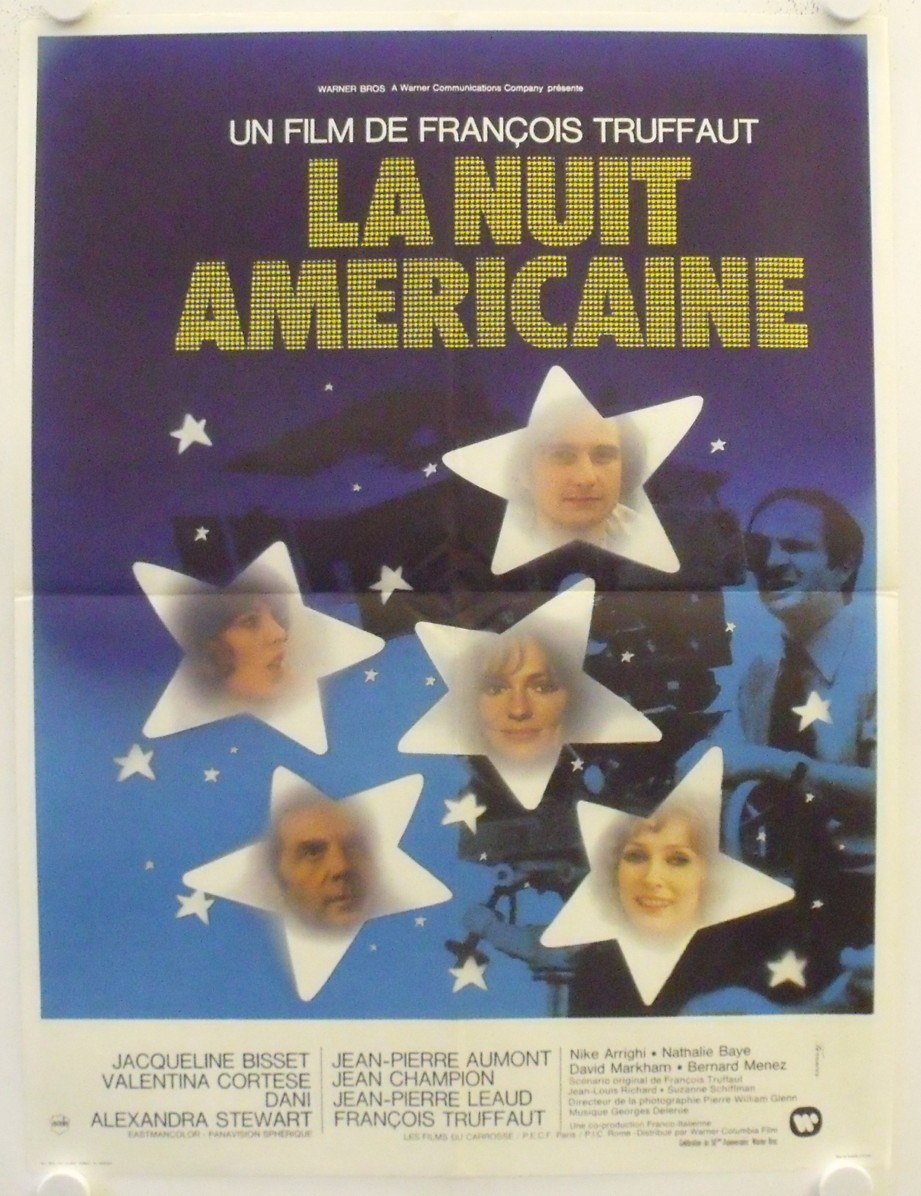

‘Day for Night’ — When sex threatens to ruin a bad movie

There is nothing complicated about “Day for Night.” Shortly into the first scene, we learn that we’re watching a movie within a movie. The former is obviously not very good. The latter? You better give it a chance.

