilles ♦

Fabrice Luchini as Vincent

Directed by: Éric Rohmer

Written by: Éric Rohmer

Producer: Pierre Cottrell

Producer: Barbet Schroeder

Cinematography: Néstor Almendros

Editing: Cécile Decugis

Production supervisor: Alfred de Graff