‘Last Tango in Paris’ — Paul talks to his dead wife, but it’s

his co-star who speaks from beyond the grave

“Last Tango in Paris” is not Brando playing Paul, but Paul playing Brando.

This is sort of what Roger Ebert is driving at in his third and last review of “Tango,” written in 2004 for his “Great Movie” series. Paul talks to his wife’s corpse. Ebert suggests it’s possible Brando “was talking to his own dead body.”

Or perhaps he was just warming up for Col. Kurtz. Paul is every bit Marlon 1972, overrun by eccentricities, in physical decline, maddeningly charming, outrageously boorish, fading handsome, part of the system, mocking the system. Those of a younger age who became acquainted with Marlon Brando’s work around the time of “The Godfather” or later know him as someone who would either A) do whatever the hell he wanted or B) do sort of what you wanted him to do as long as you obscenely overpaid him. Paul is 100% capable of sending “Sacheen Littlefeather” to the Academy Awards podium.

In his original 1972 assessment, Ebert in his lead sentence decided “Tango” amounts to “one of the great emotional experiences of our time.” He says the film is “about need” and is “a cry for help,” but the more reasoned analysis suggests it’s little more than a middle-age man having his way, on demand, with a spectacularly gorgeous, nude 19-year-old with no strings attached. (Who ... in the world ... would ever fantasize about that sort of arrangement.) Viewers get either a depiction of sex or a topless/fully nude bombshell seven times in the film. An emotional powerhouse would only be occurring here if Paul did not copulate with Jeanne.

Paul’s wife has passed away. Director/auteur Bernardo Bertolucci will only slowly deliver the impact of this event. And so, curiously, what Paul has got going from the beginning of “Tango” is, for many males, too good to be true. He’s free to have sex with a woman decades younger, a complete stranger, hours later. (But he convinced even the toughest critics that this isn’t hedonism; it’s really a cry for help.) Bertolucci seems oblivious to the hint, the serious possibility, of parody; one almost wonders if anyone pulled him aside and asked, “You actually believe this?” Well, on some levels, we should, which is why “Tango” is a significant and enduring work.

The film is, remarkably, years ahead of its time — the recitations of Paul are similar to what we will hear from Col. Kurtz in “Apocalypse Now.” Both characters are driven by extreme stress and will encounter a stranger, subdue the stranger, exploit the stranger, then let their guard down and yield to the stranger. How Bertolucci and Francis Coppola each reached these conclusions in wholly separate projects is a great incentive for one of those Hollywood forums. That’s conceding Kurtz didn’t bother to stick his gum someplace before Willard’s attack.

“Last Tango” is quite possibly the most controversial film ever made. That might be the case had it only stopped with the pornography complaints in 1972. Then, it smashed the very thin line between those who believe movies can or should be a high art form and those who believe they are mainstream entertainment. (Despite what Robert Altman’s “The Player” implies, history has shown they are both, an unsatisfying partnership for many.) But that wasn’t all. “Tango” managed to cause an uproar four decades later when its female lead, Maria Schneider, was quoted (or misquoted, depending on what you believe) as suggesting a rape occurred in the filming.

Pauline Kael, whose 1972 review was dubbed by Roger Ebert “the most famous movie review ever published,” was hooked, gushing that “The movie breakthrough has finally come” and that “Tango” would parabolically (that is not her term) expand moviemaking boundaries into an elevated arthouse genre in which stark sexuality and emotions would not be scowled at but routinely accepted as important contributions to humankind’s search for truths. That battle probably began in earnest years earlier. There was “Bonnie and Clyde.” There were “Midnight Cowboy” and “A Clockwork Orange.” The latter, initially rated X, were revised to R within barely a year. Against this momentum, “Last Tango” delivered the last verdict. It lost. Ebert concluded that “Tango” was “not a breakthrough but more of an elegy” for the kind of movies Kael wanted, “all but crushed” by Hollywood’s determination to round down the shock factor in pursuit of mass entertainment.

The mere thought of “Tango” was electrifying. Kael’s October 1972 review was published a couple weeks after she saw it at the closing night of the 1972 New York Film Festival. Imagine being among the attendees of this showing. It was the film’s debut. It next went to Italy before returning to America in 1973. It was a time when no one had streaming services and virtually no one had VCRs/cable TV and there was a sensation in going to a theater to be part of an exclusive audience, particularly to see not just a sexy, nude, unknown European woman but Marlon Brando, who had just months earlier stormed back to Hollywood’s mountaintop with his portrayal of Vito Corleone. He’s on fire. What’s he going to do next. A very select few will find out.

