‘Saturday Night Fever’ is the

Steph that dreams are made of

Sometimes, human beings can learn important things from people who shouldn’t be capable of teaching them.

“Saturday Night Fever” has just such a message. The hero, Tony Manero, is in dire need of ambition. Where does he find it? From a woman who is nearly a complete phony. Does that negate the wisdom she imparts? No, because maybe ambition is something that can’t really be taught, only realized.

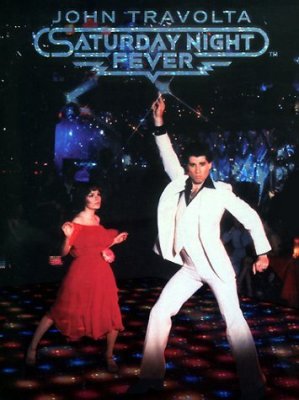

Many think of “Saturday Night Fever” as a celebration of disco and not much more. It arrived in 1977, possibly after disco’s peak. In interviews, the producers and director John Badham point out that there was a fear during the filming that the disco era was over, that the movie would be yesterday’s news once released.

It wasn’t — it opened to massive popularity, and, thanks to several big hits from the Bee Gees, made musical history. But it’s probably fair to say the rapid demise of disco by around, say, 1980, and the even more rapid demise of the career of John Travolta shortly after threatened to make the film a permanent butt of leisure-suit jokes.

It was based on a compelling 1975 New York Magazine article by Nik Cohn about a fictional young, blue-collar man who owns the dance floor on weekends. The film’s producer, Robert Stigwood, is credited with preserving the grittiness of the story for the movie. A script Hollywood might’ve twisted into light dance fare instead famously addressed issues of extreme racial prejudice, outrageous sexism and intense vulgarity.

That script isn’t as good as the dancing. Those who get nothing out of the story will at least feel energized every 15 minutes or so by the nightclub scenes. (The lighted “Saturday Night Fever” dance floor is so popular, it sold at auction in 2005 for $188,000.) The plot doesn’t quite have all the moves, but there is meat here.

Tony’s world is the Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn, not necessarily a bad setting for this type of message, though people from there might object to its status as nowhere land in this film. (Among its famous natives is CNBC star Maria Bartiromo, who made the type of leap to Manhattan that Tony and Stephanie can only dream of.) In a couple instances, bridges to Manhattan are shown, impressively, and it will take more than a car (something Tony doesn’t have) for Tony to get there.

Bay Ridge is depicted as a working-class Italian neighborhood, with Latino influx. Almost immediately, the bigoted nature of Tony’s gang of friends is evident. They certainly don’t like Latinos and blacks, or gays, and they’re not going to be honored by NOW anytime soon. They might, or might not, hold jobs, and only one of them has a (beaten) car.

They are more or less good-for-nothing. Except for one thing: They can dance. Especially Tony.

Best actor nominee John Travolta at the 1978 Oscars.

John Travolta, as Tony, has a challenging assignment. He is a regular person who 1) must be king of a tiny little world, and 2) already knows from the beginning of the picture that ultimately this world is a dead end, and he must move on. Travolta passes the first test with jaw-dropping excellence, only to be hampered by the troublesome script in his march to Manhattan.

The opening scenes accomplish three important goals: We hear the famous soundtrack, we see that this film is about the grittier portions of New York City, and within moments we know all about Tony. He hauls paint cans around (low-paid, lightly educated), eats pizza rather indelicately (unsophisticated), doesn’t have enough money to buy a flashy shirt, flirts relentlessly, and charms his way out of sticky conversations.

An early little scene in the paint store serves as a warning. Tony has arrived a bit late from his assignment — filling a customer’s paint order from a rival shop — angering his good-natured boss, Mr. Fusco, but he engineers a little boss-approved chicanery to make a healthy profit from an irritated customer (played by John Travolta’s mother, in fact). Then he makes friends with a different customer, and the shop is seen as a likable neighborhood establishment. But at the end of the day, Fusco closes the place with the type of heavy gate that is commonplace in many parts of big cities. The world is still a dangerous place. Fusco and Tony chat briefly about the future. “The future ... catches up with you, and (expletive) you if you ain’t planned for it,” he tells Tony.

