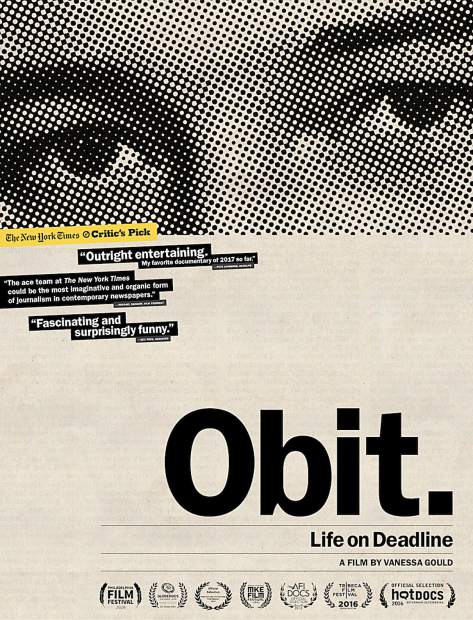

Vanessa Gould’s ‘Obit.’ is just about the last word in bourgeoisie journalism

It is said in “Obit.,” a documentary on newspaper journalists, that the New York Times has 1,700 prewritten obituaries. This is a big mistake. These articles not only dilute high-quality writing when completed, they sometimes get posted on the Internet before the person actually dies.

Questioning the process, however, isn’t part of “Obit.” (the title is given a period), one of a recent series of films about the inner workings of the New York Times, a genre that seems a reaction to the steady erosion of print news and newfound emphasis on “multimedia.”

The movie is significant because these NYT obituary positions are still on the rapidly dwindling short list of the greatest in journalism. They rank with film critic, music critic, books editor, restaurant critic, culture critic (for those papers that ever had one) and travel writer. Many of the writers in “Obit.” not coincidentally are listed as having held one or more of those positions. Many papers, even large ones, have none of those jobs now, at least not full time. “Obit.” director Vanessa Gould may or may not realize that the writers she is profiling are living history, kind of like European royalty post-WWII, maintaining a way of life that very few will experience after them.

Are these the best jobs at the New York Times? Only an insider knows for sure. These people write stories for a living, often get to choose their subjects (a younger member of the team likely at the bottom of the food chain is handed “this Argentine cardinal”), are well-paid, don’t have to rush out to fire scenes, don’t have to sit through city council meetings, don’t have to interview jocks, sometimes end up on Page 1, and work likely Monday-Friday day shifts with little interference on the vacation schedule, all for a company with perks and expense acounts. Sometimes they may face a tight deadline; usually it appears they have time to watch the Kennedy-Nixon debates.

How much do they make? Gould never asks her subjects, nor anyone who might’ve done that job recently and can now speak freely.

Downsides? Some days are slow. There’s a lot of fact-checking that can be hard to do in a short period of time. The chief gripe seems to be those megacelebs who die young, before any advance material is prepared on them. Obit writing is typically not a position of sexy scoops. Talking to grieving or cranky relatives can be difficult, although most people do want to talk about the deceased and, as is suggested early in “Obit.,” consider a New York Times obituary a badge of honor.

Never underestimate a journalist’s ability to complain. According to the NYT crew, the job only recently has shed a stigma. Bruce Weber says the obituary desk once was “kind of Siberia of the paper.” Margalit Fox says the obituary desk used to be where newsroom execs “typically sent writers whom they were trying to punish but didn’t quite have enough on to fire” and that you’d be more likely to end up there if you were a “heartbeat away from needing an obit yourself,” which sounds like potential grounds for an age-related grievance.

Obviously a 100% authorized production, “Obit.” could easily be mistaken as the work of the NYT’s promotions department. Every day, we get bright, sunny skies, countering the possible perception this is a gloomy line of work. Gould doesn’t break any ground in documentary production but does manage to annoy at times with a needlessly jittery camera. Her prime access, however, allows for impressively tight shots of journalists at work, seemingly unobtrusive. There are moments when the writers and editors appear highly conscious of cameras on themselves, such as the news meeting when Obituaries Desk Editor William McDonald explains what happened in the Kennedy-Nixon debates; other times not.

