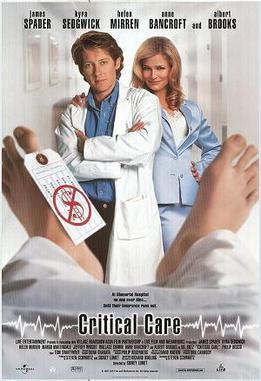

In ‘Critical Care,’ a hospital gets far better returns on the comatose than the film does

The medical industry is forever controversial. No one can deny that healing fellow human beings is very much an “industry,” one subject to greed, manipulation and ... satire.

“Critical Care,” the 1997 film about end-of-life decisions directed by Sidney Lumet, based on the first novel of Richard Dooling, takes a shot at all three. There aren’t many obvious visuals in the depiction of health insurance, but “Critical” gives it a try. It bites off more than it can diagnose and is probably best suited as a play. In its details, it appears to be a mockery of HMO judgments, but its heart is with its conclusions: that the system for several reasons conspires to keep people “alive” for much longer than they should be.

“Critical Care” was released in the heyday of Jack Kevorkian, but the behavior depicted in the film would fall only under a category called passive euthanasia. That doesn’t sound like a barrel of laughs, but this is parody. Steven Schwartz’s screenplay wants viewers to chuckle at the characters, not mourn them. There are three patients facing a very bleak outlook. Bed One and Bed Five may or may not be able to express their opinions, so others will have to make the call on their behalf. Bed Two strongly indicates he does not want to live, but we hear he’s being kept alive by the loving demands of his relatives.

“Critical Care” deals itself several obstacles. Showing brain-dead or brain-compromised humans full of tubes isn’t enough to carry a feature film. Characters are required to make ridiculously lengthy speeches about why they’re doing what they’re doing. The cameras hardly ever get out of the hospital. The film does, however, find its way to an uncomfortable and significant truth — that death is stamped with some kind of price tag.

The necessity of “Critical Care” is to turn James Spader’s freshly minted M.D. from a mechanic into a doctor. Bored out of his mind, he is assigned to assure that a group of patients in vegetative states will remain that way for no other reason than for the hospital to continue to collect from the insurance companies. Why does he seem OK with this profession? It attracts girls, whether fellow staffers or relatives of his patients; they may have little use for him but they all respect those two letters after his name. By the end, he will confidently declare himself a physician. His characterization is not all that different from the underachieving lawyer Daniel Kaffee in “A Few Good Men” (why do Tom Cruise films so often serve as analogies?).

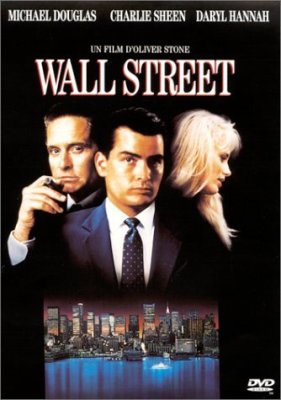

Spader appeared a decade earlier in “Wall Street,” as a successful and diligent young lawyer easily corrupted by the prospect of a windfall. He is not the protagonist of that film, and in “Critical Care,” at the time we meet him, he is already a sellout, not advancing the cause of humanity but punching the clock until he secures a better gig. Like many playboy characters, his vices are limited to skirt-chasing, not alcohol or drugs. He curiously is costumed in a Chicago Bulls jacket. Is that a sign he sides with the winners (remember, this is a 1997 film) or doesn’t take himself too seriously? The thing is, in “Wall Street,” we know Bud Fox. By the end of “Critical Care,” can you even recall Spader’s character’s name? (That would be Dr. Werner Ernst.)

Unlike with Bud Fox, Spader’s family, socio-economic and even educational background are left out of this one. He mumbles that he grew up a science nerd. That’s not really believable, you’ll have to take his word for it, but that probably explains why he was hired, that he cares more about technology and machinery than the human spirit. Did he go to an elite school, or bottom of the barrel? In the opening scenes, the chief nurse, played by Helen Mirren, mocks him for ogling a woman and suggests he is making up for the “hour or two you wasted on patients today.” No question, he’s capable of much more. From time to time, he does critique what he considers dubious decisions and dubious people in authority. But any convictions are cast aside by the opportunity to earn a promotion from Dr. Hofstader, who asserts, “Seeing patients is a waste of a doctor’s time. We’re trying to correct that problem.”

Some say Spader should’ve been cast as Bud Fox in “Wall Street.” His range may be limited, but indeed, he proves here he can carry a film, even among a highly credentialed cast including Helen Mirren, Albert Brooks, Edward Herrmann, Wallace Shawn and Anne Bancroft. There is something about him that can’t be fully trusted, yet it feels necessary to have him on your side.