“Day for Night” is an expression of the forces of time, space, adrenaline. Crammed into two months of moviemaking, those elements are remarkably visual, emotional and, most importantly to American audiences, universal.

Hollywood might be highly global, but there is something native about films that speaks to their natural audiences and generally not as well to others. When the dollar and euro trade at 1:1, it’s called parity; “Day for Night” is a rare movie in a foreign language that trades at parity, likely François Truffaut’s most popular film among Americans.

Plenty of films have tackled Hollywood. That’s a place and a business, not really an art form. “Day for Night” asserts that no matter where or how it happens, moviemaking is not a job but a lifestyle, one in which there is never a shortage of vanity or ego.

Some of that may even extend to its humble maestro. Truffaut, as the director Ferrand, quietly puts himself at the center of the movie — the real movie, not “Meet Pamela.” Ferrand is the hero. The meager drama here is whether he can wrap the film. We learn early that he is a veteran director handed a manageable but difficult situation. It gets worse. His ingenuity and sensitivities are put to the test. Many of the crises are frivolous. That’s moviemaking.

As Ferrand, Truffaut is Richie Cunningham, Brandon Walsh, Archie Andrews. Directors may be all kinds of styles. The perfectionists would walk out of “Meet Pamela.” The bohemians would never finish it. One of the director’s biggest jobs is dealing with difficult people. Observe Ferrand’s demeanor. The biggest beef against him would be that he is too indulgent of flakes, has not enough of an edge, settles for mediocrity. On the other hand, he makes exceptional rapid-fire judgments, is adept enough to satisfy jittery producers, and is just as comfortable among megastars as camera operators. The “Meet Pamela” cast and crew will depart not gushing about him but looking forward to the opportunity to work with him again. If the actors and crew around him were polled, they would say his greatest strength is that he listens to them.

His nemesis is not the producer nor the movie stars. Cleverly, it is Liliane, the script girl trainee played by Dani, whose roots were in the French pop music scene. Liliane, while borderline insufferable, is a crucial personality, the anti-Truffaut. She can probably do this job, but she doesn’t get it. Movies and movie stars mean little to her. She’d find just as much, if not more, excitement at an IBM golf outing. She gets a job for which many would risk death only because her boyfriend is one of the stars, and her conclusion is to walk. She cannot defeat Ferrand, but she can very subtly deflate what his world is all about.

There are about five major figures in “Day for Night” playing themselves, really, albeit with character names: Truffaut, Hollywood veteran Jean-Pierre Aumont, Valentina Cortese, Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” prodigy Jean-Pierre Léaud and of course, Jacqueline Bisset. They’ve all seen this movie before and, while there’s a risk the results could be eye-rolling, all thrive on the caricatures, a bit like Cary Grant’s self-references in “North by Northwest.”

We care not what they do at their homes but how they handle this professional tinderbox. The brotherhood and sisterhood is real. It may only be an inch deep, but it’s not phony, a credit to Truffaut’s vision. The lives of the cast and crew will intersect at intimate levels, and then it will be on to the next project; some will meet again months or years later. Moviemaking is a true team effort; seemingly irrelevant crew members (conveniently, they tend to have their names mentioned in dialogue so we easily can keep track of them) can uncork some of the biggest problems. “Day for Night” is beset not with tragedy but what we today would call “First World problems.” Is there really any drama here? Most of the characters are obviously well paid, with considerable filmmaking cred, and the dubious “Meet Pamela” production won’t make or break anyone’s career; it’s just another couple months at the office.

Reviewing “Day for Night,” Pauline Kael complained, “The picture has no center and not much spirit.” Drama only exists here because moviemaking, as Truffaut shows, is fascinating. One of the things we learn from this film (if we somehow didn’t know it already) is that moviemaking tends to be done by attractive people. It’s also enormously unpredictable. The biggest risk, according to this film, is that an actor will fail, quit, or become incapacitated. Lesser risks include financiers shortening the timetable, and basic mechanical failures. We learn several reasons why movie scenes need to be re-shot. There could be a power failure at a lab, an actress is not-so-secretly pregnant, a cat won't perform, a bus can be a couple of seconds off in the timing of a complex scene.

