Marion Cotillard at the 2008 Oscars.

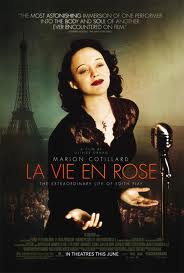

Marion Cotillard’s ‘La Vie en Rose’ is exhilarating, exhausting, extraordinary

Probably no movie genre boasts as many busts as the biopic.

So when a biopic is actually good, it’s a cause for celebration.

“La Vie en Rose,” the story of Edith Piaf, is a very rare musical biography — it’s not about what you’re hearing, but seeing.

Director Olivier Dahan says in DVD commentary, “I wanted to make a film about how an artist functions in the world.” Alas, that alone is not a movie. Marion Cotillard says the film is “the private story of a great artist ... Her life was filled with great joy and profound misfortune.” Once again, there has to be more.

There is. Most musical tragedies involve death. This one is about decline. How in the world can a human being, especially one this wealthy and famous, stoop to this level? That is a pun intended. Cotillard in Piaf’s final years elicits a devastating respect for this tiny powerhouse and pity for her condition. The more beautiful her environment gets, the more decrepit Edith gets. Providing joy to others, rather than invigorating her own life, wipes her out.

Rightly known as a majestic work of Cotillard, the world’s premier actress, “Rose” is a spectacular partnership. Cotillard says in DVD commentary that she and Dahan easily connected over the subject and even conversed about Piaf, whose name, a stage title, means sparrow, as “fans” rather than filmmakers. Played straight, Cotillard’s Piaf would be a run-of-the-mill candidate for awards season. Blessed with Dahan’s gamble, “Rose” is a landmark work that has to be included among the finest of this still-young century.

“Rose” includes no guns. But somehow, it often looks like an American Western. There are bars and brothels. Piaf was born in 1915, when horses were still a crucial ingredient for getting from Point A to Point B, when struggling people had to make a go of it on the streets, when prostitution might be required to pay the rent. Oddly, but refreshingly, the film dismisses any impact of wars on Edith’s life. A lot of the earlier scenes have the feel of European wartime, people picking up the pieces, but Edith’s battles are internal.

Dahan and cinematographer Tetsuo Nagata splash their scenes with beautiful colors, then reduce the contrast to such level that blackness typically surrounds the characters. We see that Edith has filled her audiences with light while unable to sustain it herself. In a 1963 scene early in film, Edith will tell an assistant, “I prefer it dark,” a comment of significant subtext. Dahan will take us through halls of bordellos, cabarets and hotel suites, showing us something unmistakably nocturnal about this person. Gradually the bars and brothels transition to exquisite restaurants and plush auditoriums, and Edith will become less and less comfortable. In the rare moments when she relaxes, there will be beautiful shots of a beach, a fine restaurant, a late-night diner.

The more controversial decision is Dahan’s structure of an out-of-order timeline. A.O. “Tony” Scott of The New York Times calls the flashbacks “a complete mess.” That may be true upon first viewing for those with formula in mind. Watch it more than once, and you get the point — trouble managed to find this person, at every age. It doesn’t matter whether others were calling the shots or she was calling the shots. There is perhaps a touch of Baz Luhrmann here. Don’t try to piece together the timeline; let the film tell you what it’s trying to say. Dahan will save an unexpected, explosive flashback for the end, not unlike the depiction in “The Godfather: Part II” of Michael being chastised by Sonny for enlisting in the Marines. Where Michael was being better than his parents, Edith Piaf was finding herself no different.

“La Vie en Rose” is a term that is culturally significant. Roger Ebert says the meaning “translates loosely as ‘life through rose-colored glasses.’ ” The film is called “La Môme,” literally meaning “The Kid,” in France. It reminds us that life chooses superstars randomly. While some elites are born into it — Michael Douglas, Ken Griffey Jr., John F. Kennedy — many others come from the most unassuming or humble circumstances, and we cannot escape those roots, the genes we inherit and the communities that shaped us, however pleasant or unpleasant. Prince William and Prince Harry were groomed to be royals from birth, but did anyone know when Mickey Mantle was 10 in tiny Commerce, Okla., that he would be the last (unofficial) Chairman of the Board of sports’ greatest dynasty in America’s largest city? Of course not.

