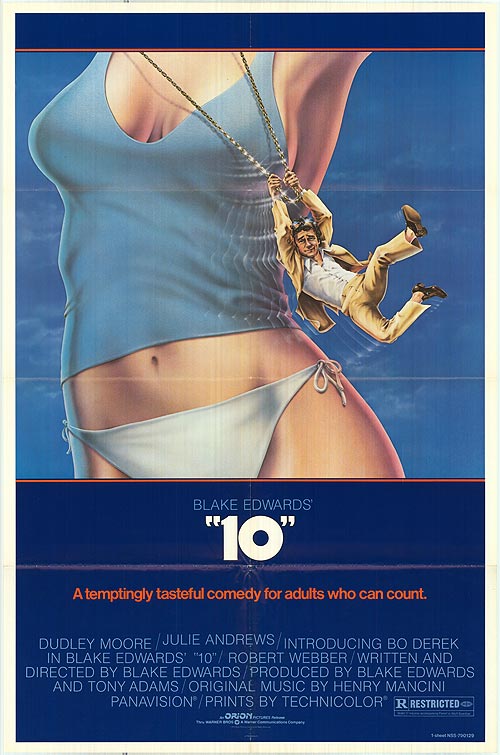

Blake Edwards tries his best to make a 7, ends up with a pop culture ‘10’

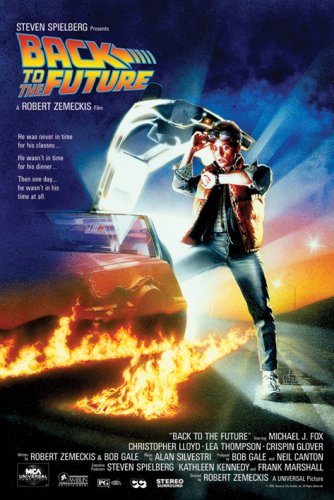

Life plays curious tricks. One is that kids often wish they are adults and adults often wish they were kids. Numerous films, probably most famously “Back to the Future,” take a stab at straightening out these notions: We’re all meant for our time.

Another of life’s tricks is that a wealthy, healthy and famous Hollywood composer actually can be bored and unhappy. That is the understanding of Blake Edwards’ “10” and specifically the lead character, George Webber, who at 42 is tired of his spectacular career, tired of his girlfriend and even growing tired of his frisky Beverly Hills neighbors.

Apparently, success fatigue can produce the most remarkable of daydreams. With barely a hint, “10” uncorks not just one of the most famous scenes in movie history but perhaps the single most famous scene in movie history, a crowning symbol of pop culture and, paired with the film’s devastating title, the relevance of cinema.

At 80 minutes into the film, the vision of 22-year-old Bo Derek running across a beach almost seems to happen accidentally. We are briefly teased as George and Jenny make eye contact, point apparently made. Then we’re interrupted by the help. Edwards enlists several more poses before a dream, or fantasy interpretation, takes shape. Many other films show women in bathing suits. This scene enters the category of unforgettable because of two little enhancements: slow motion and cornrows.

Incredibly, it’s an earlier scene, with far more clothing, that was the inspiration for “10.” Edwards is said to have noticed at a stop sign in Brussels a bride in the next car en route to her wedding; he entertained the notion of a male fantasizing about her and pursuing her. Indeed, that is how we meet Derek in “10” — as the bride-to-be Jenny, at a stop sign in a car, only her face visible. Introducing Jenny to viewers this way is a curious decision by Edwards, who opts to give us several looks at her before finally playing his trump card. Perhaps he just didn’t know what he had.

Apparently, neither did the critics. The Washington Post’s Gary Arnold, in his skeptical 1979 review, does not even mention the famous scene. Roger Ebert, in a 4-star review, also ignores the seminal moment and claims “The central treasure in the film is the performance by Dudley Moore.” The same goes for The New York Times’ Vincent Canby, who praises the comedy and believes “The movie belongs very much to Mr. Moore.”

