The nostalgia’s hoppin’ in ‘American Graffiti,’ even if its own ending is a spoiler

“American Graffiti” is cars and songs. We see and hear them the entire movie, frankly with no letup.

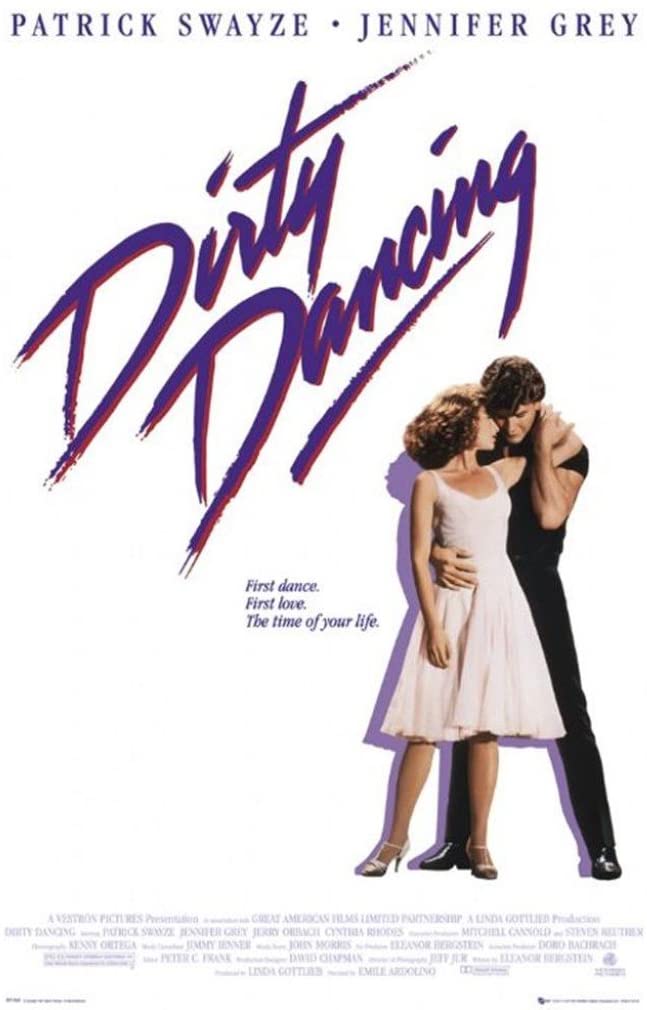

“Graffiti” is also a moment in time. A treasured moment. It’s the end of the 1950s. A lot of films (oh, “Dirty Dancing” and “Peggy Sue Got Married,” to name a couple) have embraced that notion. But “Graffiti” marks time with its rides and tunes. Sure, the events in this film occur in 1962. But everyone (and especially filmdom) knows the ’60s didn’t really begin until Nov. 22 of 1963 and didn’t really end until Watergate. A movie in 2013 about 2002 might seem like a head-scratcher. But 1973 about 1962? We all get it.

Take it from Roger Ebert. In his 1973, four-star review, Ebert writes, “I can only wonder at how unprepared we were for the loss of innocence that took place in America with the series of hammer blows beginning with the assassination of President Kennedy. The great divide was November 22, 1963, and nothing was ever the same again.”

Music changed mightily during that time. Which is why the signature moment of “American Graffiti” is one of cinema’s greatest scenes, the performance of “At the Hop” at the school dance. Think about any film with a great soundtrack. How many include a live performance? “At the Hop,” once at the vanguard of rock ’n’ roll, was only about half a decade before the Beatles and Rolling Stones, but that difference in time would soon feel like light-years. Like a 1976 computer, “At the Hop” is a rare type of enormous breakthrough quickly superseded by something bigger.

