Whatever direction they go in ‘Licorice Pizza,’ Gary’s pursuit of Alana needs a gallon of gas

You can’t help but think that maybe Alana can do better.

She owns “Licorice Pizza.” Every scene. Yet she falls for a 15-year-old hustler whose contributions to the world are every bit as uncertain at the movie’s ending as at the beginning. Maybe that’s what director Paul Thomas Anderson is trying to say — when we know we’ve made the right choice, we accept the bad with the good.

It’s also possible that Anderson, similar to Quentin Tarantino’s “Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood,” is simply trying to say that the early 1970s were awesome, and he had to create a shaky Alana-Gary romance to backfill his way through this nostalgia called “Licorice Pizza,” a film named after an L.A. music store of the ’70s and curiously more interested in its fabulous soundtrack than its characters are.

Unlike Tarantino, who clumsily attempted to dovetail an uninteresting midlife crisis with the devastating Sharon Tate case, Anderson has smartly invented a quirky love story that doesn’t have to match up with a notorious incident. A high school boy is pursuing an older girl (“woman” is the correct term). The younger person in this coupling is focused and determined, while the older person is immature and still waiting to find herself.

Can this pairing work? It seems the odds are against them, and Anderson. Alana’s final quote does not feel earned. It’s like the referee deciding that, after 99-99 in the second overtime, one of the teams is supposed to win and thus awarding the game to them. That observation is a critique of plot development. It’s not an indictment of Anderson’s work. “Licorice Pizza” is inspired, funny, and packs a powerful statement.

Nearly overwhelming “Licorice Pizza” is the light.

Every daytime window is bathed in almost heavenly glare, Bergman-like, but none as much as the school grounds in the opening sequence. Anderson is most associated with Robert Elswit’s photography. This time, Anderson is the credited cinematographer with Michael Bauman, who’s had gaffer gigs on a host of well-known films, including “The Bling Ring” and “Nightcrawler” (the latter being another film in which an older woman curiously accepts a dinner invite from a quirky, enterprising younger man). The brightness is not unlike window treatment in other Anderson films but at sharper magnitude, a stark contrast to the richness of Tarantino’s film, a dry effect. Many movies, at a character’s low point, throw in some rain. “Licorice Pizza” doesn’t bother with precipitation. We see daytime images of hard work, inspiration and unlimited potential. The setbacks happen at night, when the chickens come home to roost.

In that opening sun splash, Anderson modestly flexes his enormous talent. Notice the motion. On a long school sidewalk, Gary and Alana initially walk in opposite directions. She’s going against the grain. Then she’s noticed by Gary. And suddenly, they’re going the same direction, left to right. They must be passing people in line, but those other people cease to matter. That alone would be effective. Anderson raises the scene to art form, flipping the camera — but not the actors ... or is he? — the moment Gary has impressed Alana. Gary asks “Did you see ‘Under One Roof’?” and she responds “Yeah.” Now they’re going right to left, this emerging couple together against the grain.

“L’Avventura” is famous in part for how Antonioni flips the direction of Monica Vitti among the rocks while her friend is missing. If you study Anderson’s scene, you’ll note the background before and after the flip seems similar. Are they walking down the center of a symmetrical courtyard ... or is Anderson just having a little fun?

He’s surely having some fun, and paying a nice tribute, when just moments later, Gary’s in a high school bathroom combing his hair when some prankster explodes something in a toilet, prompting the boys to bolt out of there just as Ron Howard did during the “At the Hop” performance in “American Graffiti.” In another tribute, the green font of opening credits in “Licorice” also matches that of “Graffiti.” (That movie by the way was made in 1973, about the 1960s.)

Almost as inescapable as the light is the running. Once Gary or Alana starts hightailin’ it, we know someone’s falling for someone, even if they can’t say it.

Alana Haim, a musician who had never been in a movie, joins the short list of Staggering Debuts By An Authentic Amateur that suggest film typecasting may be more important than training. There was the boy Benoit in the Quebec classic “Mon Oncle Antoine,” played by a local kid, Jacques Gagnon, a “natural” who was picked up as a hitchhiker, but Haim’s staggering performance might be compared to that of Pierre Blaise, the unknown cast as the lead in 1974’s “Lacombe, Lucien” who somehow carried that all-time great film on his back.

One hilarious moment spurred by Haim’s instinct occurs when Alana slaps Gary. She has hastily returned to his home after a disagreement, asking, “Do you really want to see my boobs?” Of course we know his answer. A follow-up question from Gary prompts her sudden reaction. Haim told Vogue that the slap was “not in the script” and was “my idea” and her co-star was “completely caught off guard.”