Gould alternates between showing the writers on the job, relaxed and opining on their craft at home, and the newsreel footage of the subjects they're writing about. What she needs is an argument or an emergency or a malcontent, and she doesn’t get one. Recall how the Maysles brothers tagged along on a Rolling Stones concert tour only to film (tragic) rock history at Altamont. Gould has no such spontaneity, though by constraining her crews to the offices (business and home), she doesn’t give opportunity much of a chance.

Those with experience in journalism will note that the NYT obituary team members all appear over 50. You don’t walk out of the Medill School of Journalism right into one of these posts. That didn’t happen 50 years ago, and it surely doesn’t happen now. These writers say little about their own backgrounds, but you can bet they’ve paid their dues. By the time the credits start to roll, four members of the obit team are listed as “former,” which suggests another round of buyouts took place between the filming and post-production.

“Obit.” starts with the sound of a touch-tone phone. Bruce Weber plans an obituary on William P. Wilson and is trying to reach Melody Miller; he doesn’t know if she got any of his emails, but “we would like to, uh, run an obituary, uh, about your husband.” A couple problems here; 1) we only hear Weber talking, not Miller, and 2) we’re never told how the death of Miller’s husband came to the attention of the Times in the first place. Weber notably calls Miller “Ms.,” presumably because her surname is not “Wilson,” though he probably uses “Mrs.” in a fair number of these calls.

We see the checklist in progress. Weber writes down the essentials rather than typing them. Wilson’s birth name, birthdate, education, military, etc.

We quickly begin to see the standard of verification. Some details can be checked to official documents, but much of the information will come from Ms. Miller. There is no footage of Weber examining birth and death certificates. Weber asks her about “survivors,” a most unscientific term. Has she included all the names? The actual obituary lists a daughter as a survivor. Given the timeline, she is apparently a daughter from Wilson’s first marriage. Either Miller did not have her own children (who would be considered stepchildren of Wilson), or she chose to not list them as survivors. What about when children or stepchildren have divorces; are those ex-spouses considered “survivors.” Does a person who is deemed a “partner” merit inclusion as a “survivor” if not legally married? Does Weber ask to see marriage certificates? Weber indicates the Times has guidelines but that sometimes, it just comes down to numbers. These things can get complicated.

It seems verification of death can be accepted from police or coroner or funeral home, or anyone declaring himself/herself a close relative or agent/publicist, or the person’s company or employer. Ghastly falsehoods are apparently very rare. Weber mentions writing about the author David Foster Wallace (the actual obituary cites a police report) and that to reach a relative, Weber “dialed all the Wallaces” in Illinois’ Champaign-Urbana area before reaching the deceased’s father. Did he meet the father and could Weber have been pranked? Likely no and yes (however improbable), though presumably in the course of a phone call, Weber would quickly realize if anything seems amiss. Parents would seem the most solid sources. The ex-spouses and sisters/brothers might be the more likely sources of any chicanery that occurs.

Obituaries Desk Editor William McDonald bluntly admits a more common risk of the process: “Sometimes, the original source is wrong.” Former Deputy Obituaries Editor Jack Kadden allows that people will “grossly exaggerate” the accomplishments of the deceased.

Weber makes an excellent point, wondering why anyone’s cause of death would be “embarrassing.” Yet many obituaries simply don’t include it.

Deciding who to write about isn’t very hard. There are obvious yesses and obvious nos; the ones in the middle are a matter of time and ability to speak with relatives and/or business associates. Times writer William Grimes explains that a person’s capacity for eliciting a Times obituary is based on his or her “impact” on society. Never is it discussed whether that “impact” is given a higher score if it occurs primarily in New York City rather than, say, Cleveland.

“Obit.” will take us through the William P. Wilson obituary, from checklist to Page 1 refer. Surely part of the news-meeting consideration for referencing this obituary on Page 1 has to do with the fact they are being filmed discussing it. Weber’s final product can be easily found online and unfortunately disappoints. Aware of the cameras, he was probably overthinking it. His lede is terrible, as though readers never knew that Kennedy and Nixon debated. It should say something like, “It is said JFK defeated Nixon largely because of the first debate. For that showing, the Democrat could thank William P. Wilson, the man who insisted on the single-pole podium and who applied Kennedy’s makeup. ... Mr. Wilson died on Saturday in Washington at age 86 ... ”

Oddly enough, Weber’s colleague Margalit Fox notes that “in the old days,” there was “no part of an obit more formulaic” than the lede paragraph. This time (and many others), that approach would be preferable.