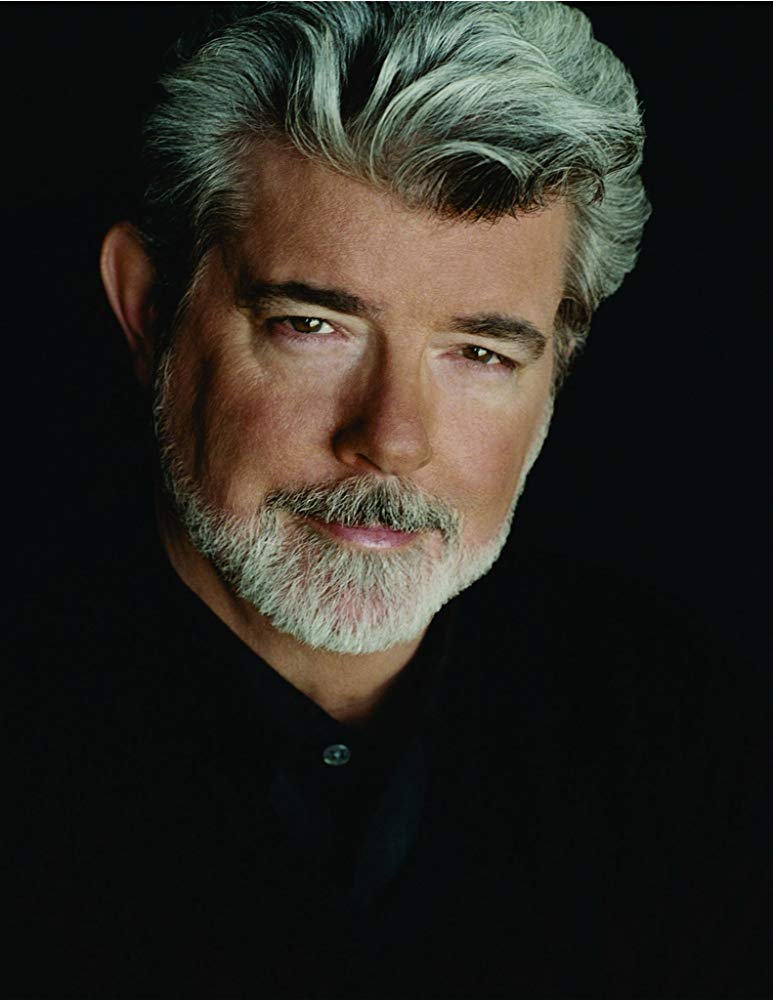

“At the Hop” ushers in the back-to-school dance around the 18-minute mark of “American Graffiti.” Like most movie songs, you will not hear it in its entirety, but fledgling director George Lucas smartly leaves enough there.

High school dance floors are social battlefields. They are places to scout for prospects and one-up rivals. Grades and athletic ability, very important at school most of the time, don’t matter here. Lucas, impressively so early in his career, recognizes this, although he doesn’t maximize his scene’s potential, opting for too much of the laborious Steve-Laurie argument. But not before crafting a little clash in which Laurie swipes her friend Peg’s date for a jealousy dance. “At the Hop” is only a portion of the dance card. The movie’s extended time on the floor runs for about 19 minutes, including cutaways to other characters not at the gym.

In “Grease” and “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” the dance is an electric moment. What’s curious about “Graffiti” is the rather humdrum atmosphere on the floor. There are apparent couples, but nobody’s hitting on anyone; that’s for the cars. The dance floor is powerful film material — music and motion — but only a routine event for the people there, who likely know each other all too well. Lucas is telling us that school dances are not like what we see in “Grease” (a film of four years later), but just like this one. Some students are energized by “At the Hop,” others bored. Some sit expressionless in the bleachers. It seems like there are twice as many girls as boys, which is perhaps common at school dances, and every girl has a perfect figure.

“Graffiti” occupies a curious niche. Movies about students in high school probably outnumber movies about students in college by as much as 10 to 1. “American Graffiti” is right on the precipice — three of the characters are recent high school graduates, two are a day away from reporting to college but are spending a night at high school with high school friends. Condensing a young person’s coming of age into one night, straddling high school and college life, is an ambitious goal, if that’s what Lucas intended; more likely, his timeline is too indecisive and contributes to the movie’s identity issues.

Lucas is recalling Modesto, actually a city of 200,000-plus, but there is a small-town look to “Graffiti.” According to Lucas, it was filmed nearly completely in Petaluma. That was a quick backup choice. The original plan was San Rafael. Part of “THX 1138” was filmed there. San Rafael in 1970 had about 39,000 people. Lucas says his crew was able to accomplish about one night of filming before San Rafael changed its collective mind and ordered them out. In a sensational community decision, Petaluma immediately proved receptive. Around the time, it had about 24,000 residents. Steve Bolander will refer to the area as a “turkey town.” San Rafael, Lucas says, did allow them to come back for a few extra shots. The Rafael Theatre with angled marquee is famously visible in the movie. Petaluma has an even greater claim to filmdom fame — it’s the birthplace of Pauline Kael.

