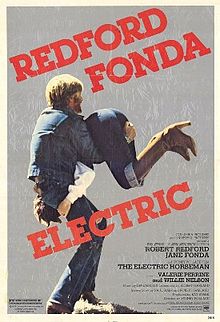

‘Electric Horseman’: The dawn

of a decade, Sonny side up

Sonny Steele is probably leading a beautiful horse to ruin.

That is not the ending we get in “The Electric Horseman,” a film unfazed by long-term outcomes. Clumsily made, by the exceptional director Sydney Pollack, it ultimately resonates with a beautiful poignancy, ranking high among the most pleasant tragedies.

It is halfway through the film when Sonny reveals his end game: He is going to set prized thoroughbred Rising Star loose into a pack of wild horses. In confiding this information, Sonny admits it might not work, that Rising Star might not make it. The reaction from Sonny’s one-person audience to this disclosure is not concern for the animal’s welfare, but excitement: We’ve got a story here!

Surely if Sonny were sober when he began this journey, it would’ve occurred to him that the Utah mountains — and perhaps the journey to get there — might not be survivable for a premier racehorse. But we have been conditioned from early scenes that corporate ownership is destroying Rising Star, that survivability (not to mention virility) depends on a clean break, and so there is no safer place on earth for Rising Star than Silver Reef.

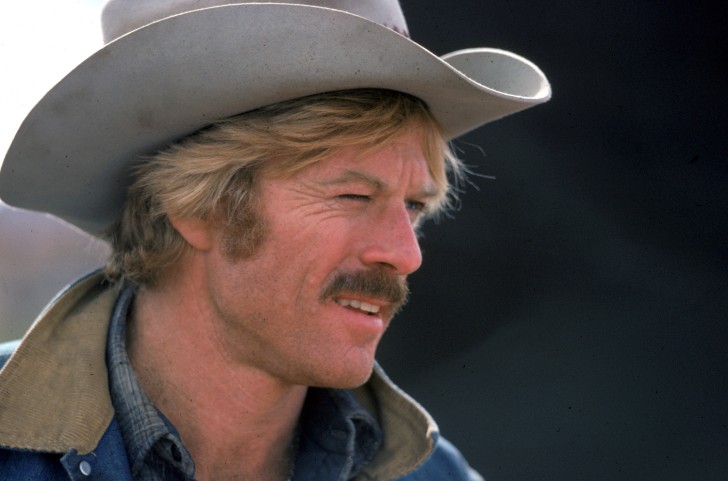

“The Electric Horseman,” starring Hollywood immortals Robert Redford and Jane Fonda, was released in late 1979. Jimmy Carter was president, Americans were held hostage in Iran, inflation was out of control. Yet somehow, there is a beautiful sense in this film of “Morning in America,” a slogan attributed to Carter’s successor several years later. This is absolutely an ’80s picture, not a ’70s one. “Horseman” oozes revival. It’s a rugged cowboy, beaten down in the ’70s, taking life by the horns again as a fresh decade looms. Sonny is probably a bit too old (Redford was 43 upon the film’s release) to have been a former candidate for Vietnam, but nevertheless there are no such scars suggested here. No Watergate, no energy crisis, no California radicals, no New York City crime waves. Disco is being lampooned. It’s a new world, wide open and boundless, waiting for us to put our best foot forward.

Pollack, helming a story credited to Shelly Burton (story), Robert Garland (screenplay) and Paul Gaer, appears to draw some inspiration from Paddy Chayefsky’s “Network.” A colorful employee has gone rogue. This is a disturbing development for the corporate bureaucrats, until they realize they are benefitting from it. But the endings must diverge. A human being, including an older one in need of psychiatric care, can be exploited in the movies. A horse cannot. Who’s ever on the side of Rising Star will prevail.

“Horseman” is built upon a delicious, morally ambiguous concept. This is a spectacular, creative conflict that does not involve a gun. A drunkard has stolen a prized animal. In general, this should be a crime, but in this case, not necessarily, and the rapidly fluctuating opinions of Sonny’s act prompt thoughtful media battles in which strategies must change on the fly.

