Cillian Murphy nails

‘Oppenheimer’ dead-center

Is the weapon that is the source of so much activity in “Oppenheimer” an offensive, or defensive, one? How that question is being answered steers the film from its invigorating scientific achievement to its descent into messy Washington politics. That conclusion, with too many names involved in the backstabbing to keep track of, would be nearly unwatchable except that it includes a historic guilt trip that may or may not be a whim of artistic license.

“Oppenheimer” is the triumph of centrist leadership. He could get along with people. He listened to them. All kinds of different people, some of them difficult or eccentric. That’s why he was chosen. That’s why he succeeded.

If you find one of the film’s earliest scenes, involving an apple, at odds with that conclusion, you are correct. Is it true, and why is it shown.

What is shown is certainly not completely true, the idea of such a promising young man making such a lethal decision, then racing back on second thought just in time to prevent an unintentional tragedy. It was not an invention of director Christopher Nolan but an anecdote in the movie’s source, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer’s grandson, Charles Oppenheimer, who approves of the rest of the film, told The Hollywood Reporter he “definitely” would have cut that scene, stating the book authors admit they don’t know if it happened, and “There’s not a single enemy or friend of Robert Oppenheimer who heard that during his life and considered it to be true.” Apparently the story surfaced from a friend of Oppenheimer’s who said the scientist once revealed it to him and, unlike the portrayal in the film, was nearly expelled over it.

These are the types of anecdotes filmmakers love. It’s entree to artistic license. Nolan presumably includes the scene because it is, remarkably, the film’s greatest drama. Otherwise this is a figure whose life and work are well known; we know what he’s going to do and how it ends. Shortly after this episode, there is a soundbite about analysis. Does this supposed incident explain his future motivation or behavior in any way? That this person, scarred by a youthful impulse and perhaps a little unhinged, realized he doesn’t like playing executioner, however powerful it may make him feel? That seems too big of a leap and not an area where Nolan really wants to go.

Discussing his film in July 2023, Nolan in a New York Times interview could not explain “Why now?” His answer is that “it’s always seemed one of those stories that I don’t think it’s been told in any definitive movie sense.”

Nolan’s right about that, which makes his timing curious. Robert Oppenheimer was not the subject of prominent feature films in the 1960s or ’70s or early ’80s, when we had the Cuban Missile Crisis and “The Day After.” Nolan’s film is a work that by its existence is passing judgment on controversial policy 80 years after it occurred, when protests have long faded (when was the last no-nukes rally you saw in the news?), when the principals have long since passed and can’t take issue with the portrayals. What is that judgment? Well, Nolan told the Times that J. Robert Oppenheimer is nothing less than “the most important person who ever lived.” His film says the same thing. It will second-guess decisions and policy. It won’t second-guess the man. It says this person played god more than any other human.

But did he? Nolan concedes that his “most important” tag for Oppenheimer is debatable; “in Hollywood, we’re not afraid of a little hype.” One counterargument to that “hype” is that other kinds of weapons, not just atomic ones, had greatly accelerated the pace of killing from the scenes in, say, “Napoleon,” another 2023 film. Machine-guns. Fighter jets. Aircraft carriers. Oppenheimer built the bomb but did not decide where it would be detonated. Nolan has high regard for Oppenheimer’s impact. But he never declares what his movie means.

What certainly appealed to Nolan is Oppenheimer’s connection to the greatest forces of the universe. Not just to atomic blasts, but theoretical science. In his Berkeley classrooms, Oppenheimer could hardly depict the formation of a black hole, but Nolan can easily do that by projecting the galactic explosions and fireballs in Oppenheimer’s mind, with the occasionally haunting soundtrack that will make you wonder, at moments, how tiny and delicate human life seems in all of this cosmic commotion.

That might be a grim revelation. But Cillian Murphy, as the scientist, approaches the pursuit of physics, as well as his own downfall, with wide-eyed wonderment. A goal. A job. A discovery. From some angles, Murphy, who is Irish, strongly resembles John F. Kennedy, from the ’50s when Kennedy was skinny, the future decision-maker in the world’s (still to this day) greatest nuclear drama. Certain values are unimpeachable. Others, particularly domestic ones, a subject that “Oppenheimer” sort of wants to explore and then really doesn’t, negotiable. Truths are not to be feared. The A-bomb is simply a way station, an incredibly rare convergence of public need and theoretical science. After this, we can know more about black holes and star creations and time and maybe ... what it all means.