That Haim is in a band is ironic, given that a major shortcoming of “Licorice Pizza” involves music. Why didn’t Anderson make Alana a part-time singer? His soundtrack is superb. But Anderson’s missing the kind of signature live number that “Graffiti” boasts in “At the Hop,” performed by Flash Cadillac & The Continental Kids (the band in the movie is labeled as the fictional Herbie & the Heartbeats). Two ’70s hits will resonate in “Licorice Pizza”: “Stumblin’ In” and “Let Me Roll it.”

Anderson knew Haim and her family from a young age and directed Haim and her sisters in band videos. Little did the Haims realize they were in effect auditioning for (or inspiring) something much bigger. Obviously Anderson saw something about Alana that was proven right by this film and admits “The movie was written for her.” Of course it was; “Alana Kane” is as much Alana Haim as “Jerry Langford” is Jerry Lewis in “The King of Comedy.” Anderson wisely lets Haim be rather than try to act out this very limited character. Irresistible moments abound, such as Alana sensing disapproval and chasing her sister around the home (“You THINKER!!!”), or introducing herself to Gary’s friend Sue (she is actually so smooth in this exchange that maybe she’s had this kind of conversation previously), or confronting the man in the No. 12 shirt outside the campaign office (with a creative face-to-face side angle from Anderson). Perhaps her funniest, strongest scene is the look on her face — fall-off-the-couch bewilderment — when Jon Peters is asking Gary questions.

Proof that show business is tough for newcomers, Haim somehow didn’t receive an Oscar nomination even though “Licorice Pizza” earned three in some big categories — Picture, Director and Original Screenplay. Had Haim scored a nomination ... talk about going against the grain ... she would’ve been facing The Establishment. Jessica Chastain (“The Eyes of Tammy Faye”) won Best Actress, besting the formidable field of Kristen Stewart, Penélope Cruz, Olivia Colman and Nicole Kidman, probably none of whom meant to their films what Haim meant to hers. Anderson lost Best Picture to “CODA,” Best Director to Jane Campion (“The Power of the Dog”) and Best Original Screenplay to Kenneth Branagh (“Belfast”).

Intentional or not, “Licorice Pizza” parallels the drama in “Once Upon a Time...” and other Tarantino films, albeit junior-sized. Characters are having a crisis about aging. Gary, according mostly to what is stated (that’s a negative) but also by what is shown at his auditions and the Lucille Ball-esque variety show (those are positives), was a prolific and talented child actor who is now simply too old and too big (physically) to achieve the same success. The death knell to Gary’s acting career is delivered by a funny frown from the casting character played by Maya Rudolph, who is Anderson’s significant other. Is Gary depressed by this unfolding situation? Not at all. Unfortunately, this is a lapse in Anderson’s script. Gary boasts in the early scenes about being a natural actor, but most of the movie is about his dubious business ventures. He doesn’t miss the acting scene. Nor does he yearn to be older. At 15, he does virtually everything an adult does.

He’s free to move on to other things that interest him more, although why they interest him more is never illustrated by Anderson. Gary doesn’t seem motivated by money, or moving into elite social classes, or partying. He’s got connections in Hollywood but prefers to hang out with nobodies and restaurateurs. Unlike Rick Dalton in “Once Upon,” he embarks on his business ventures not out of desperation, but anticipation. Rick is a conformist who wallows in self-pity; Gary’s a rebel who enjoys sticking it to anyone who tempts him, which isn’t exactly a great attribute for a businesman. Rick’s story is the more traditionally sound. Gary’s is potentially more exciting.

Alana is not really too old for anything except for Gary. He is lumpy and unkempt, but his age is her hesitation. By hanging out with Gary, is she subconsciously attempting to be a teenager forever? Does she share in late-night conversations with her sisters any fears that life will be over at 30? All we know is that she has a habit of bumping into kids on sidewalks and cursing them. She cares not about what neighborhood Gary lives in or whether he’s going to Stanford. While Gary’s backstory is limited, Alana’s is nonexistent. She has no friends. Was she a homecoming queen contender, or did no one ask her to the prom? Did she get A’s or D’s? Is she troubled ... enough ... by the realization that the male who may want her the most may fail important demographic tests? A tough question for Anderson.

As Gary, Cooper Hoffman, the son of late Anderson regular Philip Seymour Hoffman, fails to make the case, but he’s got his moments. His best is when he’s attempting to resume work as a child model and demonstrates the various ways a kid can wear a Sears suit. He also fields the spree of questions from Jon Peters with glorious deadpan responses. It’s when Gary gets chippy and sabotages or exploits things that he’s not funny, and audiences may wonder why they should be rooting for this person.