It may be tough to convince Tony, though, because he has a great thing going on the dance floor at the nightclub 2001 (a year that must’ve seemed so far into the future when this film was released). A few of cinema’s most memorable scenes occur here. The first is when Tony leads his crew into the club, to the sounds of “A Fifth of Beethoven” (the disco version of the symphonic smash). “You guys have the Moses effect,” Tony’s brother Frank will say, and the regulars are seen clearing out to let Tony through, shake hands, slap him on the back, and escort him to the table they’ve reserved for him. The second occurs later when Tony clears out the lighted dance floor and Travolta performs his unforgettable, mostly uncut disco routine to “You Should Be Dancing,” a scene that incredibly was doubted by director John Badham and (supposedly) only reinstated at Travolta’s insistence.

But always, the music will finally stop, and we’re back to another day, another week on the job, perhaps another week of going nowhere.

Tony’s circle of friends, and even his parents, seem content with this lifestyle. His family is blatantly sexist. At one point Tony is about to clean the dinner table when his father says, “Girls do that.” Around the dinner table, they are proud and close-knit and seemingly of high character, but can’t avoid screaming at each other and slapping each other on the head. Tony at one point volunteers that his father doesn’t think he is good for anything, and his father does not disagree.

Notice that Tony comes from a religious, two-parent family and not a broken home. It seems that in the filmmaker’s mind, the problem isn’t the family structure, but Bay Ridge. Everything in this Bay Ridge is toxic; you don’t want to be there under any circumstances. Get out while you can, while you’re young and can do something about it. This sweeping generalization preys succesfully upon people’s most outrageous beliefs about geography, that our own surroundings can be blamed for destroying our potential and that where we live or where we’re from determines in part whether we’re better than someone else.

A more realistic film, and message, would be someone persuading Tony not to follow a phony to Manhattan, but to make something of himself where he’s comfortable, in Bay Ridge or elsewhere. Why doesn’t he, for example, teach dancing? Surely women would pay a premium to learn from him. If he’s not comfortable with that, he should be comfortable with the paint shop. He is well-liked there. He could be a manager soon, there or somewhere else; maybe save his money and open his own place.

Those thoughts never cross Tony’s mind. The script never lets Travolta get that far, and that is a problem. If it did, we’d have a different movie.

So back to the movie we’ve got.

Tony’s frustration, and disdain for Bay Ridge, is ramped up when he sees Stephanie on the dance floor at 2001. The first thing we notice about Stephanie is that she doesn’t look like the other women at 2001. She is more reserved, formal, professional, austere, proud.

Tony is not accustomed to this type of woman. He is regularly hit on by others not as elegant, and he has grown to disdain them. When Stephanie enters his world, briefly, he is actually impressed, and his confidence is diminished around her. This is expertly shown in their scenes together as Tony attempts to cover his awkwardness with charm.

The only problem with Stephanie is that the more we see of her, the less we like. Presumably, Tony should feel the same way, but he doesn’t. Stephanie is played by Karen Lynn Gorney, an unknown and relative newcomer at the time who faded away after the movie. Apparently big things were expected of her, because she is given the “introducing” description in the credits. She doesn’t seem to be a great actress, and that’s probably a good thing here as we gradually see her unable to convince even Tony of who she really is.

We begin to see Tony pulled in two directions, from his small-minded friends who offer no future, and Stephanie, whose pronouncements seem more and more bogus. This obviously correlates with another Travolta megahit of the time, “Grease,” in which a teen chooses between his buddies and a girl.

In a climactic moment, leaving 2001, Tony could seal the deal with Bay Ridge and depart with Stephanie, leaving his buddies behind. But instead he attempts to treat Stephanie like he and his gang typically treat women. Stephanie objects and leaves. Rather than follow, he rides home with his buddies, only to witness tragedy, and then we see him visually turn his back on them, en route to the future.