That is the scientific calculation many would agree with. What’s intriguing is that Oppenheimer the politician is probably more effective than Oppenheimer the scientist. We have to do this program, he will conclude, because hostile peoples in the world are also going to do it, and whoever gets it first will play god. That will be the prevailing view throughout the film. Does it seem as though the world’s leading physicists in the 1940s were all a bunch of bombmakers? It would be reassuring to think they could unite for other reasons.

More than once, J. Robert Oppenheimer will note that his own people are extinction targets. But it could be anyone. Imagine the Nazis with such a weapon. Nolan interestingly sets aside the issue of a Jewish scientist leading this project except for one critical angle: motivation. Oppenheimer will take the job to defend people. Did Leslie Groves approach other leading physicists who were not Jewish and simply didn’t see the urgency or necessity for such a bomb or were unwilling to put themselves through such an endeavor? The movie, only through dialogue, implies that Oppenheimer was chosen not for ethnicity, but stature.

One character gently mocks Oppenheimer as “The Great Salesman of Science.” But Oppenheimer is such a good salesman, people want the product even if they possibly don’t need it. Well into the Manhattan Project, the Nazis are reeling. Defeated. Atomic weapons are not needed to stop them. Japan is still engaged, barely. But it’s dying, can’t win. Yet the Project continues, for any number of reasons — saving American troops’ lives, sending a message to the next Hitler, keeping the Soviets at bay, plain old self-defense.

The pinnacle of the film is the successful test at Los Alamos. That makes J. Robert Oppenheimer significant. He becomes a lot more significant if this weapon is actually deployed, and he knows it, and this is some level of tragedy. Nolan puts Oppenheimer in what looks like a little basketball arena, celebrating the success of the blast with the people of his Los Alamos community. The moment contains a blend of mid-’70s films “Hearts and Minds” and “Save the Tiger,” in which war is partly depicted as a spectator sport in the former, and the protagonist while attempting to speak sees the ghostly maimed faces of World War II in the latter.

“Oppenheimer” undoubtedly is a Western. Many times the protagonist will be seen in a hat, brim pulled slightly down in front, a bit like the Marlboro Man. “Oppenheimer” is authentically New Mexican, where the real scientist really spent time before the Manhattan Project was based there. Nolan portrays the land as remote, neutral, lovely, but not delicate. The testing being done on these grounds will not despoil this environment. It is the appropriate venue for this type of work, even if the film alarmingly reminds us of how these devastating weapons were tested on American soil with people in proximity.

“Oppenheimer” is the other half of a much-earlier movie, 1970’s “Patton.” That movie is the strongest implication that the 1940s brought the end of the generalissimo, whose tank-led arsenals will gradually be replaced by geniuses pushing buttons. Note what’s never shown in “Oppenheimer” — Pearl Harbor, Bataan, the death camps, the Battle of the Bulge. Those are the collective arguments, strong ones, for the activity in “Oppenheimer.”

The backstory of “Oppenheimer” is spare. The movie assumes viewers know at least the beginning and end of World War II. Not portraying that material helps Nolan keep a fast pace through nearly three hours of often-bureaucratic material. But does that lack of backstory unfairly taint the motives of the scientists? They are seeing, but viewers are not seeing, daily news articles of Americans and Allies drafted and dying in this war, and cities (especially on the West Coast) turning out the lights every night out of fear of an aerial bombardment. Japan is quietly implied throughout the movie as a non-threat, mostly irrelevant. At times, “Oppenheimer” will feel like a bunch of academics treating their weapon, and its potential targets, like a science experiment.

Underlying the final third of “Oppenheimer” is the implication that, once the war is done, military heroes are expendable. Other World War II figures are not mentioned (save for JFK), but MacArthur was fired; so was Churchill. “Oppenheimer” allows that the various rivals, adversaries or outright villains of this film, the Salieris to the Mozart, may be correct, on some levels, about policy, that the protagonist is someone who deals with scientists not heads of state and freely admits that there are many tough questions about his product and which peoples it may be safely used with. The protagonist will repeatedly push the notion that, Well, now that we dropped The Bomb, we can just get the Soviets and everyone else to agree not to drop any more of them. That outcome, so far, has been achieved, but apparently more by luck than the U.N.