Gary Valentine is based on Gary Goetzman, a onetime child actor-turned-adult-actor-and-entrepreneur-and-Hollywood producer associated with Tom Hanks projects. A friend of Anderson, Goetzman has a credit in the quirky, interesting, but not particularly great “Melvin and Howard.” No doubt, Goetzman has led an incredible life with surely incredible stories. Anderson may have been too smitten with those stories and thought they could carry much more than they do. Scattered around among vignettes, Hoffman never nails what it is that makes Gary tick.

Even the characters in “Pretty Woman” are vulnerable. That’s why that movie works. Is there any vulnerability in “Licorice Pizza”? Well, no. These are young misfits who thrive on tweaking the establishment. They’re destined to do it together. No one’s really afraid of anything. The only person who ever makes Gary turn serious is the guy playing the pinball machine by leaning into it (a hilarious scene as Gary protests and gives up). That’s a problem for a movie about an ambitious romance.

Roger Ebert wrote endlessly of the “Meet Cute.” Usually, it takes a few scenes. “Licorice Pizza” wastes no time, as Gary discovers Alana at his high school as the film begins. We’re only five minutes in when Gary announces the mission of the remaining couple hours: “I met the girl I’m gonna marry one day.”

Gary’s move is bold, but Anderson’s is bolder. Instead of warming up a plot for 30 minutes, he is outlining, immediately, where his characters are in life and what’s going to happen in the end. That leaves a lot of drama to fill in to get us to the ending we’re assured of. Along that arc, “Licorice Pizza” will become episodic, less a story progression than a collection of “SNL”-like skits.

In “The American President,” the audience roots for a skeptical woman to come around to the idea of dating a man of higher stature. In “Licorice Pizza,” Alana is hooked, somewhat, way too soon. With Gary locked in, it’s up to Alana to play the field. The first three of her other male acquaintances, all SoCal VIPs, are made because of Gary. All three of these encounters end disappointingly in strange ways (the child actor Lance seems to get a raw deal), prompting Alana to suddenly commit herself to do-gooder politics, only to conclude that Gary is the one who deserves her vote. Does it add up? Not really, but it’s a fun campaign.

The only time “Licorice Pizza” turns serious is just before the ending. The idea of a closeted gay politician, while certainly occurring in the ’70s, is not one of the decade’s motifs like waterbeds and gas lines and pinball. It’s there for a couple of reasons, to provide Alana with a final hurdle before running to Gary and to remind us that nostalgia for the good ol’ days tends to sweep aside the conditions that weren’t so good.

Anderson cleverly introduces Joel Wachs in an interview making a statement no one believes — that he has no time for dating — and the viewer knows we will either find him hitting on Alana or facing a whisper campaign. Wachs is a real person whose career in fact closely resembles that of the character. Goetzman worked for him. (That’s a departure from the script, of course, as it’s Alana, not Gary, who volunteers.) Wachs consulted with Anderson and suggested changes for accuracy (that might be the 1973 mayoral campaign ... Anderson says Wachs thought Goetzman filmed the mountain ad, but it was really Jonathan Demme ... Wachs was a Republican, a word that you won’t see or hear in the movie nor in this recent L.A. Times profile.). He says some of the character is Anderson’s “artistic creation as a writer.” He says at the time, “I never said I wasn’t gay.” Wachs is played by Benny Safdie, a natural who directed Adam Sandler in the frenetically watchable “Uncut Gems.” He is by far the most interesting of the “Licorice Pizza” supporting cast. Hero, victim, or villain? We wouldn’t think the latter except for Anderson’s exceptional camera positioning at that restaurant, in which we hear Joel’s directions offscreen and his tone of voice and start to envision less an idealist ... and perhaps a manipulator. “I never had a boyfriend at that time. That boyfriend is fictional,” says Wachs, who notes more artistic license by Anderson: “I’m not disorganized.”

Maybe the film’s most perfect character is Brian, the smooth staffer for the Wachs campaign played by Nate Mann. He seems to know things about the councilman and the business that Alana doesn’t, but that tempers only his enthusiasm, not his professionalism. Alana calls him as though she were asking him for a date, but his appearance comes too late in the film to create an engrossing dilemma for her (Anderson weakly has them appear to come close to kissing at an empty office, interrupted by a Wachs phone call), so his is the abridged version. They have some history that they can both chuckle about. When he offers to take her to see Wachs, she gets extremely defensive, overreacting to his helpful offer as though fearing he will disrupt whatever moment she is about to share with Wachs. Brian has seen Alana’s kind too many times before, the starry-eyed volunteer who doesn’t know the reality of the business and won’t be long for this industry.

