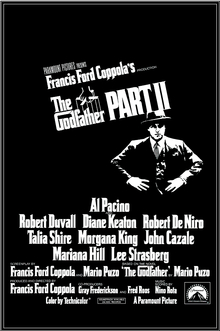

Even better than the first:

‘The Godfather: Part II’ is

the greatest film ever made

“The Godfather: Part II” is the fulfillment of the tragedy, which is why it is superior to the first film and rightly regarded as the greatest motion picture ever made.

Most don’t see it that way. The latest Sight & Sound poll puts “The Godfather” at No. 12 and “The Godfather: Part II” at, somehow, 105. The American Film Institute currently puts the first film at No. 2 and the sequel at 32. Roger Ebert went from 4 stars (1972) to 3 stars (1974) and, after installing the original as one of his earliest Great Movies, waited another 11 years to accord similar recognition to the sequel.

“Part II” upends the notion of neat, singular movie criticism, among the reasons it is a landmark production. A lot of critics prefer to consider the two films as one movie. In a way, they are. The material in “The Godfather” is sandwiched by the parallel stories in “Part II,” a concept that likely has never been attempted since. Some say “Part II” begins during the first film, when Michael confronts Moe Greene in Las Vegas. Some have observed that the second film makes no sense for anyone who hasn’t seen the first — quite possibly a valid hypothesis, if there were actually anyone eligible to test it. In September 2024, Manohla Dargis of The New York Times writes that “Part II” was “once thought difficult by many.”

Pauline Kael, reviewing “Part II,” writes, “The second film shows the consequences of the actions in the first; it’s all one movie, in two great big pieces, and it comes together in your head while you watch.” Kael adds that “You’d have to have an insensitivity bordering on moral idiocy to think that the Corleones live a wonderful life, which you’d like to be part of.”

It is said that the second film is about greed, that a talented man lost his soul and any connection to decency because of his remarkable success as a gangster. While Vito stood up to thugs, freed his neighborhood and reaped rewards as a result, Michael did things in reverse, measuring every relationship as a zero-sum game.

But the second film is better explained by the truth that charismatic leaders are virtually irreplaceable. Yes, supposedly de Gaulle and several others claimed the opposite. But when an organization succeeds disproportionately under one person, history shows it’s never the same afterwards. Splendid examples include megachurches and college sports teams and political parties. UCLA will never hire another Wooden; Duke will never get another Krzyzewski. George H.W. Bush and Al Gore would say and do the same things as their presidential bosses but wouldn’t elicit the same reactions as contenders for the same job. “The Godfather: Part II” is a blunt demonstration that the Golden Age of the Corleones is over, no matter who follows Vito.

But what a way to go out. The final 40 minutes of “Part II” are the greatest filmmaking ever accomplished. Brothers are briefly reunited with the tiniest hint that the warmth of the first film still could be recaptured before this is all over. Immediately, that whim is put to rest by a relentless revenge campaign far more disturbing than the ending of the first film. Hatred swells for Michael until Francis Coppola concludes with a look back at Michael’s decision to join the Marines, and finally, the most powerful film ending, the contemplation on the face of Michael Corleone of roughly 380 minutes of drama.