Weber also curiously says twice in “Obit.” that Kennedy “acknowledged” that television made the difference in the election. Reasons for election victories and defeats are subjective and not something an individual can “acknowledge.”

Sometimes Gould’s camera seems desperate for filler. Weber mentions writing an obituary about Marshall Lytle, the bassist for Bill Haley and the Comets, and for some reason found it fascinating that Lytle’s “father was a hog butcher” and fought to keep this detail from being cut. (That obituary neatly begins with a straight news lede.) It’s also not clear why everyone seems so fascinated by Stalin’s daughter.

The early scenes of “Obit.” bounce among all the writers and introduce us to the group. No one enjoys speechmaking or reading her own text like Margalit Fox, the senior writer who asserts “readers just went nuts” about her obituary on John Fairfax and that they even claimed it’s the “most badass obit I ever read,” and she even cites two reasons why the latter comment is fascinating.

The workplaces are not individual offices but generous cubicle space adequately walled off from colleagues. Names are affixed to the cubicle in handsome lettering. Writers keep shelves of books, some of the titles seemingly having little to do with obituary writing. It’s a cozier office environment than what one sees in “All the President’s Men” or “The Post.”

Gould’s pace is annoying. While she keeps the film moving, the footage flips through all kinds of historic NYT obituary pages with just enough time to read some of the headline but not all. In another shortcoming, Gould never talks to the headline writers. Nobody addresses the importance of those headlines. How to summarize a person in just a few words. For Michael Jackson, they came up with “A Star Idolized and Haunted.” A notable element of this documentary is the film crew and NYT writers overdoing it trying to portray the writers as, contrary to likely perception, somewhat hip. We see headlines for Owsley Stanley and Helen Gurley Brown and lengthy video (by this film’s standards) of a stripper who knew Jack Ruby.

For a roughly 90-minute film, “Obit.” spends a good deal of time showing and reshowing the size of the Times archive, called a “morgue” in newspaper lingo. Jeff Roth is the guy who maintains it, and these scenes at least produce the best line of the film, by Roth: “If you misfile it, man, it’s gone.”

Roth speculates that when Ronald Reagan was shot in 1981, the Times likely didn’t have a pre-written obituary available and was probably scrambling to create one in case the president should pass away. However, a better example of scrambling would surely be JFK, or perhaps John Lennon, murdered at night in New York City at age 40, a local as well as international story.

Roth’s anecdote about the Charles Seeger photo is an implication of the monetary value of photos and documents in the NYT archive. A lot of newspapers have sold the rights to those archives; the pictures end up on eBay.

For no good reason, the camera tends to bounce at NYT news meetings. It’s not clear why eight people are needed to evaluate a photo of a man standing in a doorway. Nor does it seem like rocket science that some obituaries get one photo, others two, maybe others three, and why some get 700 words or 900 words.

Margalit Fox says she hears complaints about why the obituary section does not include more women and minorities. This allows her a chance to dispense wisdom about how the country used to look, apparently oblivious to the fact that virtually everyone quoted in this film (besides herself) is a white male.

Gould’s work is less of a documentary and more of an advertorial, but it is a relevant chapter in the sad diffusion and decline of print media. When people search for prominent obituaries online, the NYT version is typically at or near the top. These are the guardians of that placement. Thanks to this film, they know what their own headlines will say.

3 stars

(January 2018)

“Obit.” (2016)

Featuring

Bruce Weber ♦

William McDonald ♦

Margalit Fox ♦

William Grimes ♦

Jack Kadden ♦

Douglas Martin ♦

Jeff Roth ♦

Daniel Slotnik ♦

Paul Vitello ♦

Peter Keepnews ♦

Dolores Morrison ♦

Jon Pareles ♦

Earl Wilson

Directed by: Vanessa Gould

Executive producer: Pamela Tanner Boll

Executive producer: Geralyn White Dreyfous

Co-executive producer: Diana Barrett

Co-executive producer: Ann Blinkhorn

Co-executive producer: Barbara Dobkin

Co-executive producer: Nion McAvoy

Co-executive producer: Anne Milliken

Co-executive producer: Katrina vanden Heuvel

Producer: Caitlin Mae Burke

Producer: Vanessa Gould

Consulting producer and archivist: Kenn Rabin

Edited by: Kristin Bye

Cinematography: Ben Wolf

Original score: Joel Goodman

Makeup: Aina Lee