Hospitals are great sources of drama, a sub-genre of probably dozens of compelling TV shows. The facility in “Critical Care” seems not a modern hospital but something beyond that. We see patients in pod-like rooms, sitting up on state-of-the-art air mattresses. It’s a setting that appears lifted from sci-fi material (both serious and spoof), a space-age type of bright-white environment. The opening scenes mistakenly suggest the film might be set in the future; it would be better to show Spader driving to work in a contemporary car first. It is quickly established that, unlike the TV dramas, we’re not going to get much out of these patients, so we have to wait to hear from their relatives.

Around the 10-minute mark, we get the problem. Kyra Sedgwick, playing grieving daughter Felicia Potter, wants her father’s suffering to end. That would seem possible, except she has to explain to Ernst that her half-sister, Connie Potter, has a different idea about the care their dad should get. At first, we see what may be a sincere disagreement as to whether to pull the plug. Connie is played by Margo Martindale, who ... in a remarkable coincidence ... would years later play the selfish mother of Maggie Fitzgerald in “Million Dollar Baby.” (There is Hollywood typecasting, and then there is hyper-Hollywood typecasting.) After the details of the daughters’ underlying financial interests are revealed, it seems each is attempting to maybe do the right thing for exactly the wrong reason. That reality is cemented in Connie’s unnecessary closing line, which Roger Ebert called “an inappropriate clinker.”

Felicia, though, is even worse, prostituting herself to gain the upper hand. She tells Werner, “You are the first doctor I’ve met who seems human,” highly effective subtext indicating both Werner’s personal development and her own sales pitch. Their bedroom scene is awkward but concludes with Lumet’s best depiction, the impressive camera rotation into the closet shelf. That work is undermined later by someone’s idea that Felicia needs to actually tell Werner, “I’m blackmailing you. ... I want you to kill my father ... Just kill my father, or I’ll end your medical career.” One step forward, one step back.

The clever tug-of-war of “Critical Care” is certainly highly improbable, but real-life situations have shown that assessing a declining person’s mental fitness is, at best, far more complicated than this movie allows. Sumner Redstone, the movie mogul with financial interests far, far beyond $10 million, experienced health deterioration in the mid-2010s, and courts had to decide chairmanships of his companies as well as control of his voting stock. Somewhere in the middle was messy litigation with a former live-in girlfriend, who claimed he was not of sound mind when he kicked her out and, yes, canceled her right to make health care decisions for him. (See how many layers can happen here?) Redstone is still alive. Perhaps his estate is already settled; perhaps not.

While Spader holds his own, Albert Brooks, as the aging drunkard Dr. Butz, threatens to steal the show and possibly could if given more than a one-note routine. He sincerely wonders, “What’s wrong with Bed Five? He’s all paid up!” The apparent kingpin of this room-and-board production of a hospital, he implies that it’s the other guys who are the problem, the ones dumping the uninsured patients at his doorstep. Brooks’ timing and demeanor are reminiscent of a lovable uncle, even if he’s the source of massive frustration. This is a satire, and he’s the only character who’s funny. He barely knows what planet he’s on, but he’s somehow razor-sharp at discerning the insurance value of every patient, hence, he’s considered an asset.

The serious reflections in “Critical Care” are supplied by Helen Mirren’s Stella, the top nurse on the floor who sees everything that Werner does but actually enjoys interacting with patients. She appreciates hearing the pain and torment and eventually will deem herself qualified to make ultimate judgments, either because 1) she believes she understands these patients better than anyone else, or 2) rather flimsily, she knows the devastation of serious illness (which she illustrates in a completely inappropriate and/or unethical demonstration, a foreshadow of the ending) and why some would choose not to carry on. In “ER,” there’s an episode where top nurse Julianna Margulies entertains going to med school, only to wrongly disagree with a doctor and realize it’s not as simple as it looks. In “Critical Care,” Stella on multiple levels acts beyond her pay grade, something society shouldn’t really accept.

Her primary subject is Rafael, or “Bed Two,” an unusually young patient for this environment. His commentary on why he’s here and what he deserves are in fact something out of Albert Brooks’ “Defending Your Life” (that six degrees thing really makes a lot of sense). Rafael is mentally competent, but Stella explains that his family is making the decisions on his care, and out of what they see as love. Rafael responds, “F--- em. What do they know about it. Wait till their time comes.”

Rafael’s visions featuring Wallace Shawn hint at how Dooling seems to envision a happy outcome: that there is an afterlife, something beyond these beds, so deaths of people in this condition are not something to mourn.

The bad guys include Hofstader, the lab king who believes computer models (in 1997, before Google and AI) are “identical with any patient,” and his chief disciple, Poindexter, a rival of Werner who tells him, “There is no longer any condition that is truly terminal. Just patients we choose not to maintain.” Also there is Wilson, the hospital lawyer who is preoccupied with watching the stock market ticker on his TV.