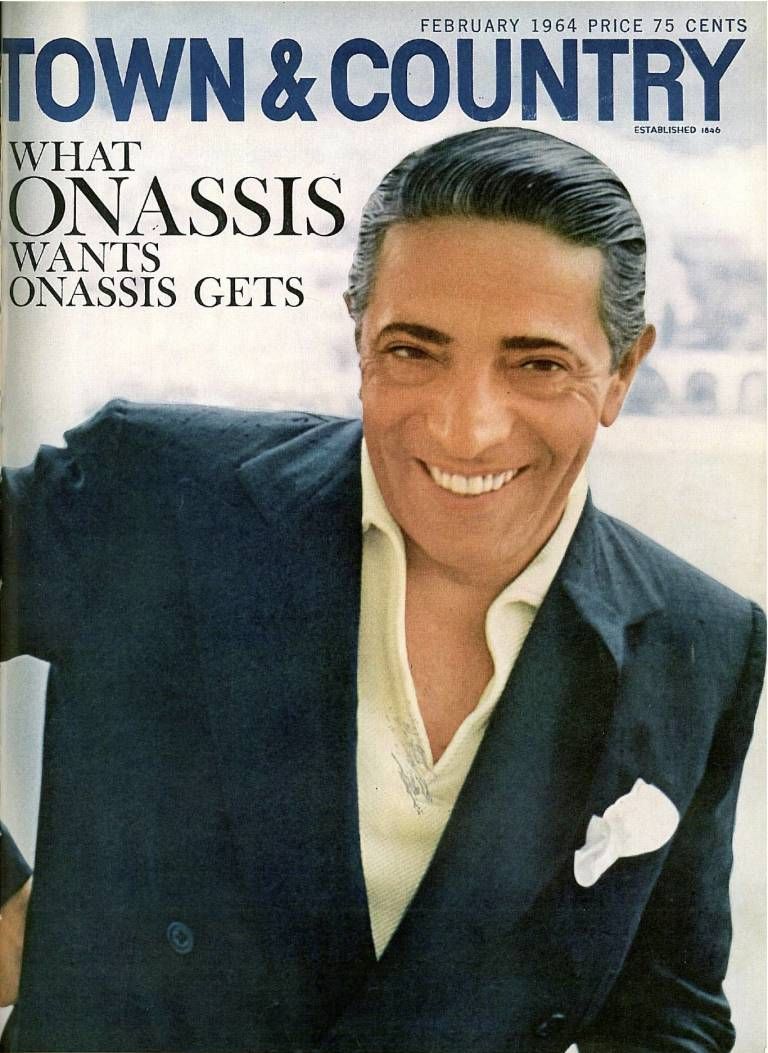

The filmmakers behind “The Godfather” insisted the work was based on research by Mario Puzo and was not reflective of Italian Americans. Who was the model for Michael Corleone? Michael must have been at least partly inspired by Aristotle Onassis, the Greek shipping magnate and world’s richest man. Onassis was not a gangster nor a killer. He was a dubious businessman of enormous wealth who attempted to buy legitimacy, which for Onassis could be measured by the caliber of celebrities who would sail on the Christina O yacht. Onassis may have gone unnoticed by Americans and Hollywood producers except that, just as “The Godfather” (the novel) was coming to fruition, he persuaded the world’s most eligible prize, Jacqueline Kennedy, to marry him, superseding the previous top rung on his ladder, Maria Callas.

Onassis falls somewhere between the birth dates of Vito and Michael Corleone; his life parallels both. Born in 1906, he grew up in the Aegean city of Smyrna, his father prosperous. When Turkey claimed Smyrna in 1922, the young Onassis fled to Argentina. He created an import-export business and supposedly made a fortune in tobacco, then built a shipping line and moved to New York, then entered the hotel business in Monaco where, unlike the Corleones in “The Godfather,” he was pushed out of town by Rainier.