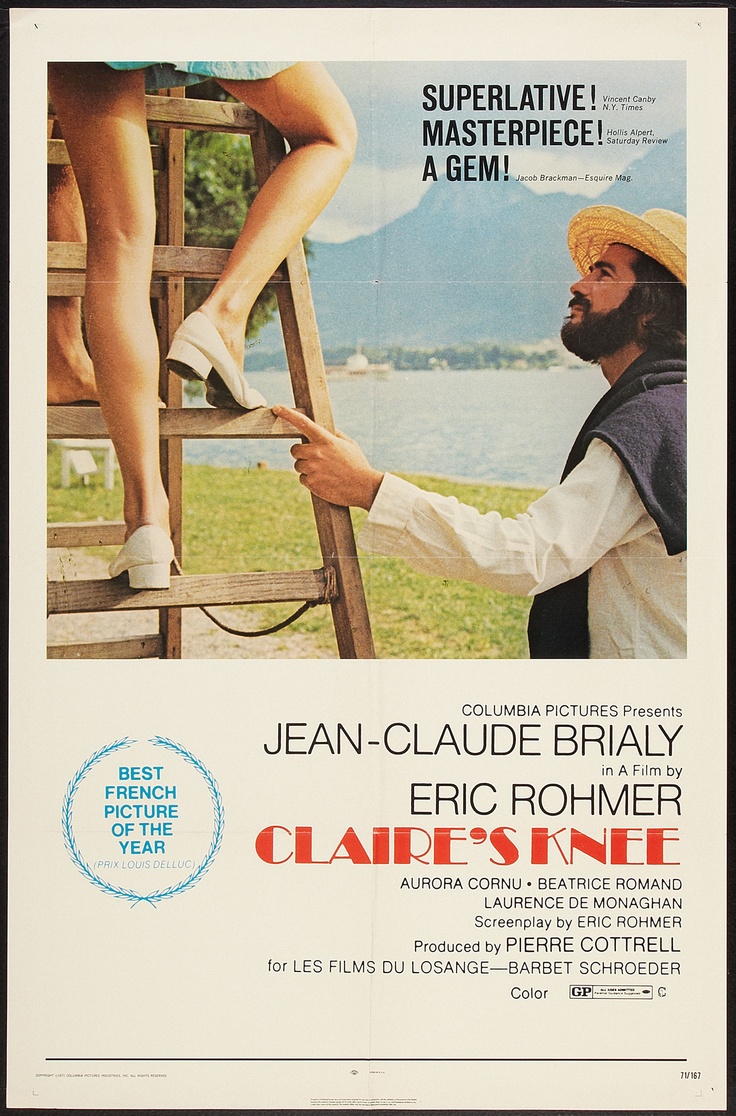

But while Kael seemed to find the film extraordinarily unique, it has much in common with three other acclaimed films of roughly the same time, all based in France, two of them also featuring Jean-Pierre Léaud. There was Éric Rohmer’s “Claire’s Knee,” there was Francois Truffaut’s “Day for Night,” and there was Jean Eustache’s upstart “The Mother and the Whore.” All, like “Tango,” suggest semi-random, spontaneous sex is the greatest kind. All four movies make excuses for what amounts to sleeping around as often as possible. The curiosity is in what those excuses are. “Claire’s Knee” suggests the invitations and green light are so compelling, who can resist, but if a man can restrain himself, he’ll actually be better off. “Day for Night,” in which Dani might even be less interested in Léaud’s character than Schneider is in “Tango,” tells us that our livelihoods go a long way toward choosing our sex partners and any grievances committed under that umbrella must be forgivable. “The Mother and the Whore” suggests a genetic compulsion of women to serve men who don’t come close to deserving them and that the men would offend them by refusing.

In “Tango,” the excuse is grief. His pain is so great, he must have sex. These people have nothing in common. They’ve no reason to be together. But he’s hurting. And she’s bored. Suddenly, he’s got an idea. So she acquiesces. In their first tryst, Jeanne is (extending this cinematic comparison) the mother, but quickly she will serve Eustache’s role of the whore, Paul’s on-demand outlet for ... coming to grips with the suicide of his wife.

“You and I are gonna meet here without knowing anything that goes on outside here,” Paul commands Jeanne.

