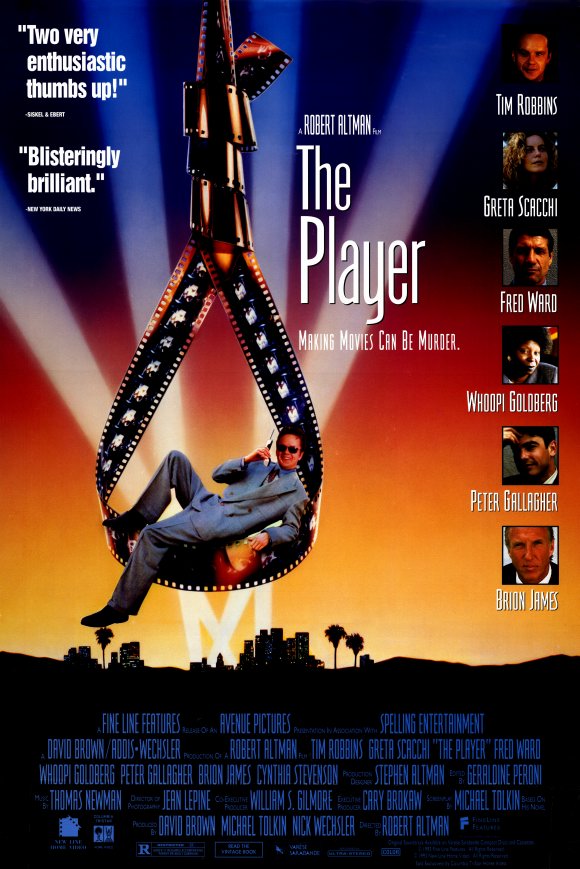

Robert Altman’s ‘The Player’

manages to turn Hollywood

into a sympathetic character

Griffin Mill has a great office. How he got there is of no concern.

What is of great interest is how the people pitching — or reading — movie scripts might get there. What does it take to get Mill to hear your idea, or to hire you? “The Player,” a 1992 Hollywood satire by Michael Tolkin and Robert Altman, is not concerned about such low-level machinations. These are the big fish. This is satire, but for the 1%. Not 1% of the public ... but 1% of Hollywood.

Altman fronted the project, written by Tolkin and based on Tolkin’s novel. The movie was widely considered Altman’s statement. Incredibly, he has managed to be too hard on Hollywood. “The Player” actually was helmed by Sidney Lumet for a few weeks before his vision was deemed too expensive. Altman calls the film “an essay on morality.” It’s really an antihero story. Griffin Mill doesn’t have guns, but something far more powerful — a Hollywood parking space.

Tim Robbins’ performance as Mill is a tour de force, because Mill plays offense in life. It doesn’t take long to realize that much of what Mill says cannot be believed. The rest of what he says is staggeringly perceptive. For maximum impact, Mill must succeed in show business in the most offensive way possible. Break promises, break laws, lie, deceive. We’re torn between alarm at what he is doing and admiration for how he does it. Tolkin and Altman cleverly give Mill a tiny amount of justification for his deeds, so that we cannot totally hate him.

Griffin Mill is not the first character to aggrieve society and get away with it. There was the cunning Eve Harrington in “All About Eve,” there was Michael Corleone. A 2012 film, “Arbitrage,” is the hedge fund equivalent of “The Player,” featuring Richard Gere as a shady executive who thrives on heat. The worse it gets for him, the better he does. All of those films include an important qualifier: The world that these characters operate in is virtually as dubious as they are, so they are given a grudging moral endorsement. On the same day Griffin Mill learns his replacement has been hired, he receives a death threat. This is what’s called clearance, for a self-defense case.

“The Player” is best regarded as a sum-of-the-parts success. The whole is watered down by a lifeless romance, a thin noir and celebrity O.D. The signature sequence is the opening, an uncut marvel lasting about 8 minutes (Altman says in DVD commentary it took about 15 takes) of busy people coming and going at a studio campus. Anytime characters are sitting around discussing movies, the scenes are priceless. “Political doesn’t scare me. Radical political scares me. Political political scares me.” This is the epitome of a tough crowd.