The scene is not as stark as the depiction in “The Last Picture Show,” also a retro success from a couple years before “Graffiti.” “The Last Picture Show” dealt heavily in sexual themes while “Graffiti” is preoccupied with love. The “Graffiti” kids have it better than those in “Picture Show,” they have things, including nice cars and Vespa scooters. What they don’t have is aspiration. Underlying the music and the cars is the idea of settling, which exerts on these characters and just about every person in general the pull of a tractor beam, a powerful weapon in a later George Lucas movie. Steve is not settling — at first. He demonstrates this by initiating a conversation at the beginning of the film that he doesn’t need to be having for weeks or months. Is he really not so confident, is his suggestion his own test to see where he stands? Toad and Milner are settling. Curt is where the drama is. There is little wealth here, and worst of all, maybe nothing to do, except listen to Wolfman Jack. The community is a middle-class trap — higher floor, lower ceiling.

The amount of students at this school can probably be explained by social scientists based on the attendance at the dance. Maybe about 500 total students? Not a small school, but not huge. This is not end of the year, when people tire of each other and move on, but a back-to-school event where people seem jaded. Is everyone dreading the fall semester ... or is Lucas quietly implying that the ’50s motifs, in 1962, were becoming passé.

Movies are pop culture, sometimes beautifully married to it. One of the girls at the dance is Kathleen Quinlan, who would receive her first film credit in “Graffiti.” She will stick her tongue out a few times (Mackenzie Phillips will do this also), perhaps something like the way the male cast members often stuff their hands in their pockets. Casting chief Fred Roos, a “Godfather” figure, says he had heard of the great drama program at Tamalpais High School, where the dance scene is actually shot. Roos called the school’s famed teacher, Dan Caldwell, and asked for a couple recommendations. He got the name of Quinlan, who thought she was participating in a “cattle call” but instead met Francis Coppola and Lucas and was asked to read a small part. One wonders about the joy of Quinlan’s role coming to fruition, launching a decadeslong Hollywood career that would later include an Oscar nomination. Her unfolding real life is the most exciting 18-year-old’s story here. She was a competitive gymnast then with “no intention” of pursuing an acting career, then this chance event. Did she go to theaters to see “American Graffiti” with crowds (like the Sharon Tate character in “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood”) and enjoy telling friends and others about being in this blockbuster? Did she already have an agent, did she get one immediately after, did the calls start piling up before the movie’s release or after? Hopefully, it has been the real-life fairy tale that it seems.

Undoubtedly, the movie’s biggest discovery is Harrison Ford. Roos says Ford at that point was into his famous carpentry career, including working at Roos’ home, and that Roos talked him into doing another film. It seems obvious in hindsight that Ford should’ve been John Milner and that Paul Le Mat, who put together a nice career of his own, including in the cult favorite “Melvin and Howard,” be the bad guy in town, but sometimes, you never know.

For his live band, Lucas chose Flash Cadillac and the Continental Kids, a retro band of the time. Though a sensational choice, he could’ve tapped the real thing. Danny & the Juniors, who made “At the Hop” a 1957 hit, were still out there, as were many others such as The Beach Boys, any of whom could’ve played this high school under a local-sounding name, but perhaps Lucas didn’t want older musicians, or perhaps he just liked the look of Flash, or perhaps the others wouldn’t have fit in the budget. Another song at the dance, Flash’s own “She’s So Fine,” perfectly hits the spot.

On a couple important levels, “Graffiti” is a big miss. It is, like Lucas’ other works, mechanical. There is more drama in the ending text updates than in the whole rest of the movie. Lucas explained that this was his idea against the advice of his co-writers. (Possible setup for a sequel, which was praised by Ebert, but it flopped.) For a few moments, they function as an In Memoriam feature in a tragedy, as if the flight buzzing faintly in the background is going to have a devastating conclusion. (A very subtle nod to rock ’n roll tragedies, possibly?) Notice which names are posted first. Then a bouncy Beach Boys song kicks in.

Maybe the bigger issue isn’t what that text tells the audience, but the actors. Ron Howard says the ending description “definitely informed” his performance. Directors may pause at going down such a path, telling actors how the director envisions the character years after the film ends. Some movies, often ones about real-life people and events, do conclude with updates. There is something about this one that feels cheap and unearned. If the previous 110 minutes have not conveyed to us where these characters will be in a couple of years — not precisely the arbitrary outcomes that Lucas lists, but in general — we have a partial fail. (The wimpy klutz is the one who ends up in Vietnam; bad luck always finds Terry.) It is also a statement about who matters and who doesn’t in this ensemble. Pauline Kael complains that the ending description “ignores the women characters.” Lucas says “for creative reasons,” he declined to include the women characters; it would have been “two cards ... twice as long” and in that instance, “kind of disrupts” the ending. Cindy Williams says the decision “smacked of the times.”

