‘American Gigolo’ shows us how just about everyone looks in shades

Julian, the lead character of “American Gigolo,” probably seems a little too unreal. Apparently coming from nowhere and lightly educated, he’s a handsome linguist whose bookshelves are lined with classics, an antique expert with street smarts who easily glides in and out of high society.

His hobby seems to be clothes, and getting dressed. He’s a little unbelievable in the mode of Will Hunting or Gordon Gekko, but that only makes him a better, not worse, movie character, one of significance who resonates to this day.

Specific occupation aside, there are indeed Julians in real life. We all probably know at least one; they are people with so much going for them on the surface that if they simply pursued conventional, law-abiding lifestyles, they'd easily get far ahead, but are somehow inclined to make things a little more difficult. Julian in fact is making money by breaking the law, but not — and this is a very important implication — in a way that seems to be hurting anyone. No one’s getting depressed; everyone’s satisfied. The artistic license of “Gigolo” is Julian’s strange devotion to his craft. He actually practices for this job.

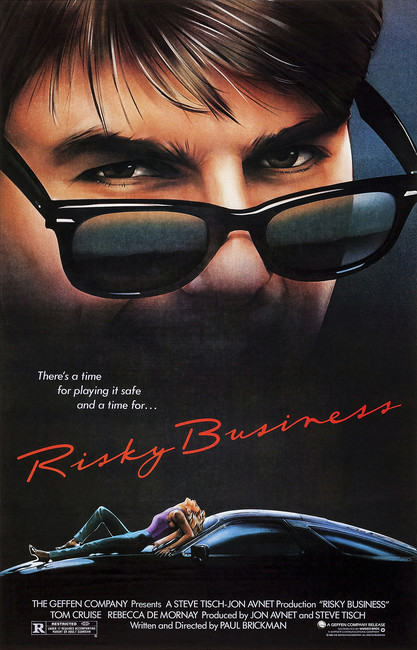

Prostitution is a fascination of directors. Godard did a bunch of films about it; you’ll find implications from Bergman, Fellini, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi. That’s hardly the extent of it. There’s “Pretty Woman,” “Risky Business,” “Midnight Cowboy.” Interestingly, some of these themes run very deep, others not deep at all; either way, as movie drama, it works. Collectively, cinema is an acknowledgment that emotional connections are often not enough to support the physical interest in the equation.

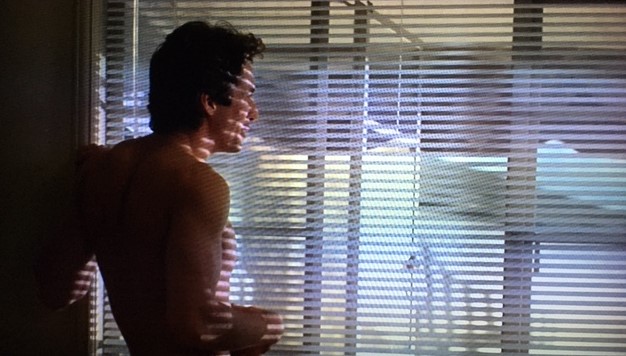

Nudity, on the other hand, doesn’t bring the same results. Many Hollywood stars refuse to do it. Those who do are generally filmed at such discretionary angles, and sometimes shown in just a fraction of a second, that the practice is cliché, a pretend unbaring of the soul that maybe doesn’t take that much guts to film and seems more about confirming an actor’s artificial artistic aspirations than advancing a movie theme.

Richard Gere, not an unknown at the time of “Gigolo” but not yet a marquee name, broke ground as certainly one of the first male actors to appear in frontal nudity in a Hollywood film. Does it matter? Pauline Kael apparently never reviewed “American Gigolo” but mentioned it in a short 1980 essay on another Paul Schrader film, “Cat People.” Neither Kael nor Roger Ebert nor Gene Siskel (the latter two each gave “American Gigolo” 3½ stars) mentioned nudity. Most viewers are probably more impressed by Julian’s workout routine, in shorts, flexing 6-pack abs upside-down in a curious apparatus in his apartment.

It would seem Schrader and Gere have fallen for cliché. Gere hops out of bed and stands sideways, pretending to look at something out the window so that viewers and Hutton can get a glimpse, shaded by the blinds that so fascinate Schrader throughout this film (to the point of absurdity), while Julian complains of a client that “it took me three hours to get her off” and what other servicer would’ve “cared enough to do it right.” The nudity in the scene lasts about 54 seconds, longer than most examples, but the only real “visible” portion is about 11 seconds.