In “Horseman,” the outdoors are a pleasant oasis to life. No one is going to die here; nobody’s life is in danger. If anything, the journey is almost ridiculously sanguine. The production apparently faced far more difficult elements than the characters do in the film. Sonny and Hallie encounter no storms, no bears, no rattlesnakes, not even a cricket late at night. Sunshine is rampant. Their only enemy is detection, which seemingly could be accomplished by a state police helicopter, but no matter.

One can set aside everything that “Horseman” is not. Roger Ebert, in a three-star review, mistakenly called it an “oddball love story” with a “happy ending.” Vincent Canby wrongly describes it as a “romantic comedy.” Gene Siskel missed the boat in dubbing the film a “romantic, light comedy.” It is not a romance. It is not an animal-rights film. It is not an opus on the environment or media concentration, nor is it a takedown of capitalism.

Rather, it’s a story of moments. Fleeting ones. Two characters criss-crossing in time, bringing out the best in each other — but only for a moment that will soon pass.

It is remarkable that the term “western” does not appear at all in Ebert’s review, and only once, as part of the conglomerate name Gulf & Western, in Canby’s. “Horseman” is assuredly a western, one refreshingly devoid of guns and intensity but very much a battle of terrain. Heightened by Pollack’s typically stunning vistas (the cinematographer is Owen Roizman) that are as peaceful for viewers as they are for the horse, it’s a unique battle about who can best navigate that terrain as well as the distant news media, in a small amount of time.

Throughout the journey, Pollack and his stars paint a beautiful contrast. Sonny Steele is the male, the rugged outdoorsman. Yet Hallie Martin, after an uncertain start, proves the more vigorous on this journey. She is not as tired, not as “bent” in the morning. She is paying more attention to the details than he is. Gradually, a solemn truth emerges that will culminate in a bus ride — she is an elite, at the prime of her career. He is a former elite, winding things down. They are meant for this trek. Not for each other.

The first 30 minutes of “Horseman” are largely unnecessary, a pedestrian, uninspired, scattershot production. Yet the film overcomes its awkward beginnings with its simple, surprisingly powerful conclusion. After all of this, they are down to a doughnut and candle. And memories. Sonny Steele takes the goodbye in stride. Fonda’s face in this diner betrays the realization of a tiny tragedy, reminiscent of “The Bridges of Madison County” — that people are indeed meant for each other, sometimes for a lifetime, sometimes for just a moment, and no matter how glorious, there is a kind of permanent heartbreak associated with the latter.

Robert Redford has the top billing. He makes the parting powerful with his remarkable aloofness as Sonny. He never flinches in character. He’s the type of soulmate women think they might have found but can never be 100% certain of. He might call when she most needs a pick-me-up, or never answer her e-mail.

Sonny never yields to the temptation of emotion. Early on, he coldly, but convincingly, defends his Ampco work to his associates, who indicate they liked working with him a lot more when he was riding bulls. Ampco may have given him a ridiculous job, but the pay’s good and his body can no longer handle being stomped on by animals. A home in Malibu isn’t Sonny’s style, it is agreed (in dialogue, unfortunately, and not shown in any way), but it beats the “bacon and beans circuit.” He has lingering pride in his fast-fading rodeo accomplishments but no interest in celebrity. He doesn’t pursue women, but takes whatever he gets. He doesn’t see his release of Rising Star as a game-changer for himself, but an obligation. He sleeps with Hallie, eventually ... but does he actually need her? By the end, he doesn’t know.

And then there is his complicated connection to the other co-star. What is Sonny’s motivation for taking the horse? Like many films involving horses, the human hero’s greatest attribute is his ability to calm and control the animal, something Redford also did two decades later in “The Horse Whisperer.” There is a powerful metaphor here in Sonny’s clothing, that Ampco has festooned him with just as much silliness as it has the horse; it’s unhealthy and both need an escape. But there may be less outrage here than the sense that Sonny is just tired of being a has-been. Is he doing this, as we want to believe, for Rising Star’s well-being, or to give himself a project? It’s something of both. His nonchalant exit from Caesars tilts toward the latter.

In many films, such as “Rocky” or “Norma Rae,” an underdog everyman will win people over on sheer determination. Sonny Steele is oblivious to such sentiments. He has long since grown immune to people cheering him. He has merely identified a wrong and is fixing it. Only when the Ampco P.R. department maligns his character is he prompted to say — unintentionally, it should be noted — why he has taken Rising Star.