There should be surface-level cynicism in “Licorice Pizza,” but Anderson, to his credit, doesn’t allow it, and the movie doesn’t feel compromised without it. Yes, a person with the self-confidence of Gary has possibly made similar vows to other girls. No, Gary doesn’t demonstrate the kind of wealth or connections or even business aptitude that would allow him to keep opening retail stores at 15 or 16, especially when his time is clearly needed in his PR ventures. Yes, Alana may be way behind on her credit cards. That doesn’t matter. What matters is that Anderson fails to give viewers a need to see this couple together.

In Gary’s first big conquest, Alana actually shows up for the “date” that he suggested. It would be better if, before this scene happens, the characters were shown going about their daily routines and Alana’s appearance at the Tail o’ the Cock came as more of a surprise. Convincing an incredible girl just to go on a date with you is an immense challenge for a boy. Now that Gary has succeeded, what else is needed? To paraphrase Johnny Mathis and Deniece Williams (whose late-’70s hit is not heard on this soundtrack), it’s Too Much Too Soon, Too Little Too Late.

Anderson in 2019 gushed about “Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood,” and there’s no question “Licorice Pizza” is cut from similar cloth. It’s two totally different stories but similar setting, a few years apart. Yes, there’s a difference between Benedict Canyon and the Valley, as illustrated in each film, but both are magnetically watchable, they are environments as much as they are movies. Turn them on, even in the background, soak in the vibe.

Both thrive on soundtracks. Anderson’s “Boogie Nights,” set in the Valley just a few years after “Licorice Pizza,” also boasts a great soundtrack. In that film, the music is complementary. Just as in “Licorice,” the “Boogie” lyrics are perfectly timely, but the “Boogie” songs almost detract from the very serious negotiations, arguments and lamentations that drive that story. “American Graffiti” and Cameron Crowe’s “Almost Famous,” which closely matches the era of “Licorice Pizza” as well as the notion of a teen boy doing adult-type work and mostly succeeding, are less about pinpoint lyrical accuracy and more about how generational tunes kind of grab us and never let go. Unlike “Licorice,” characters in those other films celebrate what they’re listening to. “Graffiti” and “Once Upon” both idolize automobiles and can’t show them enough. “Licorice,” interestingly, could not care less. Alana drives, a little, but we don’t know or care how Gary gets around.

One disappointment of “Licorice Pizza” is the wardrobe. “Once Upon” was far more successful in this category. Its clothing is exciting. Haim’s outfits are plain and forgettable. She did tell Vogue, “The dress I loved the most was the red one with the white collar. ... I looked like a doll.” Most would probably pick the bikini, in which Haim so modestly stuns. Gary is generally decked out in white pants and striped shirts, circa Beach Boys 1963. The costumes are credited to Mark Bridges — all he did was win an Oscar for the devastating outfits in “Phantom Thread,” and also for “The Artist.” This time, he comes up short.

In terms of Things That Raise Eyebrows, there were different standards in the 1970s. More than the ages of the two stars, it’s the portrayal of Japanese characters in “Licorice” that created the type of controversy that prompts talk about protests. These scenes in “Licorice” may illustrate the kind of stereotypes that were allowed in ’70s (and earlier) media, but the scenes are pointless and confusing (if he understands Japanese, why is he speaking to the women in English) and seem to be included only because very few non-white characters appear in this movie. Anderson largely ignored the criticism upon the movie’s release. It worked. There’s no indication he was ever ordered to change a scene or that the film was banned anywhere. (Then again, no one seemed to ask another relevant question, which is, Why is the Japanese restaurant even a part of this movie; what does it add?) Before the Oscars in March, Anderson sounded surprised that anyone complained about this portrayal, saying the complaints were “lost” on him.

Less noticeable is the gas-station tirade by the Jon Peters character as Paul Revere & the Raiders’ “Indian Reservation” plays. Peters encounters a person apparently of Native American ancestry at a pump and angrily declares it’s “Chumash territory” and, after hurling his gas can at the fellow, knocking him over, he grabs the pump and holds a lighter and asserts, “it’s my nozzle now.” White privilege couldn’t be more blatant. The Chumash are of Southern California and are the source of the name Malibu.

The courtship by a 15-year-old boy of a 20-something woman is the film’s separate controversy — as well as its hook. The critical view seemed to be that “this would probably never be a plot point in a major motion picture if the genders were reversed, but in Anderson’s hands the potential romance never feels creepy or exploitative.” That’s true — this type of artistic license is undeniably a one-way street.

