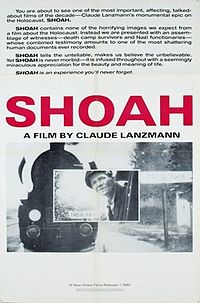

Claude Lanzmann’s ‘Shoah’

not a revelation, but reminder

Villager comments are the haunting relevance of “Shoah,” a film of 40 years ago about something roughly 40 years before that. It’s regarded as a masterwork of testament. Perhaps its greatest champion, the late critic Gene Siskel, called it “the greatest use of film I’ve ever seen in the sense of the good that it does.” Richard Brody dubbed it “one of the summits of cinematic history.”

But is it a “movie”? Not necessarily. “Shoah” is “60 Minutes” times 10. It’s a statement, and a very powerful one. Actually too powerful to rein in Lanzmann, whose unpolished, renegade directorial approach drains the material of focus and visually settles for repetition.

This page is by no means reviewing the Holocaust, only a film. Criticism of “Shoah” is not to be offered lightly. These are not professional actors working on their next gig. These are severely traumatized human beings courageously volunteering their stories. But as a film, “Shoah” can and should be evaluated by typical cinematic standards. It is extremely impressive as a compilation, much less so as a work of art.

Over 9 hours, “Shoah” somehow lacks backstory. The presumption is that viewers know what happened. “Shoah” presents what they may not know: details of large groups of people in their final moments. And details of what onlookers still think about it. Some of these details are very important; others less so. Too many of the interviews are unwieldy, sometimes never reaching an anticipated conclusion.

There is no need for “Shoah” or any film about such a massive event to cover all the bases. It’s a big mistake to try. The problem for Lanzmann is that his hyperfocused film is anchored to virtually nothing. You can start watching at the first minute or 8th hour, it’s the same impact.

Siskel said that Lanzmann spurned “vintage death camp footage” in favor of the spoken accounts, and “we don’t need anything more than their words to know the shame of it all.” But we do need more than words to fortify a 9½-hour film. Pictures of this catastrophe say more than the words, and Lanzmann offers virtually no historical pictures. You can find them on Wikipedia or Holocaust memorial sites. In “Shoah,” the deceased are never shown. Lanzmann’s preferred imagery is the 1980s train running near the camp sites. To fill 9½ hours, he relies on the same clips of footage perhaps dozens of times, mostly of trains but sometimes from horse-drawn carriages around the Polish communities. Initially haunting, they become repetitious. His message from this footage: Do you dare let this go away?

Lanzmann surely must’ve been informed by Marcel Ophüls’ stellar 1969 work “The Sorrow and the Pity,” which employs the same interview approach as Lanzmann but augments the testimony with powerful historic footage. That film addresses the strange relationship between the Nazis and Vichy France, in some ways, incredibly, a mutual admiration society. Those who see both “The Sorrow and the Pity” and “Shoah” will know by the second one what’s coming — the outrage isn’t going to be nearly as universal as one might think.

Words are limited. Very limited, actually. They fail to convey the magnitude of this story, yet “Shoah” is mostly words. That is a struggle also for a review such as this one, in particular assigning a single word to this event. “Holocaust” is the predominant term, but that word appeared regularly for different reasons in the New York Times going all the way back to the mid-1800s, per an online search. The film is titled “Shoah” after the Hebrew term for annihilation. “Catastrophe,” “horror,” “apocalypse” are all fitting, but none particularly unique to this event; no grand description will be attempted here.

Relying on words, translation in a 9½-hour film becomes an issue for English-speaking audiences. Lanzmann primarily speaks French or German to his interpreters, who relay his questions in Polish or other languages. Then come the responses and the translated responses to be narrowed down for the subtitles. Many times, it feels like English-speaking viewers are missing something in the dialogue.

