Robin Williams’ therapy

makes ‘Will Hunting’ good

Therapist movies tend to be well-received. “Ordinary People” won some Oscars; “The Prince of Tides” and “Regarding Henry” were popular and are good movies. Psychology seems to allow for the most positive rehabilitative stories. People with physical problems in movies tend to die (“Pride of the Yankees,” “Brian’s Song”) while those with psychological deficiencies are eminently improvable (“The Snake Pit,” “Rain Man,” etc.).

Psychology stories tend to rely on more unconventional therapy and analysis, the outcome is usually the opposite of what would happen in real life, and we are OK with that, because this is a movie, and it entertains. What happens to Will Hunting is no exception.

“Good Will Hunting” feels like instant therapy. It is about society’s inclination to push people who maybe aren’t ready to be pushed. And it’s for those who believe they are academic underachievers. It does not realize how much it flirts with the “person who doesn’t want to be helped” scenario. That is a powerful theme, used to devastating effect in films such as “Leaving Las Vegas” and “Taxi Driver.” Matt Damon and Ben Affleck are happier than that. Where others see reality, they see hope. And so they won’t quite go there.

Strictly on the facts, one has to wonder if Will truly wants the intervention he is receiving. But the cheeriness and brightness of most of the scenes suggest early on, they’re going to get to Will Hunting, one way or another. The filmmakers were either so self-conscious of this angle — or just wanted to keep everyone hanging for as long as possible — that they didn’t even give Will the opportunity to say “thanks,” merely having Sean cut him off with “You’re welcome.”

The script was famously penned by Damon and Affleck, who readily admit they received guidance during the process. Skeptics questioned whether the two could’ve written such an engaging movie so early in their careers, but in fact the script is flawed and probably has the feel of an amateur. (We’ll get to how it won an Oscar a bit later.)

Is Damon himself a closet genius? He went to the public school Cambridge Rindge & Latin, got into Harvard, studied English for a year or so, then dropped out once Hollywood noticed him. Not a bad reason for quitting Harvard. So it’s doubtful this script reflects personal demons, but perhaps is based on people Damon knows.

Presumably, the protagonist is Will Hunting, a 20-year-old disenfranchised genius. Sometimes, though, it tends to be a movie about his therapist, Sean Maguire. By the end, it’s not fully clear which one needed the other more, or which one has gained the most.

This dual approach has been done exceptionally well (for example, the first two “Godfather” movies comparing Michael Corleone with Vito Corleone), but is tricky. “Prince of Tides” also tried this structure, and the results were dubious, the Barbra Streisand character, Lowenstein, ultimately violating every personal and professional vow on her way to becoming liberated. “Good Will Hunting” has a different problem in that Robin Williams, as the therapist, is too good, appearing with actors not (yet) at his level, and his supplemental performance tends to be more appealing than the story of the protagonist. This is why “Hunting” is not a great movie, though highly watchable.

The premise of the film is flat-out impossible. The idea that one of the world’s top six mathematicians would be doing janitorial work at MIT is inconceivable. Will references Mozart and Beethoven, but these are poor analogies. Musical prodigies have been common throughout history, sometimes emerging around age 3 or 4. But even the very best mathematicians require years of training under other elite mathematicians. The idea that Will, when he’s not getting into playground scraps, can solve almost unthinkable problems at age 20 simply by reading books is ludicrous.

Even so, that absurdity can be overlooked. The erratic portrayal of Will, by Damon, is a bigger problem. According to an early scene, Will has a horrendous, hidden temper. He brutally attacks a kindergarten rival for no reason, other than the fact he saw him on the street (after seeing him at a baseball game and doing nothing). But never again do we see any violence from Will, not even when he and a friend are needlessly provoked at a Harvard bar, where Will is the epitome of gentlemanly conduct. Nor does he become violent with his girlfriend, instructor or various therapists during rough moments. So we have a scene of shocking violence, unsupported by everything else in the film, ginned up to serve as the plot catalyst. To call this an unreal movie is to be kind.

