‘The Way We Were’ rides

title wave to immortality

It’s more than just the song.

It’s the title, too.

And oh yes, some of Hollywood’s greatest talent.

“The Way We Were” (the song) is the 2nd-most effective piece of film music ever composed. Permanently established among the world’s greatest love songs, it’s a lifeline to a cinematic production lost at sea.

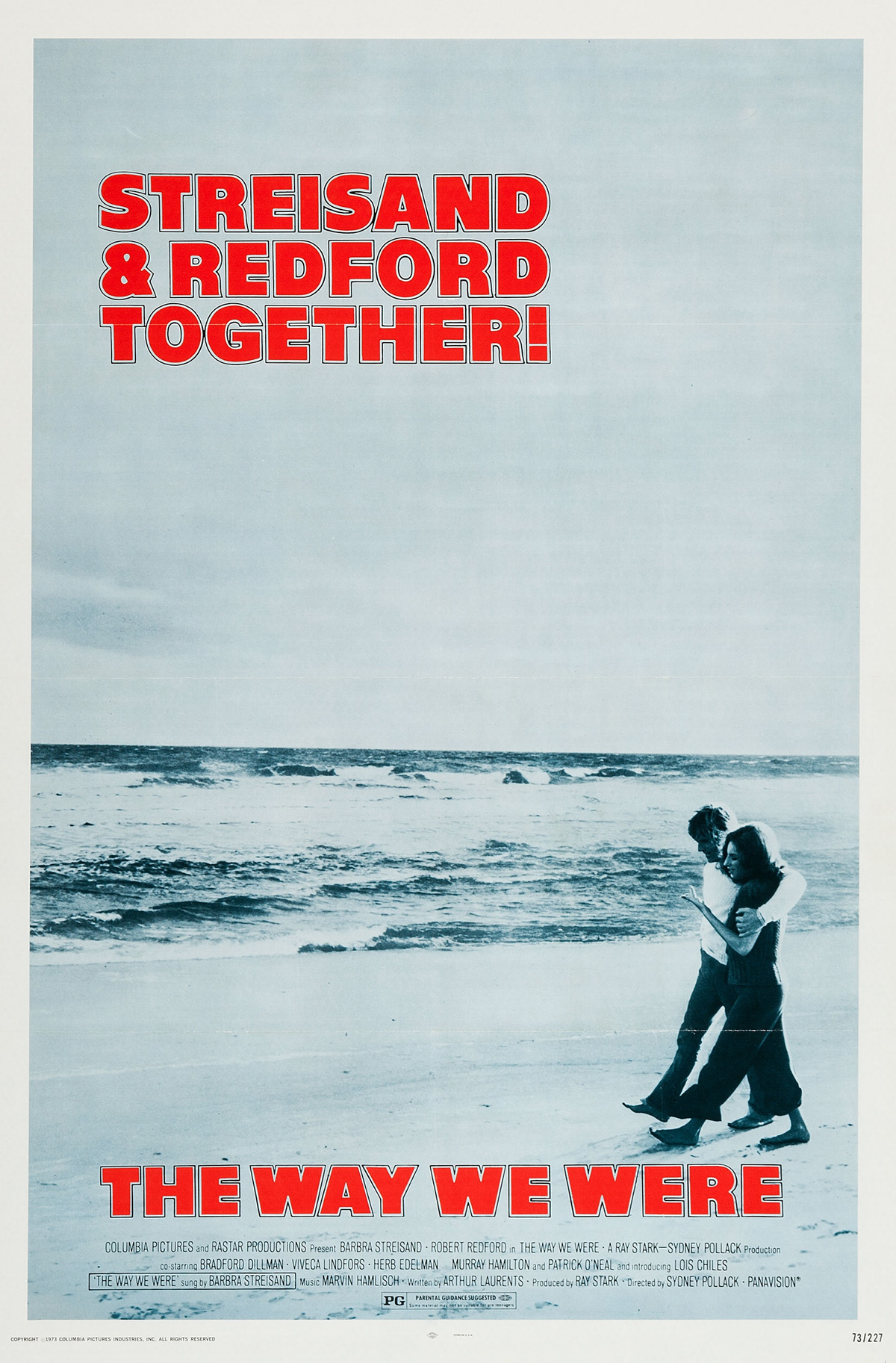

It’s not like the world doesn’t know this. Marvin Hamlisch won an Oscar for it. The lyrics were written by Marilyn and Alan Bergman, who appear in the Oscar-night photo above with Hamlisch and (obscured) Ann-Margret. Hamlisch won, remarkably, two other Oscars in the same ceremony, for scores for “The Way We Were” and “The Sting.” He was 29, far less well-known than Barbra Streisand and Robert Redford, the two megastars whose job it was to carry this Sydney Pollack/Ray Stark picture.

The film does not open with the song but the score; the song kicks in beautifully at the five-minute mark after the audience has been introduced to Streisand’s Katie Morosky and has just noticed Redford’s Hubbell Gardiner at a packed restaurant. Hubbell might as well have remained in this pose — a trance-like state — for the entire movie. Hubbell apparently is well aware that Redford took the role grudgingly, regarding the film as a Streisand vehicle (or “another Ray Stark ego trip”). Perhaps he just didn’t believe it. No one should. These are two different kinds of actors, and these characters have no business together. What’s more, they have all the means to know it.

In a remarkably comprehensive interview (copyright 1999) on “The Way We Were” DVD, Pollack states, “I spent more time trying to convince Redford to do this picture than I’ve ever spent in my life with- on anything.” In the DVD commentary — sort of like the film interviewing the director — Pollack contends Redford “wasn’t such a romantic symbol” before this film, and, “I do believe ‘The Way We Were’ was a pivotal picture in terms of his image as a romantic leading man.”

Pollack talked Redford into it, Pollack says, because he considered Redford a “vital, vital element” to this Arthur Laurents story. Streisand got top billing. Redford does not appear in DVD interviews, perhaps a sign this is not his favorite work.

A newspaper ad for "The Way We Were" in late October 1973,

during the movie’s gradual nationwide release, including

comments from Pauline Kael (top), Judith Crist, Bruce Williamson