Anderson’s film, most of the time, is snappy and funny. To fill the considerable space he has given himself, he indulges. The worst scene is likely the restroom conversation between Alana and a waitress in which the waitress reveals something cringe-inducing about Gary that the rest of the movie isn’t interested in. Alana’s “Jewish nose” casting interview is one interminable moment. Sean Penn’s motorcycle stunt — another strangely abrupt flattening of a possible big break for one of the characters — feels like it takes hours to get through (and surely would’ve required that much time for the restaurant patrons to set it up). The depiction of Gary being taken to the police station like a Guantanamo figure is bizarre and, like most scenes in this movie, is intended to show either Alana or Gary standing up for the other in a difficult time. It doesn’t make the LAPD look good, for sure, but given the utter lack of police in the rest of the film, including when cars are going the wrong way, windows are being smashed and riots are brewing at gas stations, it’s a strange check-the-box. There must’ve been a smoother way to show Gary in a legal scrape or the LAPD behaving badly rather than a head-scratching arrest that only leaves the audience wondering if they’ve missed something.

An exchange of phone calls between the two households’ living rooms is one of the movie’s weaker developments. Yes, this is a very important and very common hazard of dating or attempted dating — making a phone call and being unable or unwilling to speak. (That offense is even committed by the genius in “Good Will Hunting.”) Anderson adds a callback to an initially promising scene that becomes tedious.

Also tedious is the first “date,” in which Gary explains his family/business arrangement: He claims his mother works for him, and then, in a disappointing and ineffective crutch, begins to explain his business connections in a way intended to prepare viewers for those scenes but instead is just too much information and not absorbable this early in the film. And by the way, Alana never gets around to asking about Gary’s dad. (Gary orders Cokes at a restaurant like underage kids in movies do, evoking memories of “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.”)

Mother’s influence was a Hitchcock staple. Anderson is intrigued by parental relationships. In “Boogie Nights,” it is condemnation. Or perhaps a grievous mistake. Eddie’s mother assumes he has spent the night with a girl she does not like, when he has actually been auditioning for the crew that will launch him to fame. She declares him “stupid.” The ferocity of her alcohol-fueled tirade sends him literally running away toward a more receptive home.

Gary’s mother, like Eddie’s, is unaware of how far her son is getting along in the world. At the time “Licorice Pizza” begins, Gary has outgrown his mother. That becomes official when she is unable to chaperone his trip to New York. There’s a new candidate for that job. Gary may not need his mother’s opinion on whether Alana is the right girl. But does the audience? Anderson decides no.

A few geographies are so famous in the movies, people who’ve never lived there still sort of feel like they “get it.” The San Fernando Valley is one of those places. Like the Modesto of “American Graffiti” or the Bay Ridge of “Saturday Night Fever,” it’s a place in the vicinity of a crown jewel but decidedly outside the moat, where people with aspirations, determination or simple curiosity have to claw their way past the ham ’n’ eggers. Notice the celebs of “Once Upon a Time...” are 100% cool and desirable acquaintances, while in “Licorice Pizza,” they’re boorish buffoons, womanizing egomaniacs.

What does it mean that “Licorice Pizza” is set in the Valley rather than, say, Tulsa? The Valley’s close to celebs and movie stars who can drift in and out of Gary and Alana’s lives. But Tulsa has them too. You might be surprised. L.A. is simply Anderson’s hometown. “Licorice Pizza” takes place in the Valley for the same reason “American Graffiti” takes place in Modesto or “Risky Business” is set in Chicago’s lakefront suburbs. Call it home-field advantage.

Unlike in a lot of teenage comedies, Gary’s circle of friends/relatives is generic. By the end of the Jon Peters waterbed scene, you might even be wondering who these kids are. Sometimes they are shown yukking it up in the back of the truck, for reasons unclear. Years from now, you’ll see them as grownups in other films and exclaim, “He was in ‘Licorice Pizza.’” Evidently, we need to know that Gary has people working for him, and he specializes in cheap, round-the-clock labor.

How do we know Gary isn’t with the wrong sister? Were Gary to hit on Danielle or Este, that would be even more problematic in the minds of many than the age difference between Alana and Gary. The Haims are gorgeous. By giving the sisters a bit of screen time as message-takers and reliable observers, Anderson enhances the film’s authenticity but clouds the decision-making. Yes, Este and Danielle are older than Alana in real life; in the movie, they might as well be teenagers, and we all might as well wonder why in the world none of these stunning sisters has a date.

