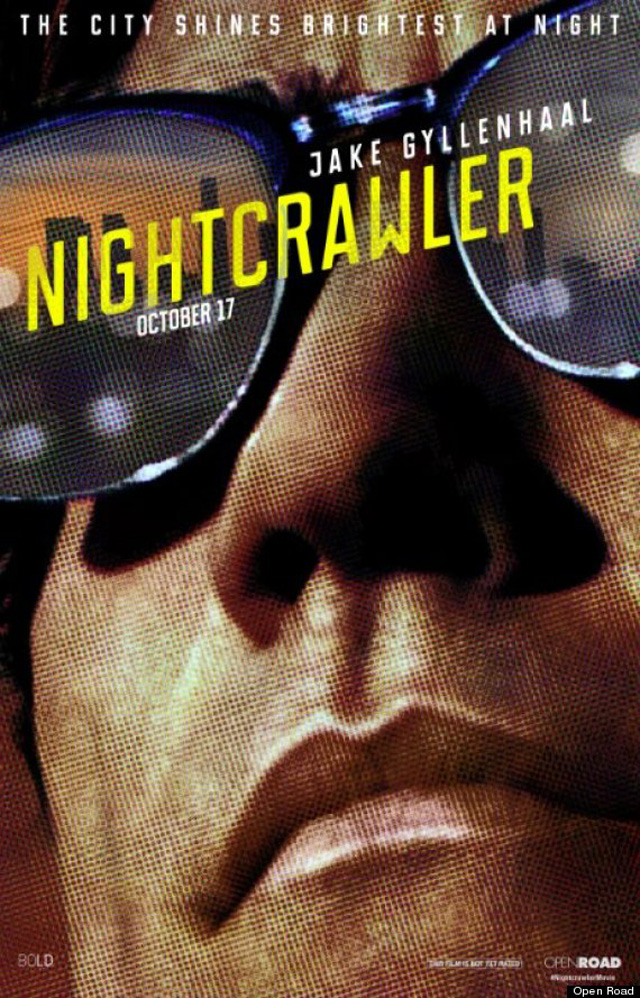

‘Nightcrawler’ shows us

where there’s tragedy,

there’s opportunity

All of the parties in “Nightcrawler” agree that accident and crime footage drive TV ratings.

You have to take their word for it, because depicting this implication is a challenge.

If you focus on the subtleties of “Nightcrawler,” you will probably reach the opposite conclusion. Surely if this type of footage was critical to ratings, Rene Russo’s station would employ a professional night crew to unearth it. Or at a minimum, actively court potential free-lancers. That kind of material is unreliable in terms of its frequency and in terms of what rival stations might pay to procure it for themselves. Relying on characters such as Lou Bloom to walk in the door at 2 a.m. and find their way to the video room seems not the surest business model.

Regardless, we get it. “Nightcrawler,” which falls under the category of Western, is remarkable for its vivid illustration of an important concept not easily visualized: supply and demand. We’d prefer to think otherwise if thinking about it at all, but many of our guilty pleasures are provided by less-than-ideal next-door neighbors.

Numerous films have skewered the faults of television. “Nightcrawler” is the counterpart of “The China Syndrome,” which finds corporate interests overruling public safety. Each movie presents a battle over the airing of footage. It should come as little surprise that of the two films, the video obtained under the more agreeable of standards is the one that is shelved. (This is Hollywood, after all.)

“Nightcrawler” unabashedly is over the top. As it should be. Rookie director Dan Gilroy correctly marries his plot with Lou’s product. When was the last time on your evening news you saw video of still-warm murdered bodies? From his opening scrape, it’s hard to believe Lou emerges with an expensive watch and no apparent ramifications. He was in his car, on private property surely stocked with surveillance cameras. There is dystopian implication here, the suggestion that normal society isn’t interested in policing the likes of Lou.

Perhaps even more over the top is the refreshing notion that actual old-fashioned television, not the Internet, is the gold standard of today’s media.

Blood, guts and tragedy are highly in demand in “Nightcrawler.” Bad neighborhoods clearly are not. The characters are unanimous in wanting nothing to do with them. They are dangerous, hopeless and uninteresting. The nighttime scenes of cinematographer Robert Elswit are unsparing but not altogether grim. Rather, they depict ... potential.