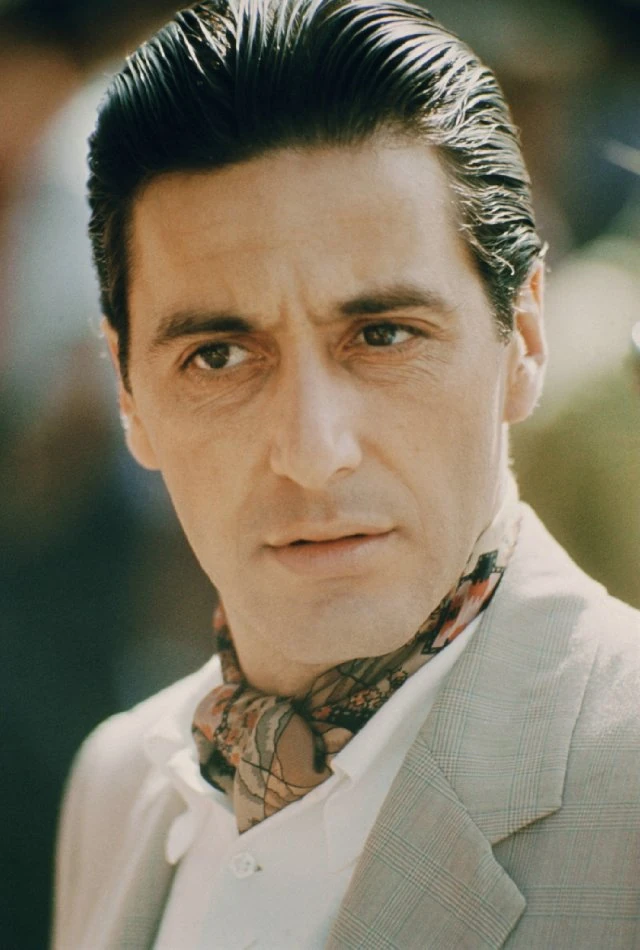

While Al Pacino is far more handsome than Onassis, notice the similarities. Not in the first film, but the second. It is the eyes, not so much the nose or mouth. In some photos, Onassis has a side part; in others, his hair is slicked back, much like the differences in the look of Michael Corleone at his Tahoe ranch and then during his trip to Cuba.

Obviously, there’s some kind of resemblance: In 2013, Pacino was announced as portraying Onassis in Fernando Meirelles’ “Nemesis.” There are several articles about the casting within the last 10 years; evidently the project has been shelved.

Legitimacy is a very difficult concept to illustrate. Yet it is explained prominently by Michael’s wife, Kay, in the early scenes of “Part II.” Even the greatest cinematographers cannot easily show famous people unwilling to be in the presence of Michael Corleone. Does Michael even care? Admiration and even respect from others seem irrelevant to him. His motivation is to outduel his opponents — either for financial prizes or utter survival. Kay on the other hand seems to think that with a little effort, the Corleones could be invited to the White House or the Academy Awards. That’s not a notion taken seriously by Michael, or anyone making or watching the film.

Notice that in both movies, it’s not the Corleones who shoot first. In each, they are portrayed as possessing some kind of leverage, and it’s the rivals who launch the mayhem to disrupt the Corleones’ calm, cool order. This type of higher moral ground is equivalent to the best house in a bad neighborhood. Without it, we might not be able to accept the Corleones, at least not all of the hugs and loyalties of the first film.

In the first film, the Corleones are the moral compass. They are moguls of the softer vices, gambling and prostitution, activities that parts of the country and rest of the world had moderately legalized. As a bonus, they are enforcers who right the wrongs of the corrupt legal system, serving society by meeting the considerable demand for underworld services with a sense of standards and integrity. They will do more for the common people they encounter than the common people merit. This brings the family protection from more dubious elements of the police department and resistance from other families who believe the Corleones’ stubbornness is allowing other organized-crime outfits to put some of the families out of business.

Vito may have felt beloved, and he was — notice Tessio doesn’t betray Vito but Michael — but Michael believes the family’s employees are only loyal to the dollar, not the don. He says as much to Tom Hagen in “Part II”: “See, all our people are businessmen. Their loyalty is based on that.” Is this a shortcoming on the part of Michael? The first film from the opening scene weighs revenge vs. business and constantly suggests the former is counterproductive to the other. To succeed at both, Michael finds a way to marry the two, apparently with Vito’s blessing.

The first film allows itself to believe that every one of the Corleones’ hits is a matter of self-defense. The other guys fired first; they tried to kill Pop and Sonny and thus are a permanent threat. Moe Greene and Barzini were colluding against the Corleones with who knows what kind of mayhem planned. The second film is revenge fantasy — it doesn’t want to believe that self-defense is necessary even though the justification is no less valid than in the first movie. Roth and Johnny Ola tried to kill Mike and used Fredo as a patsy to set it up. Pentangeli was going to put the Corleones in jail. It is the timing of Michael’s responses that feels like overkill. He’s won, as Tom Hagen declares, but his family has never seemed fully appreciative of his efforts, and he remains consumed with the idea of killing.

Vito, we finally learn late in “Part II,” succumbed once to revenge. This beautiful scene involving young Vito, Tommasino and Don Ciccio suggests one or more interpretations: That Vito would endorse revenge only because it involved an act against his mother, a civilian, or that Vito might have sworn off revenge in the first film because of what his attack on Ciccio did to Tommasino. Also this scene suggests that Michael’s actions at the end of “Part II” might have a genetic component. Both Michael and Vito have asked trusted, critical allies to do terrible things on their behalf.