Ironically, Lucas apparently seemed to think he was unleashing some kind of feel-good story. He told Gene Siskel in 1980 that after his “THX 1138” struggled commercially, “I was getting bugged by Francis (Coppola) and some other friends who said that the movies I made were too cold, too artsy, that they dealt with theme rather than plot. They said, ‘Why don’t you make a regular movie that’s warm and funny and has a plot?’ ” But “Graffiti” isn’t warm, and it’s not that funny. Lucas told Siskel that “Graffiti” was “just a document of the mating rituals of contemporary American youth.” In fact, “cold,” “artsy” and “theme” are accurate criticism of “Graffiti,” even as its sum-of-the-parts successes are among history’s most impressive.

Most “Graffiti” characters’ stories are not visual, and frankly not very interesting. Everything must be relayed to the viewer via arguments and debates. Whether any of the boys ends up with any of the girls doesn’t really matter. But there’s a pioneering spirit.

On this night, Lucas sets off each of the four males in pursuit of a girlfriend fantasy. The contrasts intrigue. Curt has had dates (we meet one, who remains interested), but he’s bored by them; he’s only excited by the goddess he sees in a Thunderbird, and the rest of his night is about a chase. Steve wants the all-clear to explore, a reassurance that if he doesn’t find something better at Middlebury, she’ll still be here for him. His night is about winning an argument. Toad is desperate for anyone and can’t believe he finds an attractive woman all alone while he’s got a hot car; this evening, he will tell more lies than maybe any movie character. Milner’s story is the most visual — he is quickly learning he’s too old for cruising, and it’s breaking his heart. None of the eligible girls wants to ride with him. They prank him instead.

Probably few movies before “Graffiti” separated casts into individual drama settings, only briefly in this work interacting at a stop light or parking lot. True, it happened/happens in disaster movies and a few adventure movies, but those characters in the end are all confined to the same airplane/boat/skyscraper in a life-or-death struggle.

The disaster at the end of “Graffiti” is an explosive car accident that somehow everyone escapes with barely a scratch (and apparently the police, who watch everything else like a hawk, fail to notice). It’s a metaphor not for physical danger but emotional stunting, as characters realize maybe they shouldn’t be long for this kind of scene anymore.

However imaginative, Lucas doesn’t quite close the deal, and “American Graffiti” will too often seem episodic. In a “making of” documentary on the DVD (copyright 1999) that is the source of much of the crew’s commentary on this page, Lucas says “it was one of the first movies to ever tell four stories simultaneously and have the four stories not really be connected with each other. The studios said that was impossible, ‘You can’t do that.’ ” Limited to two hours, those personal dramas are ambitious but reduced to a lot of soundbites. Later, this concept of barely interlocking storylines would become an aspiration of several elite filmmakers, in films such as “Nashville” and “Babel” and “Magnolia.”

Lucas says “Graffiti” in 1973 was “a very avant-garde movie.” Pauline Kael, one of the guardians of such distinctions at that time, didn’t use that term, calling the film a “warm, nice, draggy comedy.”

Back in 1975, Roger Ebert reported on a Chicago speech by Kael, who was talking about movie nostalgia. “A movie like ‘American Graffiti’ was such a tremendous hit because it hit that age group right on the nose. It was set in the years when they were going to high school, and they responded to it so strongly they didn’t quite see some of the things wrong with it,” Kael said.

The drama in “Graffiti” that does resonate is the notion of people who are beyond high school age trying as hard as possible to remain teenagers. You won’t really get that feeling from the Steve character of Ron Howard (who has second billing, after Richard Dreyfuss, who was generally called “Rick” by others on the production), nor his sorta-steady girlfriend Laurie, but you will from the rest of the cast. The older characters, the hot-rodder John Milner (named after Hollywood legend John Milius, Lucas says) and the hood leader Joe and the school dance chief, Mr. Wolfe, are grownups who find themselves spending weekend nights with high school kids. Like “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” and many other teen movies, the characters’ parents are essentially out of the picture. Being a virtual adult when you can cruise the streets and hop into whatever car had the prettiest girl you’ve seen in a week has great appeal. “In its best moments,” writes Gene Siskel in his 1973 review, “it is about being teenage.” If Quentin Tarantino has specialized in the 40-something fearing that his/her best days are in the past, “Graffiti” seems to think 19-year-olds might have similar issues.