Clearly the film does not belong to Julie Andrews, who is actually its biggest star. She was also Edwards’ wife. According to TCM, “10” proved “a significant film” for Andrews, “demonstrating that she could pull off a sexy role in an adult comedy.” The “sexy” part is debatable. Arnold’s review notes, “Sam is required to deliver glib, profane dialogue that sounds peculiarly disconcerting coming out of Andrews’ mouth and general photogenic essence.” Indeed, this beloved matinee heroine is reduced to a nag, unable to straighten George out and relegated to waiting for him to come around on his own. A bedroom argument over the term “broad” is insufferable. Very early, in the most unconvincing line of the film, she is compelled to tell George, “I think the last two years have been rather good.” It’s impossible not to watch Julie Andrews in this film and conclude, “She can do a lot better.”

(In the opening credits, Moore’s name is on the left and Andrews’ is on the right, but Andrews’ is elevated, apparently inspired by the egalitarian labeling for “The Towering Inferno.” Also in the credits, John Isaacs of MichaelJohn is credited for Andrews’ hair, but no such distinction is granted for Derek’s legendary coif.)

Observers of this project in the late ’70s probably would’ve given “10” the potential of a 5. Edwards, who took a workmanlike path to Hollywood elite (he passed away in 2010), was best known for his fading ’60s “Pink Panther” hits. According to Derek in 2013, “10” was only done by Edwards as a contractual obligation for landing another film. (The TCM account suggests the opposite.) The original “10” lead, George Segal, was to play a dentist before he walked out in a dispute with Edwards. Then came Moore, who happened to be an accomplished pianist, so George Webber was reinvented as a celebrated composer.

This professional change proved a gift of unrealized potential. Writers, for example, are terrible movie protagonists, but a musician can be depicted, through some beautifully placed melodies or laughable refrains, as alternately stalling, struggling, stumbling and soaring. In a few sweet moments, Edwards puts George at a piano, and there is magic. Henry Mancini’s soundtrack evokes a sweetness of the ’70s. But Moore isn’t given enough to play, and the film’s most memorable tune is actually Ravel’s “Bolero,” which packed enough punch to instigate a future Derek movie. At his best at the keyboard, George unfortunately impresses not his wife nor his fantasy girl but a bartender. Strangely enough, the most memorable song in the film, “I Have an Ear for Love,” is not played by George but a kooky pastor. That type of composing by Mancini is far more difficult and dubious than anything demanded of George Webber — intentionally creating a song that is so bad, it’s funny. (“Ear for Love” nevertheless makes the soundtrack.)

What Moore saves is the slapstick. “10” is occasionally funny. There are witty lines throughout, mixed with clunkers such as the car crash. “10” gets from scene to scene under circumstances that should fail most B movies but somehow pass muster here. George gets stung by a bee, knocks himself down a hill, tries to drink coffee with a numb mouth, fends off cops with slurred speech, dubiously focuses his telescope, dodges traffic in a golf cart, tries to speak Spanish to all kinds of English speakers in Mexico, and there are very annoying phone-related misunderstandings, and somehow we generally laugh. (Making George’s license plate say ASCAP is a brilliant stroke by Edwards.) Moore’s shtick is effective enough that you wish the movie would’ve taken its comedy a bit more seriously.

Most movies introduce us to a character’s everyday life, then give him or her a problem. “10” is different in that George’s everyday life is backstory; his problem is already dominating his life in the first scene. Edwards should perhaps be lauded for this risky approach. But there’s a reason few attempt it: It flops. One wonders how, with this typically essential element axed, the film runs more than two hours.

Edwards cleverly gives us subtle clues as to how George’s life is unraveling. He let his driver’s license lapse. He stopped going to the dentist. He is far more observant about his gay neighbors’ relationship than his own domestic issues. He needs to be recharged. Notably, he has not turned to drugs, an interesting decision by Edwards. Such a scenario would be entirely realistic, but Edwards wants a romantic comedy, not a rehab ordeal.