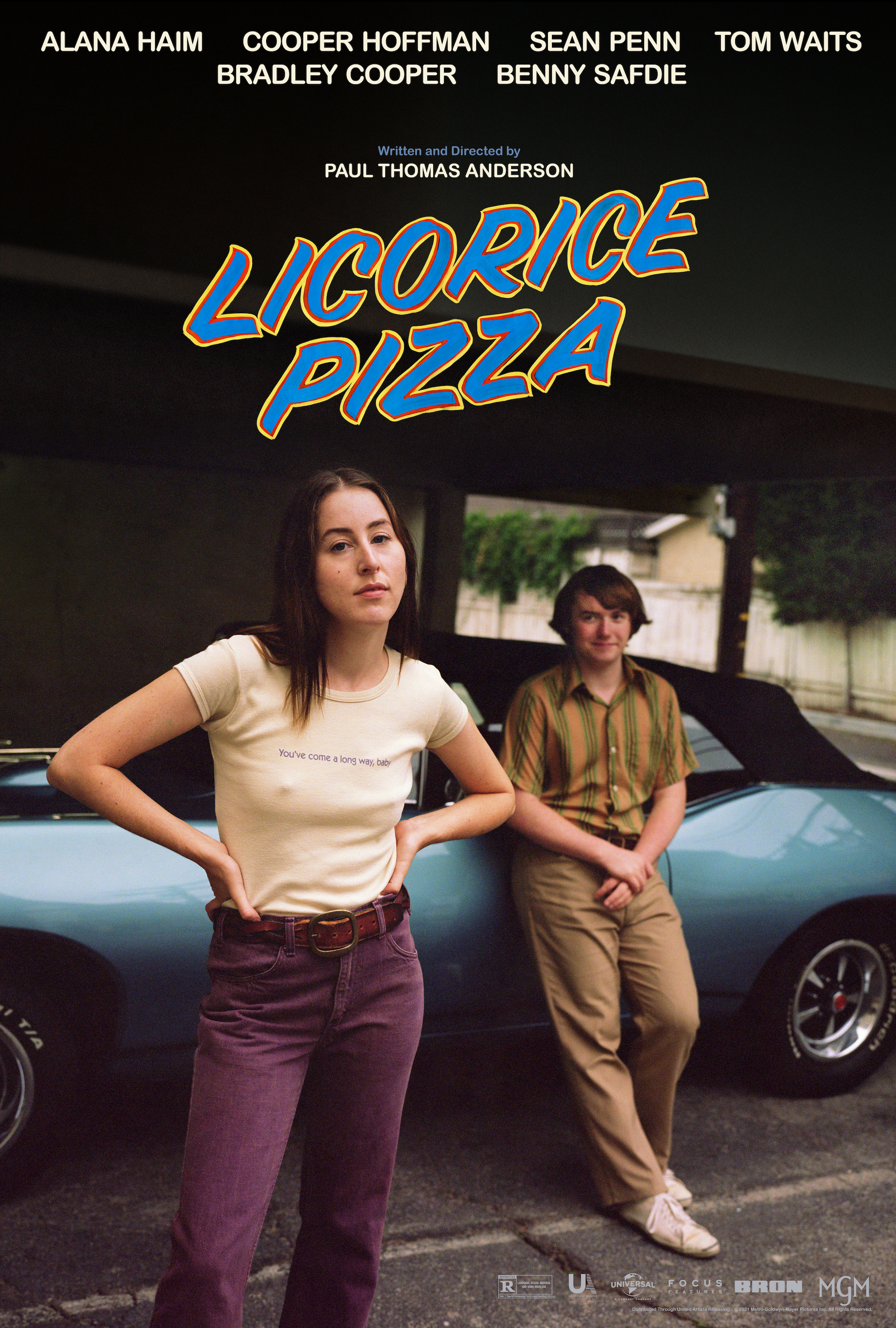

Publicity photos tell us a lot about what the director ... or producers ... or distributors ... sees in the movie. The most common poster image for “Licorice” shows Haim standing in front of a car, Hoffman in the background. A popular still photo is a shot of Haim and Hoffman running along a street near a field, together enjoying the freedom of a young life. The way you could do it in the Valley in the ’70s, play life by the ear, without a plan, bend some societal taboos and see what happens.

“Pretty Woman,” an undeniably great movie with different kinds of aspirations, shows us the kind of fire that can happen between the world’s hottest people. “Licorice Pizza” impressively tells us that physicality is not only less important, but irrelevant — that Alana and Gary will one day enjoy electrifying intimacy not because of how they look, but the moments they’ve shared, the chance she gave him.

According to the internet, Alana Haim, as of this writing, is not married. There’s going to be some really lucky Gary out there.