Charles Lindbergh, whose heroic acclaim unraveled actually just before American involvement in World War II because of his prominent isolationist stance, is a curious contrast with J. Robert Oppenheimer. Lindbergh’s feat was private enterprise. The government had nothing to do with it. Oppenheimer? The government had everything to do with it. It chose him. It gave him the resources. It (mostly) made the rules. Is “Oppenheimer” a subtle argument in favor of government programs? A Soviet spy was handed a front-row seat to the project. Bad decisions may — may — have been made about sharing, or not sharing, information. The most we can conclude from “Oppenheimer” is that government mostly had it right but did not know how to deal with its own success.

The final hour of “Oppenheimer” is the tragedy, one inflicted not by petty rivals but conscience. A man delivered a beyond-Nobel-standard scientific achievement yet never won a Nobel. He confesses to President Harry Truman that his accomplishment makes him feel like he had blood on his hands. What, precisely, stokes the guilt? It is not, according to the movie, simply attacking the enemy. Many others built weapons, deployed weapons, used weapons. The firebombing of Tokyo is mentioned in the film. German cities were leveled also. For Oppenheimer, it is the numbers. The five- or six-digit numbers from two cities. That is why this giant of the mountains will shirk in a tiny room and listen to himself be humiliated, because he’s afraid he maybe deserves it.

This is Nolan’s triumph. Throughout human history, most governance has been brutal. Strongmen, thugs. 120-pound J. Robert Oppenheimer is the ultimate badass. This movie is about what happens when a society listens to its thinkers, not its thugs. It’s us or the Nazis.