Women in both “Godfather” movies are literally kept behind closed doors, emerging only when a loud argument is needed. Those arguments are considered by the other characters as nuisances. Kael writes that in the two films, “Women are so subservient they’re not considered dangerous enough to kill,” though she doesn’t see this approach as objectionable as she does in “American Graffiti.” Kael praises Talia Shire as a “stunningly controlled actress” in “Part II.” But Kael does not mention Diane Keaton’s look — one of the most haunting in cinema history — when Michael appears late in the film in a doorway. It is not the image of Michael that resonates; it is the alarm on Kay’s face as she notices his arrival.

Gaston Moschin, who plays the fading despot Fanucci, appeared a couple years earlier in Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Conformist,” which got the attention of Francis Coppola and other filmmakers. “The Conformist” is associated with fascist film aesthetics. It and “Part II” convey that while the characters all seem willing, there is more than a hint that the punishment for not going along could be as steep as death. The blowing leaves across the yard in “Part II” are said to be inspired by a courtyard scene in “The Conformist.” Where Vito had the Holy Roman Empire, Mike looks like an American Mussolini.

There is one disappointment in “Part II.” It does not affect the film but the appreciation of it. In the ending flashback, the Corleones and friends are throwing a surprise birthday party for Vito. James Caan is wonderfully present, as are Abe Vigoda and Gianni Russo. Brando is not. Francis Coppola has said in at least one interview that he tried to get Brando to appear, and apparently Brando was willing, but the scheduling didn’t work out. That Clemenza is not there could easily be overlooked (Richard Castellano declined to participate in “Part II”), but the absence of Brando in such an obvious place for him could not be conveyed any stronger if it were in all-caps subtitles: Marlon couldn’t care less.

Kael writes of one mildly weak sequence, when Michael asks his mother, in an apparent attempt by the filmmakers to remind us she’s part of the cast, how his father felt in his heart; “the question doesn’t have enough urgency.” Among “small flaws,” Kael cites “slight confusion” over Roth’s plot against Pentangeli and the “flatfooted” sequence involving Michael’s bodyguard attacking Roth and Johnny in Cuba. Kael also faults the “very poorly staged” and “gory” framing of Senator Geary and says his story is “too slackly spaced apart.”

Francis Coppola at the 1975 Oscars.

Gene Siskel, who gave ‘Part II” 3½ stars in his December 1974 review, decides that “Sequels can never be the same. It’s like being forced to go to a funeral a second time — the tears just don’t flow as easily.” Siskel knocks the many parallels to the first film and carps that “even a soap-opera writer would reject” Kay’s line to Michael about “it was an abortion; just like our marriage is an abortion.”

The “Godfather” films circumvent the quality advice that a great movie must have a great villain. The first film parades them through like a shooting gallery for episodic appeal; Sollozzo, McCluskey, Tattaglia, Fabrizio, Moe Greene, Barzini, even Carlo. The second film settles on Hyman Roth, a grand role for venerable teacher Lee Strasberg but too intellectual for maximum impact. Roth is supposed to be the last remaining Vito-era figure in Michael’s life. He will constantly inform Michael of how Vito would run things and serves as a symbol for doing things old school, the right way. But the plots against both Michael and Pentangeli are head-scratchers, and after three hours, it is still unclear whether Roth is someone to be feared or pitied.

That’s not the case for Michael Corleone. “Part II” corrects the entertainment value of the first film. The look, the confidence, the toughness and success of Michael Corleone in “Part II” eclipses Brando’s landmark work in the first film. Al Pacino doesn’t explore his scenes with cats, garden tools, shot glasses. This is what the “Sicilian thing” really does to people. For 200 minutes, we long for Michael to restore the joy of Connie’s wedding, and he fails. That is cinema’s greatest disappointment — and its greatest triumph.