and Jeffrey Lyons (left column), Rex Reed (middle), and Ed Miller,

Bernard Drew and Norma McLain Stoop (right column).

In an even more comprehensive recollection about the making of “The Way We Were,” Streisand in October 2023 released a book excerpt in which she says Redford turned her down a couple times, but Pollack fought for him too; “He was as persistent as I was.” According to Streisand, Redford complained to Pollack about the script; “Who is this guy? He’s just an object…. What does this guy want?” Perhaps art and life would imitate each other in this movie; to borrow a title from a much later movie, maybe the tagline for “The Way We Were” is He’s Just Not That Into You/This.

Streisand writes that Redford was even skeptical of the song, as she acknowledges, “I know the song contributed enormously to the movie’s success, yet Sydney told me that Redford didn’t want me to sing at all.”

A subtle reason for the film’s endurance is that it thrives on a lead female character. This is rare even today for a big-budget film, all the moreso that the character is decidedly ethnic. Laurents calls Streisand “the first and I think only openly Jewish movie star.” She received an Academy Award nomination, somehow one of only two for acting in her career. She lost to Glenda Jackson, “A Touch of Class,” though she previously achieved an Oscar by tying Katharine Hepburn for her performance in 1968’s “Funny Girl.” Laurents says Katie is based on a Jewish girl he knew in college, and “Barbra instinctively ... understood this girl.” She’s unafraid of lost causes. Men may wonder why Hubbell can’t just get his (bleep) together, but women will shed tears over Katie’s unflinching effort to bring out his best.

She’s Jewish; he’s a WASP. She’s a radical leftist; he’s the establishment. She frowns; he smiles. Family concerns are out of the picture; Katie and Hubbell exist without parents or siblings.

But they’re stuck. In the universe of “The Way We Were,” there’s virtually no one else to date. Katie faces one rival, Carol Ann (Lois Chiles, who got the “introducing” tagline). Katie is well known around campus, but Hubbell (a character thought by Roger Ebert to be based upon the writer Peter Viertel, coincidentally Jewish) is the only one among his group of friends mildly interested in her. We learn early that Hubbell is not only a champion athlete but perhaps the top dog in the classroom. Katie is troubled by the latter revelation, viewing it as a personal defeat.

