‘News’ flash: Sometimes TV

isn’t as authentic as it seems

“You totally crossed the line between what is ethical and what is garbage!”

“It’s hard not to cross it; they keep moving the little sucker, don’t they?”

Where’s the love in “Broadcast News”?

Not every movie needs a romance. A story of attractive TV faces is one that does. But the characters in “Broadcast News” don’t connect and don’t even use each other for sex. Rather, they use each other for keeping score on the career ladder.

It might be possible to get excited about workaholics and their craft, particularly when the actors are as gifted as these, but writer-director James L. Brooks’ story is steadfastly middle ground. The memorable films on TV news, such as “Network” and “Anchorman,” grab the more dubious elements and yank them over the top, whether it’s a loopy anchor saying “I’m as mad as hell” or the nightly news team in ’70s three-piece suits and combovers. The best “Broadcast” can do is wry sarcasm on the petty office politics, though many of the lines are remarkably witty.

“News” is best regarded as a sum-of-the-parts success. A limited number of scenes and themes are profoundly effective. The casting is across-the-board perfection. That it doesn't all culminate in a perfect conclusion — or anywhere close — is disappointing, but not a deal-breaker.

The film’s best moment is when Tom Grunick is suddenly thrust into a live breaking-news update on a Libyan incident. This is effective. Tom’s prank of ignoring Jane just before air-time — an unexpected moment revealing his coolness under pressure — is golden. However, because an earlier report already depicted Tom as outperforming in the category of producing compelling television, his success is not as much of a twist as it should be, and certainly reaction to Aaron’s Nicaragua report coupled with his grumbling about lack of credit ensures no viewer will be nearly as devastated by his Libya snub as Jane is.

Jane’s party discussion with Jennifer (Lois Chiles) as to who gets to date Tom is delicious; Jane barely betraying her emotions to a refreshingly nonchalant rival who is oblivious to them. Jennifer seems a perfect match for Tom. But he senses something on the intellectual level of Jane, and somehow Jennifer never has a chance. In a clever follow-up soundbite revealing Jane’s instincts, Jane will bluntly suggest to other bosses that Jennifer be sent to Alaska. In a filmmaking lapse, Jennifer, a character classically discarded when no longer needed, is nowhere to be found during the layoff announcements. (Chiles coincidentally also played the third wheel in a dating universe of three in “The Way We were.”)

And then there is the station boss, Ernie Merriman (wonderfully understated by Robert Prosky), jaded by the work and directives he must oversee each day, who seems to be a pro-Aaron kind of guy but can’t fully hide his honest professional assessment of Aaron’s skills when agreeing to give him a chance as weekend anchor.

Authenticity can be an appealing film subject. Robert Redford is famous for exploring it, particularly in his landmark work, “The Candidate.” Television is widely viewed by the movies as phony. Consider just about any movie with a public disturbance (“Die Hard”? “John Q”?) where the blow-dried reporter rudely barges into a sensitive moment with the tired protagonists, asking questions in jaw-droppingly poor taste.

“Broadcast News” is not actually above this. The difference is, its characters know it. And so we are handed people who know the drill from early age and, by the end, have gained little more than new assignments.

Brooks takes a risk in opening with childhood depictions of characters we haven’t met yet. There is something memorable in how these children behave, but is it necessary? It doesn’t take long after our introductions to Aaron and Jane to figure out how they must’ve been as students.

Tom’s childhood portrayal — the first scene — is the worst, though there is nothing wrong with the acting by young Kimber Shoop who, for whatever reason, has never been credited with another feature film. An elementary schoolkid is distressed because women like him too much. “What are you supposed to do when people keep commenting on your looks? I don’t even know what they mean, ‘beat ’em off with a stick.’ ... What can you do with yourself if all you can do is look good?”

Not only is it reaching to portray a boy having these concerns, it preempts what story arc exists by robbing the future Tom of a gradual, important realization. He should be flaunting his looks as a boy, enjoying the attention, only to realize later in life the value of career and respect from colleagues and that his appearance won’t give him that.