What drives the film is Lanzmann’s insistence this must be told. He wasn’t at the camps, but he insists the survivors talk, and they can’t resist him. (Whether any survivors declined to talk is not shown in the film.) What they say is undeniably authentic. A couple of the Jewish survivors smile while talking. Lanzmann asks survivor Mordechaï Podchlebnik about this in the early minutes of the film; he says it’s best for the living to smile.

It is basically universally agreed in academic circles that the more information about history, the better. “Shoah” walks a very thin line between adding knowledge and trumpeting a disaster. Film productions are not really about how things were, but how things are. “Shoah” was begun in the mid-1970s, shortly after Israel had fought a couple of existential wars and long after the Nuremberg trials and the Eichmann trial and the Treblinka trials, and released in 1985. Attitudes change over time. Imagine attempting this film around 1950, when camp survivors relocating to the state of Israel initially were “looked down upon for the passivity they had supposedly shown as they were marched into the gas chambers.” Even starting in the mid-’70s, Lanzmann in a 2013 Criterion Collection interview says more money for the film came from France than Israel.

The appreciation of the accounts of “Shoah” can be tied to that of the entire World War II era, the fascination of which has only grown parabolically since “Shoah” was begun. The term “Greatest Generation,” the title of a Tom Brokaw book typically applied now to Americans who fought the Germans and Japanese in World War II, does not appear in The New York Times until late 1998 and is not used in reference to those, for example, who served in Vietnam. Steven Spielberg did “Schindler’s List” in the 1990s, not the 1970s.

“Shoah” raises questions about lies and the response of the doomed. Victims were given a diet of virtually nothing but falsehoods. According to some accounts in “Shoah,” they nevertheless sometimes refused to believe the truth. Or did they? It is almost astounding to think of people in groups of hundreds or thousands getting aboard a train, then disembarking and walking into a room to be gassed, followed by another group, exactly as the monsters insist. But what is the alternative other than to hope it doesn’t happen.

It seems human beings facing execution probably very rarely attack the executioners. Imagine someone charging a firing squad or attempting an attack on the gallows. Perhaps there’s a sense that if people are about to kill you, disrupting their process will make it even worse. “Shoah” indicates that family members and friends faced the end together, something the Nazis couldn’t fully prevent.

“Shoah” curiously keeps the Nazis mostly offstage. The film wavers between implying they have been dealt with and implying that not all of them have been. Either way, 40 years later, is the time to remember ... and test the imprint left by this catastrophe.

Despite its ramifications for humanity and the whole world, “Shoah” is about a distinctly European event. These are people of Middle Eastern origin spread throughout the continent, terrorized largely by one particular country seizing most of the land, the worst of all worlds. For whatever disturbing reasons, the Nazis had a higher regard for people from the western part of the continent than the east. But xenophobia was hardly limited to Nazi Germany, and there are hints in “Shoah” that other European ethnicities were not particularly sorry to see Jews quarantined. “Shoah” shatters the notion of people not knowing what is happening. Decades before the internet, it’s fairly clear, people figured it out. People saw Jews being shipped, repeatedly, to death camps. Some even informed the Jews of this outcome by making slashing signs while trains passed, according to Lanzmann’s footage. Whether the observers could or would grasp the total numbers of what they were seeing — or whether such knowledge would have affected their reaction — is a fair question.

While the Holocaust is typically associated with Germany, “Shoah” is more interested in Poland. That’s where the Nazis put the death camps, and that’s where most of the Jews were. It’s not in the film, but before the Nazis emerged, Polish Jews were the world’s largest Jewish community, numbering 3.3 million. According to Wikipedia’s page on that subject, “On the eve of World War II, many typical Polish Christians believed that there were far too many Jews in the country and the Polish government became increasingly concerned with the ‘Jewish Question.’ Some politicians were in favor of mass Jewish emigration from Poland.”