(Chiles, coincidentally, also would find herself the third wheel among a couple who have no business together about 14 years later in “Broadcast News.”)

Perhaps anticipating its own awkward ending, “The Way We Were” reveals a strange discomfort with marriage. In his 1973 review, Roger Ebert says the couple indeed “get married.” But there are no scenes of a wedding, and if one pays close attention to the ring situation, it’s curious. Evidence suggests the two really are married, but there’s license to believe otherwise. Streisand in her 2023 memoir declares, “... we see Katie setting a bride-and-groom cake topper on a shelf in their beach house. So we know they’re married and they’ve moved to LA, and it’s all done without words, in a few shots. (Nice work, Sydney.)”

Pollack concedes in the DVD commentary that going quickly to a very long flashback, and then proceeding ahead, is a “rather odd structure” that “felt oddly shaped.” The film spans 15-20 years, but while Streisand ages beautifully, Redford seems too old for a collegian, an observation of Pauline Kael. We see Hubbell is clearly the top catch on campus — champion athlete, acclaimed writer, handsome. He will prove to be an empty suit (though he almost never wears one) and underachiever and sellout, but — likely by accident — Redford and Pollack have stumbled into one of the more convincing portrayals of an American elite. Everyone knows someone like Hubbell Gardiner. He apparently has it all. You want to be him or hang out with him. If you do, you realize, there’s not really much there, and discerning observers will know that life is a lot more interesting around the Katies. (Admittedly, it is a bit odd to see Hubbell in a few scenes drinking alone.)

Katie’s appeal is her sincerity and fairness. You know what you’re getting, and for most males, it’s a bit too much. No other man seems particularly interested; colleagues treat her as one of the guys, which bears another faint parallel to “Broadcast News” in the form of the Holly Hunter-Albert Brooks situation.

But males who dismiss Katie are making a mistake. Among her best scenes is her assessment of Hubbell’s first book. Her critique — that he is too distant from his characters — is hardly unique for a movie about an author ... but it’s the way she says it, the same way Streisand will analyze Nick Nolte two decades later in “The Prince of Tides.”

In the best scene of the film, Streisand gingerly climbs into bed next to an exhausted Hubbell, and Pollack, the Michelangelo of Mainstream, delivers his own magic, an overhead shot of Streisand’s gorgeousness never exposed in the rest of the movie. Pollack says in DVD commentary that he “worried a lot” about the scene appearing “comic in a bad way.” We all may not know Streisand, but we know people like Katie — devastatingly attractive while they try hard not to be. Something about her suggests she’ll be a great wife even for someone who has no idea Spain had a civil war. Hubbell, it’s clear, really is smarter than the other guys.

“The Way We Were” was the brainchild of Laurents, whose credits include screenplays for “Rope” and “The Turning Point” and the book for “West Side Story.” “The Way We Were” is semi-autobiographical material of Laurents’ experiences at Cornell and during Hollywood’s Red Scare. One wonders what the original draft looked like. He said that at first glance, Stark and Streisand loved it and wanted the script yesterday. Redford proved to be a thorn. He obviously disliked the character written for him.

According to an article in the April 8, 1974, edition of the Chicago Tribune, Laurents had just told the Toronto Sun, “I’m very hot right now, but only because the picture is hot. Redford had me fired from the picture. They called in 11 writers and then they called me back to patch it up again. Redford refused to say one particular line; said it would hurt his image. Remember the scene where he’s drunk and he makes love to her [Barbra Streisand] without really knowing what’s going on? When we got to the second love scene, he was supposed to say: ‘It’ll be better this time.’ That was the line he wouldn’t say. Apparently Robert Redford is never bad.”

