‘The Wife’ has lots to say, and other than a couple arguing in a bedroom, nothing to show

There’s a lot to be said for a second opinion.

The most important scene of “The Wife” does not include its star, Glenn Close. A young woman who appears to be a talented writer attends a reception for an established female author and hears that not only does female writing go unpublished, the works that do get published go unopened.

Certainly, there is some truth in this statement. Absolute certainty? Not quite. Would the young woman weigh whether this established writer, whom she has presumably never before met, is only looking out for the young woman’s future happiness ... or perhaps trying to minimize the field of competitors in a cutthroat business?

The latter notion is too cynical even for “The Wife.” Also off the table is the prospect of a gifted young female writer having more than one college instructor and that one of those instructors might actually think she does elite work. She would seem to have plenty of options for marriage, but in “The Wife,” it’s somehow a field of one, and this is the 1950s, so ...

What did Mrs. Castleman ever see in this fellow? “The Wife,” reflecting its shaky approach to feminism, offers no excuses but no explanations. There is no chemistry between this young couple, simply availability. How many times has a professor dated a student; how many times has a director dated an actress. Yes. Remember in “The Godfather,” when Kay Adams is conveniently unhitched just when Mike’s back in town looking to build a little legitimacy? You’d think family members might raise red flags about this relationship, but that’s not exactly what the script is looking for.

“The Wife” also bears parallels to the unfinished story of “The Paper Chase.” A prized student is fascinated by her professor, this is how her life acquires ratification and meaning, and despite surely attending other classes and making an impression on other professors, her career will be determined by a jury of 1. Joan would be far better off taking the class of Julia Roberts’ Miss Watson in “Mona Lisa Smile.”

“The Wife” digs itself a monstrous hole on the first page, that being, movies about writers are terrible ideas. This is a strange addiction Hollywood can’t break. Is there anything that can be shown? No, everything must be told. Characters have to tell each other that so-and-so is an esteemed author and so-and-so is receiving an award and so-and-so produced a best-seller. Sometimes we run out of bystanders to say those things, so it’s up to the writers to recite their own credentials. People marveled in “Raging Bull” that De Niro can box, but do we know whether Jonathan Pryce or Glenn Close can write? No, and it doesn’t matter. Their cinematic son, David, is supposedly a writer too. Is he any good? Nobody knows or cares. He’s needed not to write a book but to illustrate (that’s an important word in short supply in this film) what a jerk his father is. The script here is so clumsy, it’s impossible to know whether David is mad because 1) Dad has not read his material or 2) Dad doesn’t like his material or 3) Dad didn’t coach his fourth-grade baseball team. (Note: Dad has another child he apparently doesn’t even maintain contact with.) In any case, David and Mom are mad about Dad for two wholly different reasons. And it doesn’t matter whether Dad’s a writer. Joe Castleman could just as well be a nuclear physicist, or economist, or diplomat who engineered a Middle East deal, and you’ve got the same movie.

A similar concept, “Big Eyes,” a 2014 film by Tim Burton starring Amy Adams, works better because the protagonist is a painter. That film, which covers a similar time frame as “The Wife,” suggests the alternative to Joan’s second-fiddle status and first-class life is a combination of fame, litigation and single-parenthood.

One of the loose ends of “The Wife” is the collaboration between the Castlemans. She will say that his characters are “wooden” (a fairly common term of reviewers) and his writing “stilted.” But evidently, he’s doing enough right in the category of inspiration. The film would have us believe Joan is doing the hard part, but that’s like saying Bill Gates did nothing while the programmers got the job done. Joe is a fraud but not a complete fraud. He’s talented, just overrated. He’s condemnable. But his collaborative material earned a Nobel.

Most disappointingly in “The Wife,” the great revelation occurs not in some beautiful, inspired scene, but in a bar, confirmed by flashbacks. Once again, it must be told, not shown, from the lips of an extortionist writer.

The flashback scenes show Joan and Joe in their 20s but lack any kind of spark. Close’s daughter, Annie Starke, looks the part, which is 90% of the battle, but Harry Lloyd doesn’t physically resemble at all the Joe that everyone is beginning to loathe.

