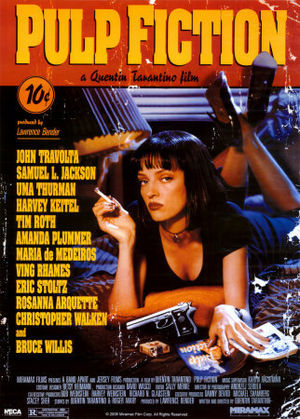

The truth about the ‘Fiction’:

An unspeakably funny film

Perhaps a review of “Pulp Fiction” should have the paragraphs rearranged as a form of reverence.

It would be way too much fun. But then people wouldn’t figure it out, a lot of them would click on to another Web site, and all of the observations that required a lot of mental rewinding and fast-forwarding would be lost.

The “Fiction” is a great movie yearning to be a B movie. It has the feel of the type of schlock usually reserved for local independent TV stations around 2 a.m. Sunday. Confusing? Yes. Filthy? And then some.

No question it taps into the healthy public appetite for carnage. This appetite is stronger than many serious movie-goers would like to admit. Some who saw this one, because of the extensive critical praise, walked away completely disgusted.

The “Fiction,” though, isn’t bad gore, but good gore. One line after another is hilarious. It’s reverential treatment of the type of mayhem seen in gangster or martial arts B movies. It can be laughed at here not only because it’s funny, but because it illustrates a story that really does have a heart. And those who watch closely will realize that most of the violence is offscreen and only talked about, with barely even a hint of sex.

Does that mean everyone should like it? No. It does mean that those who enjoy, or at least can tolerate, depictions of bloody faces, heavy drug use and the “n” word and “f” word and “b” word and all kinds of sexual and sexist descriptions over and over are in for a treat.

“Pulp Fiction” is essentially about a hit man who is beginning to question his life’s work. This is hardly the only film attempting to tell such a story. But none of the others have ever told it quite like this.

Unimpressed viewers think the scenes are out of sequence because the director enjoys fooling with them. In fact, the film is in order in terms of plot. Characters experience the right situations at the right times. No character is introduced out of sequence. All are initially shown in their normal, everyday lives before being given a problem.

The movie opens, as some do, with a preview of the climactic scene. (For example, Johnny Cash warming up his guitar at Folsom Prison in “Walk the Line” just before we’re taken back to his childhood.) Here we have a couple in a diner discussing the possibility of committing a serious crime. What they say is funny: “Nobody ever robs restaurants ... betcha you could cut down on the hero factor.” But just before we learn the outcome of their discussions, we’re zapped away, into a completely different world that won’t come full circle for another couple of hours.

The story centers around Jules Winnfield, played by Samuel L. Jackson, and fellow hit man Vincent Vega (John Travolta). The two are introduced as equal partners, but from the beginning we see a major divergence coming.

Vincent is oblivious to the larger issues in life. Jules, though, is having second thoughts about things, and is complemented by a couple of other characters, only linked very loosely, who are also dealing with issues of judgment. One is a boxer, Butch, with a complicated values system. Another is a young woman, Mia, who has probably gotten a decade ahead of herself, and not in a good way.

Collectively, the latter three deliver a stunning repudiation to the man at the center of their world, Marsellus, a crime boss who himself is not completely unsympathetic.

Jules and Vincent are depicted as quality professionals. It’s very early morning, yet they’re dressed in formal work attire, they’re sober, they’re on time, they’re prepared for work.

They are performing homicidal enforcer activities that are so routine for them they aren’t the least bit nervous.

Vincent spends much of his screen time, including his first scenes, talking about Europe. He speaks of Europe not like many Americans who study the Renaissance and French Revolution and dream of visiting Paris and Rome, but as a lightly educated person who only views it as “different.” He doesn’t even know what a TV pilot is.

Vincent casually asks Jules what he knows about Marsellus’ “new bride,” Mia. Jules explains she’s a B-level actress. But he goes on to explain how Marsellus harmed a man named Antoine who supposedly gave Mia a “foot massage.” To Vincent, the alleged transgression at least partly justifies Marsellus’ response. Vincent, a savage killer, would later complain to an acquaintance about someone keying his expensive car. He sees this as certainly not karma catching up with him, but an unpardonable offense against society. “Don’t (expletive) with another man’s vehicle — it’s against the rules,” he grumbles.