Why are last spring’s graduates attending the back-to-school dance? Steve must, because Laurie is a current senior. Curt shows up apparently in search of guidance, or maybe he just has nothing to do the night before a big flight. By chance, Mr. Wolfe, maybe still a twentysomething but who looks at least 35, pulls Curt aside. It seems Mr. Wolfe is eager for some instant therapy on his own decision to abandon an East Coast college and that he senses Curt is someone who “gets it.” Mr. Wolfe fairly recently did just what Curt has been preparing to do, only to come back to his hometown after just a semester, realizing he “wasn’t the competitive type.”

Going to college ... the drama hook of “Graffiti” ... is a curious subject for Lucas. From several biographical accounts, there is no doubt Lucas was a very bright and curious youngster. He was interested in a career racing cars, but he was badly injured in an accident just before high school graduation. Academics? He was interviewed at his Bay Area home in 1980 by Gene Siskel, who wrote that Lucas somehow got “mostly D’s” in high school. Nevertheless, Lucas gave junior college a try and took an interest in anthropology, a subject he mentions when discussing “Graffiti.”

His ticket to the big time came with his enrollment at USC film school — according to Siskel, a friend who attended USC recommended Lucas go there. Nowadays it sounds impossible for someone of Lucas’ academic background to get into USC film school, but this was the 1960s. Lucas mentions that Haskell Wexler, the famed photographer who worked on “Graffiti,” helped him get in. Surely what he learned at USC proved important, but likely more important was the people he met there, at a time when upstarts were taking over Hollywood. Lucas is one of the reasons those upstarts took over. “Graffiti” seems to be far more neutral than Lucas’ life story on whether going to college is the right move.

George Lucas at the 1974 Oscars.

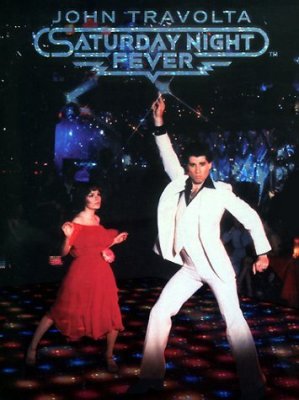

Lucas is trying to make a point, as some movies do, about geography — the East is the way out; otherwise, you’re John Milner. But talking about East Coast colleges isn’t nearly as effective as, say, Tony Manero in Bay Ridge making a trip to Manhattan and becoming seduced in “Saturday Night Fever.” And really, what’s wrong with the Modesto geography? There are pretty girls everywhere. It’s a clean town with lots of businesses, and most of the adults in the movie are even kinda hip. San Francisco and Sacramento are each less than a hundred miles away. “Graffiti,” despite its stated intentions, is far less about geography than class. It’s trying to say that if you stay in town, you’ll end up with the Milners and the Pharoahs. But it actually bears parallels to “Good Will Hunting,” the character who should be challenging professors but gravitates to the comfort level of his bricklaying friends and finds the choice difficult.

In an interesting flip from “Graffiti,” the courtships in “Saturday Night Fever” occur on the dance floor, not the cars, because hardly anyone in that film owns one. The one guy in “Fever” with a car, Bobby C, is much like the Charles Martin Smith character in “Graffiti.” Both are picked on; they are the bully targets. Bullying is an interesting emphasis by Lucas. Toad gets pantsed in the opening minutes, actually while asking a woman out on a date, and everyone laughs. The movie makes the argument from its earliest scenes that Toad deserves the reactions he gets. He’s a klutz, not particularly smart, not socially adept, but for whatever reason has connections to the cool kids. “American Graffiti” and “Back to the Future” assert that bullying was an acceptable rite of passage in the ’50s. Maybe Lucas was on the receiving end of some of it, or maybe he witnessed it, or maybe he just thinks it adds to his characters. Nowadays, people who get mooned can sue. Maybe school decorum truly was different in the ’70s, a change for the better.

Despite Roger Ebert’s recall, “Graffiti” will demonstrate that the ’50s weren’t as innocent as popular sitcoms suggested. That theme has been seized by numerous films — let’s face it, every movie about the ’50s since the ’50s makes that point — but give “Graffiti” credit, it had to be one of the first. The hijinks in the film aren’t particularly traumatizing. Underage drinking, vending machine burglaries, drag racing, vandalizing police cars (that last one would be more controversial if the officers weren’t portrayed as crusty killjoys). Even “Grease” had an apparent pregnancy. (“Graffiti,” however, does not take any risks with language.) Ebert wasn’t seeing any counter-“Leave it to Beaver” themes. “The radio was on every waking moment,” Ebert writes. “The music was as innocent as the time ... nothing prepared us for the decadence and the aggression of rock only a handful of years later.”

A 1973 ad for “American Graffiti” in the Chicago Tribune.