Because Pryce and Close are not going to demonstrate literary magic, we’re left to refereeing their bedroom arguments. How many movies have resorted to such dreadful cliché ... well, just scratching the surface, there was Bergman’s “Scenes from a Marriage,” there was Nichols’ “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?,” there was Mazursky’s “Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice,” there was Payne’s “About Schmidt,” there was, more recently, Debra Winger and Tracy Letts in “The Lovers.”

Despite this massive handicap, “The Wife” is not a complete bust. It’s an intriguing premise. From the beginning, we see that while the couple experiences massive success, there is something else on Joan’s mind. These expressions delivered an Academy Award nomination for Glenn Close. Waiting for them to boil over, in the pin-drop atmosphere of a Nobel ceremony, is decent suspense. But what is at risk here? A disproportionate amount of embarrassment and shame, as any elevation of Joan would not offset the demise of Joe. But these characters are already in their 70s, presumably retired or semi-retired and famous. Is it plausible that Joan reaches her breaking point upon simply hearing the term “Nobel”? This partnership was cemented decades earlier. Joe and Joan seem to be getting along fairly well. They still have sex in the middle of the night. There’s no hint of divorce. Joan’s victory seems little more than revealing a secret to her children that one of them already knows.

The superior format of “The Wife” clearly would be the book (it is based on the work of Meg Wolitzer) or a stage production. But the gold standard is filmdom, and if an idea can garner Hollywood financing, you take it, especially when the movie is capable of producing an Oscar.

“The Wife” needs something, anything, to get the camera out of the bedroom. The Swedish director, Björn L Runge, can’t do it. He grasps strangely at cigarettes and a young hostess for anything photogenic. He really likes the Concorde but makes the seating look like coach on a 737, and two or three times in very uninspired footage, he demonstrates how clumsy it can be to have a conversation on a jet. The external pressure on the characters comes in the form of Christian Slater’s Nathanial Bone, apparently a salacious biographer who has sensed a story here for some time. Somehow, despite not actually having an apparent book deal, he is granted a Concorde flight; that’s a generous publisher. He doesn’t have any pictures or documents, just a savvy opinion he wants to test in a bar. As the script struggles with its feminist case, such are its uncertainties that it’s debatable whether Bone is the hero or villain of the picture. The ending suggests he has the right story but is not the right emissary and, despite his detective work, can’t or won’t be allowed to report his impressive findings. (Note 1: Salacious book authors enjoy being sued.) (Note 2: Joan’s threat to Bone paves the way for David to write the family tell-all, which surely would be the best-seller he covets.)

The film never asks an intriguing question: If a woman writes an anonymous paragraph and a man writes an anonymous paragraph, what percentage of readers will correctly guess which was written by a woman and which by a man? Is writing completely gender-neutral? It doesn’t seem like it could be, but maybe it has never been studied, perhaps for the results it might reveal.

More filler is provided by speeches about off-camera figures. An important person has a baby, which proves an annoying interruption to the trip. If Close does not win the Oscar, her reaction to this event could be the reason why. We’re told Joe’s ex-wife is a psychiatrist and that she’s conveniently good with whatever happened in Joe’s life. A psychiatrist or psychologist might in fact be very interested in Joan’s life. Is she passive-aggressive? Resigned to victimhood?

An amusing byproduct of “The Wife” is the stoic Nobel committee. They’re about to hand a prestigious award to a con artist. How well is the Nobel literature prize researched, and what exactly does it represent? It is, it appears, a lifetime achievement award, intentionally diversified by geography and specialty, bestowed upon people who have been vetted for decades by the masses. Most people could probably not name more than 3 winners of the past 50 years; many couldn’t name any. Probably the greatest obstacle to Joe Castleman’s honor is his nationality. Few Americans have won it, though Bob Dylan accepted the 2016 honor by having his speech read by someone else. Based on “The Wife,” perhaps the awards are a bigger deal to the committee than they are to the recipients. The committee provides a stunning young woman to serve as a hostess for Joe Castleman in the way universities send girls out to greet football and basketball recruits. This bit of flirtation by Runge is a bust.

