A ‘Notorious’ woman spies

her way into Cary Grant’s heart

After Claude Rains closes the door, you have to wonder what he might say to get himself out of this pickle.

Given decades to think about it, one could offer this advice: Tell them that Devlin has stolen your wife. Tell them she married you for the money, you quickly found this out, confronted her, and she admitted she was really in love with Devlin, who invented a ruse to steal her away.

Whatever you do, don’t tell them what they found in the wine cellar.

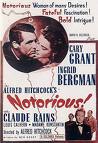

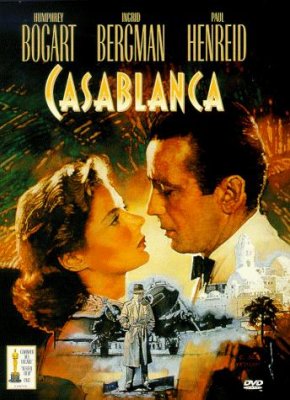

“Notorious” is a spectacular combination of three Hollywood giants in their prime. As films of the greats go, it is underrated. Ingrid Bergman has “Casablanca,” Cary Grant has “North by Northwest” and Alfred Hitchcock has “Psycho,” “Rear Window,” “Vertigo,” etc. This one is arguably better than all of the above. It is not a gushing romance; its signature scenes involving kissing and staircases represent unbridled suspense but restrained passion.

What it does have is a decided element of cynicism, and a tantalizing romance that is so close but just out of reach, to the point you’re anxious for it after the film is over.

The central question in “Notorious” is whether Devlin is using the spy operation to court Alicia — or whether Devlin is romancing Alicia merely to advance the operation. Optimists will hope it’s the former. Does Devlin himself even know? We see his reactions during moments when Alicia is disparaged. He seems like a torn lover blowing his cover, but he might also be a skilled operator defending his contact.

Only near the end, when he volunteers to visit her home in a gesture unnecessary for the mission, is there a convincing — though not entirely conclusive — vote as to his sentiments.

Hitchcock is notorious himself for a healthy suspicion of authorities. This film is not so far removed from “North by Northwest.” Both depict the government using a beautiful woman to get into the inner circle of some very dangerous men. It’s Cary Grant’s job to help her do so while protecting her at the same time. The difference is that in “Notorious,” Grant’s character is a willing participant. And in one film he is the pro; the other, an amateur.

“Notorious” also features a villain that is more effective than the one depicted by James Mason in “Northwest.” The bad guys here are the Nazis, which to this day are a compelling enemy. The film was set and produced in 1946, a time when the presumed goal of existing Nazis would be survival, not counter-attack. But nevertheless there is great intrigue in purported South American Nazi activity, a film theme that was just beginning with “Notorious” and will doubtlessly continue this century.

Is the assessment of the enemy by Devlin’s group accurate? If escaped Nazis are truly on the verge of manufacturing nuclear weapons in Rio, one might question where and how they would deploy them. They don’t seem to be into terrorism (for the most part, a much later concept). Would they overthrow the Brazilian government and run a police state of German exiles? Or would they merely smuggle the weapons back to Deutschland to drive out the occupying forces?

The U.S. approach adds to the skepticism of the plot. If agents know that the Germans are mining uranium, they would presumably rout and arrest the whole group. Captain Prescott explains why they don’t. “It would do no good. Even if we arrest their leader, Alexander Sebastian, tomorrow another foreign man takes his place and the work goes on.” Nobody challenges this strangely weak answer, probably because it has forever been a movie given that technicalities must preclude authorities from busting obvious crime plots so that the characters can be put in the most dangerous situation possible (“Traffic” and “The Departed&rdquo being recent examples). The dubiousness of this claim might in other films erode credibility, but in “Notorious” only adds to the idea that the authorities might be overdoing or overthinking things.

“Notorious” would be an effective film with any pair of stars. It is blessed to have perhaps the two greatest. And clothing them is Edith Head. Hitchcock knows that one thing the viewer does not want to see is Bergman in rags. The plot nicely accommodates numerous scenes in formal attire, as though she were attending the Oscars. Grant is given a matching look to keep up with her. His riding jacket is probably the greatest sport coat depicted in film, and his complete wardrobe rivals Jack Nicholson’s in “Chinatown.”