No doubt, the ’50s and early ’60s were powerful nostalgia in 1973 and still today. Thirtysomethings and some twentysomethings of the early ’70s could easily recall a much less controversial world than the one in which “Graffiti” was released. That’s probably why young adults flocked to theaters to see it. “Graffiti” grossed $115 million, a staggering haul for the time, especially for a movie made for reportedly less than $1 million, although the two big budget movies that topped it in 1973, “The Exorcist” and “The Sting,” crushed it with $193 million and $159 million. Lucas says in the making-of-“Graffiti” documentary that “the return on the dollar spent is I think greater than almost any other movie made.”

The filmmakers note that the song rights for this movie were acquired on the cheap, allowing such a high return on the dollar. Different times then, copyright holders of 1950s and ’60s work were probably in the early 1970s just glad that someone was still interested. Another bit of genius was casting so many legendary actors who had mostly yet to be discovered and thus were affordable. That is more of a credit to the film’s legacy than its bottom line, as filmgoers in 1973 went to see this one not having any clue that Harrison Ford was actually a big deal.

Roger Ebert was born in 1942. His future TV partner, Gene Siskel, was born four years later and didn’t appreciate the “Graffiti” era as much as Ebert. Twice in his review he refers to characters and settings as “too pat,” and unlike Ebert, he noticed the film’s absence of diversity. “There is no question that this movie is about the teen-age lives of white California kids,” Siskel writes.

“It also is a man’s movie,” he writes. “The girls are there only because the boys want them there.” That was a reaction seconded by Pauline Kael. “For women the end of the picture is a cold snap,” Kael writes in 1973, also questioning whom the movie’s memories are for. “Not for women, not for blacks or Orientals or Puerto Ricans, not for homosexuals, not for the poor. Only for white middle-class boys whose memories have turned into pop.”

Kael nevertheless writes “I like the look of ‘American Graffiti,’ and the feel of it” and that George Lucas “has a sensual understanding of film” and is a “real filmmaker.”

Cast members repeatedly mention Lucas’ use of flawed takes. He liked the authenticity. This hints at a greater truth about acting, that all the training in the world can’t supersede an instinctual reaction. Charles Martin Smith notes that he wasn’t supposed to run the Vespa into a curb. Lucas appreciated the authenticity of that sudden mishap, and it became a memorable opening scene.

“American Graffiti” is not the only film to limit its portrayal to a single day. But this isn’t daytime. Actors note that they were filming the movie all night and trying, often unsuccessfully, to sleep during the day. But what about the audience? A movie taking place almost entirely at night is a tough sell. In many movies, the setbacks happen when it’s dark out. Audiences are prone to expect bad things or scary things at night. There are in fact numerous crimes or infractions or fights depicted in “Graffiti,” but each with some grain of humor, and this is Lucas’ geography point again that is just as important, if not as unique, as his observations about music and cruising and teenagerdom — that there’s no future in this town, that its bored citizens have nothing to do but prank and one-up each other, that this is how the whole community entertains itself at night.

Some of these scenes are a reach. Terry will drive up in front of a used-car lot to inspect his own car, and there will somehow be a man sitting on a gigantic rocking chair in suit and tie immediately waiting to sell Terry, or anyone, a car at this hour. (Evidently, the rocking chair was a real thing that Lucas had seen somewhere.) Another time, Terry will try to illegally buy liquor at the same time a man is trying to rob the store.

Lucas, though, helped by his “visual consultant,” the great Haskell Wexler, got creative. In the making-of documentary, it is noted how the music often sounds like how the characters are hearing it, not as the audience would. To save time during filming, Lucas put cameras between cruising cars and shot both sides of the conversation at once.

There was genius in the title. “American Graffiti” is one of the greatest. Lucas wouldn’t budge. Francis Coppola says that the marketing team thought the audience might “think it’s a movie about feet.” Coppola admits he didn’t agree with Lucas’ choice and suggested coming up with “any kind of dumb name.” A lot of films with lofty aspirations put “American” in the title. Try finding any before 1973. Lucas wasn’t making a description, but a statement.

One of the more visual dramas occurs when Curt is caught with the hoods at the arcade by the old-school businessman. Lucas gives Curt a dilemma. This is the moment of truth: Is he going to be a rebel, or is he going to be the Establishment, which has already helped him out. It’s a little bit like Danny Noonan in “Caddyshack,” though Danny’s not under duress and the people in “Graffiti” are all playing it straight. Curt will try to straddle the situation before making his decision, under just enough pressure to cause viewers to accept his actions. It seems hard to believe that after Curt cuts the bad guys a huge break, they come back into the shop to tell him to rejoin them, but Curt’s exploration won’t be finished until later in the morning.