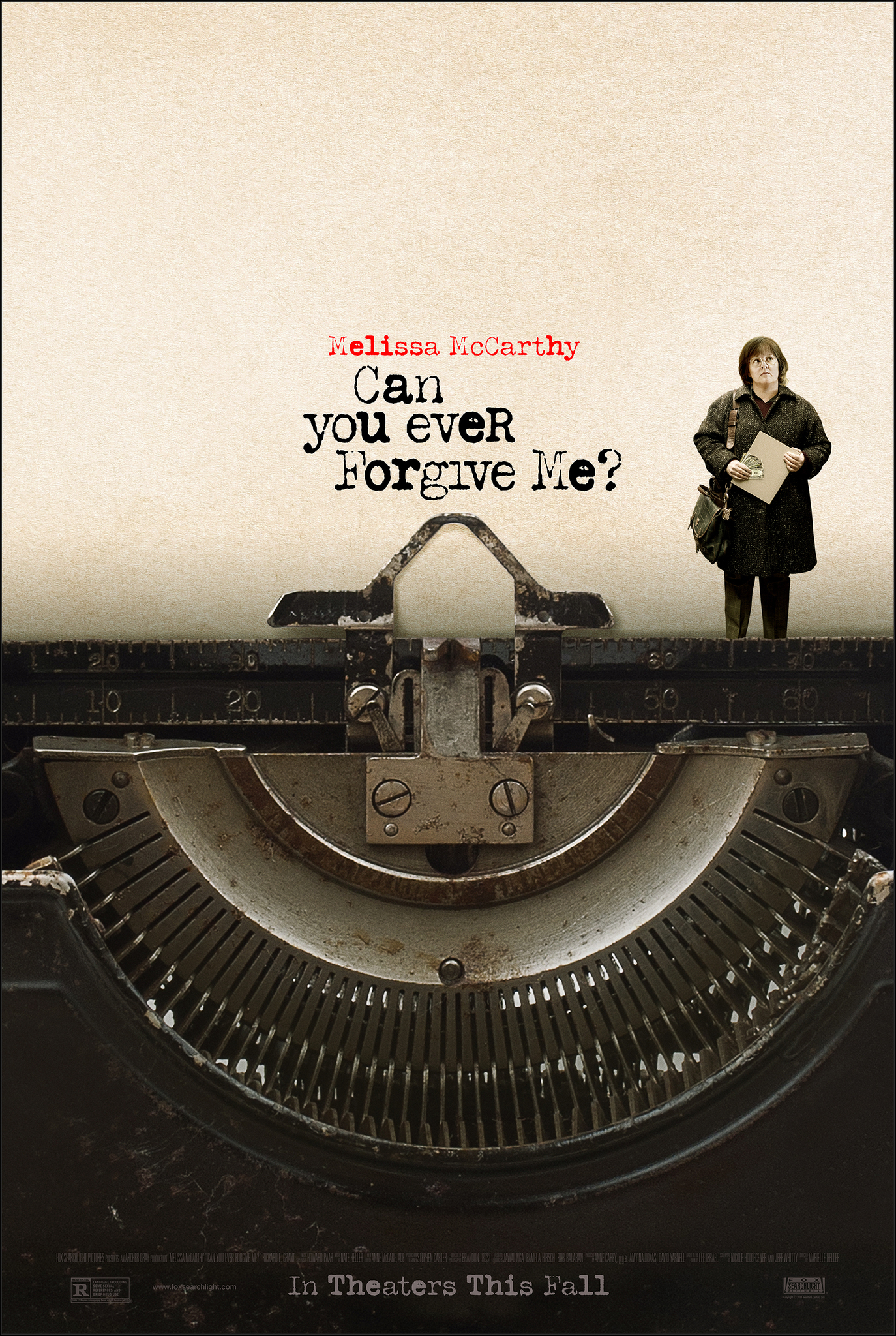

“The Wife” brings to mind two movies of the same season. Clint Eastwood’s “The Mule” is also about a lothario who made serious mistakes, owned up to them and accepted the consequences. On the other hand, “Can You Ever Forgive Me?” depicts an author committing fraud with no reservations. Her victims, like the Nobel committee in “The Wife,” are the laughable suckers who don’t deserve any better; the film cheers her for beating the system.