4 stars

(March 2019)

(Updated September 2024)

“The Godfather: Part II” (1974)

Cast: Al Pacino

as Michael ♦

Robert Duvall

as Tom Hagen

♦

Diane Keaton

as Kay

♦

Robert De Niro

as Vito Corleone

♦

John Cazale

as Fredo Corleone

♦

Talia Shire

as Connie Corleone

♦

Lee Strasberg

as Hyman Roth

♦

Michael V. Gazzo

as Frankie Pentangeli

♦

G.D. Spradlin

as Senator Pat Geary

♦

Richard Bright

as Al Neri

♦

Gaston Moschin

as Fanucci

♦

Tom Rosqui

as Rocco Lampone

♦

B. Kirby Jr.

as Young Clemenza

♦

Frank Sivero

as Genco

♦

Francesca de Sapio

as Young Mama Corleone

♦

Morgana King

as Mama Corleone

♦

Mariana Hill

as Deanna Corleone

♦

Leopoldo Trieste

as Signor Roberto

♦

Dominic Chianese

as Johnny Ola

♦

Amerigo Tot

as Michael’s Bodyguard

♦

Troy Donahue

as Merle Johnson

♦

John Aprea

as Young Tessio ♦

Joe Spinell

as Willi Cicci

♦

Abe Vigoda

as Tessio

♦

Tere Livrano

as Theresa Hagen

♦

Gianni Russo

as Carlo

♦

Maria Carta

as Vito’s Mother

♦

Oreste Baldini

as Vito Andolini as a Boy

♦

Giuseppe Sillato

as Don Francesco

♦

Mario Cotone

as Don Tommasino

♦

James Gounaris

as Anthony Corleone

♦

Fay Spain

as Mrs. Marcia Roth ♦

Harry Dean Stanton

as F.B.I. Man #1 ♦

David Baker

as F.B.I. Man #2 ♦

Carmine Caridi

as Carmine Rosato

♦

Danny Aiello

as Tony Rosato

♦

Carmine Foresta

as Policeman

♦

Nick Discenza

as Bartender

♦

Father Joseph Medeglia

as Father Carmelo ♦

William Bowers

as Senate Committee Chairman

♦

Joe Della Sorte

as Michael’s Buttonman #1 ♦

Carmen Argenziano

as Michael’s Buttonman #2 ♦

Joe Lo Grippo

as Michael’s Buttonman #3 ♦

Ezio Flagello

as Impressario ♦

Livio Giorgi

as Tenor in ‘Senza Mamma’ ♦

Kathy Beller

as Girl in ‘Senza Mamma’ ♦

Saveria Mazzola

as Signora Colombo ♦

Tito Alba

as Cuban President ♦

Johnny Naranjo

as Cuban Translator ♦

Elda Maida

as Pentangeli’s Wife ♦

Salvatore Po

as Pentangeli’s Brother ♦

Ignazio Pappalardo

as Mosca ♦

Andrea Maugeri

as Strollo ♦

Peter LaCorte

as Signor Abbandando ♦

Vincent Coppola

as Street Vendor ♦

Peter Donat

as Questadt ♦

Tom Dahlgren

as Fred Corngold ♦

Paul B. Brown

as Senator Ream ♦

Phil Feldman

as Senator #1 ♦

Roger Corman

as Senator #2 ♦

Yvonne Coll

as Yolanda ♦

J.D. Nicols

as Attendant at Brothel ♦

Edward Van Sickle

as Ellis Island Doctor ♦

Gabria Belloni

as Ellis Island Nurse ♦

Richard Watson

as Custom Official ♦

Venancia Grangerard

as Cuban Nurse ♦

Erica Yohn

as Governess ♦

Theresa Tirelli

as Midwife

Directed by: Francis Ford Coppola

Written by: Mario Puzo

Written by: Francis Ford Coppola

Producer: Francis Ford Coppola

Co-producer: Gray Frederickson

Co-producer: Fred Roos

Associate producer: Mona Skager

Music: Nino Rota

Cinematography: Gordon Willis

Editing: Barry Malkin, Richard Marks, Peter Zinner

Casting: Jane Feinberg, Michael Fenton, Vic Ramos

Production design: Dean Tavoularis

Art direction: Angelo Graham

Set decoration: George R. Nelson

Costumes: Theadora Van Runkle

Makeup and hair: Naomi Cavin, Charles Schram, Dick Smith

Production manager: Michael S. Glick

Production supervisor, Sicilian unit: Valerio DePaolis

Unit manager, Sicilian unit: Mario Cotone

Thanks (for his special participation in this film): James Caan