Tony’s tragic friend, Bobby C., played by Barry Miller, who was the only pro actor in the group of Tony’s friends, is a great character in a woefully undeveloped role. Bobby C. is the prototype of a guy who doesn’t belong in the clique. During his scenes you want to scream at him, “Why are you hanging out with these people?!!” Well, we know why. Socially, they are superior to him, and like most people he wants to maximize his social potential. So why would they give him the time of day? Because he’s got a car. He is, in fact, being used, and getting nothing but scorn or pity in return, and totally accepting of this arrangement. It is difficult to believe his fate — supposedly the last straw for Tony — would trigger in this group anything beyond crocodile tears. Such a tragic figure, so Bay Ridge.

Tony’s brother Frank Jr., played by Martin Shakar, is there to show us how unreasonable the Manero parents are. They believe Frank is great, because he is a priest. But as Frank explains after quitting and returning home, “All I ever really had a belief in was their image of me as a priest. That’s all.”

This is a sign to Tony not to believe his parents’ expectations. Of course, it’s also another signal to get out of Dodge, as Frank Jr. does. His brief depiction might work better if the two were actually believable as brothers. Shakar better resembles Alan Alda than John Travolta and comes across as completely white-collar — and we don’t mean the kind a priest wears. At least it is believable why he returns home to scorn in the first place — he doesn’t have any money — and after a couple weeks or so is most eager to move on.

But neither Frank Jr. nor anyone else seems to care about Tony’s future as much as Stephanie, and she earns points for that. Her issues actually help bolster Tony’s character. For one thing, we see he is honest, especially compared with her. When they meet at a diner, she’s tea, he’s coffee, and they compare notes on life. She boasts that the people she works with are “not like these Bay Ridge people at all ... people are beautiful, offices are beautiful. Nobody has any idea how much I’m growing.” She mentions Laurence Olivier dropping by and later drops names like Paul Anka and Joe Namath.

Tony reluctantly tells it like it is. “I work in a paint store,” he says, to which she replies, “You’re a cliche.” She’s harsh, but unfortunately, correct. She knows his routine and can confidently declare “You’re nowhere, on your way to no place.” But she isn’t completely negative. She asks, “Did you ever think about going to college?” Tony may be unimpressed by her empty boasts, but her ambition has him hooked.

Stephanie’s world cracks when Tony helps her move. He is fired by Fusco for taking the afternoon off, but that’s not such a bad thing, as maybe he’s finally crossing over into Manhattan for good with Stephanie. But once they get there, the facade disintegrates. Stephanie has apparently been living with a much older man who thinks little of her. He mocks her for using the word “super,” in the same way she would criticize Tony.

When she bursts into tears in the car, she has hit rock bottom, and Tony’s sense of this is one of Travolta’s strongest scenes in the movie. And when Tony is welcomed back by Fusco, it’s even a hint that Bay Ridge isn’t so bad. It all sets the stage for their climactic moment in the car at night and at her apartment the next morning, when Stephanie says she hangs out with him because of “dancing,” and then later admits, “You made me feel better, give me admiration, respect, support.” And so they agree to be friends, and so in the end Tony has conquered at least one of his vices — sexism.

In all of this review, precious little has been said about the music. That is because music can’t adequately be described in print. Yes, it is unquestionably a musical as well as an urban coming-of-age story. Perhaps this should say in the first paragraph, “The music’s great. Don’t miss it.” A lot of people claim to loathe disco, a few actually do. Once the fever had broken by the very late ’70s, it took a while before these songs were heard on radio again, but just check the sales of the “Saturday Night Fever” soundtrack for an indication of their staying power.

Badham employs a nice balance between the songs and the grit. The soundtrack is heavily used early — four landmark songs, “Stayin’ Alive,” “A Fifth of Beethoven,” “Night Fever” and “If I Can’t Have You” are heard in the first 25 minutes — and nicely paced throughout.

Most associate the film with the Bee Gees, but the soundtrack is diverse. The Bee Gees had already been popular in the ’60s and experienced a revival from the songs in the movie. Incredibly, the music was a very distant production; the Bee Gees churned out the singles from France while working on an album, but they are so closely tied to the film that they feel like they were penned spontaneously on the set of the dance floor. The band, for its part, refused to be the only group on the soundtrack, which opened the door to hits like “Disco Inferno” and the sizzling “K-Jee,” used during the most brilliant dance of the movie.