Whoever made the call, Laurents indeed was fired, and Pollack brought in a revolving door of elite writers, including Dalton Trumbo, before rehiring Laurents. (Alvin Sargent is credited by Pollack in the DVD interview and by Pauline Kael in her review.) Streisand in her 2023 memoir says, “The fact is, Sydney didn’t like Arthur ... that’s why he brought in his own writers ... and Arthur didn’t like Sydney.” Laurents is said to have come up with the name “Hubbell” from an advertising exec he admired.

A far more important name is the title. It is beautiful, elegant, concise, perfect for film and perfect for song. Pollack says in the DVD commentary that it has “a sense of memory.” What does it mean? Nothing that really has anything to do with the film. It implies a couple longing for a quieter, more compatible past. The key is the tense of the last word. It indicates something is finished and was once great. If that word were present tense, it would imply an ongoing challenge to remain compatible.

Who wrote this title? No one thinks to address this in the DVD interview. Laurents, Stark and Pollack are all deceased. Because there is no definitive, accessible evidence as to who wrote the title, Laurents will receive the credit here, though it’s within the realm of possibility that it came from Stark.

There are notable Hollywood disasters that got a lot of money and a lot of expertise and a lot of meddling and still failed mightily. “The Way We Were” is the opposite side of that, proof that if you throw enough talent together on a shaky foundation, something good can happen.

Pollack says three scripts were written for a sequel, but none felt right.

Nearly 20 years later, Streisand helmed “The Prince of Tides,” an alternate take on “The Way We Were” concept based on Pat Conroy’s hit novel. She directed, produced and starred. Again, she will try to guide a handsome, blond, non-Jew to realize his better self, only this time, she’s more successful. “Tides” probably shouldn’t work — the important therapy case is barely an afterthought — but like “The Way We Were,” it does, equally if not even more watchable as an episodic feast. Unlike “The Way We Were,” there is no unforgettable melody.

Pollack would direct Redford in a later film, “The Electric Horseman,” also produced by Ray Stark, in which two people are perfect for each other, but only for a week, then they know it’s over, a sentiment coincidentally revealed in “The Prince of Tides.”

Beyond a stubborn mutual admiration, Hubbell and Katie are never right for each other, but they can’t help but wing it, each is a nice change of pace from their cardboard colleagues. Perhaps a big reason Redford supposedly disliked his character is that Katie is given numerous statements and platform that indicate her intelligence and world view, while Hubbell is limited to writing.

What does a writer act like when he’s not writing? Showing that a character is a gifted writer is a frequent challenge of filmmakers. In “Trumbo,” we see a confident person smiling in a bathtub; no one who’s bad would resort to this technique. For Hubbell, Pollack chooses to have a professor announce his skill in class and read a couple sentences. “In a way, he was like the country he lived in. Everything came too easily to him. But at least he knew it. About once a month, he worried that he was a fraud ...” Redford’s expression here of satisfaction and modesty is impressive.

“The Way We Were” struggled with critics, largely for its messy second half. Its Rotten Tomatoes rating (albeit with few samples) is only 63%. Vincent Canby in 1973 called the film a “sellout” that gets “turned into junk” when Katie and the plot go their separate ways. Roger Ebert gave it 3 stars but complained “the movie suddenly and implausibly has them fall out of love.” Gene Siskel didn’t even mention the music and, in a 2½-star assessment, shrugged that “it’s Mr. Dreamboat paired with Ms. Kook.”

Pauline Kael called it “a torpedoed ship full of gaping holes which comes snugly into port” and wrote that the dramatic change “hardly makes sense,” but she decided “the damned thing is enjoyable” and concluded it’s “hit entertainment” and “maybe even memorable entertainment,” though it’s “a terrible movie.”

Kael complained that “the cinematography is ugly.” Cinematographer Harry Stradling Jr. received an Oscar nomination, losing to Sven Nykvist (“Cries & Whispers”).

Pollack, in the DVD interview, recalls the Kael review with his own interpretation: “Pauline Kael’s review was interesting. She, she wrote what for her was a pretty good review. I mean, she certainly said it worked. She said it shouldn’t have, but, you know, but she says it’s amazing in how it- you know, it’s like a boat, she said, she made this analogy of a boat that’s full of holes, sinking, but it makes it very safely into port, or something. It’s some weird analogy; it was a backhanded compliment.”