If there is a realization to be made it is by Aaron, who ultimately concludes he is not right for this network affiliate or perhaps even this business. Aaron does seem like lawyer material, perhaps miscast from the beginning. His problems with TV stardom obviously are occurring long before Tom enters his world. He pulls off a risky report embedded with the Nicaraguan Contras (which at the time probably didn’t seem like a chancy theme to Brooks but adds to the film’s dated feel today) but gets virtually none of the acclaim, which somehow goes to his producer — Jane, who is so uptight about ethics she interrupts a soldier putting on his boots. For such a bright guy, Aaron was born yesterday. It takes him a very long time to “get it” — that others with lesser academic credentials are deemed more valuable television commodities than he is, and that it’s not really anyone’s fault, it’s how the system works.

It should fall upon Holly Hunter’s Jane to deliver the love triangle. The pieces are there for effective drama — she can choose the phony success, or the authentic, underappreciated performer. But she is never given a chance. Something always prevents Tom from breaching the final social barrier with her, and as for Aaron, they’re mysteriously good buddies and never anything more (something else it takes Aaron a long time to figure out). Every time Jane and Aaron are together, the film stalls stupendously. The audience is not interested in seeing them hook up. They are not equals in terms of skill level but only in their disdain for the profession they’ve chosen.

According to the book Inside Oscar, Brooks “had Debra Winger in mind” for Jane. But Winger was pregnant, and, at the end of a six-month search for a replacement, Brooks finally discovered Hunter, a “New York stage actress” with a few film credits.

Does Jane really disown the gloss of television as she claims? Her appearance is exquisite for someone who revels at being in the trenches. One wonders why she is not an on-camera personality. Yes, she is remarkably good at producing, and putting a story together, but as everyone in the film acknowledges, the big money and success go to the people who look good delivering a story. Surely such a go-getter would consider this route herself. But maybe there is a good reason ... that Jane, despite all of her laudable hard work, doesn’t quite “get it.” People don’t want news of policy positions all the time; they want to see things like falling dominoes in the same manner they want a sports section included with the op-eds. While Jane leaves hints that open up her character to skepticism, there is none for Hunter. She owns many of the scenes. Hers is an edgy beauty, a remarkably disarming presence, almost knee-buckling, like a pitcher with a great curveball. You do not want to try to run over her if she is in your way; you are going to go around to get past her at all.

Perhaps suggesting that Hunter owns many scenes is selling William Hurt, like his character, short. Hurt, a regular at the Oscars in the mid- to late 1980s, makes the most of his limitations of any of the three major characters. He seizes on a genius, subtle little thread in James Brooks’ script of asking questions. Notice that Tom, unlike his colleagues/rivals, is very interested in improvement in feedback. He wants to know how to do it better. Hurt succeeds in making this appear as though Tom is grasping, when in fact he is outperforming. Hurt has a way of appearing dumbfounded when people are trying to tell him rather straightforward things. Yet he not only makes the film’s undeniably best scene during the Libya report; he draws a beautiful contrast between his sage anchoring advice for Aaron and his utter bungling of Aaron’s cagey pop quiz.

A few scenes are much less impressive. Primarily, Aaron getting his chance as weekend anchor and flubbing. That scene feels amateurish, sitcom-like (a Brooks specialty) and well below the extremely lofty aspirations of this film. (Admittedly, a couple parts of it are hilarious, the staffer banging the map and Brooks’ line about “I wish I were one of them.”)

Another is when the high-octane gopher played by Joan Cusack sprints a tape to the newsroom on deadline ... and makes it by 1 second. On the one hand, this is a great depiction of how TV producers often meet tight deadlines with creative ideas. On the other hand, Cusack encountering the perils of filing cabinets and drinking fountains comes across as cartoonish. (Nevertheless, that scene was the movie’s “most appreciated” among TV pros interviewed in 1987 by Yardena Arar of the L.A. Daily News.)