“Sling Blade” is a movie that comes to mind as an effective depiction of a violent person, someone who struggles to control his rage but maybe never really can. Once Will’s aggravated assault is in the books, that option’s done here; he moves on to more genteel problems, like insecurity, lack of focus and fear of rejection.

Will isn’t the only character poorly defined for this movie. Professor Gerald Lambeau, played by Stellan Skarsgård, is a train wreck. The script needs Lambeau for 2 reasons, to serve as a benchmark for Will’s talent and to deliver him to Sean, but is never comfortable with him. He is clumsily portrayed as part enabler, part obstacle. Several times he indicates altruism, wanting to see Will’s talents benefit the world. Other times in his arguments he appears exploitative, seeking to impress his friends at McNeil or whatever other think tanks he wants Will to work at for $80,000 a year. He notably condescends to this admitted superior 20-year-old mathematician by regularly calling him a “boy.” He somewhat exemplifies the type of genius Sean mocks in his lakeside chat with Will, a smart male with no understanding of the value of a woman (Lambeau notoriously asks a female student to a Saturday night drink). Realistically, Lambeau does deserve most of the credit for Will’s makeover. He cared, took a chance, was patient, found Sean. In the end, he is not wanted, dismissed as easily as Will’s construction job. There’s a message here: If you care enough to help, don’t bring an ego.

Lambeau sets up Will with a series of job interviews (a low point for the film, discussed below). What is strange is that a premier academic like Lambeau would want such a prized pupil to go work for a company or the government. He suggests that will provide “freedom” for Will’s academic pursuits. Is Lambeau some kind of simmering capitalist or CIA-phile? One would think most professors would want Will to teach at MIT, CalTech, University of Chicago, maybe join Fermilab, and win a Nobel Prize.

The film struggles mightily to sort out these sentiments, unlike its polar opposite, “Patton,” which is also reviewed on this site. Here Lambeau is Patton, trying to drive Will to the apex of mathematics. He is not particularly appreciated. The therapist is the hero. He battles the invisible enemy that geniuses like Lambeau can’t detect. The therapist’s victory is in guiding Will past his demons to receive some kind of personal satisfaction, although it is presumably a satisfaction that would allow Will to freely pursue the path Lambeau envisions for him without beating people up along the way.

“It’s not your fault” ... this is what we’re left with as the summation of Sean’s assessment, a disappointingly shallow slogan in a film with much higher goals. Maguire’s best observation is undoubtedly “Maybe you’re perfect,” an unexpected body blow to the perceptions we all seem to have, on some level, of the admirable people we meet who somehow make us uncomfortable. Is Sean also coaching himself to believe in life as a widower? The tragic death of Williams in 2014 suggests he might well have drawn on his own therapeutical experience.