Pollack’s awkward beginning depicts a generic stallion (lacking Rising Star’s identifiable white streak) galloping down a splendid, boundary-less hill. This curious motif, apparently a celebration of wild horses, is quickly given a too-abrupt transition to a rodeo cowboy who does not resemble Redford (who sports a mustache in this picture, a rarity for him) but may or may not be Sonny Steele, and from there, the backstory is all Sonny’s. This rough opening mars a beautiful parallel between the lyrics of Willie Nelson’s version of “My Heroes Have Always Been Cowboys” (the credited writer is Sharon Vaughn) and Steele’s career; first optimism and reverence for his profession and then, largely shown through posters and marquee signs, Steele’s apparent decline into a third-rate corporate attraction.

There is a curious choice of names here. The most famous Sonny is quite likely Sonny Bono. There are Sonny Liston and Sonny Jurgensen. Cinematically, there is Sonny Corleone, a character who is tough but reckless and immature. It’s a nickname, Liston aside, that suggests a colorful, carefree, happy-go-lucky person. Its homonym is associated with happiness. But there’s another side to this Sonny, a steel-tempered resolve to do what’s right.

Things have nearly hit rock bottom when Sonny arrives for a typical stadium appearance, apparently tardy, only to see an impostor billed as Sonny Steele riding a horse around a field. “That’s not me,” Redford observes to the promoter, a comment of impressive subtext with significant longer-term ramifications.

Countless films introduce us to a character with a hangover. This is disappointing on the part of the writers, to not weigh down Steele with a more original problem. But “Horseman” is significant in that what turns Sonny around is not a woman, but a thoroughbred, a reverential nod to the pull that wildlife has on humans. We find Sonny on the ropes in a casino, yet just hours later he is galvanized. Steele was OK with being a cartoonish pitchman, but not OK with being party to abuse of a horse. In one of the film’s most powerful lines, Sonny tells Ampco’s CEO, with a certain assertiveness for a change, “It just don’t feel right,” and we are no longer listening to a drunkard, but a caretaker of his craft.

Depicting the swing in public sentiment was, for some reason, not easy for Pollack. He shows no pro-Sonny rallies; a bureaucrat reveals in a hotel suite a T-shirt that kids are selling on the street. Sonny by necessity must avoid the general public, which is a problem. Pollack resorts to an unexpected encounter with Wilford Brimley’s rancher, who seems gruff enough to turn Sonny in before surprisingly offering him safe passage. A police officer then admits he doesn’t want to catch Steele either, “except for that reward,” another testament that Sonny is doing the right thing while the conglomerate is doing the profitable thing.

The notion that Steele could ride Rising Star out of Caesars Palace and down a quiet Vegas street without detection or pursuit defies belief ... but not completely. Pollack somewhat makes it plausible with his carnival-like casino atmosphere; if you think a guy riding a horse off Las Vegas Boulevard is strange, you haven’t been there very often.

The Vegas Strip, like Steele’s alcoholism, seems too easy and obvious of a foil here for Rising Star’s fish-out-of-water plight. But in fact Vegas is the essential base for this film because it puts Steele close enough to that Utah vista that Pollack covets. Were this Ampco convention in Madison Square Garden, there’d be nowhere to run.

Mostly, though, what happens in Vegas should’ve stayed on the cutting-room floor. Pollack swamps Sonny with needless hangers-on that distract the viewer. Somewhere in the orbit are cheerful Ampco distributors, an ex-wife, and old Gus, who supplies the camper Sonny needs to make an exit. Their purpose is twofold, to show the types Sonny is known to deal with, and (much more importantly) to give Hallie some sources. “Horseman” is notably the first credited film appearance, according to the Internet Movie Database, for Willie Nelson. However, Nelson’s role as Wendell, one of Steele’s two handlers from the old days, is superfluous and feels like a favor from Pollack in exchange for supplying much of the soundtrack. (Nevertheless, this relationship paid off handsomely the following year when Pollack executive-produced Nelson’s spectacular “Honeysuckle Rose.”)