A typical biopic will open by teasing at a signature moment in the character’s career, then take us back to the beginning and slowly get us back to the top. Notice that “Rose” opens with a collapse; the ending is a triumph. There is perhaps a very simple, and not very Hollywood-ish, answer for this: that our health goes a long way toward determining our happiness. If an artist takes pills because of pressure, that might be a movie. If she takes pills because of arthritis, that is a non-starter. But an incipient health risk that no one acknowledges is fatigue. For those who suffer greatly, medication can’t stop the merry-go-round and (this isn’t the first movie with this suggestion) only makes it worse. This is what Dahan and Cotillard are telling us.

Perhaps even more remarkable than her voice is Piaf’s posture. This is a mega-successful human being who at 47 somehow looked 87. Was that artistic embellishment? Roger Ebert says no, “Even the hair is right; her frizzled, dyed, thinning hair in the final scenes matches the real Piaf.” Cotillard recognizes something extraordinary, that the way this person looks and moves tells us what we need to know. Her toothy grin puts people at ease in her presence and hints at her performance charm, until gradually, the grin makes her look more and more unhinged, unsure of herself. Often she will prepare to perform with a look, “Should I really be doing this?” Never does Cotillard nor her sensational makeup crew betray her character by allowing Cotillard’s staggering beauty to encroach. Every movie has beautiful people. This is a movie of acting. Cotillard mostly leaves the singing to Piaf; a sequence in which she performs without sound is one of the most beautiful of any musical biopic. Piaf looks even more stooped than Bruno Ganz’s Hitler, who was 9 years older in his final hours as Allied forces came to collect him in “Downfall.” Marion Cotillard’s height, according to a prominent critic, is 5-feet-6, while Piaf was 4-feet-8. In a 2014 interview, Cotillard indicates the role haunted her after filming: “I would go to a dinner and before arriving, I would realize that it was close to where she had lived. Always, things like that. I felt connected to her in a way that was not healthy for me.”

Usually, biopics will depict a star either relying on someone with ulterior motives or pushing away those who genuinely want to help. “Rose” suggests that neither was Piaf’s problem. Nor did she have to deal with clingy relatives. The people around her were decent; she didn’t fight them on anything substantive. Cotillard channels Piaf in moments as very strong, someone who commands attention and respect from those around her, while astoundingly vulnerable. It seems anyone who wanted to could take her down a notch; this was hardly a person of Teflon. It doesn’t seem anyone took advantage of her nor that she made diva-like demands. Her greatest smiles are in the presence of Marcel, a lover and champion boxer whose offscreen fate is beautifully depicted. Her cheers for him are her most vibrant moments in the film.

Circuses were a fascination of Fellini and Bergman. They depicted performers, especially in Bergman’s masterwork “Sawdust and Tinsel,” as the lowest class of entertainment, people who loved their own work despite the transient and sometimes-humiliating nature of it. Dahan seems equally intrigued, illustrating that Edith’s father is an acrobat reduced to street performing reduced to forcing his daughter to do something ... anything to keep the temporary crowd from withering away.

From one of these scenes, the unfortunately necessary but powerful cliché is delivered: Edith must go from a nobody to a somebody, and she does this at a young age when her father demands she perform on the street and she sings “La Marseillaise,” and people stop and listen. This is almost a frightening scene. Would dad get rid of her (again) if she couldn’t help him out? We’ll never know. But Dahan will water down this moment, requiring an older Edith to be heard, in a bit of a fluke, by a nightclub boss before anyone really cares who she is.

As Edith ages, we see exactly what her father left her — the genes of a clown. She will gradually resemble the Joker, whose hair is actually green, not orange, and these scenes, strategically inserted in later stages of the film, are the saddest, almost a reverse parallel to “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.”

In “Scarface,” Tony Montana will inform a woman, “I come from the gutter.” For many movie characters, this is a source of strength. “Rose” is an outlier, suggesting that Edith’s upbringing in the school of hard knocks has only battered her psyche and takes its toll gradually, with accelerating momentum. Once earning a living in raucous cabaret settings, she’s unable to sing to suits. Did she ever try analysis? It seems such counseling was beyond not her pay grade but status grade.

Cotillard doesn’t make a distinction, but “Rose” illustrates the difference between someone like Piaf and someone like Van Gogh. One can toil in silence, the other has to toil in front of the bourgeoisie.

Despite its emphasis on artistry, “Rose” is forced to indulge in the business of moviemaking. Tony Scott of the New York Times notes in the first sentence of his review that the movie is cognizant of the U.S. filmgoing audience. “Rose” is a French film but an international one, and the biggest potential market, the marginal dollars that can bring a jackpot, of course is in the Western Hemisphere. That is probably why we see very forgettable scenes of Piaf in New York and (especially) California, hearing from advisers that Americans aren’t all that impressed with her work and then, more or less, returning the favor. “Rose” strongly implies — by telling, not showing — that popular music, for whatever reason, is a bordered phenomenon, that singing appeal is constrained by nationality. Dahan apparently wants American filmgoers to know that Edith tried, so perhaps they should, too.