If this film really believed in any romance potential, the critical breakup near the end — when Jane abandons the vacation flight — might pack a little punch. It packs none and borders on absurdity.

Consider the options Brooks might have pondered while developing this story ... perhaps a reversal of the film’s sexual reticence. The characters sleep around and score whenever possible. Somewhere beneath the frat-caliber fun there is a growing sense of underestimating each other and their profession, and a realization they’re not taking themselves, or each other, seriously enough. That would be a stark departure from Brooks’ highly conservative Washington bureau perception, where getting a simple date is an ordeal, but at least allow the characters to actually have fun when not at work. It’s not unreasonable to infer that Brooks views the TV news business lower than any of his characters, as a complete zero, artificial and useless, an unsustainable business model. If it’s going to be that way, can’t it at least be funny?

Jane is evidently based on Susan Zirinsky, a CBS producer for Dan Rather’s evening newscasts in the 1980s. According to Arar’s article, Zirinsky served as a technical adviser and “bears a striking physical resemblance” to Hunter. Les Krepman, an assignment editor for NBC at the time, told Arar, “Holly Hunter’s portrayal of Susan Zirinsky is right on the money.”

How much of a breach was Tom’s editing of the tear in his rape report? It would be an embarrassment, but only of the type covered by insiders and media critics. The public would not care, and many likely would not even understand why it is considered a breach. Tom might get some kind of internal probation (more likely, a warning not to do it again), but otherwise his career should proceed as planned.

“Broadcast News” only wants a brief flirtation with satire, not nearly the type of complete slapstick in, say, “Anchorman.” It doesn’t try to be funny, only occasionally wry, because it feels like Jane won’t let it be any other way. The scene of Aaron’s massive perspiration is over the top for this film. It’s not particularly funny because this is beyond what Aaron’s sense of humor is capable of handling and it oozes sympathy for him. But some found it wittier. Vincent Canby in the New York Times in December 1987 called the film “very funny, occasionally satiric.”

Brooks underplays one potentially good scene when the network chief suggests the star anchor, played by Jack Nicholson, could ease the layoff situation by taking a pay cut. Jack’s cold stare and the boss’ panicky backpedaling makes a humorous, and effective, point that the on-air stars tend to control TV decisions as much as the executives. But this scene is curiously shot from a distance, and we don’t get a tight close-up of Jack’s face that the moment calls out for. (Brooks also takes a risk here in casting a giant like Nicholson to bring stature to that position while not billing him as a star and undermining the troika. This risk pays off.)

While the opening childhood scenes are superfluous, the ending is flat-out counterproductive, raising unnecessary skepticism of the characters. Tom has finally accepted his fate, that he somehow can’t connect with a woman of substance no matter how much he wants to and thus must accept a glossy model type. Jane’s finally got a man in her life, offscreen.

The film struggles with locations and job descriptions, especially at the beginning when a sense of who’s doing what and where is needed most. Once the childhood depictions are over, we see Jane jogging briskly and, as would be expected, grabbing five daily newspapers from a row of six vending machines. Curiously, two of the machines say “Omaha” and “Nebraska.” Then we suddenly see Jane in her in a hotel room, talking on the phone with Aaron, who is in another hotel room; they must be on location to confront a subject on a bus, but Jane is shown bursting into tears. After reviewing the tape of the bus man, Jane is shown giving her speech, which appears to be in Washington, which apparently is where she lives. The descriptions of her network’s arrangement between bureau, local and network broadcasts are, to be kind, not always clear. Tom tells Jane he has been hired by “your network, Washington bureau.”