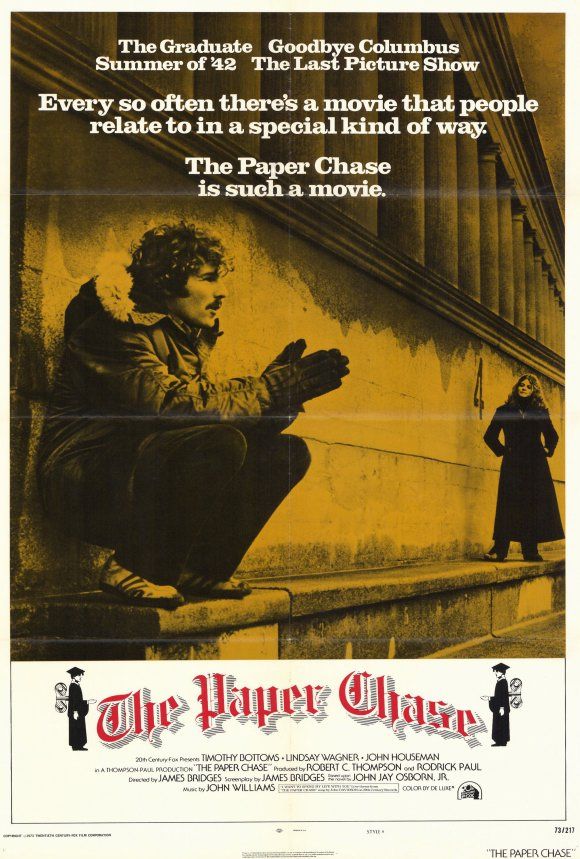

There is nothing noteworthy about the cinematography. Most of it is people sitting in a room, talking. The classroom shots differ from those in most elite academic movies, such as “The Paper Chase,” “Soul Man” or “Mona Lisa Smile.” Those movies succeed in putting hotshot young brains on the spot under intimidating professors. Lambeau’s MIT classrooms are informal, unthreatening.

The film is overly reliant on dialogue. There are some hugs, some tears, some shouting, but to delve deep into the souls of Will and Sean, you’ve got to listen to speech after speech.

A few scenes, though, do elevate the film. The first is when Maguire suddenly grabs Will, whose face, just in front of the camera, had carried a look of disdain as he dissected one of Maguire’s paintings. This scene’s importance is monumental. In real life, we know that Will, a very troubled and violent person who has met dozens of therapists in his young life and treated all with disdain, would likely tear Maguire to shreds. There would be another arrest and Lambeau and Skylar would give up. Furthermore, if one gives this scene significant thought — make that too much thought — one might reach the conclusion that Sean reacted in a very amateurish way that calls into question his credentials, that he should not be bothered by Will’s comments but relieved, because he suddenly understands how brilliant Will is and yet how wrong his description of the painting is, a realization that could’ve prevented a sleepless night.

But the scene nevertheless works, because Williams is a guy you don’t want to mess with on any level, and to have a violent genius acknowledge this by backing down is an extraordinary depiction of Sean’s chops.

Later, Sean takes Will out of the office to a lake, the openness suggesting Will is going to be treated as a human being from now on, not a lab subject; notice that, as in most therapy films, Will’s chutzpah and defiance and invented phoniness disappear in a natural environment.

Finally there is a tour de force by Minnie Driver in the devastating argument between Will and Skylar. Driver can bring viewers to tears with a staggering instant transformation from offense to defense. She makes a long-sought breakthrough, immediately realizes its consequences, and sensing the make-or-break nature of this moment, fights valiantly, unsuccessfully, without self-pity.

The movie also excels in how it depicts Will’s genius. Lambeau notes that only a handful of people in the world could tell the difference between him and Will. Showing that difference is a problem. Director Gus Van Sant uses a memorable bar scene, where Will dresses down a boorish Harvard student with factual recall that is completely impossible yet highly entertaining, and a more poignant scene where a jaded Will burns a proof he’s done, only to have Lambeau stumble to extinguish the fire and save the pieces.

Most fans of the movie like the Harvard bar scene in particular. (See the transcript here.) It’s reminiscent of the theme in “Breaking Away,” of the low-class “towners,” led by one freakish talent, conquering the snobby college guys. But even this scene has problems. Will’s points are overly long and clunky. In an example of unintentional irony, Will decries the Harvard guy’s lack of originality, when Will himself seems to do little more than memorize books, a point we’ll soon learn.

Unfortunately the episodic material cuts both ways. There is the comical scene where Will enlists his buddy Chuckie, played by Ben Affleck, to sit in for him at a very serious job interview. This scene lasts too long and is such a farce it doesn’t belong in a movie with these kinds of aspirations.