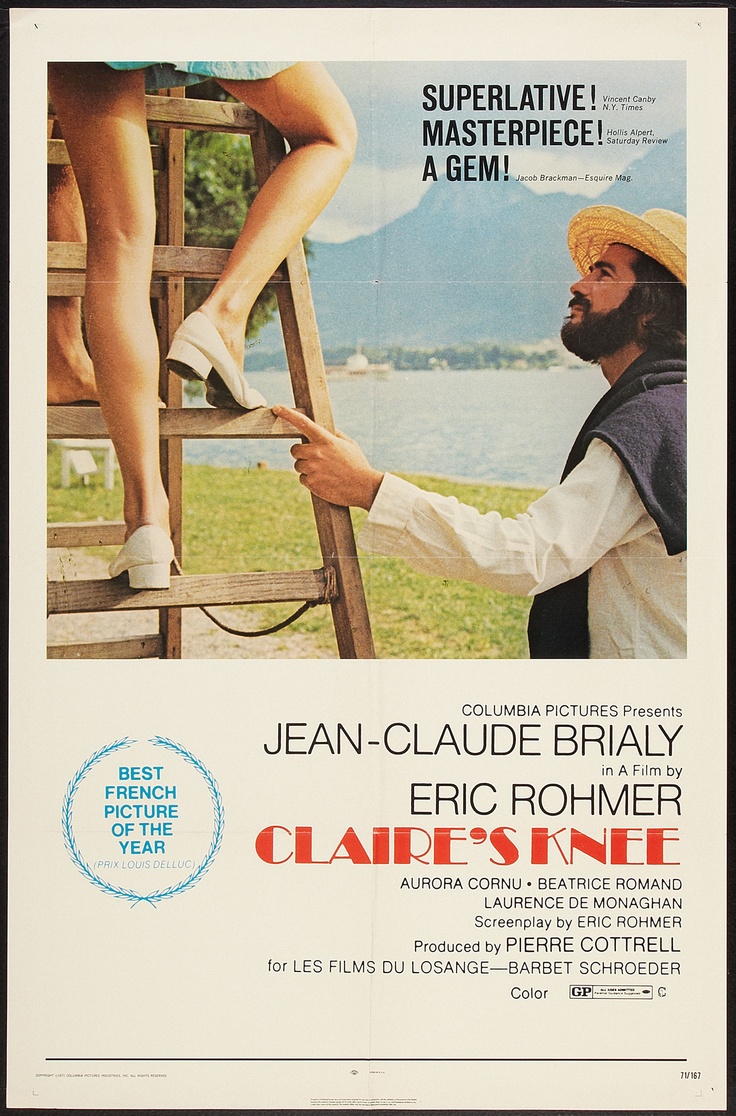

Moore can act. He gets it. He’s funny. But George is an unabashed liar, and generally, as they sometimes say in Pittsburgh, a Jagov. His pal and lyricist, Hugh, chalks it up to “male menopause,” a term associated with the film. Hugh also asserts that George is “exceedingly generous,” a trait never depicted in the film (and evidence of the value of a proper introduction). George’s conscience is somewhere below that of Jérôme in Éric Rohmer’s “Claire’s Knee” (1970). Nobody identifies the problem better than the Post’s Arnold did in 1979: “Ultimately, George is a contemptible character” who is let “off the hook morally” by Edwards, Arnold writes.

Edwards’ choice of locations is thoroughly undercooked. When a movie plot is based in Hollywood, you can put characters in all sorts of interesting locations. That works with the pool parties. But where are the celebs whom someone such as George would certainly hang out with? George spends ample time at a church, a dentist’s office and a cafe, as if this were Detroit. There’s something about his home, especially his bedroom, that feels tiny for a person of this stature. When these wealthy characters need an escape, they go all the way to ... Mexico.