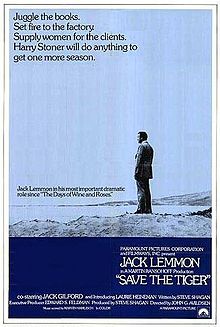

Hollywood to this day struggles with the significance of nudity. Rather than depicting a character’s vulnerability, it seems more about satisfying an actor’s bucket list. (One bizarre example is Jack Lemmon behind a frosted-glass shower door in “Save the Tiger.”) When does nudity really “work” in a non-pornographic film? It may be assumed that an undeniable arthouse classic, Bergman’s “Summer with Monika,” was only seen in the United States because Kroger Babb, the showman who acquired the U.S. rights, trumpeted the nudity and renamed it with a bad-girl label. Tiny glimpses of famous American actors hasn’t seemed to produce the same box-office lift. Despite decades of sexual liberation, “pornography” is very much a toxic label for Hollywood, perhaps the stars even more than the producers.

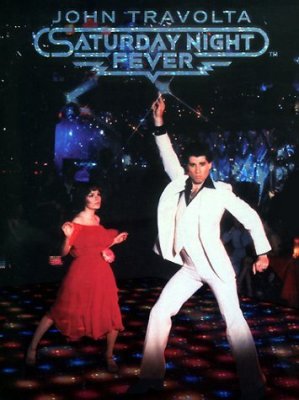

The lead role of “American Gigolo” originally belonged to John Travolta. Gene Siskel wrote that Travolta exited because of the death of his mother and “the box office and critical failure of ‘Moment by Moment.’ ” (Travolta unluckily picked the wrong one. “Moment” has a similar setting to “Gigolo” and actually occurred during Travolta’s peak, and yet you’ve likely never heard of it.) (Somehow, according to at least one report, Chevy Chase was offered the lead role of “Gigolo” in between Travolta and Gere.)

Maybe, had he kept the “Gigolo” role, Travolta might’ve done the nude scene that Gere did. Except he could’ve done it in “Saturday Night Fever” and appears in underwear instead. Maybe Travolta had more to lose, or Gere had more to gain. Or maybe it’s irrelevant.

“American Gigolo” is a Paul Schrader film, which means it’ll always be compared with “Taxi Driver.” But there’s at least one big difference. “Taxi Driver” is an undeniable ’70s film. “American Gigolo” is surely an ’80s film and a very white-European one. Its characters (even the politicians) are not concerned with Vietnam or trust in government. Rather, it’s about credit cards, conspicuous consumption, Armani suits, cocaine, late-model luxury cars, stereos, the latter briefly offered as a bargaining chip (but “I got a stereo”). That Schrader put this together just before the ’80s even got here shows his prescience. (One character does take a stab at fossil fuels, yes, a perennial California fascination. And there is a weak jab at government surveillance.)

It would take years for the ’80s to be cemented as the Decade of Greed, but there is enormous cynicism in “Gigolo.” Dating occurs for financial reasons only. Everyone taking part in this landscape is compromised in some way. A politician apparently has not done anything wrong, except that his wife is tired of him, and there’s something lovely about her, so it must be his fault. His response is to attempt to buy his way out of this problem.

Cynicism extends to the notion of whether Julian might be gay. He pretends to be, in one curiously confusing scene that develops so quickly in which characters hurriedly explain to each other (for the benefit of viewers) why they’re putting on this gag. Richard Gere in 2012 said he became interested in the script partly because “There’s kind of a gay thing that’s flirting through it and I didn’t really know the gay community at all.” Throughout the movie, Julian insists he doesn’t do gay business even though the movie suggests constant demand for it, though by the end, he indicates that he’s open to the possibility under duress, not unlike Dirk Diggler in “Boogie Nights.” There’s a heavily implied stigma. We are led to believe that older single, lonely women are the wealthiest people in the world, also they can’t achieve the big “o,” that’s why Julian prefers that demographic, but maybe there are deeper reasons.