But Jules mildly condemns Marsellus, assuming the story is even true. This provides an early divergence between Jules and Vincent and a plot catalyst, as Vincent reveals he’s going to be the next man to spend time with Mia, on the request of Marsellus himself, who according to Vincent wants him to “take care” of his wife while’s he’s gone.

Jules raises his eyebrows, and Vincent protests: “It’s not a date ... definitely not a date.” The subtext is clear, that Vincent isn’t trying to convince Jules, but himself, because he is suddenly aware that if it turns out he’s wrong, what happened to Antoine could happen to him.

Jules, though, has his own demons. The pair’s assignment is to retrieve a briefcase and punish the people who kept it. They encounter a roomful of scared, inept-looking young men. Jules does all the talking, hilariously, about one of the film’s favorite subjects, fast food, until the men eagerly cough up the briefcase.

The briefcase lock opens to 666. Inside is some kind of macguffin. It is something glowing that belongs to Marsellus. The message is obvious, whoever wants this case is selling their soul. Once the briefcase is opened, the shooting starts, and Jules is transformed, from a funny, easygoing man into a murderer.

Our introduction to Butch is also our introduction to Marsellus. They’re conversing at an empty nightclub in the daytime, and we know from a host of other films (“Urban Cowboy,” “Road House,” “54,” et al.) that only bad things happen in nightclubs during off-hours. Some kind of orange, glowing light similar to what was in the briefcase emanates from Marsellus and around the club. Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” is playing while Butch takes Marsellus’ money and promises to take a fall in the fight. But does he really promise? It seems like the whole scheme is really Marsellus’ idea.

The scheme poses a question: If you’re trying to fix a fight, should you pay off the boxer beforehand — or not until the fight’s over? It makes sense that you would pay in advance, to ensure the boxer’s loyalty before you place your bets on the fight. But then we see how Butch can dupe Marsellus on several levels, taking the upfront cash, leaking word that the fight is fixed, betting on himself to win, then winning and skipping town.

Butch might be an ordinary con artist, but he’s motivated by a powerful memory. He recalls hearing a soldier, played by Christopher Walken, tell him, as a child, how his father and grandfather suffered in war to protect a watch. Like many scenes, it is highly poignant until devolving into outrageous humor. The end result? The watch is now in the hands of Butch, after great sacrifice.

This scene, as a flashback, is set up very neatly. Initially we’re led to believe that Butch suddenly changes his mind about throwing the fight after recalling the sacrifices of his father. But later it is clear that Butch never was going to take a dive. Instead, the Walken flashback sets up a more important scene minutes later — Butch will risk his own life not for money, but to save the watch. This is an example of the type of unexpected twists director Quentin Tarantino thrives on.

Retrieving the watch delivers an unexpected benefit for Butch. He is forced to encounter his nemesis, Marsellus, and when the two of them end up in a most precarious situation, he is compelled to do the right thing and save Marsellus, though that means putting his own life at risk.

During this episode, Butch puts an end to the Vincent Vega story.

John Travolta has star billing. It’s likely he has the most screen time. Yet Vincent is also the most unfortunate of the main characters. Why? The message seems clear: He didn’t repent.

Vincent’s story is told through his non-date with Mia. He is dense, so it doesn’t occur to him to question why Marsellus has asked him to escort his wife. Mia seems not so much Marsellus’ wife as his kid sister. Maybe Marsellus wants Vincent to protect her when he himself can’t be around ... or maybe he wants her occupied so he can fool around.

Uma Thurman and John Travolta converse in their restaurant scenes not as confident adults, but shy teenagers. In a series of delicious dialogue, Vincent first orders a steak “bloody as hell,” with a “vanilla Coke.” Mia then tells of her experience in a TV pilot and says her specialty in “Fox Force 5” was “knives” — all a hilarious foreshadowing of the stabbing fate headed Mia’s way.