The production is more than sex. But “Tango” nowadays is most famous for what emerged only recently as one of the strangest Hollywood controversies. Strange because of its gestation period.

In 2007, three years after the death of Brando, a Daily Mail interview with Schneider marking the 35th anniversary of the film was headlined (without quotes), “I felt raped by Brando.” The actual quote refers to one scene, the butter scene, which Schneider complains was not in the script and thus something she could’ve, and would’ve, refused had she only known better. “I felt humiliated and to be honest, I felt a little raped, both by Marlon and by Bertolucci,” is what she said.

That story barely made a ripple, and six years later, Bertolucci in a German interview insisted the scene, but not the butter, was in the script. He said Schneider wasn’t told about the butter because he “wanted Maria to feel, not to act, the rage and the humiliation.” (Did that tactic work? Roger Ebert decided “she is not crying about the sex and indeed doesn’t seem to be thinking about it.”)

Still, the subject received little notoriety. It wasn’t until late 2016 when a Spanish nonprofit, of all entities, raised Bertolucci’s comments in a campaign protesting violence against women. That set off an outcry.

There was this ambiguous Twitter comment from the actress Jessica Chastain: “To all the people that love this film- you’re watching a 19yr old get raped by a 48yr old man. The director planned her attack. I feel sick.”

Is Chastain saying Schneider was raped during the filming? Schneider said “I felt a little raped, both by Marlon and by Bertolucci,” but she also said in that interview, “What Marlon was doing wasn’t real.”

Bertolucci’s acclaimed photographer, Vittorio Storaro, assessed the “rape” claim this way to the Hollywood Reporter: “It’s something that some ignorant journalist put together. I was really disgusted by what was written, which is not true at all. I think the journalists are making an issue that is not really an issue. I read that there was a kind of violence made on her but that’s not true. That’s not true at all. That’s terrible. I was there. We were doing a movie. You don’t do it for real. I was there with two cameras and nothing happened. ... Nobody was raping anybody. That was something made up by a journalist.”

Perhaps Chastain is asserting that the scene is a depiction of a rape and that such a depiction should be taboo. Chastain inadvertently touched upon an important subject — that if even the most elite critics don’t agree on whether an elite filmmaker has depicted a rape ... or if elite critics are blown away by the same character even though one believes the character committed rape and others believe the character is simply having sex ... then maybe there’s a big problem here in #MeToo perceptions.

Roger Ebert’s 1972 review stated, “Paul rapes her, if rape is not too strong a word to describe an act so casually accepted by the girl.”

But that only adds to the confusion. Ebert was referring to the first encounter between Jeanne and Paul, which involved no butter.

Pauline Kael’s review did not suggest the term “rape.” Here’s how she saw it: “They have sex in an empty room ... she is so erotically sensitized by the rounds of lovemaking ... She lends herself to an orgiastic madness, shares it, and then tries to shake it off.”

Vincent Canby called it “The movie romance of the 1970s.”

By 2016, the New York Times proved indecisive on whether a rape occurred, onscreen or off. This 2016 Times account of the controversy refers to the “infamous rape scene” and assures that Schneider’s “felt a little raped” comments at the time “did not go unnoticed — they figured prominently in her obituary in The New York Times.” But that obituary, aside from Schneider’s quote, does not use the term or state that either Schneider or her character were raped. It describes the scenes as a “torrid affair” and “erotically charged relationship.”

“Tango” is beautifully shot. The score is often mesmerizing. The opening notes are irresistible, delivered while credits roll alongside art by Francis Bacon (the Irish artist, not the English philosopher). The title font, seen on posters and advertising, is appealing. The title is beautiful, actually implying much more than what’s there.

Bertolucci received a best-director Oscar nomination for “Tango,” losing to George Roy Hill (“The Sting”). “Tango” did not receive a best-picture nomination nor best-foreign-language-film nomination. Whether it qualified for the latter, and what year it would've qualified, is difficult to determine; it is a rare transcontinental film with occasional dialogue in English, which works against films in the foreign-language category. Bertolucci is said to have devised the film based on his own fantasies. He knows precisely what he wants from Schneider and gets it, spectacularly. He knows she appears younger than her 19/20 years. She first is seen wearing a hat, quite possibly the most beautiful any actress has ever looked wearing a hat. Later she will be topless while wearing jeans, almost certainly the movies’ sexiest jeans-without-top look.