There are some very important characters never seen in “Day for Night.” Those would be spouses. The lack thereof opens the floodgates to something else that’s exciting and consequential: sexual liberty. In “Day for Night,” it’s usually whoever gets to a person last in the evening gets to share the bed. Notice Truffaut’s moral equivocating here. Virtually all of the characters are unmarried or unattached, and the only one committing serious adultery is compelled to point out that her husband did the same. The implication is that the environment of a film project has an effect on people in a way that the jungles of Vietnam affect the distinguished soldiers of “Apocalypse Now.” The judgment of “Day for Night” is that in this setting, sex happens, means little, and must be forgiven.

But actually, it does mean something. Forget the lab failures and American deadlines. Sex is the biggest threat to “Meet Pamela.” Notice only one character drinks on the set to wary eyes, but the crew is nearly oblivious to the risk of random hookups. The risk is, important people might quit over them. We know that historically, directors are as prone to this as the cast and crew, but in “Meet Pamela,” Ferrand is possibly the only character who sleeps alone. (Truffaut does not wear a ring.)

The only tryst that borders on exciting is when the gorgeous script girl Joelle (Nathalie Baye, whose more approachable beauty can match Bisset stride for stride) needs to change clothes in the woods and makes an offer to the fortunate but unassuming prop man with her, Bernard (Bernard Menez), who can’t seem to believe his good fortune and can’t help but wonder, what’s the catch?

There is a decent undercurrent, but the gossip among the “Meet Pamela” production seems understated, as do concerns about salaries and number of scenes and lines.

But artistic license is necessary. In his four-star, original 1973 review of the film, Roger Ebert declares, “A movie set is one of the most boring places on earth most of the time,” and he is surely correct, which is why Truffaut whips us through this production at impressive lightning speed. Even having a simple one-to-one conversation is difficult; Ferrand is interrupted constantly with minutiae and irrelevancies, people sometimes talking over each other Altman-style. These not only keep the whirlwind going, they allow another beautifully understated element, Ferrand’s authentic, rapid-fire opinions on the project. He evaluates wigs and fake guns and mulls whether painting a crashing car blue is worth $650, or whether to leave it white, or whether to use someone else’s blue car, the latter being the car of his assistant, Jean-Francois, but “maybe he won’t mind.”

One of the best scenes involves Ferrand and the chief operator, Walter (Walter Bal), looking over pictures of Bisset’s Julie Baker and discussing her features and issues. Amateurs love to make their own assessments, but this is an elite evaluation, like listening to a quarterback privately explain why he might audible. “Lovely eyes ... good face, nice shape.” Notice that they linger on the first picture. And how is she to work with? They know little more than the tabloids. She had a “minor depression,” but, “Now she’s married to her doctor — she must be fine now.”

While the production is egalitarian, we also notice that anything to do with Julie Baker merits the royal treatment. She gets a hero’s welcome and airport press conference. Her husband interrupts a scene; he’s given a front-row seat. Julie’s drama like that of the rest of the film is heavily telegraphed. Ferrand discusses her breakdown not only with Walter but the producer, Bertrand (Jean Champion), who notes the insurance risk of the star’s emotional problems, and if it happens this time, “we’ll be in hot water.”

Alas, purported fragility is the only thing about Julie that is not authentically Bisset. In a 1982 interview, Roger Ebert notes that Bisset is not only highly paid but highly productive, and there is “no denying” her beauty and wide-set eyes. But Oscar-type acclaim is absent. She’s perfect for “Meet Pamela,” because as Ebert wrote, “Few actresses have been busier in the last 17 years to less avail.”