Cotillard came up big at the Oscars, winning the Academy Award for best actress, a rarity for a foreign film and the only such honor for a French work. With the award came international acclaim. She defeated Cate Blanchett (“Elizabeth: The Golden Age”), Julie Christie (“Away from Her”), Laura Linney (“The Savages”) and Ellen Page (“Juno”). But “Rose” also picked up an Oscar for best achievement in makeup, a limited but important category, besting “Norbit” and “Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End.”

Roger Ebert bestowed 4 stars on “Rose,” calling it “one of the best biopics I’ve seen.” Peter Travers found it “a performance for the ages.” Others weren’t as moved. Richard Roeper, according to Rotten Tomatoes, called it “a surreal and exhausting experience.” Michael Phillips decided it is “wildly uneven.” Richard Schickel decreed it “simple-minded, cheaply sentimental and unrelievedly lugubrious.”

Do Americans appreciate the Piaf story? She’s more pervasive than you might think. In 2018’s Oscar front-runner, “A Star is Born,” Lady Gaga sings “La Vie en Rose” at a trans bar. Several reviewers liken the Piaf story to that of Judy Garland, who also died at 47 but whose downfall has yet to inspire a memorable film.

Biopics have gotten a bad name. Just a few of the appalling efforts of recent years are “Steve Jobs,” “Molly’s Game” and “J. Edgar.” And there’s a subgenre of material that is sort of biopic, sort of not, such as 2018’s “Can You Ever Forgive Me?” and “Green Book.” Don’t forget, there is also “Citizen Kane.” “La Vie en Rose” is the real deal.

Is “La Vie en Rose” an argument for or against the welfare state? It depends on whether you find Edith Piaf’s discovery a fluke. Nowadays, society’s answer for young Edith is to place her in a foster home and ensure a formal education. She would’ve avoided the fast lane of indulgence and perhaps would’ve found satisfaction in healthier ways and lived much longer. In that scenario, she probably would have been more classically trained. She would not have been noticed by nightclub moguls on street corners and never earned the crown of “the soul of Paris.” “Rose” hints that when our backs are against the wall, we make things happen, sometimes things that are so good, they’re beyond our control.

4 stars

(December 2018)

“La Vie en Rose” (2007)