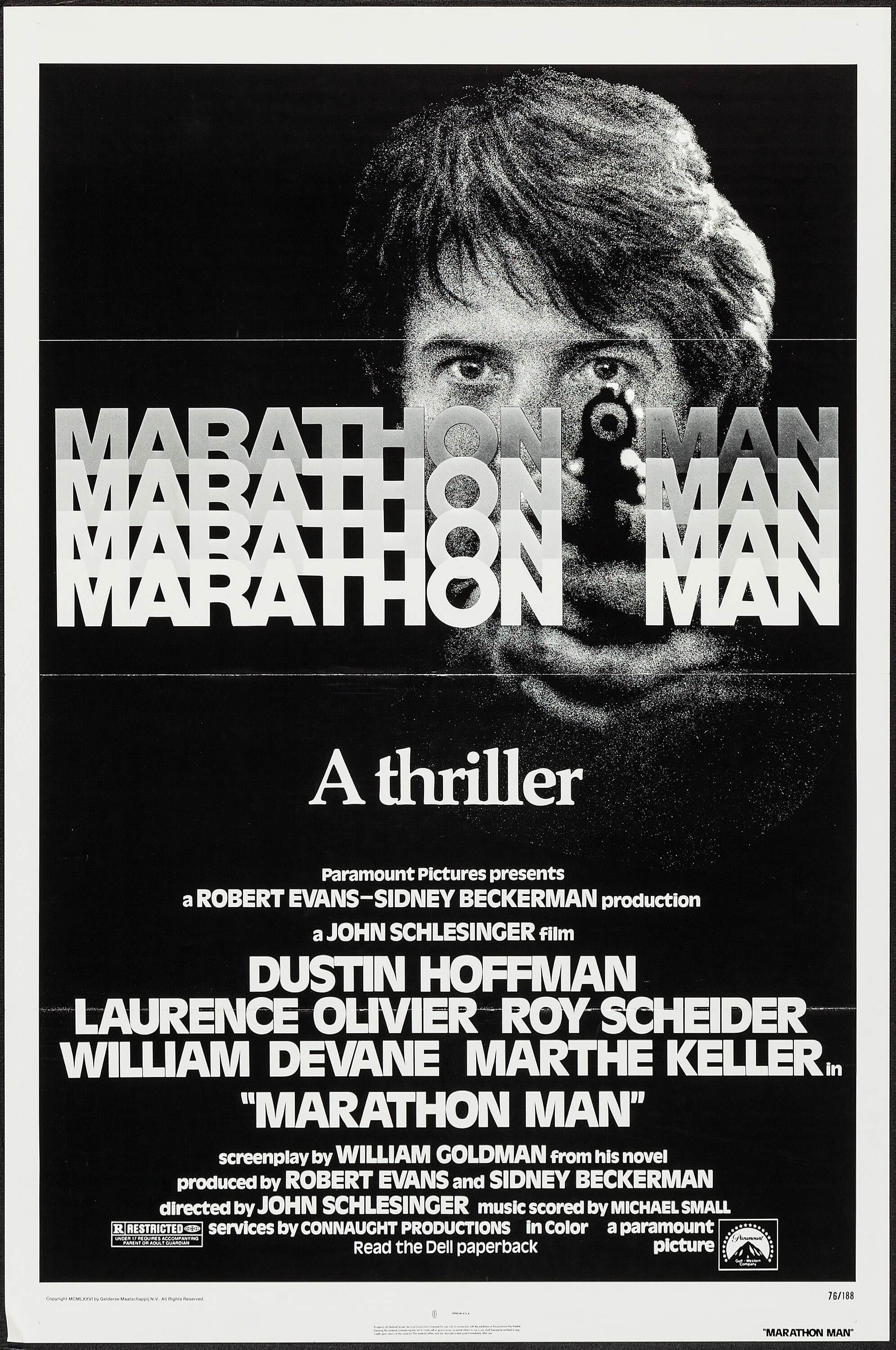

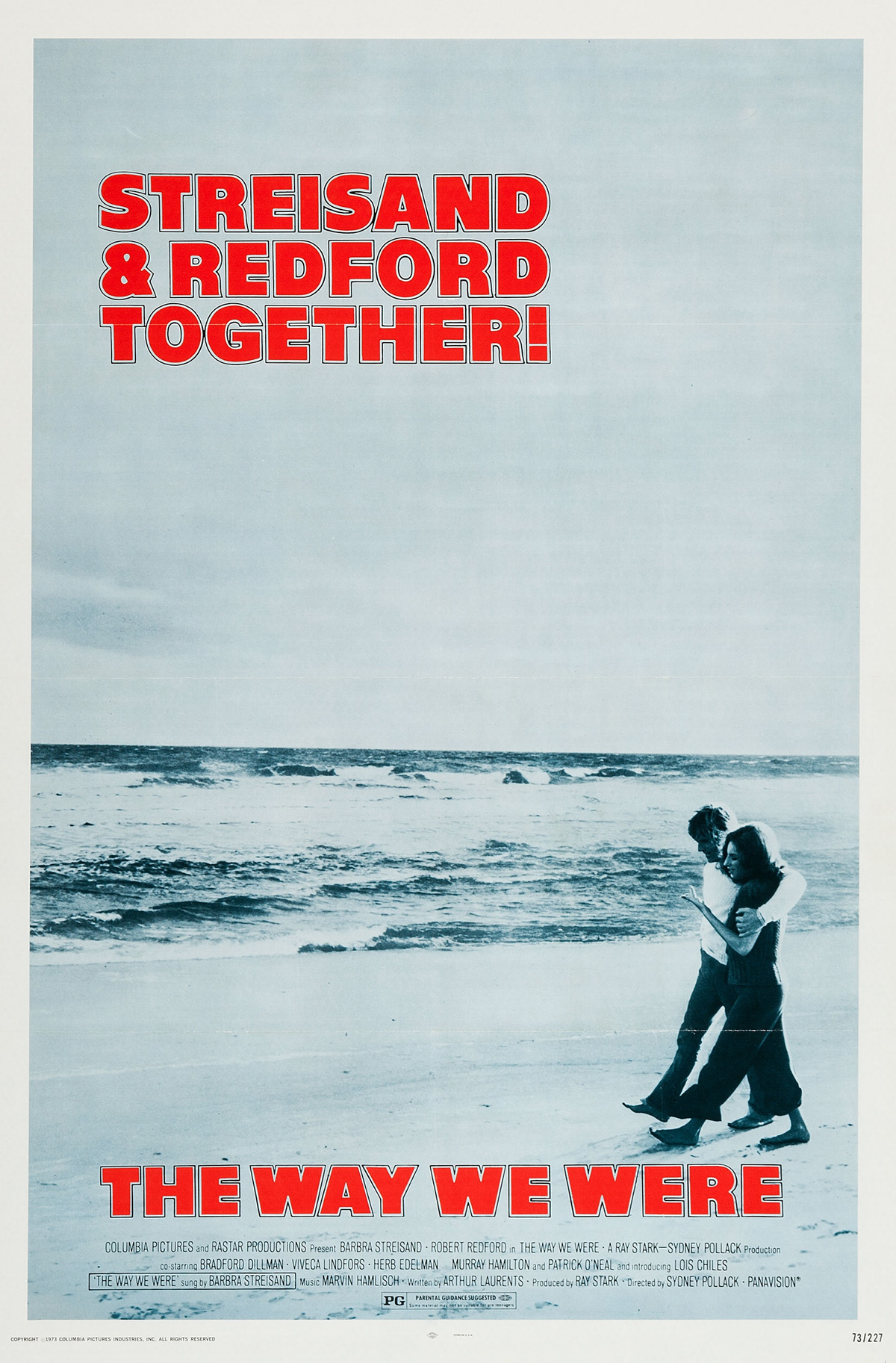

For its moral forgiveness, “10” bears parallels with another ’70s hit dealing with Southern California sexual liberation, “Shampoo.” But “10” enjoys delving into fantasy, which gave it considerable box-office loft and without which, it would be unwatchable. For many people, ramming into a police car, splitting with your significant other and nearly violating a young couple’s marriage on Day 2 or 3 would be big problems, but, as was evident in “The Way We Were,” when you’ve got a Hollywood gig and a Hollywood home, a family breakup and legal problems are mere annoyances, almost even entertaining diversions. (As in “The Player,” the cops in these parts seem to take pleasure in dealing with celebrities.) George sees a pretty girl and consults a therapist. George hits a police car, and as the officer puts it, “I think you’re, uh, gonna need a lawyer to help you with this one,” which for George is no big deal whatsoever. George is compelled to fly out of the country on a moment’s notice; no problem. (“10” will also barely echo “Marathon Man,” for its dental pain, although this time, the drill is less scary than the obnoxious but cute hygienist.)