How does one get a script read by Hollywood? Altman utterly dismisses the notion of dreams and breaks in “The Player.” That’s the prequel. Here, every character is credentialed, a mature industry pro. How some are able to get into Mill’s office — or just into the studio campus restaurant — is left unexplained. Presumably Mill or his bosses have worked with them previously. In the extended opening scene, Mill listens to 3 proposals within roughly 8 minutes. “We hear about 50,000 stories a year,” Griffin reveals near the end of the film, explaining that only about 12 of those stories will be chosen, and this is one moment in which he is a sympathetic character.

Allowing for the notion that someone in Mill’s position probably gets pitches everywhere he goes, even on holidays, that comes out to about 137 proposals a day, likely more than he and his staff can reasonably handle. No doubt the vast majority went straight to a mail room wastebasket. There’s an implication from a Tom Wolfe reference, obviously an accurate one, that books are the springboard to many film projects; let the publishing houses sort through this stuff first. The next best way to get heard is to have a previous credit, so if you’re pitching your first script, consider Powerball a more viable option.

There is film as business, and film as art. Ideally, they would coexist. “The Player” is about the tension between the two. Every year there will be about 200 hundred feature films released to American theaters. A massive majority will be mediocre. Others will find devoted fans but not a robust box office. Collectively there will be some kind of profit, and every film will provide some level of work. Altman acknowledges the differences between himself and the studios/distributors in the DVD director’s commentary; “we just basically aren’t in the same business.” He complains in this commentary that Hollywood only cares about “teenagers, and preteenagers,” and seeks the “lowest common denominator” for a market. For the most elite and skilled executives, it seems that it’s those handful of films at both ends of the spectrum that will make or break careers, sort of like playing poker for hours and realizing the night came down to a couple of hands.

But once you get your foot in the Hollywood door, the film implies, you’re taken care of on some level. In an interview at the time, Altman singles out Hollywood salaries as a source of his irritation. The implicit message of “The Player” is that Hollywood is something like the oil market: obscenely profitable on a per-person basis. Studios surely lose money on certain initiatives. Overall, it’s an oligopoly. It’s got the market cornered on an extremely prized commodity — movie stars — and is flooded with unsolicited supply of actors, writers, scripts, producers, ideas. It can be inferred from “The Player” that the real goal of people up to and even slightly above Mill’s level is not to excel in Hollywood, but to get your foot in the door. This is very apropos to vaunted institutions such as Harvard, Goldman Sachs, Google. Once there, you can do well without really doing anything special. “The Player,” to indulge in understatement, paints moviemaking as a mature, tapped-out business that serves its employees before customers, the only real drama happening offscreen. This is not the place you go for a risk-taking startup, but to cross over to the safe side of an old-money moat, a fountain of dollars and status.

“The Player” begins where “Broadcast News” ends. Both outfits are well-familiar with media boom-bust cycles; in “The Player” the upheaval is happening at the beginning, and the movie proceeds with jobs on the line. The films are in agreement that the downsizing is unfair, the decisions on personnel perhaps reflect shreds of truth but are anything but judicious.

“The Player” is certainly a coming-of-age story, even if Mill is older than perhaps a typical coming-of-age protagonist. Robbins was 33 when “The Player” premiered, his age perfect for this character. Robbins can pass for much younger, but as Mill, he conducts himself with maturity beyond his years. He is in the big leagues but not entirely secure, either about to get promoted to starter, or sent down to the minors.

Early on, we’re shown 2 characters who might rival Mill: Reg Goldman, a young airhead whose banker father has his hands on the studio’s purse strings, and Larry Levy, a “comer” from rival Fox who appears to be Mill’s peer and is brought aboard simply for the sake of change. In singling out the villain, Altman entertains no drama. Mill scoffs at the presence of Goldman and quickly identifies Levy as the real threat.

The threats Mill receives are a macguffin. It is a clever way of giving Mill the motivation to attack David Kahane. There are other ways Tolkin and Altman could’ve gotten there, but anonymous postcards lend a delicious whodunit quality. The problem is that just as this element is intensifying, it is forgotten by a script that curiously ceases to care about it, rekindled at the end to imply Mill hasn’t completely gotten away with his misdeeds, though he has. His secretary was well aware of the postcards. Surely in such a gossip town, Mill’s legal jeopardy would’ve been the subject of whispers and innuendo. Mill would have no need to cut a deal with his harasser. This, according to Tolkin, is probably the greatest slight to his book, but more on that later.