Movies are chock-ful of Couples Who Aren’t Really Believable As Couples. Lauren Hutton’s Michelle and Julian are basically in that category, though it’s not one of the worst examples. Viewers never learn who she is or where she’s from because Julian frankly doesn’t care. But an even more unbelievable couple is Lauren and her husband Charles, the senator. Charles seems like a B- or C-grade politician and will not receive much screen time, so we must be told by characters that he is actually “a real comer” (that’s mentioned twice).

Pauline Kael writes that Julian is “redeemed by love.” Michelle must be one of countless women who’ve noticed Julian and expressed interest. She’s seduced by him like all the others. But the movie decides this can be a coming of age, she is the guide who will make him see the light, realize that women are people to share life with, not finance your wardrobe.

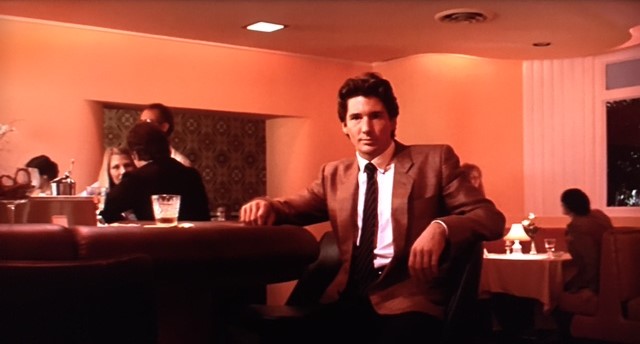

Schrader introduces Julian and Michelle at an elite restaurant. He only notices her after first assessing another table. When he approaches the table of Michelle, he is standing, she’s seated. Who has the upper hand, who is vulnerable?

Hutton, in probably some of her best acting, impressively in the “meet cute” takes us through the discovery process. She seems to be hoping a man will approach her, but when Julian does, she doesn’t quite know what to say. At first she will pretend she is waiting for a friend, then, after a couple moments of fascination, freely admits there is no friend coming. The scene lasts nearly five minutes. The conversation that Julian has quickly deemed a waste of time is enjoyed by Michelle, that’s why she’s disappointed when he says “I made a mistake” after hearing about her husband.

What caused Julian to say yes? He’s not hit by a thunderbolt; he writes Michelle off. It’s only after she comes to his home and virtually begs for a one-night stand — not that much different from Donna Pescow’s Annette in “Saturday Night Fever” — that he seems slightly taken. Pity? Maybe, or perhaps a fascination at how desperate she seems to be to consummate this relationship. Probably in most films, these roles are reversed, a man blatantly attempts to win over a woman. Roger Ebert observed, “This business of redemption would work better if ‘American Gigolo’ had at least a few more scenes developing the relationship between Gere and Hutton: Her character ... isn’t seen clearly enough.” Michelle is notably younger than Julian’s clients but still older than Julian, which perhaps is a necessity. Gere was about 30 during filming; Hutton is six years older.

Too much of the plot-moving events in “American Gigolo” occur off-screen, but Schrader correctly determines that all the intimate moments with clientele should be among them. There’s no need to show Gere making out with a woman at least twice his age. Rather, it’s the demand that Julian inspires that makes “Gigolo” repeatedly watchable. Unlike Siskel and Ebert, Pauline Kael wasn’t terribly impressed, calling the characters “enervated” and the film “stagnant” and “logy” (you might need an online dictionary for a couple of those).

Kael shrugged that no one gives his films a “tonier buildup” than Paul Schrader, but “his movies are becoming almost as tony as the interviews.” She complains, without further clarification, that Schrader “doesn’t shape his sequences” and that the “only energy” of “American Gigolo” is in the Blondie hit theme song “Call Me.”

Does “American Gigolo” make a case against criminalizing vice? Julian on more than one occasion touts the value of his service, as though part of the justification is that he cares about what he’s doing. It seems his chief professional offense, the source of the film’s plot, is that he is working independently in a field in which middlemen, who care only about the bottom line, seem to think their services should be exclusive. This prevents Julian from receiving the film’s macguffin — an alibi — and seeking one from the real culprits certainly seems not the smartest move.

Hector Elizondo, as the vice cop Sunday, earned significant praise from Ebert. Fine, but Sunday is little more than a typical Hollywood cartoonish characterization of a police investigation. Elizondo is whom Ebert would call the Reliable Observer. He’s needed to tell the audience about Julian’s background and also about what really happened in this mysterious death. However, he will also declare that Julian is “guilty as sin,” and we don’t know if that’s the truth about the killing ... or something else.