But that’s small potatoes. Even if Moore had blown away the Oscars with a legendary role (the only Oscar nominations for “10” were for musical compositions by Henry Mancini and Robert Wells), it wouldn’t approach the pop culture explosion of Bo Derek.

According to accounts, Derek wowed Edwards with her presence and wasn’t chosen for her semi-parallel legendary backstory. In high school five to six years earlier, she caught the eye of John Derek, 30 years older, while he was married to Linda Evans, and by 16, Mary Cathleen Collins was well on her way to becoming “Bo” and had already experienced more life than most 80-year-olds. That John Derek had already chosen her for a real-life role apparently didn’t weigh on Edwards’ decision to have George Webber do the same. Author Sam Wasson says one look at Bo brought Edwards to a “skidding halt.” But pop culture is relentlessly fickle. Other filmmakers would attempt the same magic with Bo and only skidded, never got remotely close. That is the beautiful randomness of life, that Bo’s greatest scene is worth, on many levels, as much as Meryl Streep’s top 10 combined.

(Likely the second-most-famous beach scene is from a film that emerged two years later. It’s not about a girl, though, in “Chariots of Fire,” but Vangelis’ theme music that secured a best picture Oscar.)

Surely a critical question for Edwards as well as the Dereks was whether Bo should appear nude in “10.” Europeans have been far more comfortable with this concept than Americans. Bergman included glimpses of nudity in the 1950s. Antonioni photographed Vanessa Redgrave in “Blow-Up.” In “Chinatown,” there is a side glimpse of Faye Dunaway getting out of bed, no more. Take a look at the list of best actress Oscar winners, and you won’t find many known for nude scenes. Despite the smashing of certain taboos in the late ’60s, American film culture has remained remarkably consistent on the subject. Female movie stars will only be shown in the dark, and/or from the backside or side angles, and/or for perhaps fractions of a second. For scenes requiring a lengthy look, obscure models are hired. “10” will show Dudley Moore peeping at naked women you’ve never heard of in broad daylight before conversing with Derek partly covered in blankets in a dimly lit room.

Edwards’ bookend to the Bo Derek discovery is the title of “10,” one of maybe a dozen on the short list of Greatest Movie Title Ever. It’s unknown whether Edwards or someone else wrote it — or whether they might’ve been inspired by some other uses of the term “10.” A few years before the movie, the most prominent 10’s in the world (actually “10.0” would be more accurate) were those earned by the magnificent Nadia Comăneci, who incredibly rained seven of them at the 1976 Montreal Summer Games, the first time an Olympic gymnast had achieved perfection even once.