Bertolucci and Brando surely thrived on the controversy and censorship of “Tango.” Schneider, who turned 20 during filming, surely did not. At that age, she is legally able to make decisions about the exposure of her body, but the consequences of these particular decisions were certainly much greater than a 19-year-old can be expected to realize, a conundrum for an ambitious filmmaker.

Schneider is far more model than actress in this film. That is no complaint; her appearance is spectacular, powerful, lightning in a pop culture bottle, something only a small number of actresses get a chance to achieve. “Tango” and “10” have much in common. A female can achieve extraordinary, permanent cinematic fame in such a role, but it can’t sustain a career, because once the mass audience has seen her, the thrill subsides. Ebert in his original “Tango” review writes 1,070 words before mentioning Schneider’s name. He wrote then that she “doesn’t seem to act her role so much as to exude it,” and, “it’s impossible to really say whether she can act or not.” In his 2004 update, it takes 768 words to mention Schneider, but he decided his previous dismissal of her role was a misjudgment, writing she “shares the film with Brando and meets him in the middle.”

Schneider, who died of breast cancer at 58 in 2011, said in her 2007 Daily Mail interview that her agency forced her to do the film. “I was too young to know better. Marlon later said that he felt manipulated, and he was Marlon Brando, so you can imagine how I felt. ... I felt very sad because I was treated like a sex symbol — I wanted to be recognized as an actress and the whole scandal and aftermath of the film turned me a little crazy and I had a breakdown.”

She continued: “I was so young and relatively inexperienced and I didn’t understand all of the film’s sexual content. I had a bit of a bad feeling about it all. To be suddenly famous all over the world was frightening. I didn’t have bodyguards like they do today. People thought I was just like my character (presumably there should be a comma here) and I would make up stories for the press, but that wasn’t me.” All of that, she said, “made me go mad.”

There is certainly off-screen tragedy here. Schneider battled drug problems, rejected offers, fought with filmmakers and faded from legend. The Daily Mail writer nevertheless described her as “extremely chatty and giggly.” She came out in the 1970s as bisexual, had no children and was survived by longtime partner Pia Almadio.

But in a 1975 interview with Roger Ebert, Schneider’s complaint about Bertolucci is that he “made me wear very heavy black makeup under my eyes. Makeup on a girl who’s too young gives her the wrong character, gives her a funny look. I argued with him, but with no luck.” Also, she said Bertolucci failed to look after crew members, but Brando did. “Marlon was such a good force on the picture ... He was wonderful to work with ... he gave me the advantage, the material to work with. And he was brilliant when we improvised,” Schneider said.

One person who handled movie mega-success extremely well at a young age was Jean-Pierre Léaud, now 74. A prodigy of both Truffaut and Godard, his CV of landmark roles is enormous. “Tango” is not one of them. The movie sucks, frankly, whenever he appears. There’s a long list of movie couples who are unbelievable, but this pairing of Schneider’s Jeanne with Léaud’s Tom is near the top. Perhaps the film’s most dubious scene has nothing to do with butter but everything to do with floating, in the form of the life preserver labeled “L’Atalante.” Bertolucci’s implication is that Schneider is beautiful enough to land a handsome, spirited man ... who does absolutely nothing for her (and apparently vice versa). Even so, Bertolucci’s dubious idea of having Tom’s film crew intrude on their engagement puts Bertolucci way out in the vanguard — by about 30 years — of the reality TV phenomenon.

Somehow — and this is hardly unique in cinema — Jeanne has no friends. Surely there must be bridesmaids for her wedding. Surely she would be interested in telling someone that her fiance is filming their engagement but that he is missing her trysts with a decrepit man more than twice her age. No, not here, that is artistic license.

Nobody’s getting any STDs here. Nobody actually wants to go shopping or go see a movie or watch television. (In fairness, they weren’t really interested in those things in “The Mother and the Whore” either.)

“Tango” includes two mothers who collectively supply only one useful soundbite, when Rosa’s mother’s hand is bitten, and she further begins to realize why her daughter may have made a fateful decision.

Bertolucci’s Paris, an oft-filmed city, is not bleak but spontaneous. Open the door of despair, you might bump into glory. Low-budget prostitution interacts seamlessly with high-end aspirations. There is a richness to the bare-bones apartment; it feels as if the characters are allowed to paint their own Parisienne canvas. Bertolucci cleverly uses mirrors, but so have many great directors. He clearly was fascinated with frosted glass. It is an intriguing motif for its ambiguity — it’s not a clear view of the characters, but it’s not privacy either. Somewhere in between.