Gere tells Sunday he’d like to help more, but “These are very delicate matters.” One thing the movie tells us is that doing something illegal — even if no one really cares that it’s illegal — puts a person, however otherwise upstanding, in a vulnerable situation. Given his profession, Julian is never going to be out of work for long; still, being falsely accused of a serious crime should be enough to prompt someone of Julian’s means to hire his own investigator to get to the bottom of this. His lawyer seems well-heeled but not the least bit interested in what really happened in this case. Is Julian overconfident because he knows he’s innocent? Or because everything simply comes easy to him?

There is an inevitable Catch-22 about Julian that the movie has to ignore, or else there’s no movie. If he were really able to connect with a woman on a real level, he wouldn’t be doing what he’s doing. This was only Gere’s first experience with this kind of cinematic stretch. Like “Pretty Woman,” it’s a hooker with a heart.

3.5 stars

(May 2023)

“American Gigolo” (1980)

Starring

Richard Gere

as Julian

♦

Lauren Hutton

as Michelle

♦

Hector Elizondo

as Sunday

♦

Nina Van Pallandt

as Anne

♦

Bill Duke

as Leon

♦

Brian Davies

as Charles Stratton

♦

K Callan

as Lisa Williams

♦

Tom Stewart

as Mr. Rheiman

♦

Patti Carr

as Judy Rheiman

♦

David Cryer

as Lt. Curtis

♦

Carole Cook

as Mrs. Dobrun

♦

Carol Bruce

as Mrs. Sloan

♦

Frances Bergen

as Mrs. Laudner

♦

MacDonald Carey

as Hollywood Actor

♦

William Dozier

as Michelle’s Lawyer

♦

Peter Turgeon

as Julian’s Lawyer

♦

Robert Wightman

as Floyd Wicker

♦

Richard Derr

as Mr. Williams

♦

Jessica Potter

as Jill

♦

Gordon Haight

as Blond Boy

♦

Carlo Alonso

as Salesman

♦

Michael Goyak

as Jason

♦

Frank Pesce

as Suspect #4

♦

Judith Ransdell

as Cloak Room Girl

♦

John Hammerton

as Perino’s Maitre d’

♦

Michele Drake

as 1st Girl at Beach

♦

Linda Horn

as 2nd Girl at Beach

♦

Faye Michael Nuell

as Woman at Juschi’s

♦

Eugene Jackson

as Bootblack

♦

Roma Alvarez

as Maid

♦

Dawn Adams

as Coed

♦

Bob Jardine

as College Professor

♦

Harry Davis

as Parke Bernet Representative

♦

Nanette Tarpey

as Waitress

♦

Maggie Jean Smith

as Girl at Daisy

♦

Pamela Fong

as Girl at Daisy

♦

Randy Stokey

as Boy at Sorel

♦

Harris Weingart

as Maitre d’ Cocktail Lounge

♦

James Currie

as Bartender Cocktail Lounge

♦

Norman Stevans

as Waiter Cocktail Lounge

♦

Betty Canter

as Woman at Political Dinner

♦

Laura Gile

as Woman at Political Dinner

♦

Brent Dunsford

as Man at Political Dinner

♦

Barry Satterfield

as Street Hustler

♦

Sam L. Nickens

as Waiter Country Club

♦

William Valdez

as Prison Guard

♦

Mary Helen Barro

as Reporter

♦

John H. Lowe

as Reporter

♦

Kopi Sotiropulos

as Reporter

♦

Gordon W. Grant

as Reporter

♦

Ron Cummins

as Reporter

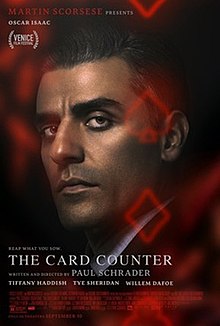

Directed by: Paul Schrader

Written by: Paul Schrader

Producer: Jerry Bruckheimer

Executive producer: Freddie Fields

Music: Giorgio Moroder

Cinematography: John Bailey

Editing: Richard Halsey

Casting: Vic Ramos

Art direction: Ed Richardson

Set decoration: George Gaines

Makeup and hair: Chris Lee, Dan Striepeke

Unit production manager: Neil A. Machlis

Stunts: Jeoffrey Brown