3.5 stars

(August 2022)

“Licorice Pizza” (2021)

Starring

Alana Haim

as Alana

♦

Cooper Hoffman

as Gary

♦

Will Angarola

as Kirk

♦

Griff Giacchino

as Mark

♦

James Kelley

as Tim

♦

Dexter Demme

as Cherry Bomb Kid / Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

River Cornwell

as Cherry Bomb Kid

♦

Harrison Bray

as Cherry Bomb Kid

♦

Sasha Spielberg

as Tiny Toes Girl

♦

Karissa Reynafarje

as Tiny Toes Girl

♦

Savannah Ioakimedes

as Tiny Toes Girl

♦

Dorie Samovitz

as Tiny Toes Girl

♦

Anna Cordell

as Tiny Toes Girl

♦

Adam Somner

as Tiny Toes Photographer

♦

Joshua Allen

as Tiny Toes Photographer

♦

Pat Hoelck

as Tiny Toes Photographer

♦

Colin Sutton

as Tiny Toes Photographer

♦

Lucia Angarola

as Grant High School Student

♦

Lola Brown

as Grant High School Student

♦

Nancy Cornwell

as Grant High School Student

♦

Harry Fincher

as Grant High School Student

♦

Laura Gary

as Grant High School Student

♦

Julie Goldklang

as Grant High School Student

♦

Ava Gosselaar

as Grant High School Student

♦

Lila Kay

as Grant High School Student

♦

Lucy Lopez

as Grant High School Student

♦

Zoe Novak

as Grant High School Student

♦

Van Rich-Takayama

as Grant High School Student

♦

Isaac Soren

as Grant High School Student

♦

Milo Herschlag

as Greg

♦

Phil Bray

as Don the Bartender

♦

Patrick Aranda

as Tail o’ the Cock Pianist

♦

Moti Haim

as Moti

♦

Donna Haim

as Donna

♦

Este Haim

as Este

♦

Danielle Haim

as Danielle

♦

John Michael Higgins

as Jerry Frick

♦

Yumi Mizui

as Mioko

♦

Mary Elizabeth Ellis

as Momma Anita

♦

Emma Dumont

as Airplane Brenda

♦

Skyler Gisondo

as Lance Brannigan

♦

Christine Ebersole

as Lucy Doolittle

♦

Andrew C. Eure

as Jerry Best Crew

♦

Joshua Zev Nathan

as Jerry Best Crew / Tilt

♦

Mia Bruno

as Jerry Best Crew

♦

Trevor Tavares

as A Jack

♦

Kathy Trinh

as A Jill

♦

Greg Goetzman

as Jerry Best

♦

Grace Anderson

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Ida Anderson

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Jack Anderson

as Under One Roof Kid / Jimbo

♦

Lucy Anderson

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Mahalia Flanagan

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Seamus Flanagan

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Tallulah Hoffman

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Willa Hoffman

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Megan Kelley

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Hudson Monkarsh

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Olive Monkarsh

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Stella Monkarsh

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Waylon Richling

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Ben Schacter

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Matty Schacter

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Hazel Schaffer

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

June Schaffer

as Under One Roof Kid

♦

Delaina Mitchell

as Stage Mom

♦

Liz Cackowski

as Stage Mom

♦

Vanessa Schacter

as Stage Mom

♦

Alex Monkarsh

as Stage Mom

♦

Tyler Young

as Audience Dad

♦

Josh Monkarsh

as Audience Dad

♦

Max Mitchell

as William

♦

Tim Conway Jr.

as Vic the Director

♦

Maya Rudolph

as Gale

♦

Erica Sullivan

as Director’s Assistant

♦

Iyana Halley

as Wig Shop Brenda

♦

George DiCaprio

as Mr. Jack

♦

Emily Althaus

as Kiki Page

♦

Brian Kehew

as Sonny & Cher Tech

♦

John C. Reilly

as Herman Munster

♦

Lily Munster

as Lily Munster

♦

Bottara Angele

as Fairgoer

♦

Laura Louise Richardson

as Fairgoer

♦

Lakin Valdez

as Cop

♦

Mark Kirksey

as Cop

♦

Allegra Clark

as Police Dispatch (voice)

♦

Craig Stark

as Long Haired Freak

♦

Ray Chase

as B. Mitch Reed

♦

Ingrid Sophie Schram

as B. Mitch Reed Assistant

♦

Ariel Rechtshaid

as KPPC Management

♦

Doug Weaver

as UPS Driver

♦

Megumi Anjo

as Kimiko

♦

Destry Allyn Spielberg

as Frisbee Kahill

♦

Ted McCarthy

as Waterbed Ted (voice)

♦

Lori Killam

as Janice

♦

Harriet Sansom Harris

as Mary Grady

♦

Coco Soren

as Lucy’s Friend

♦

Isabelle Kusman

as Sue Pomerantz

♦

Ray Nicholson

as Ray

♦

Austin Anderson

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

William Angarola

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Hudson Brown

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Sawyer Conklin

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Sylvie Conklin

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Sharyn Dent-Bray

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Renee Flanagan

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Jamie Giacchino

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Apryl Huntzinger

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Shana Dishell Richling

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Thomas John Rudolph

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Charlotte Schmid-Maybach

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Ford Stoller

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

George Stoller

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Theo Stoller

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

William Stoller

as Fat Bernie’s Waterbed Customer

♦

Sean Penn

as Jack Holden

♦

Dan Chariton

as Sam Harpoon

♦

Nathan M. Hadden

as Tail o’ the Cock Valet (as Nathan Hadden)