Mill notably does not ask the studio’s capable security chief, Walter Stuckel (a legacy hire, as he mentions in the opening uncut scene his father’s history as a grip while paying tribute to 2 other legends of the long cut, “Rope” and “Touch of Evil”), to handle the threats. Mill’s secretary wonders why. Mill says doing so would make him an “object of ridicule” just while his job is on the line, an argument that proves flimsy. As a detective, Mill is downright incompetent. His basis for identifying Kahane, Altman admits in DVD commentary, is “pretty illogical.” Misunderstandings give him reasonable grounds to consider Kahane the suspect, but Kahane says enough to make clear he’s not the guy, comments lost on Mill. There are no realistic suspects, not even David Kahane. And why would the harasser, who is demanding nothing, after placing a snake in Mill’s car and seemingly indecisive as to whether he truly wants to harm Mill, fade away as the pressure on Mill heats up? Altman gives us no specifics on who the accuser might be, the implication being, treatment of writers is so egregiously dismissive, it might as well be anyone. One blogger says the caller to Mill at the end of the film is the voice of Phil, David Kahane’s friend who eulogizes him at his funeral.

Mill’s motivation for confronting his tormentor is specious. Presumably, based on his conversation with Kahane, he is hoping to calm down the postcard-sender and assure himself that this individual is not a threat. At no point is it implied that Mill wants the writer arrested. Making contact with this person, for the purposes of feigning interest in his ideas, seems useless at best and foolhardy at worst. This is evidenced by Altman’s uncertain handling of the goofy Mill-Kahane meeting in the karaoke restaurant, in which Griffin seems to have no idea what he is doing.

This plot is undercooked by Altman and Tolkin. It just doesn’t fit together. A lot of movies successfully pin a protagonist into a threatening situation in which he can’t summon police, such as Michael Douglas in “Fatal Attraction” (a film referenced dubiously in “The Player”). Here, Mill should have no concerns. Writers here are cattle. Some are nutty. The fact he made such a bizarre impression should be worn as a badge of honor. Tell Stuckel, then forget it and concentrate on Levy.

Kahane is clearly a buffoon who doesn’t deserve to be optioned. Mill notes that Kahane is “unproduced.” Why Kahane would even remember one jerk out of obviously many who have turned him down, who knows. Here he’s been given that rarest of Hollywood assets — an opening — only to completely bungle it. This sequence, in a strange Japanese karaoke restaurant, is borderline unbelievable. Instead of vigorously promoting his script, he chides Mill for forgetting it. He correctly observes that Mill is a phony and lying … but who cares? This is Hollywood. Mill is offering a 2nd chance that Kahane surely doesn’t deserve, thanks to a fortunate misunderstanding. Kahane is the anti-Mill, principled and clueless.

If only the writers were more like Mill, they’d have a better chance of getting ahead. A much savvier duo introduces Mill to the “Habeas Corpus” script. But this sequence is clumsy if not amateurish. Mill is supposed to meet his secret harasser at a restaurant but instead bumps into a gruff Roddy McDowall, then a pair of writers, Tom Oakley and Andy Civella, who awkwardly introduce him to Andie MacDowell, who can’t wait to exit. Mill excuses himself from the writers to wait in the restaurant, alone, for his tormentor, only to have Civella resurface at his table and insist Mill hear their pitch.

If we skipped Andie MacDowell, we could simply have Mill seated alone at the restaurant and surprised by savvy writers sensing a sudden moment of opportunity. Mill initially thinks these are his harassers, then realizes they just want to sell a script, and is relieved to be distracted by typical business minutiae.

There’s a beautiful potential for message here. Kahane is the idiot who thinks Hollywood success is determined by scheduling meetings and making official proposals. Civella and Oakley by contrast are the ambitious pros who realize success is realized not just through hard work, but breaks and moments. Mill wandering around the same restaurant they’re at is the most golden of opportunities. The problem is that Altman doesn’t even make Civella and Oakley that savvy; it takes them time to figure out what they should be doing. A little bit lucky and a little bit good, but not an exceptional amount of either. At least Dean Stockwell, as Civella, uncorks the funniest line of the film during their pitch, telling Mill, “You’re good,” and affirming to Oakley, “See I told you, he’s good.”