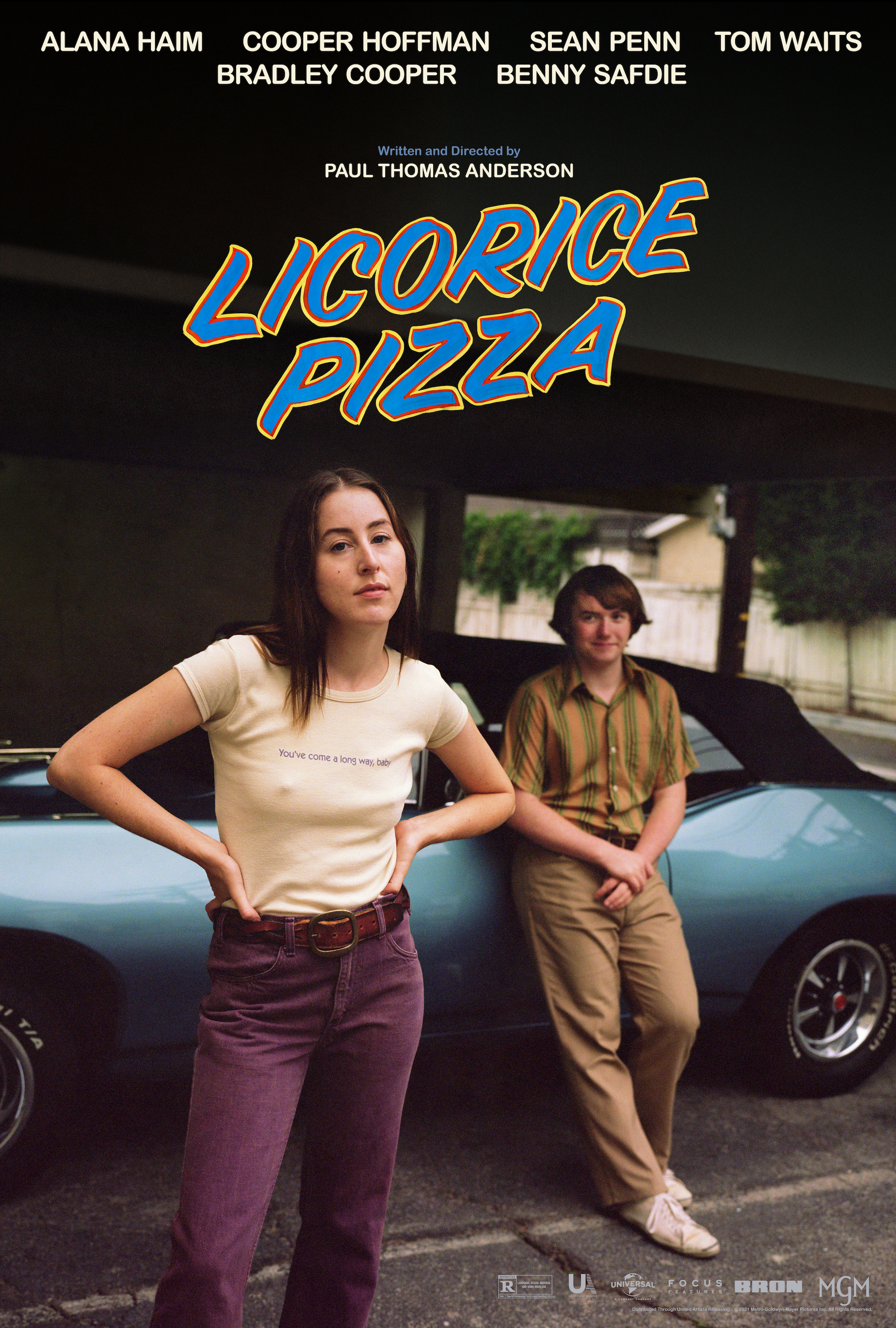

The most interesting frenemy of Oppenheimer is Edward Teller, played by Benny Safdie, the director/actor who nearly stole the show in “Licorice Pizza.” Nolan creates a Salieri-Mozart type of professional debate involving hydrogen/“Super” and fission/fusion that is too dense for what Nolan wants to portray. But enough of a point is made — Teller in the film is a burly, stubborn hothead who’s difficult but whose contributions are important. Oppenheimer elicits the contributions, and a payback, which is accepted with a handshake.

Several times in the film, Nolan depicts what he sees as the scientific world’s transition from Einstein to Oppenheimer. These scenes too closely resemble those of “The Godfather,” when the retired Vito pokes around his garden offering a few bits of sage wisdom to Michael. The Einstein conversations disappointingly fail to give the story much lift; his strongest warning is about awards ceremonies. There is a sad little implication here, that elite brainpower, just like athletic skill, declines at advanced age, that the person regarded as the world’s smartest is no longer capable of what Oppenheimer is doing. It may be that Einstein refused to take part in the Manhattan Project on pacifist grounds. Yet he took part in the warning letter to Roosevelt — not about pursuing the project, but not pursuing the project.

Einstein is most valuable in “Oppenheimer” as an endorsement. If Albert respects him, so can everyone else. And they did. Careful being a centrist. They come at you from all directions.

4 stars

(December 2023)

“Oppenheimer” (2023)

Starring

Cillian Murphy

as J. Robert Oppenheimer

♦

Emily Blunt

as Kitty Oppenheimer

♦

Robert Downey Jr.