The most famous American to go to Paris to decline and die was Jim Morrison. That occurred in 1971. There’s a movie about that too. Could “Last Tango” have been inspired by this event? That seems doubtful on the part of Bertolucci given that Morrison died only months before filming began, but it’s within the realm of possibility for Brando.

Ebert’s reviews of this film aren’t among his best, but he makes the most convincing point — this might be Brando playing himself. Ebert suggests that the scene in which Paul speaks to his dead wife is Brando assessing his own career. But the whole movie is what movie buffs, and eventually Jeanne, know about Brando. Temperamental, mercurial, enormously charming when he wants to be; enormously off-putting when he doesn’t. Disdainful of the mainstream. One beautiful scene is his conversation with his wife’s lover in which he seems to find a bond with the man only to scoff on the way out the door, what did she ever see in him.

You can’t trust Paul. But can you trust the ending? Ebert says “I don’t know” but allows that at a minimum, it supplies something that needs to be supplied. Ebert posits that Paul “was willing to let life have one more chance with him,” apparently in the form of a permanent partner who is capable of empty-apartment trysts while engaged. Paul should let Jeanne walk and look up the people in “The Mother and the Whore” and see if they’ve got room for a fourth.

“Last Tango in Paris” was famously overrated by Kael, but her enthusiasm is catchy. “The whole film is alive with a sense of discovery,” she wrote, and there is something electric in watching Brando’s last acclaimed performance. He would still be paid enormous amounts to play Jor-El and Col. Kurtz, but unbridled with the foreign freedom of Bertolucci, “Tango” is Brando’s final tour de force, the last stand of the film world’s Bobby Fischer (that’s a bit of a stretch, but only a bit), making what was surely his last move of pure artistic motivation.

White hot because of “The Godfather” (and perhaps because of Sacheen Littlefeather), Brando would receive a best-actor nomination a year later for his performance as Paul. He and Jack Nicholson and Al Pacino and Robert Redford all lost to Jack Lemmon (“Save the Tiger”) in what has to be one of Oscar’s most startling upsets. Acknowledging recent shunning of the best actor Oscar at recent ceremonies, Lemmon declared at the podium, “It is one hell of an honor, and I am thrilled.” Paul couldn’t have cared less.

3 stars

(August 2018)

“Last Tango in Paris” (1972)

Starring

Marlon Brando as Paul ♦

Maria Schneider as Jeanne ♦

Maria Michi as Rosa’s Mother ♦

Giovanna Galletti as Prostitute ♦

Gitt Magrini as Jeanne’s Mother ♦

Catherine Allegret as Catherine ♦

Luce Marquand as Olympia ♦

Marie-Helene Breillat as Monique ♦

Catherine Breillat as Mouchette ♦

Dan Diament as TV Sound Engineer ♦

Catherine Sola as TV Script Girl ♦

Mauro Marchetti as TV Cameraman ♦

Jean-Pierre Leaud as Tom — un cinéaste, le fiancé de Jeanne ♦

Massimo Girotti as Marcel ♦

Peter Schommer as TV Assistant Cameraman ♦

Veronica Lazar as Rosa ♦

Rachel Kesterber as Christine ♦

Ramón Mendizábal as Tango Orchestra Leader ♦

Mimi Pinson as President of Tango Jury ♦

Darling Légitimus as La concierge ♦

Gérard Lepennec as Un déménageur ♦

Stéphan Koziak as Un déménageur ♦

Armand Abplanalp as Prostitute’s Client

Directed by: Bernardo Bertolucci

Written by: Bernardo Bertolucci (story and screenplay)

Written by: Franco Arcalli (screenplay)

Written by: Agnes Varda (adaptation French dialogue)

Producer: Alberto Grimaldi

Music: Gato Barbieri

Saxophone solo: Gato Barbieri

Music, arranged and conducted: Oliver Nelson

Cinematography: Vittorio Storaro

Editing: Franco Arcalli, in collaboration with Roberto Perpignani

Costumes: Gitt Magrini

Production design: Philippe Turlure

Set decoration: Philippe Turlure

Production manager, France: Gerard Crosnier

Production manager: Mario Di Biase

Makeup and hair: Maud Begon, Iole Cecchini

Still photographer: Angelo Novi

Thanks: Francis Bacon