The ending of “The Wife” could imply that Joe was done in by his fraud, that his appropriation was not stress-free. Or it could imply that he willed his demise to happen, recognizing his marriage was over and wanting to spare his family any more pain. Not said in the movie is the fact that to collect the Nobel’s 8 million krona prize, a recipient must deliver a lecture within 6 months of receiving the award, something Joe Castleman couldn’t have done. Presumably they would waive that rule in this case — or ask Joan to make the speech on his behalf. How fitting.

2 stars

(February 2019)

“The Wife” (2017)

Starring

Glenn Close

as Joan Castleman ♦

Jonathan Pryce

as Joe Castleman ♦

Max Irons

as David Castleman ♦

Christian Slater

as Nathanial Bone ♦

Harry Lloyd

as Young Joe ♦

Annie Starke

as Young Joan ♦

Elizabeth McGovern

as Elaine Mozell ♦

Johan Widerberg

as Walter Bark ♦

Karin Franz Körlof

as Linnea ♦

Richard Cordery

as Hal Bowman ♦

Jan Mybrand

as Arvid Engdahl ♦

Anna Azcarate

as Mrs. Lindelöf ♦

Peter Forbes

as James Finch ♦

Fredrik Gildea

as Mr Lagerfelt ♦

Jane Garda

as Constance Finch ♦

Alix Wilton Regan

as Susannah Castleman ♦

Nick Fletcher

as King Gustav ♦

Mattias Nordkvist

as Dr Ekeberg ♦

Suzanne Bertish

as Dusty Berkowitz ♦

Grainne Keenan

as Carol Castleman ♦

Isabelle von Meyenburg

as Nobel Hostess ♦

Morgane Polanski

as Smithie Girl Lorraine ♦

Twinnie-Lee Moore

as Flight Attendant Monica ♦

John Moraitis

as Lovejoy ♦

Michael Benz

as White ♦

Johanna Andersson

as Hotel Manager ♦

Catharina Christie

as Hotel Doctor ♦

Carolin Stoltz

as Hotel Nurse ♦

Håkan Pettersson

as Gustav ♦

Ossian Skarsgård

as Young David (voice)

Directed by: Björn L. Runge

Written by: Jane Anderson (screenplay)

Written by: Meg Wolitzer (novel)

Producer: Jo Bamford

Producer: Claudia Bluemhuber

Producer: Rosalie Swedlin

Producer: Meta Louise Foldager Sørensen

Producer: Piers Tempest

Co-producer: Piodor Gustafsson

Associate producer: Georgia Bayliff

Line producer (Sweden): Johanna Lind

Executive producer: Jane Anderson

Executive producer: Gero Bauknecht

Executive producer: Nina Bisgaard

Executive producer: Mark Cooper

Executive producer: Florian Dargel

Executive producer: Tomas Eskilsson

Executive producer: Hugo Grumbar

Executive producer: Tim Haslam

Executive producer: Jon Mankell

Executive producer: Björn L. Runge

Executive producer: Gerd Schepers

Music: Jocelyn Pook

Cinematography: Ulf Brantås

Editing by Lena Dahlberg

Casting: Elaine Grainger, Susanne Scheel

Production design: Mark Leese

Art direction: Caroline Grebbell, Paul Gustavsson, Martin McNee

Set decoration: Craig Menzies

Costumes: Trisha Biggar

Makeup and hair: Andrew Simonin, as Siân Turner Miller, Caroline Hamilton, Madeleine Törnqvist af Ström, Charlotte Hayward, Rachel Lennon, Sara Klänge, Helene Norberg, Caroline Peberdy, Yenifer Rojas Sanchez, Maurine Tugavune

Production manager: Claire Campbell

Post-production supervisor: Michael Sevholt

Stunts: Robbie Keane, James McCreadie

Thanks: Gero Bauknecht

Thanks: Stellan Skarsgård