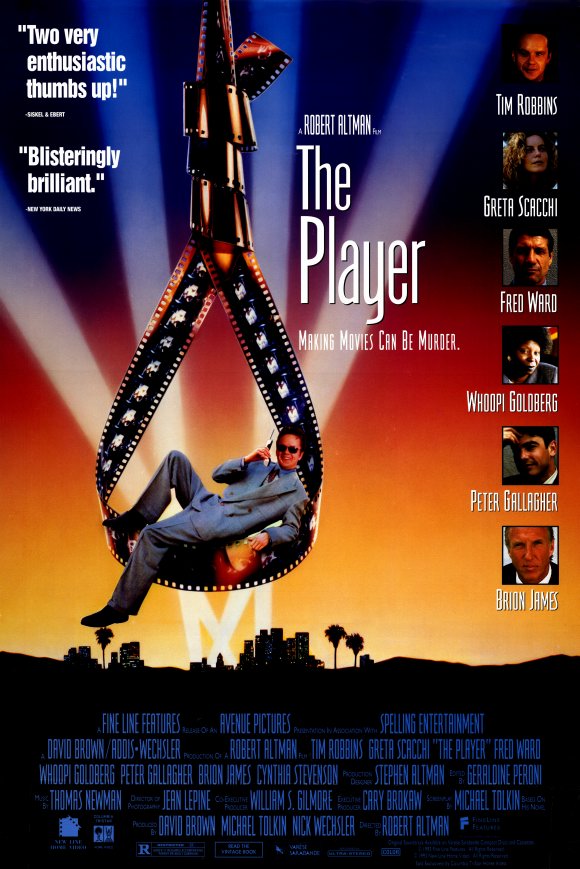

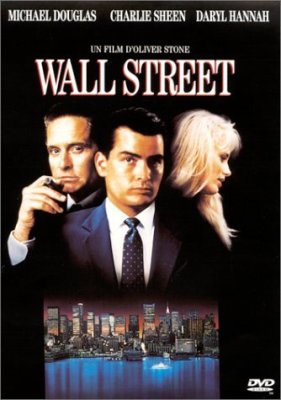

Brooks’ credentials for this film were impeccable. A former writer for CBS News, creator of “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” and “Lou Grant” and several others, writer-director of “Terms of Endearment” all on the resume. “Broadcast News” came about with very high expectations. Oliver Stone has noted in interviews that 20th Century Fox decided to push “Broadcast News” for serious Oscar consideration ahead of his own film that year, “Wall Street.” The effort was successful, as “Broadcast News” delivered seven Oscar nominations, including for all three main actors and best picture.

But it won none of those. Oscars are difficult for contemporary dramas without period costumes and gee-whiz special effects and imposing scores. They are even tougher for films that hint at being more comedy than drama. “News” was shut out for reasons apparent when checking any random cable TV guide. “Wall Street” and “Moonstruck,” less celebrated films that did win Oscars that year, play far more regularly. So does “The Untouchables,” whose Sean Connery bested Albert Brooks for a supporting actor Oscar. Hurt lost to Michael Douglas, and Hunter lost to Cher. James L. Brooks was denied a directing nomination; his film lost to Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Last Emperor.”

“Broadcast News” likely received slightly better reviews than it deserved because it views TV news the same way many print journalists do. It fulfills their vision and, particularly in the form of Aaron, vindicates their belief that in all of TV’s glitz, on some level, real journalism is getting screwed.

It would be fascinating to know what real TV anchors and reporters think of the film. Many are the real deal; a few are phonies as in any other line of work. The guess is that they would look more fondly upon Jane and view the male stars with disdain.

Who is right about television, Tom or Jane? Tom isn’t capable of making his own argument, so we’ll make it for him. There is definitely a value to television. Delivering it requires attractive, comfortable faces just as delivering print news requires black ink on white paper. The people in “Broadcast News” can’t stand that.