Perhaps an equally bad moment is in another job interview, this one actually attended by Will, where shadowy government insiders ask him why he wouldn’t want to work for the National Security Agency. This morphs into a soliloquy in Sean’s office. This scene further dilutes Will from a movie character into a Damon manifesto. It is not a neat curveball, but a wild pitch, suggesting a much different excuse than what we’ve been led to believe all along about why Will is an underachiever, that he is apparently concerned about the government exploiting his ability. And we thought all along he just had orphan abuse issues. Sean should tell him — but doesn’t — that while there are many good reasons for underachieving as a student or scientist, wariness of the government is not one of them. Another example of our Oscar-winning screenwriters throwing in the kitchen sink, including their own views about government institutions.

One of the most interesting lines of “Hunting” comes not at the end, but beyond the end, when the credits are virtually complete. The text says something probably few noticed: “In memory of Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs.”

Williams is the gem of the movie. He carries it, because of the way he acts with his eyes. You see the sense of humor, but also the fatigue, the pain of a talented, directionless man who has lost the love of his life and seems to wonder if there’s anything else. How Will reinvigorates him isn’t totally clear. Sean is lonely, perhaps somehow friendless. There is an implicit message here, as in every psychology movie, that there is no greater therapy than talking. It’s far superior to even an MRI at pinpointing trouble, and you can’t possibly overdose on it.

Skylar is likely the first woman Will ever dated who actually graduated from high school. Driver is one of the few in this cast who can match the standards set by Williams. Her affection for Will is believable, as is her skepticism. She is highly convincing as a Harvard brain. But would she really be so eager to move to California with a man currently on probation for nearly beating someone to death merely because he saw him on a street 15 years after a childhood scrape?

There is limited chemistry between Will and Skylar. She picks him, because he impressed her at a bar, but he was unimpressed by her and it’s unclear what he sees in her. We are led to believe he wants her but is afraid to come to grips with that. It’s a very difficult nuance; he must be in awe of her and still feel inferior to her at once, and Damon never makes the sale for why Will wants Skylar. It cannot be for her brain; their conversations are Chuckie-caliber. Anyone willing to disregard Willful Suspension of Disbelief for just a moment will quickly realize Will and Skylar don’t belong together, no matter how cured Will gets.

It may forever be debated whose project this was. Van Sant has had a few hits but this doesn’t seem like his vision, whatever that may be. Most likely, Damon was viewed as a rising star, persuaded a few Hollywood bigwigs to bankroll a fairly low-budget production, talked Williams into taking a role, then whoever put up the most money probably dictated a few changes.

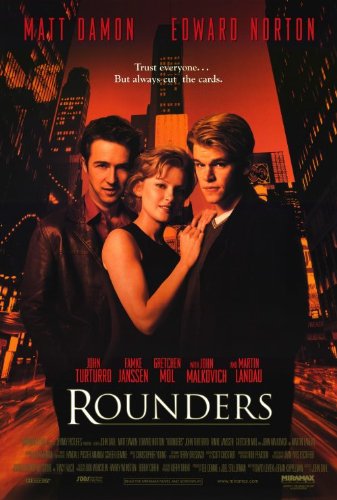

This was not the only time Damon was out-acted: As the protagonist, he was upstaged in “Rounders” (a film also reviewed on this site) by Edward Norton, like Williams an extraordinarily gifted actor who is much more than an attractive face. Damon, a great student of acting, is a prized mainstream commodity, in the bankable sweet spot of being very well-liked by women as well as acceptable to male viewers (unlike, say, Jude Law). His persona hasn’t yet proved it can carry a 4-star movie, but his is a reassuring face that succeeds in special-effects projects like the “Bourne” series or as an ensemble character in films such as “Syriana,” “Saving Private Ryan” or the “Ocean’s 11” series. Many actors have liberal viewpoints. Damon is highly educated, articulate and pointed, not to mention deep — few people his age have even heard of Ginsberg and Burroughs. It’s possible that the original “Hunting” script he and Affleck wrote much more reflected how the establishment ruins things and people like Will. But Damon is well aware of his mainstream box office potential and generally keeps his semi-polarizing political viewpoints under the radar, unlike Sean Penn. One has to assume the dedication to Ginsberg and Burroughs did not come from Skarsgård.