One surely must wonder, why in the world would a studio protect Mill from his legal jeopardy? Companies routinely defend executives in business-related cases. This one sort of qualifies. Anyone with a passing interest in Hollywood knows that this is what studios did, or do, for their biggest stars, but that seems confined to DUI and domestic scrapes and nervous breakdowns. The notion that Mill might be a very dangerous individual bothers no one. This is Altman’s vision of an industry out of control, that it will overwhelm law enforcement to defend not just wayward, crackpot entertainers, but exploitation and desecration of art.

Altman not only mishandles the macguffin, he overdoses on movie stars. In a dubious decision, he admits calling as many as he could for cameo purposes. This backfires, turning “The Player” into as much of a fawning tribute as a sizzling skewering. There was initial risk in casting about a dozen well-known faces as characters and surrounding them with real-life stars playing themselves. That somehow proves workable, until it becomes clear, the “himself” and “herself” characters have nothing to do with anything. The brushes with Marlee Matlin, Anjelica Huston and John Cusack feel authentic, but in several unfortunate scenes including Burt Reynolds, Andie MacDowell and a charity banquet, “The Player” feels less like a cutting-edge insider and more like an autograph seeker.

The total amount of stars enlisted here has nothing to do with the movie but everything to do with inside score-settling; this is Altman’s way of telling the studio system, “Look who’s on my side.”

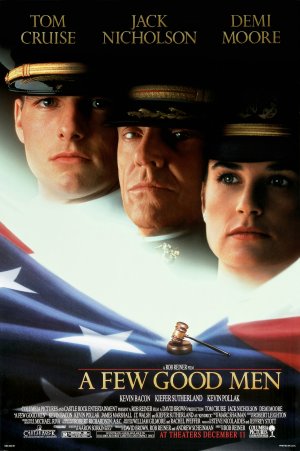

If one is impressed by this cameo ledger — and it is a fairly famous list — consider who is not in the credits. Jack. Clint. Liz. Redford. Streep. Beatty. Brando. Pacino. Hepburn. Cruise. Fonda. De Niro. Hackman. Dunaway. Stallone. Harrison Ford. Michelle Pfeiffer. Demi Moore. Dustin Hoffman. Sigourney Weaver. Michael Douglas. Woody Allen. Jodie Foster. Tom Hanks. Glenn Close. William Hurt. Diane Keaton. Paul Newman. Sally Field. Denzel Washington. Ben Kingsley. Bob Hope. Holly Hunter. Mel Gibson. Kathy Bates. Charlie Sheen. Martin Sheen. Melanie Griffith. Jessica Lange. Arnold Schwarzenegger. Julie Christie. George C. Scott. Richard Dreyfuss. Morgan Freeman. Shelley Duvall. Jon Voight. Robin Williams. Keith Carradine. Ned Beatty. Sissy Spacek. Peter O’Toole. Michael Caine. Robert Duvall. John Travolta. James Woods. James Caan. And at least 3 mentioned in the film, Meg Ryan and Goldie Hawn and Kevin Costner. Many of the credited cameos are actors from Altman’s films of the 1970s but some of his regulars, including Keith Carradine, Shelley Duvall, Geraldine Chaplin, aren’t a part of “The Player.”

Altman told a newspaper, “I expected a lot of ducking,” but resistance from celebs was deemed “minimal.”

“The reason all these folks showed up is that they wanted to hold their hand up and say, ‘I want to be counted, I want to be part of this.’ They sensed that this was a protest,” Altman contended.

One reason stars might be reluctant for such a project is because, despite taking the time to show up, they might actually get cut, as happened to Patrick Swayze, Jeff Daniels, Martha Plimpton, Tim Curry and Lori Singer. “There went a lot of wonderful people,” Altman said.

Altman says in DVD director’s commentary that he summoned the actual stars to “pump the, the reality … of the whole project.” He says in this commentary, “Everybody responded to it; some people couldn’t do it … most of ’em did.”

Unfortunately, he admits what is readily apparent, “I never gave anybody a line,” because he doesn’t think he can tell them what to say when they are appearing as themselves. He wanted them there, and had nothing for them to do, a serious problem for any movie.