That goes a long way toward explaining Poles’ comments about the Jews in “Shoah.” When the film was released in France, Poland’s government protested, complaining about the film’s inclusion of stereotypical remarks from “contemporary rural churchgoers.” Siskel singled out one of these scenes, stating a Jewish survivor of Chelmno, Simon Srebnik, is being ignored by the Poles who even in this film did “not acknowledge” his presence as they ignored the Jews decades earlier. That is perhaps an exaggeration, as Srebnik is shown being warmly greeted before Lanzmann and his interpreter begin peppering the crowd with questions, during which Srebnik in fact becomes an onlooker. Does Lanzmann want the Poles to sound insensitive? He clearly finds that interesting, which is artistic savvy.

What’s not included are everyman accounts from a host of other countries who have opinions on this subject too and why it happened even if they never saw a train passing by. Some would renew one’s faith in the world; others probably ...

It is noted in “Shoah” that Poles were massive victims of the Nazis as well. That is an important subject, but that is not this particular film. Siskel said millions died “because a lot of people wanted them dead.” All of the parties of the film seem to agree on one thing, that for these observers of the doomed, there was no stopping what happened, not until the Nazis were defeated. One person interviewed, Jan Karski, an official of Poland’s government in exile recognized for attempting to warn the world before it was all over, tells of being compelled to visit the Jewish ghettoes and reporting to Allied leaders what he saw, with virtually no impact.

The accounts in “Shoah” are undeniably authentic. Notice all the gray hair. But Lanzmann understood the need to strengthen the visuals. It would seem as though Lanzmann just dropped by a barbershop to ask a barber, in the process of a haircut, to describe working the gas chamber in Treblinka. Roger Ebert wrote that the barber, Bomba, “has a customer in his chair.” But in his 2013 Criterion interview, Lanzmann admits the setting for Bomba’s commentary was put together by the film crew, with extras getting haircuts.

Also in that Criterion interview, Lanzmann explains smuggling a camera into a room for the conversation with the convicted Nazi Franz Suchomel, who had agreed to audio only. The camerawork’s fine, but the visuals add little. Suchomel is hard to discern in the grainy black and white footage, and much of these scenes are spent depicting Lanzmann’s camera crew in a van.

Impressively, Lanzmann asks his subjects for specifics rather than offering poor interview questions such as “how did it feel ...?” Yet he belabors many of the details, including his obsession with ramp sizes and train schedules. The interview with Karski is most unsatisfying, with a very long scene setter as Karski tries to keep his composure before revealing only a small amount of compelling details.

Outside of the area of the death camps, Lanzmann curiously portrays those he interviews in splendid settings. We see survivors speaking along beautiful rivers in Europe, we see shots of Manhattan and New Hampshire. Does it matter now where the survivors and experts are speaking from, or is Lanzmann stressing the amount of traveling required for this project?

The snippets of modern big-city imagery, especially that in Germany and Warsaw, recall the ending of the 1978 film “Coming Home,” in which Jane Fonda exits the “Out” door of a grocery; we’re done with Vietnam, on to the next problem. “Shoah” subtly indicates that, despite the catastrophe that occurred on this soil, life goes on. This is effective; a similar realization is accomplished by filming the streets of Dallas around the Texas School Book Depository and noticing people not thinking in that particular moment about Nov. 22, 1963.

Only a couple “Shoah” scenes can be considered extraordinary. One is the scene highlighted by Siskel, when Srebnik returns to Poland and stands surrounded by Poles outside a church. The Poles are eager to answer Lanzmann’s questions and offer remarkably candid answers, some indeed cringeworthy. He interviews those who saw Jews detained in a church, packed onto trucks and trains and gas vans, and those who lived in or near Jewish neighborhoods. These comments are more revealing than those made about the gas chambers. One Pole says the Poles and Jews “hated each other.” A woman insists that Polish men found Jewish women attractive because Jewish women looked beautiful because they didn’t work and could spend all day on their appearance.