In the race to the bottom, television proves a most attractive way station. The scrapyard buyer of Lou’s copper is certain where it comes from. He takes it anyway, but he refuses to consider Lou for a job. Lou has a much better chance with Nina Romina, who accepts Lou as well as his product. In a strange and beautiful character assortment, savvy and hustling entrepreneurs are 100 percent comfortable with the grim reality of the world they live in, allowing them to thrive in it.

Gilroy told “Last Call with Carson Daly” in October 2014 that “Lou’s strength is that he’s unencumbered by any sense of morality or wrongdoing.”

What would be an analysis of Lou’s boundaries? Murder seems to be part of his repertoire, but a crucial distinction must be noted: Lou is not pulling any triggers. He finds himself the choreographer of society’s mayhem, pushing buttons when necessary.

What he does throughout his 911 collar is reprehensible. Cleverly, whether any of it amounts to an actual crime is doubtful. He has withheld evidence, yes, but only for a short period of time. Falling into the gray area of credentialed journalist, he likely has some protection beyond that of an ordinary citizen. Assuming the culprits did not harm someone else after the home invasion, he is likely off the hook for that transgression.

He is certainly to blame for one person’s death, but the killer is also deceased. Even if authorities had video of this offense, it would be difficult to prove Lou was expecting the killer to start firing. But there are no witnesses and obviously no case would ever stick here, let alone come to the attention of someone to bring it in the first place.

One rare lapse occurs as Lou summons police to an Asian restaurant. The film is trying to show that under the guise of assisting society, Lou is secretly manipulating officers into a bloodbath. In fact the police, given such ample information about the suspects, would have been prepared with more than their chop suey orders and would only have themselves to blame for their incompetent approach. The film deserves a more creative entanglement. From that scene and the first scene, there’s a mild hint here that authorities are so incompetent, society is better served not even calling them.

One crime would be overlooking Jake Gyllenhaal for Oscar consideration. In such an intriguing setting, splendid actors capable of “disappearing into a character” can be underestimated. For Lou, Gyllenhaal famously lost a lot of weight, then updated the look of Lt. Col. Frank Slade from “Scent of a Woman,” recognizing it’s downright creepy for such a young man, then threw in some quirks of Norman Bates and Raymond Babbitt. We get a character who should be detestable, yet because of his earnestness, politeness and statistical recall, is somehow marginally likable ... or, like his material, at least watchable.

A crucial moment occurs when Lou happens upon his first accident scene. (There is a different reaction here to such a spectacle than in Oliver Stone’s “The Doors.”) Every one of us has driven by an accident. The plot hinges on this particular tragedy inspiring Lou, who evidently has no audio/visual background, to take up spot-news video full bore. It seems a stretch that a person in his situation would sell/trade possessions for a cheap camera to embark on this uncertain line of work. But we know he needs a job, and Bill Paxton’s Joe Loder has convinced Lou that it’s profitable. Thanks to Gyllenhaal’s uncanny focus, we’re sold.

Antiheroes come and go. Lou is certainly not among the tragic, handsome scoundrels of “Bonnie & Clyde” or “Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid” or “Wall Street.” He has more in common with the nonchalant protagonist of “The Social Network” (though it should be noted that person is not associated with deaths, just financial stiff-arming). When one sets aside Lou’s bankrupt morality, an interesting success story emerges. Gyllenhaal’s Lou makes his own breaks in life and doesn’t wait around for anyone to pass judgment.

Rene Russo, underrated as models are going to be in this business, is as devastatingly effective as Lois Chiles in “Broadcast News,” except much more is required of Russo.

We all have to make a living. “Nightcrawler” never faults Nina Romina or her overnight team of execs/lawyers for their broadcast decisions. They are not instigators of TV mayhem but providers of it. They stand up for the First Amendment. They blur faces.

Based strictly on what is said, the film would have us believe that ratings — an unshowable concept — drive Nina’s questionable decisions. There’s perhaps a stronger motivation behind what she, her team and Lou are doing: They like it. It’s exciting work. High drama. Fresh murder scenes. Accident victims struggling for their lives. On-the-spot decisions. And it’s not just a thrill. Whatever it’s truly worth, it pays well.

Initially it stretches belief that Nina would accept a dinner request from Lou. This scene is unpredictable, delicious. Sanity appears to prevail at the table as she rigidly explains to him and viewers why they will not be a couple.