Taking this approach costs Altman a chance to create a greater edge in the already engaging pitch scenes. Altman says he let the actors invent their own dialogue. It is unclear if the proposals by Buck Henry (“The Graduate, Part II”), Alan Rudolph and Joan Tewkesbury, often described as a cross between 2 well-known films (for example, “It’s ‘Out of Africa’ meets ‘Pretty Woman’”), are meant to be quality ideas that never get a chance, or drivel that Mill has to slosh through daily.

Altman’s effort here prompts a question — is it impossible to get too many roles in Hollywood? How many movie stars at any given moment are actually eager for more jobs? Perhaps more than you’d think. Maybe there’s a far more important reason than loyalty for taking up Altman’s offer: They need the work. It puts them in another film, keeps them in the orbit. And it’s minimal time and effort. You can’t have too many credits.

“The Player” would pack a greater punch if Mill were given a more colorful opponent than just the system. Whoopi Goldberg, who flourishes as the easygoing skeptical Detective Avery, could be such a character, but she doesn’t get enough scenes for such an assignment and doesn’t take the case seriously enough.

Peter Gallagher’s Levy never quite seems like he will supplant Mill; he is curiously portrayed as being a hard worker with (albeit discouraging) ideas and not so much a cunning saboteur who orchestrated a dubious job switch. (In one of the film’s best lines, Levy indicates that in Hollywood, even AA meetings are phony; he goes because “that’s where all the deals are being made these days.”) But ultimately Levy and Levison are nothing more than patsies; Sydney Pollack’s credible Dick Mellon seems too much of a clash with Levison’s role as to who the viewer identifies as running the show, a Barzini-Tattaglia problem.

There’s an effective contrast between the studio’s 2 no-nonsense professionals. One of them is Dina Merrill’s Celia, the senior secretary of Joel Levison. The other is Cynthia Stevenson’s idealistic, ceiling-sensitive Bonnie Sherow. Celia gets it, and that’s why she is still here at her age. Bonnie doesn’t get it; that’s why she’s sent packing.

Sherow is perhaps the hero of the film, in the manner of Jake Gittes. She fights to do the right thing, and ultimately realizes in horror the truth about what’s going on. Altman gives her a disdain for her environment and its parties (“Oh God, movie stars and power players”), and he effectively uses her to fuel the satire as the lone topless woman in the film, at a Hollywood executive home, because “it’s a satire on everything we do,” the pool, “that’s a Hollywood thing.”

Randall Batinkoff’s Reg Goldman is highly effective in very limited time; a numbskull given entree to the creative process because of the dollars of his family. Similarly, Gina Gershon, as Whitney Gersh, an up-and-comer in the story-editing field, makes disturbingly clear she roots for the winning team.

Somewhat iffy is Fred Ward’s Walter Stuckel. He looks the part 100% and plays it with a compact vigor. But he’s never given a side and thus becomes, like all other supporting characters, a patsy. He insists Mill not lie to him, but it’s unclear what kind of outcome he wants in this case; justice apparently a secondary concern.

Another character actor is the collection of movie posters employed by Altman. About 8 of them are prominently shown. Famous titles include “Casablanca,” “Notorious” and “Laura,” which presumably are supposed to represent a high standard (these are minty white and appear to possibly be reprints; it’s unclear if studios would hang 5-digit artwork on their office walls). But the posters getting the most screen time and presence are the half sheets of B-movies no one has heard of but whose titles overtly convey Mill’s present and future: “Prison Break” and “Murder in the Big House.” (There is also a German re-release of Marlene Dietrich’s “Blue Angel,” which might be a reference to Greta Scacchi or might be a favorite of Altman.)

“The Player” fizzles in the romance department, promising far more than it delivers. Mill’s early scenes with Bonnie are sterile. Initially Mill’s dalliance with his newfound lover is edgy, until it becomes clear, they’re boring together. Altman, bogged down by repetition in this film, inexplicably sends Mill to her boring home 4 times. What should be a powerfully edgy ending is sapped by their ridiculous mud-caked spa excursion. This unfortunately gives “The Player” something in common with “Wall Street,” a film it references, as Scacchi proves as uninteresting of a pursuit as Daryl Hannah’s Darien. Of all the people in Mill’s stratosphere that he could court, she is most insignificant.

She does, however, possess one important quality that appeals to Mill: She’s not in Hollywood, and she doesn’t care. Mill realizes June is his soulmate when she happens to tell him, “I think knowing that you’ve committed a crime is suffering enough,” a rationalization that sounds so Hollywood.