Probably the most dramatic moment is late in the film when Filip Müller, a Jewish camp guard, tells of Czech Jews who became aware they were entering a gas chamber and broke out in song, the Czech national anthem, evoking thoughts of the spontaneous anthem in “Casablanca.” Müller says he was moved by their plight to enter the chamber with them, but they told him to leave and someday tell his story.

Some stories are started and not adequately ended. For several minutes, Lanzmann confronts an apparent German guard who now serves alcohol at a restaurant. The man doesn’t want to talk. After a while, Lanzmann moves on, end of story. How did Rudolf Vrba escape? Müller expresses astonishment at discovering a sheet of paper with “SB” on it, the significance unclear. Why were some Czech arrivals at Auschwitz given decent (relative to everything else) accommodation for months before being gassed? Why are Ukrainians assisting the Nazis? All part of the backstory Lanzmann shuns, all findable in the history books on the Internet.

Lanzmann was born in Paris in 1925, a grandson of Russian Jews, protected by arrangements made by his father during World War II. In a 2012 interview, he insisted, “Shoah is not a documentary. The word makes me want to take a pistol and shoot.” Yet that is the film’s description on its Internet Movie Database and Wikipedia pages.

In the 2008 film “The Reader,” a female German camp guard chooses not to fight her guilt, even on technical grounds. (Like a character in “Manchester by the Sea,” she considers society’s judgment irrelevant to her own.) Lanzmann has introduced the 2nd derivative, the co-victim who saw someone else get it worse and doesn’t always sound too broken up about it. That is powerful filmmaking, whatever the context.

The unresolved question of “Shoah” is whether this was a finite event or endless struggle. The Nazis are no longer to be feared (the world’s most hated entity, they are to this day the villains in a handful of films every year), but what about lingering attitudes. Pauline Kael apparently was not impressed by the film and wrote, “implicitly, the film says that the past and the present are one — that this horror could happen again.” Of Lanzmann, she said, “The heart of his obsession appears to be to show you that the Gentiles will do it to the Jews again if they get a chance.” Perhaps the greatest contribution of “Shoah” is a greater recognizance of the historic problem of assimilation. In 1968, Poland’s government drove up to 20,000 Jews out of the country as part of an “official anti-Semitic campaign.” But in 1986, a New York Times writer found that in Poland, “in the wake of ‘Shoah,’ attitudes on the Holocaust

seem to be changing.”

3 stars

(December 2017)

“Shoah” (1985)

Featuring

Simon Srebnik ♦

Michaël Podchlebnik ♦

Motke Zaïdl ♦

Hanna Zaïdl ♦

Jan Piwonski ♦

Itzhak Dugin ♦

Richard Glazer ♦

Paula Biren ♦

Pana Pietyra ♦

Pan Filipowicz ♦

Pan Falborski ♦

Abraham Bomba ♦

Czeslaw Borowi ♦

Henrik Gawkowski ♦

Rudolf Vrba ♦

Inge Deutschkron ♦

Franz Suchomel ♦

Filip Müller ♦

Joseph Oberhauser ♦

Anton Spiess ♦

Raul Hilberg ♦

Franz Schaliing ♦

Martha Michelsohn ♦

Moshe Mordo ♦

Armando Aaron ♦

Walter Stier ♦

Ruth Elias ♦

Jan Karski ♦

Franz Grassler ♦

Gertude Schneider ♦

Itzhak Zuckermann ♦

Claude Lanzmann ♦

Simha Rottem ♦

Francine Kaufmann (Interpreter: Hebrew) ♦

Barbra Janica (Interpreter: Polish) ♦

Mrs. Apflebaum (Interpreter: Yiddish) ♦

Charlotte Hirschhorn

Directed by: Claude Lanzmann

Written by: Claude Lanzmann

Cinematography: Dominique Chapuis Jimmy Glasberg, William Lubtchansky, Phil

Gries (documentary segments)

Editing: Ziva Postec, Anna Ruiz (Treblinka sequence)

Production Manager: Séverine Olivier-Lacamp

Production Manager: Stella Gregozz-Quef