Apparently, this is the corporate story: Steele is employed by Ampco, a conglomerate, which also owns Rising Star, presumably for promotional reasons and other synergies. Steele’s assignment is to sit on Rising Star in a Vegas casino and shout “Ranch Breakfast!” during an Ampco products convention. This would figure to be a tiresome corporate event for wholesalers and dealers of the company’s diverse products. But this year, the stakes are unusually high. “They’re trying to buy this big bank,” Wendell informs an intoxicated Steele, which perhaps explains how this event could possibly draw to Nevada a New York television reporter who’s not even sure what person she should interview.

Sure enough, a questioner (we learn later he’s from the Washington bureau of the New York Times) at the press conference wonders if Ampco expects “opposition” (unclear if from shareholders or regulators) to its “takeover” of OmniBank. The corporate response is that this is a “merger,” and the company is “confident” that its “generous” offer will be accepted.

This is years before RJR Nabisco, perhaps the most famous leveraged buyout, chronicled in the “Barbarians at the Gate” film and book. Pollack (and perhaps his stars, who advocate many causes) are suggesting that when corporations get too big, they get too good at making money while losing their focus and heart and ultimately emasculate their resources. Goodness knows why viewers are forced to contemplate how a bank tender offer fits into Sonny’s awakening. We get it — Ampco’s a conglomerate, and it’s trying to be even more of a conglomerate.

John Saxon, as Ampco CEO Hunt Sears, is a face you’ve seen before (“Enter the Dragon” among scores of credits) but a name you can never recall. Pollack gives him a chance here, and he resonates as a capable and cordial, if coldly amusing, leader swallowed by the corporate rat race. He is alarmed to learn how Rising Star is being treated. But this is business, not humanitarianism, and there’s no point in trying to make sense of the advertising tactics of his own company. He is not so much a villain here as a casualty. It’s the corporation and what it demands, not the people running it, that is at fault.

Fonda, as New York TV reporter Hallie Martin, is introduced in an elevator. A hat partly covers her face and she has the appearance of a detective. She is savvy enough to realize from an innocuous conversation why an apparent non-attraction such as Steele might be worth covering in Vegas. She has no idea what’s about to happen, but her sixth sense tells her something might. And so there is a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy as her questions to a drunken Steele about his self worth perhaps help Sonny make up his own mind.

Coincidentally, Fonda also plays a TV reporter in “The China Syndrome,” released months earlier. Like many movie stars, she excels in a typical television news set. In “Syndrome,” her character is actually underrated, providing her the opportunity to soar in a crisis. Unfortunately, “Horseman” installs her already at the top of her game and only rarely depicts her in front of the camera.

Fonda, on the short list of contenders for greatest film actress, was 42 when “Horseman” was released. In this picture she is in fantastic shape, something which would become her hallmark within a few years. Her famous beauty is intact but often not allowed to flourish under a decided middle-age, 1980-esque hairstyle which perhaps was cutting edge at the time but unfortunately seems like a dig at ’70s TV news fashion.

Hallie’s heroic contribution is reporting Steele’s unknowingly candid remarks about the horse. She astutely realizes that Sonny’s unscripted comments during their planned taping are far more powerful than the ridiculous posed statement he is about to say. Her release of these remarks clears Sonny of legal jeopardy and generates support they will need later. However, neither Pollack nor Fonda is very imaginative in how Hallie procures this particular statement from Sonny. In fact it’s a trick borrowed from “The China Syndrome,” in which a character is somehow so clueless as to not recognize a camera is on.

Fascination with Fonda stems as much from her prodigious talent and beauty as her polarizing politics. Probably no actor since the blacklist era, perhaps even earlier, has been condemned or challenged as vehemently. She toured North Vietnam in 1972 and sat on an anti-aircraft gun and permanently struck an American nerve that in some quarters still reverberates. To this day, boycotts are organized against her films. In 2011, cable shopping channel QVC was compelled to cancel a Fonda appearance after protests. There is a determination to that opposition as well as an added mystique to Fonda because of it. Her films and products — even when it becomes her descendants attending tributes on her behalf — will forever be proxy battles in America’s Vietnam experience. “The Electric Horseman” occurred after Fonda’s career revival in the late ’70s, when opponents had other samples of her work to target, and feels far removed from lightning-rod politics.