Kahane’s funeral is one of several tedious, over-the-top sequences. At least 3 times, viewers must hear the pitch for “Habeas Corpus,” even though it seems overdone the first time. The banquet for the L.A. County motion picture museum exists just to show the celebs and allow Mill to lie again. The party at Dick Mellon’s suggests something important will happen that never does.

However phony the environment, Hollywood, evidenced by Altman’s cozy cinematography, is an extremely appealing workplace. The studio is a completely insulated campus where sports cars come and go. (Not every car in the lot is expensive.) The offices and restaurant tables represent healthy brainstorming sessions: Listen to ideas, opine on them, read your own press clippings, mingle among celebrities, take advantage of the generous expense account.

If you work here, you look good. Business suits fit loosely on the men and women, executives of vigor. Mill and Bonnie are almost impossibly thin. Possibly the most impeccably dressed character is actually the studio security chief, Stuckel. Even the waitstaff at Mill’s restaurants and his valets look audition-worthy, as is probably the norm in Hollywood.

The reputation is that young women are exploited here since the beginning, willing to pay a troubling price for a break. Theresa Russell indicated such real-life drama while casting for “The Last Tycoon,” a film also about a young movie executive. Altman implies that Mill has no trouble using female companionship as he pleases, but Altman stops well short of pursuing this subject for satire. It’s the 40- and 50-year-old males who get the shaft in this world, not 18-year-old hopeful starlets.

While skewering the creative process (or at least the authorization of it), Altman enjoys poking fun at what he considers Hollywood’s insignificant standards. There is male frontal nudity, not enough to draw an X rating but enough to be noticed. Not only is the word “tampons” said multiple times, one is actually shown and played with. Altman says in a DVD extra that the scene was improvised just before filming. Then there’s an animal that can be easily trapped that is beaten to death.

Visually, the crown jewel is Altman’s opening uncut sequence, but “The Player” suffers from its anchoring to restaurants and June Gudmundsdottir’s home. What lifts those potentially stagnant images are Robbins’ poses. Roger Ebert noted that from some levels, Mill resembles Orson Welles. Early in a pool, and then in his memorable couch scene, in which he has one-upped Walter Stuckel, Pasadena police and Bonnie Sherow, Mill resembles Tony Montana in several scenes of “Scarface.” In Tony’s early encounters with associates he sits slouched, defensive, shoulders slumped, but as he gains power his shoulders gradually rise. Mill after a harrowing moment also will appear in June’s window with a pained expression of entitlement, uncannily obnoxious.

Every other moment of “The Player” feels like an homage to something. So many of the in-jokes are so “in,” including the rationale behind the classic movie posters, that most viewers wouldn’t recognize them and would have to read about them to identify them all. Hollywood restaurants serve water in wine glasses, enabling one effective dining dis by Mill. Cher is apparently known for never wearing red; the Range Rover was the Hollywood yuppie’s vehicle of choice in the early ’90s. “The Player” figures to appeal most to the film “snob,” who will recognize many of the references and agree with Altman’s vision of Hollywood’s business arm making a mockery of powerful art, but that viewer is also likely to roll his eyes at the celebrity content.

It’s fairly late in the movie, around the 80-minute mark, when Griffin explains the end game to his secretary. He is duping Larry Levy into green-lighting a bad script that their boss, Joel Levison, will endorse. This will put both Levy and Levison in a bind.

In trying to fulfill Mill’s prophecy in one fell swoop, something feels missing, like an overdone cut. For expediency purposes, Altman has careers surging, and collapsing, on the same film. The demise of Joel Levison is almost ridiculous, generally the type of footnote listed in the credits after the film is done, but in this case it is necessary for him to get out of the way of the hero before the end, so we have another character telling us what happened, as Levison simply no longer appears in the movie.

Given the amount of people shown at the brainstorming and critique sessions, Mill’s plan is farfetched. Upstaging both Levy and Levison is so flimsy as visual dramatic material. There is no adequate way to show how this happens, but the surprise ending to “Habeas Corpus” somehow works.