Not only did the box office smile on “Graffiti,” but so did the Academy Awards, which gave it five Oscar nominations, including the heavyweight categories of Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay and Best Editing. It did not win — its competition included “The Sting,” “The Exorcist” and “Cries and Whispers.” The curious “Graffiti” nominee is Candy Clark for Best Supporting Actress. That category has produced maybe the most jaw-droppers over time, but Clark’s honor is not an outrage. She probably had little chance against Tatum O’Neal (the winner) and Linda Blair.

For whatever reason, Roger Ebert, despite his initial four-star review, did not include “American Graffiti” in his Great Movies portal, despite the fact “Graffiti” elicited more initial gushing from him than many other films of that distinction. Maybe the impact on him faded over time. About a half-dozen years after the great success of “Graffiti,” Lucas and nearly all of the main original cast tried again with “More American Graffiti.” Lucas, white-hot off of “Star Wars,” didn’t direct this time. The result failed to re-catch lightning in a bottle, was panned and probably barely made money. Sometimes a movie is perfect for its time. Sometimes not.

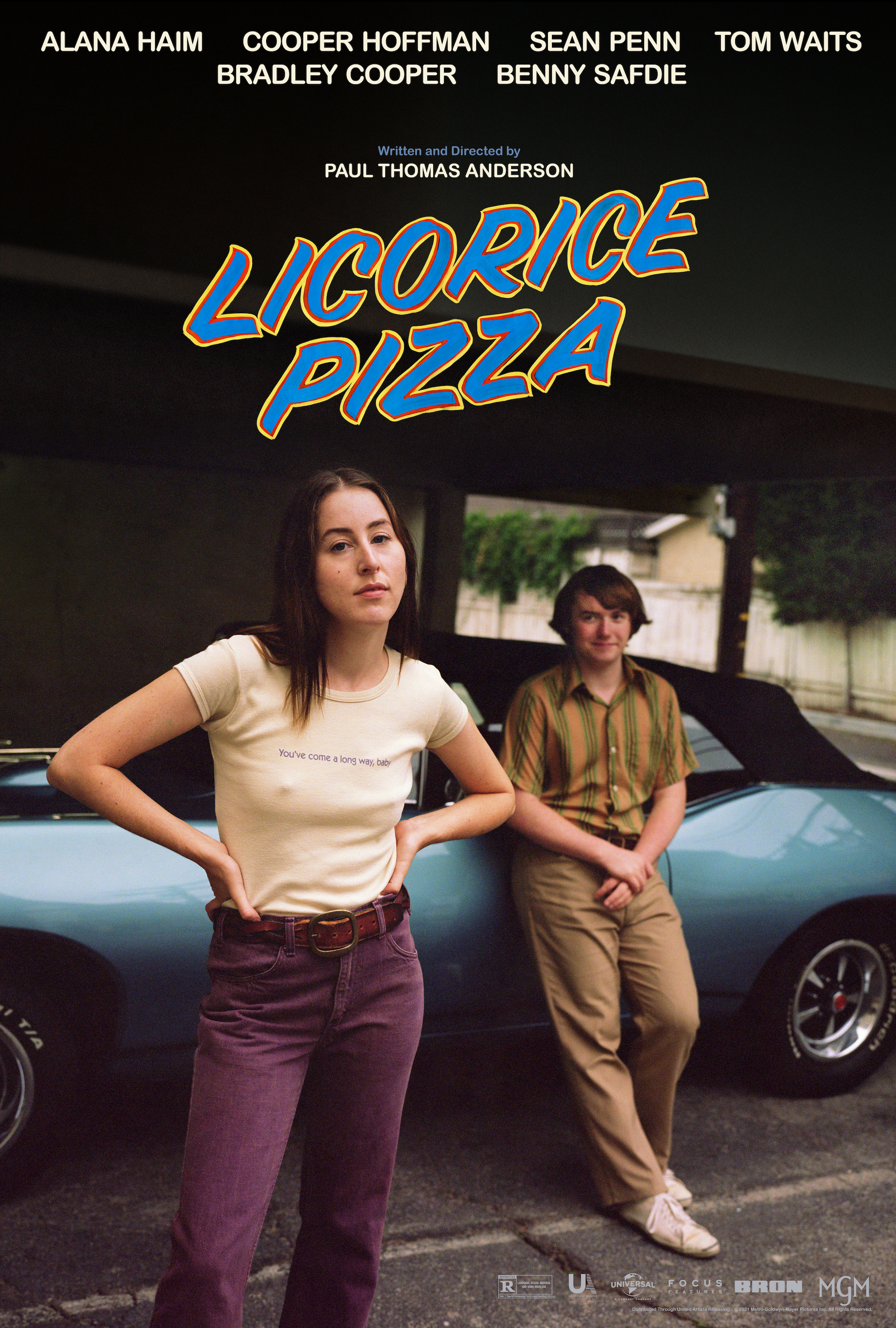

“American Graffiti” achieved an instant stature — it’s the movie Sid Caesar is trying to watch during the beleaguered flight in “Airport 1975.” (Both films are Universal Pictures, which makes usage like that possible.) But “Graffiti” left its mark on more than Ebert’s generation. There are subtle tributes to it in Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Licorice Pizza” of 2021, which includes a school toilet explosion and the same green opening credit font. “American Graffiti” and “Licorice Pizza” are part of the narrow, appealing genre that also includes “Almost Famous” and “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” atmospheric films in which the auteurs share warm memories of childhood through cars, music, movie marquees and pop culture. Maybe the episodes don’t really add up and maybe they searched a little too hard to fill those script pages with drama. And that’s OK.

3.5 stars

(August 2023)

(Updated July 2024)