“Day for Night” is only bogged down when Truffaut opts to give nine frustrating minutes to the inability of Séverine, the Old Hollywood character played by Valentina Cortese, to finish a simple scene. She is unable to open the correct door, although doing so would appear to be awkward. This happens presumably because it’s necessary to show at least one actor (besides a cat) who can’t perform; the others are consistently strong. Why does Séverine have such trouble? Too much booze or not enough? She wants to use Fellini-style dubbing so she doesn’t need to say the lines. Truffaut insists she must say the lines; she suggests cue cards. Truffaut likely is offering a wink at New Wave vs. Old Hollywood. After several failed attempts at opening the correct door, she complains of being confused by the presence of her makeup artist playing the maid. “In my day, acting was acting, and makeup was makeup. No wonder I’m confused!”

In a weak and unnecessary explanation, we learn from script girl Joelle that Séverine’s son is “dying of leukemia” and that “she almost turned down the film,” one of two or three examples (including Séverine’s “very stormy” affair four years ago with Alexandre) of “Day for Night” leaning on unfortunate offscreen crutches.

Somehow, Cortese was nominated for the best supporting actress Academy Award for this role and lost to Ingrid Bergman in “Murder on the Orient Express.” Perhaps empathy drove the appreciation of Cortese’s work. In her speech, Bergman said the Oscars were guilty of “wrong timing ... because last year when ‘Day and (sic) Night’ won for the best (foreign-language) picture, I couldn’t believe it that Valentina Cortese was not nominated because she gave the most beautiful performance ... after all, we have all forgotten our lines and always opened the wrong doors, and it was wonderful to see her do it so beautifully.” (Translation: I would’ve preferred not to have bested my friend for this award, and if the Oscars didn’t have these silly timing rules of the era in which nominations for best foreign film and the actors in them would sometimes occur in different years, I wouldn’t have been competing with her.) (In a 1978 interview with Dick Cavett, Bergman calls the film “Night and Day,” then “Night for Day.” Cavett agrees it is “Night for Day.”)

Jean-Pierre Aumont, the veteran stalwart of “Meet Pamela,” could be the hero, but this is Truffaut’s film. Aumont is actually at his finest during Séverine’s meltdown, the distinguished star calmly riding out the waves. A character analysis of Aumont’s Alexandre finds that unfortunately, just enough is suggested about him as to make the portrayal incomplete. Alexandre is who Ebert would call the “reliable observer” in the film, the consummate pro, beloved colleague, glowing with stature ... until we learn how even he can let the project down too (through no fault of his own).

What’s he got going on? The script girl says he’s at the airport as usual; “I bet he has personal problems.” No one’s sure if he is married; “he’s very secretive.”

Eventually, Alexandre will introduce a young adult male to his colleagues and declare he wants to “adopt” him to have someone carry on his name, but 1) Alexandre isn’t married, and 2) the young guy doesn’t have a French passport. Draw your own conclusions.

Alphonse is played by longtime Truffaut fixture and (highly productive) French New Wave legend Jean-Pierre Léaud, who curiously was just coming off a scattershot role as a director of a picture within a picture in “Last Tango in Paris.” Impulsive to the point of ADD, Alphonse wouldn’t be in the “Meet Pamela” cast except that he is an exceptional and diligent actor (though he admits, “I never read scripts”), in the rare air of stardom, and thus he must be indulged. But not to the extent of Julie Baker, and he will get less attention from Ferrand than his Hollywood counterpart. That Alphonse and Julie should connect is a reach, but this is a movie set. Notice that when Alphonse has decided to bolt, he uses an intermediary — calling Julie and asking her to tell Ferrand for him, which might be either a cry for help or a clever approach on Alphonse’s part.

Liliane summarizes Alphonse beautifully as Julie Baker frowns: “He needs a wife, a mistress, a nanny, a nurse, a sister … I can’t play all of those roles.” Oddly enough, the same could be said for Julie, who needs a physician more than a husband.