Badham had one film on his resume before being summoned as a pinch-hitter. The magazine article had drawn Hollywood interest, and Stigwood initially employed a hot director, John G. Avildsen, who was about to collect an Oscar for “Rocky.” But Travolta, white hot at the time as a TV star and seen as an obvious choice to play Tony, clashed with Avildsen over the nature of Tony’s character. Stigwood yielded to Travolta — the first of many times that would happen — and fired Avildsen, and Badham for some reason got the call, on very short notice.

In director commentary, Badham notes the difficulty of putting the movie together. Travolta’s girlfriend, actress Diana Hyland, whom he met while filming “The Boy in the Plastic Bubble” (she was 18 years his senior) and who originally played the mother in “Eight is Enough,” was ill and died of cancer during the “Fever” shooting. Other setbacks came from the neighborhoods, where crowds of teen fans of Travolta prevented filming, and organized crime figures threatened trouble unless protection payments were made.

Badham’s only major point of controversy was his apparent decision to cut down Travolta’s epic solo dance into a series of close-ups. Travolta tells of being aghast when seeing the “final” cut of the film and demanded to re-edit the dance scene himself. He was accommodated, something Badham probably doesn’t regret today. “Saturday Night Fever” is among a highly select club including “Star Wars,” and perhaps “Jaws” and “The Godfather,” of 1970s films where theatergoers would emerge afterwards, stunned, wondering, “What did I just see?”

Badham says he didn’t get a couple scenes he really wanted. One of them might’ve been an understatement. He talks of wanting to show the dance hall at closing time, when the house lights go on, the floor lights go off, the music stops, everyone remaining groans, and the party abruptly ends. No doubt this is a powerful image and one we’ve all felt at a club or bar somewhere when we’ve been having too good of a time.

“Fever,” though makes that point clear for two hours. Sometime, the music is going to stop. The success of Tony is, he knows it.

4 stars

(October 2008)

“Saturday Night Fever” (1977)

Starring John Travolta as Tony Manero ♦ Karen Lynn Gorney as Stephanie Mangano ♦ Barry Miller as Bobby C. ♦ Joseph Cali as Joey ♦ Paul Pape as Double J. ♦ Donna Pescow as Annette ♦ Bruce Ornstein as Gus ♦ Julie Bovasso as Flo Manero ♦ Martin Shakar as Frank Manero Jr. ♦ Sam J. Coppola as Dan Fusco ♦ Nina Hansen as Grandmother ♦ Lisa Peluso as Linda Manero ♦ Denny Dillon as Doreen ♦ Bert Michaels as Pete ♦ Robert Costanza as Paint Store Customer ♦ Robert Weil as Becker ♦ Shelly Batt as Girl in Disco ♦ Fran Drescher as Connie ♦ Donald Gantry as Jay Langhart ♦ Murray Moston as Haberdashery Salesman ♦ William Andrews as Detective ♦ Ann Travolta as Pizza Girl ♦ Helen Travolta as Lady in paint store ♦ Ellen March as Bartender ♦ Monti Rock III as The Deejay ♦ Val Bisoglio as Frank Manero Sr. ♦ Roy Cheverie as The Wrong Partner ♦ Adrienne King as Dancer ♦ Alberto Vazquez as Gang Member

Director: John Badham

Written by: Norman Wexler

Written by: Nik Cohn (magazine article)

Executive producer: Kevin McCormick

Producer: Robert Stigwood

Associate producer: Milt Felsen

Original music: Barry Gibb ♦ Maurice Gibb ♦ Robin Gibb

Cinematography: Ralf D. Bode

Editing: David Rawlins

Casting: Shirley Rich

Production design: Charles Bailey

Set decoration: George Detitta

Costume design: Patrizia Von Brandenstein

Makeup: Henriquez ♦ Joe Tubens

Stunts: Paul Nuckles ♦ Lightning Bear