But as they fight through the awkwardness, we see Mia is not only lovely, but a beautiful dancer with a charming sense of humor. We would gladly take her home ourselves, but for her vice. She’s trouble, of the self-inflicted kind. Once home with Vincent, she begins to dance to — from a reel-to-reel tape — an Urge Overkill version of the haunting Neil Diamond classic, “Girl, You’ll be a Woman Soon.” And within moments, this dazzling woman is reduced to a ghastly, comatose junkie whose rescue is performed under the most hilarious of conditions by Lance, Vincent’s drug dealer played by Eric Stoltz. What was a wonderful date has gone horribly awry.

The implication is that Marsellus has treated Mia as a spoiled child. Once she overdoses, Vincent hauls her into the car and speeds over to Lance’s house. Between the phone call from the car and the arguments at the house, Mia is referred to as “chick,” “girl” and the “b” word — never “woman.”

Stoltz pulls off a scene that is fall-out-of-your-chair funny. He watches slapstick comedy at 1:30 a.m., argues with his wife, wears a bathrobe around the house all day. But it’s the tiniest gestures that deliver the most. His eyes lighten during the phone call when it occurs to him Vincent is on a cell phone. Then he stands at his front door, rolls up the shade, stares at the car screeching across his lawn, suddenly jolted into a cringe when the car crashes into his garage. From there it gets even better, the situation and the arguments are kicked up a few notches, and it would be too time-consuming to list all of the lines during the adrenaline shot, but Lance’s wife’s “That was (expletive) trippy!” caps it perfectly.

Vincent’s actions during this ordeal are entirely about self-preservation. He became mildly interested in Mia, but only as a possible one-night stand. He feared her death not because he cared if she lived or not, but because unlike Butch and Jules, he presumed the worst in people, that Marsellus would certainly blame him for it and his own career, or life, would be at risk. He doesn’t bother to take her to a hospital, where police might ask questions, but to a dealer’s home for a less-than-reliable remedy.

Vincent and Jules are initially seen in their work clothes — black suits, white shirts, black ties. In a key moment, they must discard these uniforms for silly looking T-shirts and shorts. Soon, we see Jules freely embracing his newfound life and appearance, unencumbered by the moral demands on a hit man. From Butch’s story, we have already seen that Vincent will go back to donning the attire of doom, and suffer the consequences.

Tarantino, already on the map with “Reservoir Dogs,” achieved permanent fame here. He has a gift for keeping the action unpredictable. He uses a combination of humor and grotesque violence to pull U-turns on compelling scenes. A little of the violence can rightfully be labeled a crutch. The humor though is original and off-the-charts. Most scenes involve forays into deep seriousness, only to climax either in an outrageously raunchy joke or visually alarming assault. A lot of situations occur in bathrooms. People get their heads blown off, and you can’t help but laugh.

He also, with complete success, dabbles with visually powerful elements that illustrate the bizarre world of the characters. Everyone drives notorious cars that are decades old. The haircuts may be from the ’70s ... or the ’60s ... or even the ’50s. Most curiously are the eating establishments. These are not the diners of, say, “Five Easy Pieces” and “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore” and about 500,000 other films, where people sit close to each other and things bustle; these are wide open, low-key settings where even the waitstaff barely intrudes, a sign of the characters occupying their own little worlds.

Finally there is a remarkably seamless interaction between black characters and white characters. This is another element Tarantino uses to defy convention and steer far away from predictability. Blacks and whites partner in almost every venture in the film. Certainly there must be an expectation of racial tension somewhere along the line, maybe not what we get in “Crash,” but some clever scene here and there pointing out the little nuances. No. Marsellus asks Butch, “You my n-----?” Butch replies without reservation, “Certainly appears so.”

Should the “Fiction” have won the best picture Oscar? On filmmaking merits, yes; on public tolerance, probably not. It lost to “Forrest Gump,” a standard story featuring a star who was white hot in Oscar-land at the time. It was also nominated against “The Shawshank Redemption,” another film that enjoys long-term staying power.