When Liliane leaves, it prompts one of the film’s most memorable lines, from a stunned and disheartened Joelle, who tells Julie Baker, “I’d drop a guy for a film. I’d never drop a film for a guy!”

That is truth. But there are others, such as Sofia Coppola’s spectacular collection of “Lost in Translation,” “Somewhere” and “The Bling Ring.” Each is a separate project. Together, they paint a most uninspiring portrait of movie stars and their lifestyle that Joelle would find remarkably foreign.

In black and white, “Day for Night” might be little more than farce. But this is Nice. Truffaut sprinkles this film with spectacular early 1970s color that enriches the circus atmosphere. Observe the photo below from the opening scene: a small patch of green grass, a towering red crane for elevating the camera, red and yellow awnings, shades of green, yellow and gray walls, about four dozen extras in bright clothing. Later there are the subtle touches — a yellow bedroom clock, plaid chairs in the screening room, dark blue from a window, the uniform of makeup artist Odile.

More than the color, Truffaut enjoys revealing some minor secrets. How snow is made for a scene shot in the summer. How characters can appear to be in two buildings when only one building exists. How cast and crew matter-of-factly assume risks on elevated cranes and sets. Cinematographer Pierre-William Glenn depicts these tricks while gliding effortlessly between stunning close-ups and bird’s-eye views. We can see that making a film about a tragic romance is as technical as it is emotional.

The film’s signature quote comes early from Ferrand’s narration: “Shooting a movie is like a stagecoach ride in the Old West. At first you hope for a nice trip. Soon you just hope to reach your destination.”

Coincidentally, Ferrand delivers one of the funniest lines of the ’70s, translated as: “An actress who won’t appear in a bathing suit is ludicrous!”

“Meet Pamela” has to be a bomb. Were it actually an appealing plot, it would be wasted and counterproductive, and “Day for Night” would be not so ripe for comedy. In the beginning, and again in the middle of the film, characters explain what “Meet Pamela” is about with a seriousness that suggests this is the best acting they’ll do. (In another nod to simplicity, Ferrand and Julie will also explain what the term “day for night” means. In French, it is called “la nuit américaine.”) Bisset, a flourishing siren in some scenes, is inexplicably given a housewife wig in others. Because we’re told often enough, we know what happens in “Meet Pamela,” and we don’t have to keep track of its scenes, though they seem to be filmed largely in order; “Day for Night” is not as ambitious as “Pulp Fiction.” Someone asks Julie at her press conference if anyone cares about a plot like this. Her answer is that she likes the script enough to do it, and when that happens, she expects audiences to like it too. (Somehow, no one at this movie star’s press conference knows who her husband is or that he is seated in the middle of all of them.)

Goofs seem like they might be intentional, Truffaut’s nod to the hazards of production. At one point he is shown in a flipped image, his earpiece in his right ear and hair parted on right side; late in the film he consoles Julie Baker and is briefly shown twice without the earpiece.

“Day for Night” conveys that movies are such enormous projects of moving pieces, they can’t really be guided, but at best contained. That they are less about sophisticated planning than trial and error. That efficiency, not creativity, is the key to the product and to one’s career. Truffaut laments in “Day” that he will think about more work he could have done to improve the output. There are a few notable examples of cinematic artistic indulgence, including “Citizen Kane” (well worth it) and “Heaven’s Gate” (not exactly). Were it not having fun, “Day for Night” could have a more powerful ending with a “Heaven’s Gate” type of outcome in which Truffaut’s pursuit of perfection drives the financiers into bankruptcy.

Handsome enough to be a film actor (though likely in character roles), Truffaut is among the most beloved directors largely because of his reverence for the profession. “Day for Night” does not skip a beat, at one point showing Truffaut unloading a bag of books in tribute to the world’s most famous cinematic auteurs. It likely would take the most seasoned New Wave scholars to identify every homage in this film. Surely some little scene includes a tribute to Hitchcock, another to Rossellini, another to Bergman ... of course the grandest is to “Citizen Kane,” as Ferrand dreams of swiping publicity photos of the film as Truffaut surely did as a boy (and realizing “Meet Pamela” isn’t in the same league).