In this subdued role, she only shines with an excitable persistence that is very believable of an elite news reporter. “Let’s go into town and have a cup of coffee and talk about it. My treat,” she says during a remarkably stressful moment, one of those bizarre quips we’ve all heard from time to time that lighten a crisis. “I think I’ve broken my leg,” she tells Steele in another scene and, perfectly capturing the rapport they’ve built thus far, adds, “What are you gonna do, shoot me?”

After their first night of romance, Hallie anxiously says in the morning, “I’m still here” — an incredibly simple observation that seems irrelevant until one considers how quickly this window will close.

Why is Hallie not married? It could be inferred that she is too wedded to her work. Or too relentless. Sonny offers an opinion of sorts, that she is too “clever.” “Horseman” doesn’t consider her backstory relevant. But there are hints, as Fonda masters the voice of honesty. When Hallie is finally calm, at the end of the day, her tone and diction change to complete sincerity. The truths she tells are not particularly significant, but this is finally a refreshing no-b.s. zone, the way real people talk to each other. If he had actually wanted to add an edge, Pollack has the opportunity here for a serious twist, using Hallie in these situations to actually mislead Sonny. Pollack, apparently like Sonny, doesn’t want her to be that clever.

Even so, most of the best lines are delivered by Redford. “There's coffee from last night. It’s, uh, probably cold,” Hallie says anxiously, but Steele gets to reply, “Probably is if it hasn’t been heated.” In the same conversation Hallie urges Steele to eat; “They say breakfast is the most important meal of the day.” “I- I know,” Steele says with disbelief that makes his response perhaps the film’s funniest line. “I’m the one that said it.”

“You know what you need,” Sonny tells Hallie, pausing with a sleeping bag tease that is perhaps the best curveball, “a pair of proper shoes.”

Pollack and Redford put much at risk with a crucial scene, around the 40-minute mark, when Hallie has reached Steele’s campsite at night. In his only aggressive behavior of the film, Steele first unnecessarily tackles Hallie, then slaps her. “How did you find me?!?!” he demands. Is Sonny unhinged? No. This confrontation works, because of Fonda. She deals with people under pressure and this is how people under pressure act. She’s tough, accustomed to this kind of encounter. That she accepts it means the audience can too. She has elicited determination from Sonny for the first time. We need to know, is he serious? From there, we begin our glorious trek to freedom.

“Horseman” takes a detour when Hallie, having tracked Sonny down, is compelled to return to Vegas. This is frustrating to the viewer, who has already seen enough slot machines. But Hallie needs a metropolis to air her report of finding Steele and Rising Star. Nowadays she would Skype it on location and refuse to leave Steele’s side. But this is 1979, when our media was — wonderfully in so many ways — highly formal, and limited.

Assisting Sonny in his escape could be chalked up as necessitated by good reporting. Sleeping with her subject, however, is an unmistakable ethical breach by Hallie. Should it offend hardened media critics? Surely when this adventure is over, there will be whispers. “She spent several days with this guy in the mountains ... what do YOU think happened,” they’d say.

This would be a fair criticism, given that Pollack’s references to the media are unusually savvy. Characters indicate that contacting the advertising department, not the editorial department, is the way to co-opt a story. There is fair debate as to whether Hallie is actually aiding a felon. Instead of a ridiculously overzealous press conference (think “Rocky II,” III and IV) in which questioners sound as if they’ve got the next Watergate, Hallie is depicted rightly wondering if the press events on her schedule are even worth covering.

Rising Star cooperates splendidly through the entire film, too well actually, handling the atrocious Vegas surroundings like a pro and quietly lurking in the background of Redford and Fonda’s scenes. He may be a champion thoroughbred, but in this film he is a docile pony. Never once does he bristle, either in a crowded camper, a semi truck, or a long hike up a Utah mountain. Somehow, this champion racehorse has the endurance to outrun police cars at the end of a miles-long dash through uneven turf. (In one of those things that can’t possibly be rehearsed but seems appropriate for the film’s tone, Rising Star noticeably relieves himself after the escape, his handlers oblivious.) This cannot be the life he is accustomed to. The implication is that he is responding to Redford, not the drugs, and is healthier for it. Pollack errs in not depicting Rising Star as agitated by Vegas. Other than sniffing eucalyptus, it is unclear exactly what treatment Rising Star is receiving from Sonny. The horse is initially “stoned,” we are told, and Sonny is capable of making him act equally professional without the drugs.