Somewhere in here is a meritocracy. Mill is a creative person. Despite his boorish behavior, he seems to recognize what works. Altman suggests that Levison protected Mill — assuming that respecting Mill’s contract with Levy aboard wasn’t a form of dis — only to be backstabbed by him. Does “The Player” ultimately appreciate skill? It is conveyed that Griffin, more than the writers or the other executives, has engineered a hit that others would’ve ruined. Certainly there’s a valid argument that he deserves the big office.

“The Player” is drenched in unintentional irony. Pictures mentioned matter-of-factly in the film such as “E.T.” and “Pretty Woman,” which Altman presumably regards as fluff if not quality fluff, as well as stars such as Schwarzenegger or Costner, have entertained tens of millions, not all of them lowest common denominators. To denounce the merits of that in an attack on mainstream Hollywood represents an elitism that goes even beyond what those lowest common denominators tend to attribute to mainstream Hollywood. If Altman hates happy endings so much, why does he have Julia Roberts and Bruce Willis and Burt Reynolds and Sydney Pollack in this film?

Altman has been an enormously successful and acclaimed director, to the point he could persuade dozens of famous faces to show up for this project on union scale. So he’s irritated by untalented people who make obscene amounts of money. Is he aware of Wall Street banking, mortgage lending, pro spectator sports? In DVD commentary he hints at perhaps his greatest beef, crowing, “I created a Hollywood without agents,” explaining, “it’s like the basketball agents … they now run the business.” On some level “The Player” feels like a petulant ego trip.

The industry seems more understanding than Altman suggests, handing him and Tolkin Oscar nominations. Altman lost to Clint Eastwood, (“Unforgiven”), and Tolkin lost to Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (“Howards End”). There was a 3rd Academy Award nomination, for Geraldine Peroni, one of the film’s 2 credited editors; she lost to Joel Cox (“Unforgiven”).

Tolkin’s DVD commentary, interspersed with Altman’s but delivered independently, is hardly a ringing endorsement of Altman’s vision, though Tolkin faults himself for the novel-to-screenplay conversion. He disagrees with Altman’s suggestion that Whoopi Goldberg’s imagination made a scene out of Mill’s trip to the police station. It’s helpful when actors do that, Tolkin says, but no need to get carried away — “that doesn’t mean that they wrote the movie. They just contributed,” he insists.

Most telling is Tolkin’s assessment of the film’s treatment of the crucial noir. “Altman lost the sense of the writer and the police stalking Griffin … Altman lost it completely,” Tolkin says. Even in Hollywood, you can’t have a movie about the writers getting screwed without the writers getting screwed.

3.5 stars

(May 2013)

(Updated October 2019)

“The Player” (1992)