Bergman hits the basic trifecta — very brave, very beautiful, very vulnerable — while Grant easily handles the role of resistor. Their look is an overwhelming part of who they are, but by 1946, Grant and Bergman were highly skilled, extremely seasoned actors. Here, they are masters of the nuance. Bergman’s best scene is when she reports the marriage proposal to the U.S. agents. She is noticeably proud of her spying achievement but also is trying to push Devlin’s buttons. If Devlin says no, that means he truly loves her and that is what she hopes to hear. If he agrees, then he does not love her, but at least she has scored a spying coup.

Devlin’s deadpan response: “I think it’s a useful idea.”

“He’s in love with me,” Alicia tells them, referring to Sebastian of course but wishing it was Devlin. “He thinks you’re in love with him?” she is asked, and she replies, “Yes.”

“Then it’s all right,” Captain Prescott cheerily declares, but Devlin is not done digging under Alicia’s skin, asking, “Mr. Sebastian is a very romantic fellow, isn’t he Alicia?” Grant’s tone has changed, from the sarcastic “useful idea” quip to a comment that is half ultimate condemnation, half desperate lament of a man struggling to decide if he has been giving her the wrong answer all along.

Viewers do not quite know enough about Alicia’s past to render judgment. This is suspenseful filmmaking, as it forces them to rely on Devlin’s evolving assessment of her. What, exactly, is her ethnicity? Huberman is a Jewish name but not necessarily exclusively Jewish. Her father is a German convicted of treason against America. Does it all fit together? No. From enough characters’ comments, we know she has a reputation. But is it well-deserved? She does not much deny it. In the early party scene, she is drunk, and she flirts with the silhouette eventually revealed to be Devlin. She asks him if he wants a drink. “How about you, handsome,” and, “You know something, I like you.” She sports a bare midriff that even Devlin isn’t comfortable with.

Maybe she falls for him too easily and only accepts the spy job for that reason. But maybe not. Despite her drunken comments, she does not immediately warm to Devlin — even after he is revealed to be a federal agent — as one might expect of a woman of ill repute. It takes a wiretapped recording of her sentiments to persuade her to take the job. “Why should I?” she asks. “Patriotism,” Devlin replies, and we know that is one of her qualities.

The extent of her romance with Sebastian is also unclear. After dating him, she meets Devlin at a racetrack to deliver a report. They know Sebastian might be watching, so their conversation and expressions are partly phony. They smile while pretending to watch the horses. Alicia eventually tells Devlin, “You can add Sebastian’s name to my list of playmates,” and Devlin suddenly grimaces. She seems to be telling the truth; if not, why would she volunteer that information? Well, maybe to make Devlin jealous, and to view his reaction, which is difficult because of the play-acting they are carrying out.

After the marriage, Alicia and Sebastian sleep in separate beds. There is no hint of intimacy between them. Has Alicia really ever consummated their relationship, or has she merely agreed to be a trophy to advance the spy case and make Devlin jealous?

Alicia proves to be a natural at the art of spying but capable of a rookie mistake. She seems too inquisitive about locked closets and champagne stockpiles, and she reveals herself by replacing the Unica key. But when caught in a jam, she can act her way out of it. Devlin of course is a pro at this. His reaction to Sebastian spotting them outside the wine cellar is one of the great unexpected moments of cinema. And the way Alicia goes along with it after a quick panic reinforces her ability to react to a problem. There are not many scenes in thrillers that can top this one, but “Notorious” actually can, in the final descent down Sebastian’s staircase.

Cary Grant had established a man-of-the-world persona by the time of this film, but rarely was he this icy. Devlin is not the troubling character of “Suspicion,” but he is far removed from the Roger Thornhill or Tom Winters of Grant’s later films. He is a cool, methodical operator, even in his love life. One gets the feeling very few women excite him. Alicia’s ability to produce the slightest betrayal of his expressions is a victory on her part.

“Notorious” excels at a classic concept mostly extinct from Hollywood today. That is the idea of gentlemanly conflict. Guns are not needed in “Notorious,” and punches need not be thrown. Devlin insults the wife of a fellow agent who disparaged Alicia, and Devlin’s subsequent comment is, “Withdrawn, apologized sir.” Devlin might be trying to steal Sebastian’s wife, but Sebastian nevertheless plays by the rules and is courteous to Devlin. Today’s cinema prefers something along the lines of “The Wedding Crashers,” where angry characters play a rough game of football and threaten to do much worse. “Notorious” is a gloriously civil conflict with a parallel to “Wall Street,” another film reviewed on this site.