What constitutes an inhumane environment for an animal? One hopes that society somehow would prevent a racehorse from being paraded through a casino. But we know that one of the most popular Vegas acts for years involved rare white tigers, one of whom critically injured celebrated entertainer Roy Horn. We’ve seen Clydesdales hauling Budweiser wagons, and we’ve seen horse-drawn carriages in other movies offering romantic rides on big-city streets. Organizations such as the Humane Society, Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and PETA have to pick their battles.

Whether Rising Star, unshooed and not knowing where his next meal would be coming from, could thrive or even survive in the wild is apparently uncertain enough for Pollack to go full bore on this concept. To consider an extremely highly trained, medicated and pampered creature such as Rising Star as handling a trek with Steele, let alone fending for itself in unknown territory without injury or agitation, defies common sense. But is it possible? If so, it’s evidently not recommended. The Humane Society of the United States lists 6 approved methods for “relinquishing” a horse, none of which involves turning it loose in a pack of wild horses ... probably because there are too many of them for the government to handle, threatening not only the available limited resources but creating opportunities for poachers looking to cash in on overseas horse-meat demand.

“I’m gonna get him back to where he was, what he was,” Sonny declares to Hallie in perhaps the film’s most unconvincing line. “It’s in his blood. He knows what to do, he’s just half-forgotten.”

What Pollack adds in lightness, he sacrifices in drama. Characters regularly tell silly fibs or seek to poorly disguise themselves but generally get away with it. Sonny twice is compelled to pretend that he is disturbed at hearing Hallie predict he is going to Rimrock Canyon. This produces a rare mistake from Hallie that seems beneath her. “I am in as much trouble as you are. If I go back there I’m gonna have to tell them everything I know. ... It’s called misprision (sic), a felony,” she says.

“Horseman” is not a film of diversity. Virtually every character who speaks is over 40. Only a handful of non-white faces are seen in the entire movie, in the background at a mall and grocery store. Even the people in Vegas are roughly 99% white. Some films would introduce an ethnic character to help the heroes’ enlightenment along their journey. Pollack chooses Wilford Brimley, who looks older than he really is, to provide the key assist, and otherwise, probably wisely, wants his 2 stars to make it on their own.

There are hints of serious product placement, and not just the fountains of Caesars Palace. Michelob bottles are seen early. Hallie uses a Sony camera. She is said by Sonny to be a shopper of “Bloomington’s or Bloomingburg’s or wherever the hell it is,” then Hallie opts to state the correct name for the record. Redford notably wears Levi’s. Wilford Brimley appears to be wearing Wrangler jeans.

Nearly 100% — or close to that number — of films of the 1970s had to feature a car chase of some kind, and “Horseman” is unfortunately no exception. As another actor who does not adequately resemble Redford guides Rising Star through a rural Nevada neighborhood, first it’s the Keystone Kops on motorcycle giving chase, then the squad cars. One has to wonder what the police game plan was for stopping the horse. Ride a motorcycle alongside it until you can leap into the saddle with Steele? The music of this sequence (Dave Grusin is credited for original music) matches the slapstick material with echoes of late ’70s/early ’80s TV fare and is at odds with Nelson’s bookending graceful melodies.

In an embarrassing glitch that will only be noticed by those paying close attention, Pollack has obviously flipped his final images of Rising Star running free in Silver Reef, to show the horse running both left to right and then right to left. The strides from the 2nd angle seem too symmetrical, and one realizes the white streak on Rising Star's head is pointing the wrong direction from the latter view.

The film received one Oscar nomination, for sound, for Arthur Piantadosi, Les Fresholtz, Michael Minkler and Al Overton Jr. The winner was the crew of “Apocalypse Now.”

In the richly satisfying ending, Steele and Martin accept the end of their journey. “I keep wantin’ to thank you ... but then I keep wondering, what for?” Sonny observes. “Maybe it’s for how I’m gonna feel whenever I see you on ... television.”