“Day for Night” won the Oscar for best foreign-language film of 1973, a significant achievement. Equally impressive is that a year later (because of the Academy’s timing rules, which were different then for foreign-language film and individual categories), in a landmark year for American cinema, it produced Oscar nominations not only for Cortese but Truffaut as best director (he lost to Francis Ford Coppola, “The Godfather, Part II”) and Truffaut, Jean-Louis Richard and Suzanne Schiffman for best original screenplay (they lost to Robert Towne, “Chinatown”). It missed a best picture nomination, something achieved in the years before by Sweden entries “Cries and Whispers” and “The Emigrants,” but neither of those exceptional works received the foreign-language Oscar.

Truffaut was a revolutionary. He rose to prominence critiquing establishment cinema, then ushered in the style of filmmaking in the late 1950s known as French New Wave (the term first appears in the New York Times on Jan. 20, 1960, according to an online search) with frenemy Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol and others. “Day for Night,” a decade and a half later, is a nod to the timeless art of filmmaking, dedicated to Dorothy and Lillian Gish. It evidently did not register with fellow upstart Godard. In the 2009 French documentary “Two in the Wave,” Godard is said to have walked out of “Day for Night” and written Truffaut a scathing letter calling him a “liar” and mocking the reference to movies being “like trains in the night.” Truffaut’s 20-page response permanently ended their collegiality.

Truffaut passed away in 1984 at age 52. “The 400 Blows” is his acknowledged masterpiece, the only one of his films in the top 50 on the last installment of the prestigious Sight & Sound once-a-decade, greatest films list. But in Truffaut’s New York Times obituary, “Day for Night,” in the fourth paragraph, is the first film mentioned — one that can stand for as long as they’re making movies.

4 stars

(September 2017)

“Day for Night” (1973)

Starring Jacqueline Bisset as Julie Baker ♦

Valentina Cortese as Séverine ♦

Dani as Liliane, la stagiaire scripte ♦

Alexandra Stewart as Stacey ♦

Jean-Pierre Aumont as Alexandre ♦

Jean Champion as Bertrand, le producteur ♦

Jean-Pierre Leaud as Alphonse ♦

François Truffaut as Ferrand, le réalisateur ♦

Nike Arrighi as Odile, la maquilleuse ♦

Nathalie Baye as Joëlle, la scripte ♦

Maurice Seveno as Le reporter TV ♦

David Markham as Dr. Michael Nelson ♦

Bernard Menez as Bernard, l’accessoiriste ♦

Gaston Joly as Lajoie, le régisseur ♦

Zénaïde Rossi as Madame Lajoie ♦

Xavier Macary as Christian ♦

Marc Boyle as Le cascadeur anglais ♦

Walter Bal as Walter, le chef opérateur ♦

J.F. Stevenin as Jean-François, l’assistant réalisateur ♦

Pierre Zucca as Pierrot, le photographe de plateau

Directed by: François Truffaut

Written by: François Truffaut

Written by: Jean-Louis Richard

Written by: Suzanne Schiffman

Producer: Marcel Berbert

Music: Georges Delerue

Cinematography: Pierre-William Glenn

Production Design: Damien Lanfranchi

Film Editing: Yann Dedt, Martine Barraque

Art Direction: Damien Lanfranchi

Costumes: Monique Dury

Makeup and hair: Malou Rossignol, Fernande Hugi, Thi-Loan Nguyen

Production manager: Claude Miller

Assistant director: Suzanne Schiffman

Assistant assistant director: Jean-François Stévenin

Sound mixer: Antoine Bonfanti

Sound: Rene Levert, Harrik Maury

Stunts: Marc Boyle (uncredited per IMDB)

Dedicated to: Dorothy Gish

Dedicated to: Lillian Gish