Another lawyer, the outside counsel Robert Payne, is played by Edward Herrmann, he of the beautiful, reassuring voice who cinematically earned his legal bona fides a couple decades earlier as a member of Ford’s study group in “The Paper Chase.” That group didn’t have any courses on end-of-life care, but Payne looks to be up to the challenge. His character, who is curiously neutral, probably exists to show the hospital’s disinterest in its own cases. It might be that Schwartz and Lumet just wanted to beef up the legal dialogue. Dooling, according to his website, is in fact a lawyer and not an M.D. (unlike, for example, Michael Crichton, who might have had a different approach to this material) and writes, “One of my hobbies is computer programming.”

Maybe the most astonishing detail of “Critical Care” is not even in the film. According to IMDB and boxofficemojo.com, it grossed far less than the Conner sisters — a mere $221,000. That kind of number seems hardly enough to cover the fee of Lumet, Spader, or any of its impressive contingent of stars, who hopefully didn’t negotiate a percentage of the gross. The movie reportedly was shown in 34 theaters. By contrast, “Men in Black” was shown in 3,180. With this kind of return on a reported budget of $12,000,000, the producers of “Critical Care” — Lumet and Schwartz — probably wondered if they should’ve pulled the plug.

Box office results are not a fair evaluation of a film’s worth and won’t be used to judge “Critical Care” here. “Hard Eight,” for example, an excellent film, finished just barely ahead of “Critical Care” in receipts that year. But the box office is, however, evidence that Dooling’s message fell on an unresponsive public that either doesn’t want to contemplate this subject or just doesn’t find it very interesting.

In Hollywood, what goes around, comes around. Sidney Lumet directed at least 40 feature films, according to the Internet Movie Database. “Critical Care” was one of his last. Was he inspired? He helmed “The Verdict,” in which the goal is to procure enough money to provide ... ongoing care for a comatose woman.

“Critical Care” is a first novel, and for cinematic purposes, it could’ve been sharper. It presents a shaky certainty of only a couple things, that 1) “brain-dead” means “dead” and 2) any brain-dead person capable of responding wants the machines off. The movie would have us believe that only the people smart enough or wealthy enough to buy insurance are the ones who get treated, except, on the other hand, they’ll be overtreated, robbed of peace or dignity, used as cash cows for dorks like Poindexter.

Reducing or eliminating treatment is not really that controversial. Every day, challenged patients and their physicians must make decisions on how much care might be detrimental, either to quality of life or dignity. The controversy in “Critical Care” is about who’s making that call. The movie wants the villain to be the HMOs. It indicts something far more distressing: our next of kin.

2.5 stars

(April 2020)

“Critical Care” (1997)

Starring

James Spader

as Dr. Werner Ernst ♦

Kyra Sedgwick

as Felicia Potter ♦

Helen Mirren

as Stella ♦

Anne Bancroft

as Nun ♦

Albert Brooks

as Dr. Butz ♦

Jeffrey Wright

as Bed Two ♦

Margo Martindale

as Connie Potter ♦

Wallace Shawn

as Furnaceman ♦

Philip Bosco

as Dr. Hofstader ♦

Colm Feore

as Wilson ♦

Edward Herrmann

as Robert Payne ♦

James Lally

as Poindexter ♦

Harvey Atkin

as Judge Fatale ♦

Al Waxman

as Sheldon Hatchett ♦

Hamish McEwan

as Hansen ♦

Jackie Richardson

as Mrs. Steckler ♦

Barbara Eve Harris

as E.R. Nurse ♦

Conrad Coates

as Dr. Miller ♦

Bruno Dressler

as Potter ♦

Caroline Nielsen

as Luscious Nurse ♦

Gladys O’Connor

as Bed One ♦

Kay Hawtrey

as Dr. Butz’s Secretary ♦

Don Carmody

as Maitre d’ ♦

Kim Roberts

as Intern #1 ♦

Naomi Blicker

as Intern #2 ♦

Merwin Mondesir

as Head Injury ♦

Bruce Hemmings

as Orderly ♦

Paul Brown

as Insurance Man ♦

Michael Colton

as The Boy

Directed by: Sidney Lumet

Written by: Richard Dooling (novel)

Written by: Steven Schwartz (screenplay)

Producer: Sidney Lumet

Producer: Steven Schwartz

Executive producer: Don Carmody

Cinematography: David Watkin

Editing: Tom Swartwout

Casting: Avy Kaufman

Production design: Philip Rosenberg

Art direction: Dennis Davenport

Set decoration: Enrico Campana, Carolyn Cartwright

Costume designs: Dona Granata

Makeup: Rick Baker, Kazu Hiro, Patricia Green, Sylvia Nava, Jennifer O’Halloran, Evan Penny, Jay McClennen

Unit production manager: Joyce Kozy King

Post-production supervisor: Lilith Jacobs

Executive in charge of production: Yalda Tehranian

Stunts: Dan Belley