as Lewis Strauss

♦

Alden Ehrenreich

as Senate Aide

♦

Scott Grimes

as Counsel

♦

Jason Clarke

as Roger Robb

♦

Kurt Koehler

as Thomas Morgan

♦

Tony Goldwyn

as Gordon Gray

♦

John Gowans

as Ward Evans

♦

Macon Blair

as Lloyd Garrison

♦

James D’Arcy

as Patrick Blackett

♦

Kenneth Branagh

as Niels Bohr

♦

Harry Groener

as Senator McGee

♦

Gregory Jbara

as Chairman Magnuson

♦

Ted King

as Senator Bartlett

♦

Tim DeKay

as Senator Pastore

♦

Steven Houska

as Senator Scott

♦

Tom Conti

as Albert Einstein

♦

David Krumholtz

as Isidor Rabi

♦

Petrie Willink

as Dutch Student

♦

Matthias Schweighöfer

as Werner Heisenberg

♦

Josh Hartnett

as Ernest Lawrence

♦

Alex Wolff

as Luis Alvarez

♦

Josh Zuckerman

as Rossi Lomanitz

♦

Rory Keane

as Hartland Snyder

♦

Michael Angarano

as Robert Serber

♦

Dylan Arnold

as Frank Oppenheimer

♦

Emma Dumont

as Jackie Oppenheimer

♦

Florence Pugh

as Jean Tatlock

♦

Sadie Stratton

as Mary Washburn

♦

Jefferson Hall

as Haakon Chevalier

♦

Britt Kyle

as Barbara Chevalier

♦

Guy Burnet

as George Eltenton

♦

Tom Jenkins

as Richard Tolman

♦

Matthew Modine

as Vannevar Bush

♦

Louise Lombard

as Ruth Tolman

♦

David Dastmalchian

as William Borden

♦

Michael Andrew Baker

as Joe Volpe

♦

Jeff Hephner

as Congressman

♦

Matt Damon

as Leslie Groves

♦

Dane DeHaan

as Kenneth Nichols

♦

Olli Haaskivi

as Edward Condon

♦

David Rysdahl

as Donald Hornig

♦

Josh Peck

as Kenneth Bainbridge

♦

Jack Quaid

as Richard Feynman

♦

Brett DelBuono

as Concerned Scientist

♦

Benny Safdie

as Edward Teller

♦

Gustaf Skarsgård

as Hans Bethe

♦

James Urbaniak

as Kurt Gödel

♦

Trond Fausa

as George Kistiakowsky

♦

Devon Bostick

as Seth Neddermeyer

♦

Danny Deferrari

as Enrico Fermi

♦

Christopher Denham

as Klaus Fuchs

♦

Jessica Erin Martin

as Charlotte Serber

♦

Ronald Auguste

as J. Ernest Wilkins

♦

Rami Malek

as David Hill

♦

Máté Haumann

as Leo Szilard

♦

Olivia Thirlby

as Lilli Hornig

♦

Jack Cutmore-Scott

as Lyall Johnson

♦

Casey Affleck

as Boris Pash

♦

Harrison Gilbertson

as Philip Morrison

♦

James Remar

as Henry Stimson

♦

Will Roberts

as George C. Marshall

♦

Pat Skipper

as James Byrnes

♦

Steve Coulter

as James Conant

♦

Jeremy John Wells

as AAF Officer

♦

Sean Avery

as Weatherman

♦

Adam Kroeger

as Army Captain

♦

Drew Kenney

as Soldier

♦

Bryce Johnson

as AAF Officer 2

♦

Flora Nolan

as Burn Victim

♦

Kerry Westcott

as Laughing Woman

♦

Christina Hogue

as Kissing Woman

♦

Clay Bunker

as Kissing Man

♦

Tyler Beardsley

as Weeping Man

♦

Maria Teresa Zuppetta

as Consoling Woman

♦

Kate French

as Presidential Aide

♦

Gary Oldman

as Harry Truman

♦

Hap Lawrence

as Lyndon Johnson

Directed by: Christopher Nolan

Written by: Christopher Nolan (screen)

Written by: Kai Bird (book)

Written by: Martin Sherwin

Producer: Christopher Nolan

Producer: Charles Roven

Producer: Emma Thomas

Co-producer: Andy Thompson

Executive producer: Thomas Hayslip

Executive producer: Helen Medrano

Executive producer: J. David Wargo

Executive producer: James Woods

Music: Ludwig Göransson

Cinematography: Hoyte Van Hoytema

Editing: Jennifer Lame

Casting: John Papsidera

Production design: Ruth De Jong

Supervising art director: Samantha Englender

Art direction: Jake Cavallo, Anthony D. Parrillo

Set decoration: Claire Kaufman, Adam Willis, Olivia Peebles (New Nexico unit)

Costumes: Ellen Mirojnick

Makeup and hair: Jaime Leigh McIntosh, Luisa Abel, Heidi Baca, Ashley Rae Callahan, Julie Callihan, Renee C. Caruso, Maiko Chiba, Rebecca Cotton, Leslie Devlin, Christy Falco, Lydia Fantini, JT Franchuk, Rheanne Garcia, Celeste Gonzalez, Glen P. Griffin, Jason Hamer, Meghan Heaney, Jamie Hess, Bia Iftikhar, Kerrin Jackson, Jennifer Jane, Jamie Kelman, Todd Kleitsch, Brittany Lester, Ahou Mofid, Jason Chandler Pettus, Rob Pickens, Andrea Steele, Teresa Stone, Hanny Tjan, Sheila Trujillo, Danielle Vigil, Hiro Yada

Post production supervisor: Tina Anderson

Production supervisor: Amiee Clark

Production manager: Shelagh Conley

Unit production manager: Thomas Hayslip

Unit production manager: Nathan Kelly

Stunts: George Cottle, Anthony Genova, Dean Bailey, Steve DeCastro, Danny Downey, David Elson, Duffy Gaver, Owen Holland, Terry Jackson, Derek Lacasa, Josh Lakatos, Nick LaRocca, Richard Lippert, Mark Norby, Jolene Van Vugt

Thanks: Kai Bird, Robbert Dijkgraaf, Senator Patrick Leahy, David Saltzberg, Lee Sandberg, Martin J. Sherwin, Kip Thorne