Cast: Tim Robbins as Griffin Mill ♦

Greta Scacchi as June Gudmundsdottir ♦

Fred Ward as Walter Stuckel ♦

Whoopi Goldberg as Detective Avery ♦

Peter Gallagher as Larry Levy ♦

Brion James as Joel Levison ♦

Cynthia Stevenson as Bonnie Sherow ♦

Vincent D’Onofrio as David Kahane ♦

Dean Stockwell as Andy Civella ♦

Richard E. Grant as Tom Oakley ♦

Sydney Pollack as Dick Mellon ♦

Lyle Lovett as Detective DeLongpre ♦

Dina Merrill as Celia ♦

Angela Hall as Jan ♦

Leah Ayres as Sandy ♦

Paul Hewitt as Jimmy Chase ♦

Randall Batinkoff as Reg Goldman ♦

Jeremy Piven as Steve Reeves ♦

Gina Gershon as Whitney Gersh ♦

Frank Barhydt as Frank Murphy ♦

Mike E. Kaplan as Marty Grossman ♦

Kevin Scannell as Gar Girard ♦

Margery Bond as Witness ♦

Susan Emshwiller as Detective Broom ♦

Brian Brophy as Phil ♦

Michael Tolkin as Eric Schecter ♦

Stephen Tolkin as Carl Schecter ♦

Natalie Strong as Natalie ♦

Pete Koch as Walter ♦

Pamela Bowen as Trixie ♦

Jeff Weston as Rocco ♦

Steve Allen as Himself ♦

Richard Anderson as Himself ♦

Rene Auberjonois as Himself ♦

Harry Belafonte as Himself ♦

Shari Belafonte as Herself ♦

Karen Black as Herself ♦

Michael Bowen as Himself ♦

Gary Busey as Himself ♦

Robert Carradine as Himself ♦

Charles Champlin as Himself ♦

Cher as Herself ♦

James Coburn as Himself ♦

Cathy Lee Crosby as Herself ♦

John Cusack as Himself ♦

Brad Davis as Himself ♦

Paul Dooley as Himself ♦

Thereza Ellis as Herself ♦

Peter Falk as Himself ♦

Felicia Farr as Herself ♦

Kasia Figura as Herself ♦

Louise Fletcher as Herself ♦

Dennis Franz as Himself ♦

Teri Garr as Herself ♦

Leeza Gibbons as Herself ♦

Scott Glenn as Himself ♦

Jeff Goldblum as Himself ♦

Elliott Gould as Himself ♦

Joel Grey as Himself ♦

David Alan Grier as Himself ♦

Buck Henry as Himself ♦

Angelica Huston as Herself ♦

Kathy Ireland as Herself ♦

Steve James as Himself ♦

Maxine John-James as Herself ♦

Sally Kellerman as Herself ♦

Sally Kirkland as Herself ♦

Jack Lemmon as Himself ♦

Marlee Matlin as Herself ♦

Andie MacDowell as Herself ♦

Malcolm McDowell as Himself ♦

Jayne Meadows as Herself ♦

Martin Mull as Himself ♦

Jennifer Nash as Herself ♦

Nick Nolte as Himself ♦

Alexandra Powers as Herself ♦

Bert Remsen as Himself ♦

Guy Remsen as Himself ♦

Patricia Resnick as Herself ♦

Burt Reynolds as Himself ♦

Jack Riley as Himself ♦

Julia Roberts as Herself ♦

Mimi Rogers as Herself ♦

Annie Ross as Herself ♦

Alan Rudolph as Himself ♦

Jill St. John as Movie Star ♦

Susan Sarandon as Herself ♦

Adam Simon as Himself ♦

Rod Steiger as Himself ♦

Joan Tewkesbury as Herself ♦

Brian Tochi as Himself ♦

Lily Tomlin as Herself ♦

Robert Wagner as Himself ♦

Ray Walston as Himself ♦

Bruce Willis as Himself ♦

Marvin Young as Himself ♦

Althea Gibson as Herself (uncredited per IMDB) ♦

Ted Hartley as Party Guest (uncredited per IMDB) ♦

Jack Jason as Himself (uncredited per IMDB) ♦

James McLindon as Jim the Writer (uncredited per IMDB) ♦

Derek Raser as Studio Mail Driver (uncredited per IMDB) ♦

Scott Shaw as Himself (uncredited per IMDB) ♦

Patrick Swayze as Himself (uncredited per IMDB) ♦

Dan Twyman as Funeral Guest (uncredited per IMDB)

Directed by: Robert Altman

Written by: Michael Tolkin (screenplay, novel)

Co-producer: Scott Bushnell

Co-executive producer: William S. Gilmore

Executive producer: Cary Brokaw

Producer: David Brown

Producer: Michael Tolkin

Producer: Nick Wechsler

Associate producer: David Levy

Original music: Thomas Newman

Cinematography: Jean Lepine

Editing: Geraldine Peroni, Maysie Hoy

Production design: Stephen Altman

Art direction: Jerry Fleming

Set decoration: Susan Emshwiller

Wardrobe design: Alexander Julian

Makeup and hair: Scott Williams, Deborah Larsen

Production executives: Claudia Lewis, Pamela Hedley

Production supervisor: Jim Chesney

Unit production manager: Tom Udell

Stunts: Greg Walker

Special thanks: Patrick Murray, Randy Honaker, Luis Estevez, Baseline, Suzanne Goldman, Toyoko Nezu, Reebok, Mark Eisen, Mimi Rabinowitz, Morgan Entrekin, Geoworks, Bally, Greald Greenbach & Two Bunch Palms, Bob Flick & Entertainment Tonight, Steve Trombatore & All Payments, Range Rover of North America, Marchon Marcolin Eye Wear, Spinneybeck Design America, Harry Winston Jewelers, L.A. Marathon, The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Janis Dinwiddie, Julie Johnston, Ron Haver, The Les Hooper Orchestra, The Bicycle Thief, Richard Feiner & Co., Inc.