Edwards’ work is not about athleticism, but attraction, and in his movie, that number became the description of the ultimate fantasy category, the most unattainable woman. Incredibly, Edwards nearly botched it. He introduces the term during George’s analysis session, when the psychologist asks for George’s scorecard on Jenny, “on a scale from, uh, 1 to 10.” George’s answer is “11,” at odds with the perfect title. No one cared. Sometimes people will say “11” or “15” for emphasis, but “10” is the standard, then and now.

Since the creation of Hollywood, there is considerable debate as to whether movies constitute art or entertainment. Sometimes movies take society to places it hasn’t been. “10” strews around underwhelming slapstick, can’t count and nearly buries its crown jewel. Yet “10” soared into 1979’s top 10 and rained cash. Its budget, according to an unattributed Wikipedia entry, was a mere $7 million. It grossed $75 million; its pop culture return, parabolic.

3 stars

(October 2018)

“10” (1979)

Starring: Dudley Moore

as George Webber ♦

Julie Andrews

as Samantha Taylor ♦

(Introducing) Bo Derek

as Jenny Hanley ♦

Robert Webber

as Hugh ♦

Dee Wallace

as Mary Lewis ♦

Sam Jones

as David Hanley ♦

Brian Dennehy

as Donald ♦

Max Showalter

as Reverend ♦

Rad Daly

as Josh Taylor ♦

Nedra Volz

as Mrs. Kissell ♦

James Noble

as Dr. Miles ♦

Virginia Kiser

as Ethel Miles ♦

John Hawker

as Covington ♦

Deborah Rush

as Dental assistant ♦

Don Calfa

as Neighbor ♦

Walter George Alton

as Larry ♦

John Hancock

as Dr. Croce ♦

Lorry Goldman

as Bernie Kaufman ♦

Arthur Rosenberg

as Pharmacist ♦

Mari Gorman

as Coffee Shop Waitress ♦

Marcy Hanson

as Magazine Reader in Coffee Shop ♦

Senilo Tanney ♦

Kitty De Carlo ♦

Bill Lucking

as Policeman ♦

Owen Sullivan ♦

Debbie White ♦

Laurence Carr ♦

Camila Ashland ♦

Burke Byrnes ♦

Doug Sheehan

as Police Officer ♦

Victor J. Lopez ♦

Jon Linton ♦

John Chappell

as Man on beach ♦

Art Kassul

as Large man ♦

Julie Alter

as Party Guest ♦

Adam Anderson

as Party Guest ♦

Jeannetta Arnette

as Party Guest ♦

Adrian Aron

as Party Guest ♦

Gail Bowman

as Party Guest ♦

Sheila Cassidy

as Party Guest ♦

Michael Champion

as Party Guest ♦

Gregory Chase

as Party Guest ♦

Lisa Chess

as Party Guest ♦

Ellen Clark

as Party Guest ♦

S. Colombatto

as Party Guest ♦

Antonia Ellis

as Party Guest ♦

Lynn Farrell

as Party Guest ♦

Vivian Farren

as Party Guest ♦

Yolanda Galardo

as Party Guest ♦

Sharri Zak

as Party Guest

Directed by: Blake Edwards

Written by: Blake Edwards

Producer: Blake Edwards

Producer: Tony Adams

Original music: Henry Mancini

Songs: Robert Wells (lyrics); Henry Mancini (music)

Cinematography: Frank Stanley

Editor: Ralph E. Winters

Production design: Rodger Maus

Set decoration: Reg Allen, Jack Stephens

Casting: Lynn Stalmaster

Costumes: Patricia Edwards

Makeup and hair: John Isaacs (Julie Andrews hair), Mary Keats, Ben Nye Jr., Bron Roylance

Production manager: Chuck Murray

Stunt coordinator: Dick Crockett

Stunts: Jerry Summers, Hill Farnsworth, Richard R. Drown

Dedicated with Love and Respect to: Dick Crockett