Lou, however, is ahead of her. He knows what she wants and that he can produce it. She seems to have drawn a firm line. Yet Lou quietly has the better argument. He’s helping her. He wants her. Badly. Realistically, many news executives in Nina’s position are jaded and looking to the next stop. Russo conveys the sudden excitement of her profession. She makes Lou’s arrival equivalent to the future Rookie of the Year being called up to the last-place parent club.

In a remarkably deft touch, Gilroy leaves the Lou-Nina relationship in the background. She’s a former TV anchor; we would assume she has plenty of male suitors. But maybe not. She is middle age; she works overnight shifts. When the nature of her partnership with Lou is made clear during a tirade by him, it is unexpected, but understandable. This is a rare example of dialogue being more powerful than a visual.

Realistically, the dalliance would likely soften Lou up. Instead he is only more intense. What is his end game? He seems en route to madness. But by the end he is as diligent as ever. Presumably at some point there will be bigger fish than Nina. Or, as in “Broadcast News,” the station will undergo the inevitable housecleaning, and she and the staff will cease to matter.

Gyllenhaal, Gilroy and Russo have put together a minor treasure. “Nightcrawler” will not break any records. It will cost us some innocence. Who knew how far we can go without that anchor called “conscience.”

3.5 stars

(December 2014)

“Nightcrawler” (2014)

Starring Jake Gyllenhaal as

Louis Bloom ♦

Michael Papajohn as

Security Guard ♦

Marco Rodríguez as

Scrapyard Owner ♦

Bill Paxton as

Joe Loder ♦

James Huang as

Marcus Mayhem Video ♦

Kent Shocknek as

Kent Shocknek ♦

Pat Harvey as

Pat Harvey ♦

Sharon Tay as

Sharon Tay ♦

Rick Garcia as

Rick Garcia ♦

Leah Fredkin as

Female Anchor ♦

Bill Seward as

Bill Seward ♦

Rick Chambers as

KWLA Anchor Ben Waterman ♦

Holly Hannula as

KWLA Anchor Lisa Mays ♦

Jonny Coyne as

Pawn Shop Owner ♦

Nick Chacon as

Cop #1 ♦

Kevin Dunigan as

Cop #2 ♦

Eric Lange as

Ace Video Cameraman ♦

Alex Ortiz Jr. as

Cop #3 ♦

Carolyn Gilroy as

Jenny ♦

Kevin Rahm as

Frank Kruse ♦

Ann Cusack as

Linda ♦

Rene Russo as

Nina Romina ♦

Kiff VandenHeuvel as

Editor ♦

Christina de Leon as

Barred Door Woman ♦

Juan Fernandez as

Reporter Ron De La Cruz ♦

Riz Ahmed as

Rick ♦

Dig Wayne as

Neighbor ♦

Myra Turley as

Female Neighbor ♦

Merritt Bailey as

Freelancer ♦

Lisa Remillard as

Reporter Deena Rain ♦

Jamie McShane as

Freaked Motorist ♦

Manuel Lujan as

Technical Director ♦

Michael Hyatt as

Detective Fronteiri ♦

Christopher McShane as

Reporter Joel Beatty ♦

Price Carson as

Detective Lieberman

Directed by: Dan Gilroy

Written by: Dan Gilroy

Producer: Jennifer Fox

Producer: Tony Gilroy

Producer: Jake Gyllenhaal

Producer: David Lancaster

Producer: Michael Litvak

Co-producer: Stephanie Wilcox

Associate producer: Juliana Guedes

Associate producer: Garrick Dion

Executive producer: Gary Michael Walters

Executive producer: Betsy Danbury

Music: James Newton Howard

Cinematography: Robert Elswit

Editing: John Gilroy

Casting: Mindy Marin

Production design: Kevin Kavanaugh

Art direction: Naaman Marshall

Set decoration: Meg Everist

Costume design: Amy Westcott

Makeup and hair: Donald Mowat, Candace Neal, Joy Zapata, Pavy Olivarez

Stunts: Mike Smith, Jimmy N. Roberts, Matt Berberi, Steve Schriver, Laura Albert, Chad Guerrero, Joe Ordaz, Craig Baxley Jr., Mickey Cassidy, Logan Holladay, Samuel Hubinette, Oliver Keller, Robert Nagle, Charlie Picerni, Mark Riccardi, James A. Smith, Monique McKellop, Tim Sabatino, Brett Smrz, Freddy Bouciegues, Kiralee Hayashi, Terry Jackson, Eric Matuschek, Mehdi Merali, Simon Rhee, Scott Rosen, Monty L. Simons