2.5 stars

(June 2009)

“Broadcast News” (1987)

Starring William Hurt as Tom Grunick ♦ Albert Brooks as Aaron Altman ♦ Holly Hunter as Jane Craig ♦ Robert Prosky as Ernie Merriman ♦ Lois Chiles as Jennifer Mack ♦ Joan Cusak as Blair Litton ♦ Peter Hackes as Paul Moore ♦ Christian Clemenson as Bobby ♦ Jack Nicholson as Bill Rorich ♦ Robert Katims as Martin Klein ♦ Ed Wheeler as George Wein ♦ Stephen Mendillo as Gerald Grunick ♦ Kimber Shoop as Young Tom ♦ Dwayne Markee as Young Aaron ♦ Gennie James as Young Jane ♦ Leo Burmester as Jane’s Dad ♦ Amy Brooks as Elli Merriman ♦ Jane Welch as Anne Merriman ♦ Jonathan Benya as Clifford Altman ♦ Frank Doubleday as Mercenary ♦ Sally Knight as Lila ♦ Manny Alvarez as Spanish Cameraman ♦ Luis Valderrama as Guerilla Leader ♦ Francisco García as Guerilla Soldier ♦ Richard Thomsen as General McGuire ♦ Nathan Benchley as Commander ♦ Marita Geraghty as Date-Rape Woman ♦ Nicholas D. Blanchet as Weekend News Producer ♦ Maura Moynihan as Makeup Woman ♦ Chuck Lippman as Floor Manager ♦ Nannette Rickert as Paul’s Secretary ♦ Tim White as Edward Towne ♦ Peggy Pridemore as Tom’s Soundwoman ♦ Emily Crowley as Emily ♦ Gerald Ender as Newsroom Worker ♦ David Long as Donny ♦ Josh Billings as Chyron Operator ♦ Glenn Faigen as Technical Director ♦ Robert Grevemberg Jr. as Technical Director ♦ Richard Pehle as Control Room Director ♦ James V. Franco as Weekend News Director ♦ Jimmy Mel Green as Assistant Director ♦ Raoul N. Rizik as Assistant Director ♦ Mike Skehan as Technician ♦ Franklyn L. Bullard as Audio Visual Engineer ♦ Glen Roven as News Theme Writer ♦ Marc Shaiman as News Theme Writer ♦ Alex Mathews as Lecture Host ♦ Steve Smith as Aaron’s Cameraman ♦ Martha L. Smith as Aaron’s Soundwoman ♦ Cynthia B. Hayes as Mother in Hall ♦ Dean Nitz as Young Tough ♦ Phil Ugel as Young Tough ♦ Lance Wain as Young Tough ♦ Susan Marie Feldman as Ellen ♦ Jean Bourne Carinci as Tom’s Female Colleague ♦ M. Fekade-Salassie as Cab Driver ♦ Jerry Gough as Uniformed Cop ♦ Robert Rasch as Defense Dept. Spokesman ♦ Robert Walsh as NATO Spokesman ♦ John Cusak as Angry Messenger ♦ John Badila as Guest at Ball ♦ Heather Ehlers as Guest at Ball ♦ Arlene M. Dillon as Guest at Ball ♦ Sam Samuels as Guest at Ball ♦ Rochelle Deering as Woman at Speech ♦ Albert Murphy Sr. as Man in Airport ♦ Eleanore C. Kopecky as Woman in Airport ♦ Jeffrey Alan Thomas as Airport Cabbie ♦ Brad Baker as Businessman ♦ Denise King as Copy Runner ♦ Nancy Kirk as Airport traveler

Directed by: James L. Brooks

Written by: James L. Brooks

Co-producer: Penney Finkelman Cox

Executive producer: Polly Platt

Producer: James L. Brooks

Associate producer: Kristi Zea

Associate producer: Susan Zirinsky

Original music: Bill Conti

Cinematography: Michael Ballhaus

Editing: Richard Marks

Casting: Ellen Chenoweth

Costume design: Molly Maginnis

Production design: Charles Rosen

Set decoration: Jane Bogart

Unit production manager: David V. Lester

Makeup and hair: Colleen Callahan, Carl Fullerton, Craig Lyman

Stunts: Jery Hewitt