Claude Rains, as Sebastian, fits the mold of so many Hitchcockian males. They tend to have issues with overbearing mothers, in this case Madame Sebastian, played by Madame Konstantin who, in an arrangement similar to the Angela Lansbury-Laurence Harvey team in “The Manchurian Candidate,” was actually born only three years before Rains. The mothers always know, and Alex is foolish to disregard her initial suspicions, even if he is correct about her meddling. Rains is an appealing villain — perhaps a bit too likable as a Nazi sympathizer in this film and “Casablanca.” He has too much heart and not enough brains. Neither he nor his mother concludes that if Alicia is an American agent, the man she is regularly bumping into might be also.

The Hitchcock trademark is also evident in other ways; there are checkered floors, automobile adventures and a couple of very crucial scenes taking place on staircases. One could say this movie is at heart a Cary Grant work, or an Ingrid Bergman work, or an Alfred Hitchcock work, and all three answers would be correct.

Rarely does a romance feel so exhilarating, and so incomplete, at the same time. Devlin has done to the audience what he has done to Alicia, leaving them wanting so much more. Going out on this high note makes “Notorious” one of the greatest motion pictures.

4 stars

(November 2008)

“Notorious” (1946)

Starring Cary Grant as T.R. Devlin ♦ Ingrid Bergman as Alicia Huberman ♦ Claude Rains as Alexander Sebastian ♦ Louis Calhern as Captain Paul Prescott ♦ Madame Konstantin as Madame Anna Sebastian ♦ Reinhold Schunzel as Dr. Anderson ♦ Moroni Olsen as Walter Beardsley ♦ Ivan Triesault as Eric Mathis ♦ Alex Minotis as Joseph - Sebastian’s Butler ♦ Wally Brown as Mr. Hopkins ♦ Sir Charles Mendl as Commodore ♦ Ricardo Costa as Dr. Julio Barbosa ♦ Eberhard Krumschmidt as Emil Hupka ♦ Fay Baker as Ethel ♦ Bernice Barrett as File Clerk ♦ Bea Benaderet as File Clerk ♦ Candido Bonsato as Waiter ♦ Charles D. Brown as Judge ♦ Eddie Bruce as Reporter ♦ Paul Bryar as Photographer ♦ Aileen Carlyle as Woman at Party ♦ Beulah Christian as Woman ♦ Richard Clarke as Man ♦ Tom Coleman as Court Stenographer ♦ Alfredo DeSa as Ribero ♦ Ben Erway as Reporter ♦ Bess Flowers as Party Guest ♦ Almeda Fowler as Woman ♦ Gavin Gordon as Ernest Weylin ♦ William Gordon as Adams ♦ Virginia Gregg as File Clerk ♦ Harry Hayden as Defense Counsel ♦ Alfred Hitchcock as Man Drinking Champagne at Party ♦ Warren Jackson as District Attorney ♦ Ted Kelly as Waiter ♦ Donald Kerr as Reporter ♦ James Logan as Reporter ♦ Leota Lorraine as Woman ♦ George Lynn as Photographer ♦ Frank Marlowe as Photographer ♦ Frank McClure as Man Walking Through Door Leaving Courtroom ♦ Francis McDonald as Man ♦ Tina Menard as Maid ♦ Howard M. Mitchell as Bailiff ♦ Bert Moorhouse as Diner Extra / Party Guest ♦ Antonio Moreno as Senor Ortiza ♦ Sandra Morgan as Woman ♦ Howard Negley as Photographer ♦ Ramon Nomar as Dr. Silva - Brazilian Official ♦ Fred Nurney as John Huberman ♦ Garry Owen as Motorcycle Policeman ♦ Jeffrey Sayre as Party Guest ♦ Louis Serrano as Brazilian Official ♦ Patricia Smart as Mrs. Jackson ♦ Dink Trout as Court Clerk ♦ Lenore Ulric as Horsewoman with Sebastian ♦ Emmett Vogan as Reporter ♦ Friedrich von Ledebur as Knerr ♦ Peter von Zerneck as Wilhelm Rossner ♦ John Vosper as Reporter ♦ Alan Ward as Reporter ♦ Lillian West as Woman ♦ Frank Wilcox as FBI Agent ♦ Herbert Wyndham as Mr. Cook

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock

Written by: Ben Hecht

Written by: John Taintor Foote (story)

Written by: Alfred Hitchcock (contributor)

Written by: Clifford Odets (contributor)

Producer: Alfred Hitchcock

Original music: Roy Webb

Cinematography: Ted Tetzlaff

Editing: Theron Warth

Art direction: Carroll Clark, Albert S. D’Agostino

Set decoration: Claude Carpenter, Darrell Silvera

Makeup: Mel Berns

Costumes and wardrobe: Edith Head