In “Continental Divide,” a legitimate romantic comedy, a couple entrenched in extremely unyielding environments somehow makes things right with a marriage certificate. In “Horseman” there is undeniable lament from Hallie that, ultimately, this was an assignment; you can’t marry your job. Sonny has gained a mild respect for the news media and a greater appreciation for letting one’s guard down — a bit.

Is Sonny headed back to the bottle? Unfortunately, the answer seems quite possibly yes. He is out of a job, and out of a horse. He tells Hallie he will find something “simple ... hard ... plain ... quiet.” Sonny does not seem interested in a speaking tour nor any more endorsements. But there are no more compromises either. His darkest days are behind him.

3.5 stars

(April 2013)

“The Electric Horseman” (1979)

Starring Robert Redford as Sonny ♦ Jane Fonda as Alice “Hallie” Martin ♦ Valerie Perrine as Charlotta ♦ Willie Nelson as Wendell ♦ John Saxon as Hunt Sears ♦ Nicolas Coster as Fitzgerald ♦ Allan Arbus as Danny ♦ Wilford Brimley as Farmer ♦ Will Hare as Gus ♦ Basil Hoffman as Toland ♦ Timothy Scott as Leroy ♦ James B. Sikking as Dietrich ♦ James Kline as Tommy ♦ Frank Speiser as Bernie ♦ Quinn Redeker as Bud Broderick ♦ Lois Areno as Joanna Camden ♦ Sarah Harris as Lucinda ♦ Tasha Zemrus as Louise ♦ James Novak as Dennis ♦ Debra L. Maxwell as Convention Hostess ♦ Michele Heyden as Sunny Angel ♦ Robin Timm as Model Narrator ♦ Patricia Blair as Fashion Narrator ♦ Gary M. Fox as Bellman ♦ Richard Perlmutter as Desk Clerk ♦ Carol Eileen Montgomery as Carol ♦ Theresa Ann Dent as Ranch Breakfast Model ♦ Perry Sheehan Adair as Mrs. George Phillips ♦ Sarge Allen as Mr. Phillips ♦ Sylvie Strauss as Matron ♦ Richard Knoll as Dealer ♦ Angelo Giouzelis as Maitre D’ ♦ Mark Jamison as Major Domo ♦ Brendan Kelly as Grocer ♦ Sheila B. Wakely as Store Clerk ♦ X. V. Kelly as Sheriff ♦ Gary Shermaine as Trucker ♦ Gary Liddiard as Townsman ♦ Jerry Kurland as Ampco Personnel ♦ J. Carlton Adair as Ampco Personnel ♦ Charles J. Monahan as Ampco Personnel ♦ George W. Etter as Ampco Personnel ♦ Raymond G. Maupin as Ampco Personnel ♦ Bob C. Barrett as Ampco Personnel ♦ Red McIlvaine as Reporter ♦ Frank Nicholas as Reporter ♦ Johnny Magnus as Reporter ♦ Vic Vallaro as Reporter ♦ Bob Bailey as Reporter ♦ Roger Lowe as Reporter ♦ Rita Picking (uncredited per IMDB) as Woman blowing kiss to Sonny at Caesar’s Palace ♦ Sydney Pollack (uncredited per IMDB) as Man who makes pass at Alice

Directed by: Sydney Pollack

Written by: Robert Garland (screenplay and screen story)

Written by: Paul Gaer (screen story)

Written by: Shelly Burton (story)

Producer: Ray Stark

Associate producer: Ronald L. Schwary

Original music: Dave Grusin

Cinematography: Owen Roizman

Editing: Sheldon Kahn

Casting: Jennifer Shull

Production design: Stephen Grimes

Art direction: J. Dennis Washington

Set decoration: Mary Swanson

Costume design: Bernie Pollack

Makeup and hair: Marine Pedraza, Bernadine M. Anderson, Gary Liddiard

Production manager: Ronald L. Schwary

Stunts: Roger Creed (uncredited, per IMDB), Bruce Paul Barboar, Corky Behrle, Ken Endoso, Ralph Garrett, Mickey Gilbert, Mollie McCall, Conrad Palmisano, Mary K. Peters, Rick Seaman, Sonny Shields, Rock Walker