♦

Tom Waits

as Rex Blau

♦

Zoe Herschlag

as Wendi Jo

♦

Pearl Anderson

as Sharon

♦

Henri Abergel

as Henri

♦

Rogelio Camarillo Jr.

as Armand

♦

Eloy Perez

as Guillermo

♦

Theresa Anderson

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Mark Flanagan

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Joanne Gough

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Paul Gough

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Cassandra Kulukundis

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Danielle Miller

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Hank Oster

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Reina Reyes

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Kimiko Rudolph

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Richard Rudolph

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Kirk Saduski

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Katy Weber

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Dennis Weiss

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Mark Wolfson

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Ryan Young

as Tail o’ the Cock Patron

♦

Bradley Cooper

as Jon Peters

♦

Ryan Heffington

as Steve

♦

Benjamin Barrett

as Latin Lad

♦

Demelza Cronin

as Tennis Girl

♦

Katie Cronin

as Tennis Girl

♦

Nate Mann

as Brian

♦

Benny Safdie

as Joel Wachs

♦

Dennis McCarthy

as Reporter

♦

Mimi O’Donnell

as Reporter

♦

William Potter

as Joel Wachs Photographer

♦

Ted McCarthy

as Joel Wachs Chief of Staff

♦

Karen Kilgariff

as Joel Wachs Mom

♦

Alex Herschlag

as Joel Wachs Dad

♦

Madison Sonora

as Joel Wachs Volunteer

♦

Jonathan Goetzman

as Joel Wachs Volunteer

♦

Victoria Mae Kunkel

as Joel Wachs Volunteer

♦

Jon Beavers

as Number 12 Creep

♦

Luigi Della Ripa

as Luigi the Tailor

♦

Riley Parker

as Annoying Pinball Kid

♦

Max Beristain

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Eden Burakoff

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Alex Canter

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Avery Carey

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Aj Carr

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Angenaya Carr

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Nick Cohen

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Eric Culhane

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Astaria Dayne

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Mick Giacchino

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Luna Gray

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Julia Greene

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Sung Han

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Lawrence Haymes

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Arlo Reilly

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Francesca Sarracino

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Luigi Sarracino

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Frank Scott

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Max Scott

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Yanari Warren

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Ciara Williamson

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Hannah Williamson

as Fat Bernie’s Pinball Crowd

♦

Joseph Cross

as Matthew

♦

Louis Delavenne

as Rive Gauche Waiter

♦

Dan Anderson

as Encino Theater Staff

♦

Kat Barnette

as Ticket Taker

Directed by: Paul Thomas Anderson

Written by: Paul Thomas Anderson

Producer: Sara Murphy

Producer: Adam Somner

Producer: Paul Thomas Anderson

Executive producer: JoAnne Sellar

Executive producer: Daniel Lupi

Executive producer: Sue McNamara

Executive producer: Aaron L. Gilbert

Executive producer: Jason Cloth

Music: Jonny Greenwood

Cinematography: Michael Bauman, Paul Thomas Anderson

Editing: Andy Jurgensen

Casting: Cassandra Kulukundis

Production design: Florencia Martin

Art direction: Samantha Englender

Set decoration: Ryan Watson

Costumes: Mark Bridges

Makeup and hair: Heba Thorisdottir, Seana Chavez, Brian Kinney, Jacqueline Knowlton, Toryn Reed, Christi Cagle, Lori McCoy-Bell, Lori Guidroz, Julie Rea

Production supervisor: Demelza Cronin

Post-production supervisor: Erica Frauman

Unit production manager: Sue McNamara

Stunts: Brian Machleit, Craig Frosty Silva, Jeffrey Barnett, Shauna Duggins, Clay Donahue Fontenot, Kevin Foster, Jeremy Fry, Marilyn Giacomazzi, Sierra Hoyle, Rick Miller, Anthony Molinari, Robert Nagle, Chris Palermo, Jimmy Roberts, Charlotte Townsend, Greg Tracy, Tim Trella, Sera Trimble, Hayley Wright, Josh Yadon

Special thanks: Pam Abdy, Herbert Ault, Howard Berger, Carol Burnett, Grand L. Bush, Mike DeLuca, Jody Hamilton, Francette Kelley, Lori Killam, Donna Langley, Bryan Lourd, Robert Morse, Dan Sasaki, J. Randolph Schnitman M.D., Andrew Solt, Dustin Stanton, Roeg Sutherland, Joel Wachs, Scott Zimbler ... and Gary Goetzman

For: Robert Downey Sr. (a prince)