“Pulp Fiction” unfortunately requires a few too many qualifiers to be fully appreciated. For some, the racially tinged, explicit language is a non-starter. But a more serious problem is that it requires more than one viewing to put the pieces together. And with that, there is a very legitimate artistic criticism, which is that the film is simply too long. There is a sense of feeling drained once it’s over. Butch’s conversations in the cab and motel room tend to drag. The film seems a bit overdone at two and a half hours. Nevertheless, “Pulp Fiction” remains the “Citizen Kane” of dark humor.

4 stars

(October 2008)

“Pulp Fiction” (1994)

Starring John Travolta as Vincent Vega ♦ Samuel L. Jackson as Jules Winnfield ♦ Tim Roth as Pumpkin (Ringo) ♦ Amanda Plummer as Honey Bunny (Yolanda) ♦ Eric Stoltz as Lance ♦ Bruce Willis as Butch Coolidge ♦ Ving Rhames as Marsellus Wallace ♦ Phil LaMarr as Marvin ♦ Maria de Medeiros as Fabienne ♦ Rosanna Arquette as Jody ♦ Peter Greene as Zed ♦ Uma Thurman as Mia Wallace ♦ Duane Whitaker as Maynard ♦ Paul Calderon as Paul ♦ Frank Whaley as Brett ♦ Burr Steers as Roger ♦ Bronagh Gallagher as Trudi ♦ Susan Griffiths as Marilyn Monroe ♦ Steve Buscemi as Buddy Holly ♦ Eric Clark as James Dean ♦ Joseph Pilato as Dean Martin ♦ Brad Parker as Jerry Lewis ♦ Angela Jones as Esmeralda Villalobos ♦ Don Blakely as Wilson’s Trainer ♦ Christopher Walken as Captain Koons ♦ Carl Allen as Dead Floyd Wilson ♦ Stephen Hibbert as The Gimp ♦ Julia Sweeney as Raquel ♦ Laura Lovelace as Waitress ♦ Michael Gilden as Phillip Morris Page ♦ Jerome Patrick Hoban as Ed Sullivan ♦ Gary Shorelle as Ricky Nelson ♦ Lorelei Leslie as Mamie van Doren ♦ Brenda Hillhouse as Butch’s Mother ♦ Chandler Lindauer as Young Butch ♦ Sy Sher as Klondike ♦ Robert Ruth as Sportscaster #1 (Coffee Shop) ♦ Rich Turner as Sportscaster #2 ♦ Venessia Valentino as Pedestrian / Bonnie Dimmick ♦ Alexis Arquette as Man #4 ♦ Linda Kaye as Shot Woman ♦ Kathy Griffin as Kathy Griffin ♦ Quentin Tarantino as Jimmie Dimmick ♦ Harvey Keitel as Winston “The Wolf” Wolfe ♦ Karen Maruyama as Gawker #1 ♦ Lawrence Bender as Long Hair Yuppy Scum ♦ Emil Sitka as Hold Hands You Lovebirds (archive footage) ♦ Dick Miller as Monster Joe ♦ Glendon Rich as Drug Dealer ♦ Ani Sava as Woman in Bathroom

Directed by: Quentin Tarantino

Written by: Quentin Tarantino

Written by: Roger Avary

Executive producer: Danny DeVito

Executive producer: Michael Shamberg

Executive producer: Stacey Sher

Co-executive producer: Richard N. Gladstein

Co-executive producer: Bob Weinstein

Co-executive producer: Harvey Weinstein

Producer: Lawrence Bender

Cinematography: Andrzej Sekula

Editing: Sally Menke

Casting: Ronnie Yeskel, Gary M. Zuckerbrod

Production design: David Wasco

Art direction: Charles Collum

Set decoration: Sandy Reynolds-Wasco

Costume design: Betsy Heimann

Makeup: Howard Berger, Robert Kurtzman, Gregory Nicotero, Audree Futterman, Iain Jones, Michelle Buhler, Bill Fletcher, Tom Bellissimo, Erin Haggerty, Ted Haines, Douglas Noe, David Smith, Wayne Toth, Christina Bartolucci, Linda Arnold, Michael Mosher

Stunts: Ken Lesco, Matthew Avila, Terry Jackson, Dennis “Danger” Madalone, Cameron, Chris Doyle, Marcia Holley, Melvin Jones, Linda Kaye, Hubie Kerns Jr., Scott McElroy