Critics’ chief argument was not the look of the film or unusual flashback structure but the speed of the deteriorating marriage in the latter hour. Indeed, something feels missing.

Streisand in the DVD interview and especially in her 2023 memoir complains about the cutting of several scenes, one of them powerful (it is included on the DVD at her request). It shows Hubbell telling Katie in an intense conversation that an old college friend “informed on you,” implying Katie might have to do something similar. Laurents explains that he was trying to convey, “Either she informs, or he is fired.”

That is quality drama. But does it fit? It’s hard to believe someone would have to “inform” on Katie given what we know of her college background. It would be like someone telling the feds, “Pssst — George Bush is a Republican.”

In the DVD interview, Streisand says, “The way the movie is now, without those two scenes, it’s um, it seems like, uh, we broke up because he slept with another girl once.”

But after that scene, Pollack says, when they tried to “start it over again” on a political level, the test audience “literally” got up to go for popcorn “in droves.”

Pollack concedes that the film is not a “thorough” examination of the blacklist era. He likens that element to filming people living near Auschwitz talking about Auschwitz and defends the cuts of the “political” material. He was evidently content that there’s enough external pressure depicted to make the unlikely marriage impossible.

He explains, “We had two previews in San Francisco ... it was a flop on a Friday night; it was a hit on a Saturday night. .. We just whacked seven or eight minutes out of it and stuck the two pieces together, and that was it, it was a hit. ... We didn’t change anything. We just took out about five scenes. And they were all politics.”

Later, Pollack says he isn’t sure how many minutes were cut. Stark, in a snippet of DVD commentary, says 15 minutes were cut.

On the other hand, Streisand in 2023 writes, “(By the way, my manager, Marty Erlichman, was there and he says the picture played great on both nights.)” There’s some new drama — how did that first SF preview really go? Like Stark, she says 15 minutes were cut. She approves of cutting three scenes, not two others.

At one point over an early scene in the DVD commentary, Pollack explains, “It would be so easy to make a movie if all you did was cut the bad scenes. That’s not the hard part. The question is, do you need it ... you have to be brutal.”

“You know, the problem with movies is, you don’t- you try not to do show and tell,” Pollack continues. “You try to either show, or tell. You try to show, always, and if you can’t show, the last resort, you tell. But, but you try desperately not to do both.”

“The climax is missing,” Laurents complains, but “nobody cared.”

What of the ending? Pollack sweeps through a new baby, a permanent breakup and a years-later reunion in six whole minutes. Katie and Hubbell will see each other in a chance encounter outside a Manhattan hotel; each smiles at the other as though they were old college buddies who never experienced the latter 90 minutes of the film. In a ghastly line, he actually asks, “Still married?” Streisand cheerfully converses and then hustles across the street as if she wanted to wrap this film as fast as possible. She twice says “David X. Cohen,” and both times, it is unintelligible. It seems Katie has the right to hate Hubbell, but she bestows on him a virtual victimhood, as though she simply feels lucky that this relationship lasted as long as it did.

Then, incredibly, Pollack unleashes another moment of magic. Katie tells Hubbell, “Your girl is lovely, Hubbell,” and for a fraction of a second, we think she is talking about the disappearing baby, but then Katie makes clear she is talking about Hubbell’s significant other, and when Redford looks at Katie and says “I can’t,” we have one of the greatest moments of ’70s cinema, and somehow, this dubious ending succeeds.

Pollack says there is “real value” in “a lot of these scenes” that were cut, but he wanted a “certain amount of pace ... I think there’s a cleaner line emotionally to it the way it is now.”

Aside from the song and title and stars, a part of the film’s long-term appeal is its fantasy nature and gentility with troubling subject matter. Imagine having a lucrative Hollywood career. “The Way We Were” rationalizes itself the same way wealthy or famous people rationalize their problems. If you’ve got a house on a Malibu beach and regular movie work, walking away from your wife and child (or being on the receiving end of that) isn’t really a deal-breaker for anything. Failed marriages are speedbumps. Nor is it a catastrophe if your spouse’s friends can’t stand you or even go to jail under unfair circumstances. The movie, like “10” of a few years later, indicates that entertainment elites are in another zone, that when you don’t have to worry about money or status, a lot of typical human grievances don’t matter, and that’s appealing. “The Way We Were” is a mushy throwback film to Old Hollywood, yet Pollack is informing us about the (non-)concerns of a rock-star lifestyle.