Starring Marion Cotillard

as Edith Piaf ♦

Sylvie Testud

as Mômone ♦

Pascal Greggory

as Louis Barrier ♦

Emmanuelle Seigner

as Titine ♦

Jean-Paul Rouve

as Louis Gassion ♦

Gérard Depardieu

as Louis Leplée ♦

Clotilde Courau

as Anetta ♦

Jean-Pierre Martins

as Marcel Cerdan ♦

Catherine Allégret

as Louise ♦

Marc Barbé

as Raymond Asso ♦

Caroline Silhol

as Marlene Dietrich ♦

Manon Chevallier

as Edith - 5 years old ♦

Pauline Burlet

as Edith - 10 years old ♦

Elisabeth Commelin

as Danielle Bonel ♦

Marc Gannot

as Marc Bonel ♦

Caroline Raynaud

as Ginou ♦

Marie-Armelle Deguy

as Marguerite Monnot ♦

Valérie Moreau

as Jeanne ♦

Jean-Paul Muel

as Bruno Coquatrix ♦

André Penvern

as Jacques Canetti ♦

Mario Hacquard

as Charles Dumont ♦

Aubert Fenoy

as Michel Emer ♦

Félix Belleau

as Robert Juel ♦

Ashley Wanninger

as Leplée’s assistant ♦

Nathalie Dorval

as Mireille ♦

Chantal Bronner

as Josette ♦

Cylia Malki

as Philipo ♦

Nathalie Dahan

as Yvonne ♦

Laurent Olmedo

as Jacques Pills ♦

Harry Hadden-Paton

as Doug Davis ♦

Laurent Schilling

as Claude ♦

Dominique Bettenfeld

as Albert ♦

Édith Le Merdy

as Simone Margantin

Josette Ménard

as Mamy ♦

Emy Lévy

as Brothel girl 1 ♦

Laura Stainkrycher

as Brothel girl 2 ♦

Lucie Brezovská

as Brothel girl 3 ♦

Vera Havelková

as Brothel girl 4 ♦

Jan Kuzelka

as Brothel customer ♦

Dominique Paturel

as Lucien Roupp ♦

Nicholas Pritchard

as Jameson ♦

William Armstrong

as Clifford Fisher ♦

Martin Sochor

as O’Dett audience member ♦

Frédérique Smetana

as O’Dett audience member ♦

Lenka Kourilova

as O’Dett audience member ♦

Pierre Derenne

as P’tit Louis ♦

Jan Filipensky

as Fire eater ♦

Laura Menini

as Circus dancer ♦

Oldrich Hurych

as Clown ♦

Mathias Honoré

as M. Loyal ♦

Diana Stewart

as American woman ♦

Jean-Jacques Desplanque

as Tony Zale ♦

Alain Figlarz

as Boxing trainer ♦

Robert Paturel

as Boxing ring corner-man ♦

Alban Casterman

as Charles Aznavour ♦

Olivier Cruveiller

as Inspecteur Guillaume ♦

Sébastien Tavel

as Interviewer ♦

Agathe Bodin

as Suzanne ♦

Nicole Dubois

as Seamstress ♦

Martin Janis

as Jean Mermoz ♦

Eric Franquelin

as Etienne ♦

Marc Chapiteau

as Mitty Goldin ♦

Maureen Demidof

as Marcelle ♦

Philippe Bricard

as Man in Lannes ♦

Olivier Raoux

as Waiter ♦

Nathalie Cox

as Pin-up ♦

Pierre Peyrichout

as Journalist ♦

Helena Gabrielová

as Drunk woman ♦

Jaroslav Vízner

as New year’s eve man ♦

Sophie Knittl

as Bar customer ♦

Hélène Genet

as Bar customer ♦

Farida Amrouche

as Aïcha ♦

Liliane Cebrian

as Palm reader ♦

Nicolas Simon

as Journalist by the church ♦

Pascal Mottier

as Boy ♦

Thierry Guibault

as Ostende doctor ♦

Garrick Hagon

as American doctor ♦

Ginou Richer

as Neighbor ♦

Vladimír Javorský

as Street spectator ♦

Denis Ménochet

as Journalist in Orly ♦

David Jahn

as A soldier ♦

Sylvie Guichenuy

as A woman in the street ♦

Fabien Duval

as Policeman ♦

Maya Barsony

as Girl at the bar counter ♦

Paulina Nemcova

as American journalist ♦

Rodolphe Saulnier

as Barman ♦

Fedele Papalia

as Diner waiter ♦

Zdena Herfortová

as Woman Etoile Cafe ♦

Pier Luigi Colombetti

as Brasserie owner ♦

Olivier Carbone

as Transvestite ♦

Laurence Gormezano

as Brasserie waitress ♦

Christophe Kourotchkine

as Civilian policeman ♦

Christophe Odent

as Dr. Bernay ♦

Robert Nebrenský

as Docteur in Dreux ♦

Jaromír Janecek

as Show manager in Dreux ♦

Christopher Gunning

as Orchestra conductor ♦

Richard Hein

as Orchestra conductor ♦

Elliot Dahan

as Child ♦

Isaac Dahan

as Child ♦

Jil Aigrot

as Edith Piaf (singing voice)

Directed by: Olivier Dahan

Written by: Isabelle Sobelman

Written by: Olivier Dahan

Co-producer: Timothy Burrill

Assistant producer: Axel Decis

Producer: Alain Goldman

Co-producer: Marc Jenny

Co-producer: Oldrich Mach

Associate producer: Catherine Morisse

Line producer: Marc Vadé

Music: Christopher Gunning

Cinematography: Tetsuo Nagata

Editing: Richard Marizy

Casting: Olivier Carbone

Production design: Olivier Raoux

Art direction: Beata Brendtnerovà, Mick Lanaro, Laure Lepelley, Stanislas Reydellet

Set decoration: Stéphane Cressend, Petra Kobedova, Cecile Vatelot

Costumes: Marit Allen

Makeup and hair: Jan Archibald, Linda Dvorakova, Barbara Kichiova, Ruzena Novotna, Loulia Sheppard, Ivo Strangmüller, Catherine Jabes, Stephanie Hovette, Jemma Scott-Knox-Gore, Richard Glass, Chris Lyons, Nathaniel De’Lineadeus, Didier Lavergne, Amélie Bouilly, Elisa Costa, Gabriela Polakova, David White, Matthew Smith

Post-production manager: Abraham Goldblat

Production manager: Michal Prikryl