(Updated September 2025)

“American Graffiti” (1973)

Cast:

Richard Dreyfuss

as Curt

♦

Ronny Howard

as Steve

♦

Paul Le Mat

as John

♦

Charlie Martin Smith

as Terry

♦

Cindy Williams

as Laurie

♦

Candy Clark

as Debbie

♦

Mackenzie Phillips

as Carol

♦

Wolfman Jack

as Disc Jockey

♦

Bo Hopkins

as Joe

♦

Manuel Padilla Jr.

as Carlos

♦

Beau Gentry

as Ants

♦

Harrison Ford

as Bob Falfa

♦

Jim Bohan

as Holstein

♦

Jana Bellan

as Budda

♦

Deby Celiz

as Wendy

♦

Lynne Marie Stewart

as Bobbie

♦

Terry McGovern

as Mr. Wolfe

♦

Kathy Quinlan

as Peg

♦

Tim Crowley

as Eddie

♦

Scott Beach

as Mr. Gordon

♦

John Brent

as Car Salesman

♦

Gordon Analla

as Bozo

♦

John Bracci

as Station Attendant

♦

Jody Carlson

as Girl in Studebaker

♦

Del Close

as Man at Bar (Guy)

♦

Charles Dorsett

as Man at Accident

♦

Stephen Knox

as Kid at Accident

♦

Joe Miksak

as Man at Liquor Store

♦

George Meyer

as Bum at Liquor Store

♦

James Cranna

as Thief

♦

Johnny Weissmuller Jr.

as Badass #1

♦

William Niven

as Clerk at Liquor Store

♦

Al Nalbandian

as Hank

♦

Bob Pasaak

as Dale

♦

Chris Pray

as Al

♦

Susan Richardson

as Judy

♦

Fred Ross

as Ferber

♦

Jan Dunn

as Old Woman

♦

Charlie Murphy

as Old Man

♦

Ed Greenberg

as Kip

♦

Lisa Herman

as Girl in Dodge

♦

Irving Israel

as Mr. Kroot

♦

Kay Ann Kemper

as Jane

♦

Caprice Schmidt

as Announcer at Dance

♦

Joe Spano

as Vic

♦

Debralee Scott

as Falfa’s Girl

♦

Ron Vincent

as Jeff

♦

Donna Wehr

as Carhop

♦

Cam Whitman

as Balloon Girl

♦

Jan Wilson

as Girl at Dance

♦

Suzanne Somers

as Blonde in T-Bird

♦

Flash Cadillac and the Continental Kids

as Herby & the Heartbeats

Directed by: George Lucas

Written by: George Lucas

Written by: Gloria Katz & Willard Huyck

Producer: Francis Ford Coppola

Co-producer: Gary Kurtz

Cinematography: Jan D’Alquen, Ron Eveslage

Editing: Verna Fields, Marcia Lucas

Casting: Mike Fenton, Fred Roos

Art direction: Dennis Clark

Set decoration: Douglas Freeman, Paul Nickerson

Costumes: Aggie Guerard Rodgers

Makeup and hair: Betty Iverson, Gerry Leetch

Production manager: Jim Hogan

Visual consultant: Haskell Wexler

Thanks: Oscar Hammerstein II, Richard Rodgers