The list of Oscar-winning tunes for best original song is stronger than you probably think. “White Christmas,” “Over the Rainbow,” “Moon River” and “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” are among the ones you’ve heard (many times). None of them reached down, like Cary Grant’s arm at the end of “North by Northwest,” and catapulted a scattershot project into immortality like Hamlisch’s work.

No musical composition has had such an impact on a film, other than Vangelis’ score of “Chariots of Fire,” which delivered the grand prize, a Best Picture Oscar. (John Williams’ score for “Jaws” would probably take third.)

Pollack says Hamlisch wrote the melody “before he ever came to see me.” Pollack says Hamlisch was “new at the time” but had a “fix” on the concept and “sort of knocked me out with the song right away.” Pollack says he did have concerns the song wasn’t “complex” enough, maybe “white on white.” He says they did an alternate, more “complex” version that Streisand called “The Way We Weren’t” and that validated the power of the original. The alternate exists on a recording.

Barbra Streisand attended the 1974 Oscars but only watched backstage,

according to this account in the Chicago Tribune.

Hamlisch would achieve EGOT status and enormous career acclaim. He received his Oscars for “The Way We Were” at age 29; his work was heard in dozens of films afterward. Nor was Hamlisch infallible — he was also the composer behind the 1989 Oscars’ Snow White/dancing tables fiasco.

The Bergmans state in the DVD interview, and Streisand confirms, that Streisand changed one word of the song — the first word, which had been “Daydreams,” into “Memories.”

Sometimes, long-term appeal can fool the greats. In her review of “The Way We Were,” Pauline Kael slammed the “whining title-tune ballad” that “embarrasses the picture in advance.” Really? She says the film has the “excruciating score of a bad forties movie.” Many are still blissfully excruciated whenever this one turns up on cable. “The Way We Were” is not a 4-star film. But those four words are with us forever.

3.5 stars

(January 2018)

(Updated March 2019)

(Updated November 2023)

(Updated June 2024)

“The Way We Were” (1973)

Starring

Barbra Streisand as

Katie ♦

Robert Redford as

Hubbell ♦

Bradford Dillman as

J. J. ♦

Lois Chiles as

Carol Ann ♦

Patrick O’Neal as

George Bissinger ♦

Viveca Lindfors as

Paula Reisner ♦

Allyn Ann McLerie as

Rhea Edwards ♦

Murray Hamilton as

Brooks Carpenter ♦

Herb Edelman as

Bill Verso ♦

Diana Ewing as

Vicki Bissinger ♦

Sally Kirkland as

Pony Dunbar ♦

Marcia Mae Jones as

Peggy Vanderbilt ♦

Don Keefer as

Actor ♦

George Gaynes as

El Morocco Captain ♦

Eric Boles as

Army Corporal ♦

Barbara Peterson as

Ashe Blonde ♦

Roy Jenson as

Army Captain ♦

Brendan Kelly as

Rally Speaker ♦

James Woods as

Frankie McVeigh ♦

Connie Forslund as

Jenny ♦

Robert Gerringer as

Dr. Short ♦

Susie Blakely as

Judianne ♦

Ed Power as

Airforce ♦

Suzanne Zenor as

Dumb Blonde ♦

Dan Seymour as

Guest

Directed by: Sydney Pollack

Written by: Arthur Laurents

Producer: Ray Stark

Associate producer: Richard Roth

Music: Marvin Hamlisch

Cinematography: Harry Stradling Jr.

Editing: John F. Burnett

Production design: Stephen Grimes

Set decoration: William Kiernan

Costumes: Dorothy Jeakins, Moss Mabry

Makeup and hair: Kaye Pownall, Donald Cash Jr., Gary Liddiard

Unit production manager: Russ Saunders