Williams’ performance in “Hunting” clearly blew the Oscar voters away, and how could they not want to reward the improbable young screenwriting duo who put it all together? Incredibly, “Hunting” was nominated for a host of Oscars, including best picture, best actor for Damon, best supporting actress for Driver, best director for Van Sant. That was the year of “Titanic” as well as a host of other excellent movies such as “L.A. Confidential,” “Boogie Nights” and “As Good as it Gets.”

The feeling here is that “Hunting” will gradually be forgotten. That is not to dismiss the appeal of Damon and Affleck, which is considerable, but the film’s fundamentals, which are suspect. The writers’ great success here was to persuade Robin Williams to play a therapist. It’s been a great story since “Hunting” debuted, these two pals from Boston, acting together, writing screenplays together, including their circle of friends such as Affleck’s brother Casey and Driver (for a time), then J. Lo, and this is what the public seems to identify with, much more than the characters they play. It’s a real-life success story that to this day is usually good for a couple box office hits a year.

The best question posed in “Hunting” is “Will, what do you want?” A decade later, we still don’t know.

3 stars

(August 2008)

(Updated December 2015)

“Good Will Hunting” (1997)

Staring Robin Williams as Sean Maguire ♦ Matt Damon as Will Hunting ♦ Ben Affleck as Chuckie Sullivan ♦ Stellan Skarsgård as Professor Gerald Lambeau ♦ Minnie Driver as Skylar ♦ Casey Affleck as Morgan O’Mally ♦ Cole Hauser as Billy McBride ♦ John Mighton as Tom ♦ Rachel Majorowski as Krystyn ♦ Colleen McCauley as Cathy ♦ Alison Folland as MIT Student 1 ♦ Derrick Bridgeman as MIT Student 2 ♦ Vik Sahay as MIT Student 3 ♦ Shannon Egleson as Girl on Street ♦ Rob Lyons as Carmine Scarpaglia ♦ Steven Kozlowski as Carmine Friend 1 ♦ Jennifer Deathe as Lydia ♦ Scott William Winters as Clark ♦ Philip Williams as Head Custodian ♦ Patrick O’Donnell as Assistant Custodian ♦ Kevin Rushton as Courtroom Guard ♦ Jimmy Flynn as Judge George Malone ♦ Joe Cannon as Prosecutor ♦ Ann Matacunas as Court Officer ♦ George Plimpton as Henry Lipkin ♦ Francesco Clemente as Rich ♦ Jessica B. Morton as Maurine ♦ Barna Moricz as Vinny ♦ Libby Geller as Toy Store Cashier ♦ Chas Lawther as MIT Professor ♦ Frank Nakashima as Executive 1 ♦ Christopher Britton as Executive 2 ♦ David Eisner as Executive 3 ♦ Bruce Hunter as NSA Agent 1 ♦ Robert Talvano as NSA Agent 2 ♦ James Allodi as Security Guard ♦ Kent Damon as Chess Game Player ♦ Harmony Korine as Jerve

Directed by: Gus Van Sant

Written by: Matt Damon

Written by: Ben Affleck

Producer: Lawrence Bender

Co-producer: Chris Moore

Executive producer: Su Armstrong

Executive producer: Jonathan Gordon

Executive producer: Bob Weinstein

Executive producer: Harvey Weinstein

Co-executive producer: Scott Mosier

Co-executive producer: Kevin Smith

Original music: Danny Elfman

Cinematography: Jean-Yves Escoffier

Editing: Pietro Scalia

Casting: Kerry Barden, Billy Hopkins, Suzanne Smith

Production design: Missy Stewart

Art direction: James McAteer

Set decoration: Jaro Dick

Costume design: Beatrix Aruna Pasztor

Makeup and hair: James D. Brown, Jean Carney, Elizabeth Cecchini, Leslie Ann Sebert

Stunts: Jery Hewitt, Brian Ricci

In memory of: William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg