Apocalyptic? Decadent? Feminist? In any analysis of ‘Last Year at Marienbad,’ there’s a shadow of a doubt

He’s just not getting through to her.

“Last Year at Marienbad” is famous for what it lacks. Plot. Story. Conflict. Details.

So what do we witness? A man pursuing a woman. He is handsome, debonair, articulate. He provides her with plenty of evidence as to why they should be together. He experiences relentless frustration. She could accept or reject him but doesn’t. What is the reason she won’t embrace him? Has he gone mad? Is she married? Does she have amnesia? Has she simply changed her mind?

Well, that’s life. Sometimes, it doesn’t make any sense.

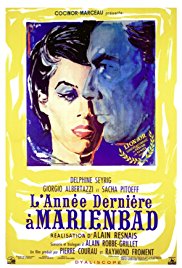

“Last Year at Marienbad” is considered something of a joint partnership between director Alain Resnais (pronounced “ReNAY”) and writer Alain Robbe-Grillet. It is Resnais’ second feature film. But there are strong indications of Auteur Theory, starting with the beautiful title, one of the greatest and most elegant in cinema.

Marienbad is a Czech spa community. It happens to be in the Sudetenland, a term forever associated with World War II. Another such term is “Hiroshima,” which is part of the title of Resnais’ first film. Perhaps he is telling us something about the apocalypse, or perhaps he is telling us that we are past the point of devastating conflict, a time when people will require new reasons to carry on.

Or perhaps he’s telling us neither. In a 2008 interview with film scholar François Thomas available on The Criterion Collection, Resnais explains that the original title was simply “Last Year” and that “Marienbad” was added later.

Reviewers offering numerous forms of analysis have found “Marienbad” (the French title is “L’année dernière à Marienbad”) to be enigmatic, dreamlike, unconventional, decadent, empty, surreal, mesmerizing, unwatchable. It can be called a horror film; others found occasion to laugh. The notion that the film could be a treatise of feminism is perhaps outlandish except that other attempted explanations also fall short. The protagonist is a male. His goal, in terminology of the time and prior, is to get the girl. Is he saving her or seducing her? He possibly succeeds. His obstacles are the woman’s own disbelief and then, as the arguments accumulate, another male who might be capable of killing at least one of them.

Delphine Seyrig, the gorgeous heroine of “Marienbad,” is elusive yet attainable. Seyrig was born in Beirut but spent some of her youth in New York and even attended the Actors Studio. Her “Marienbad” part presumably doesn’t require Method acting, an observation she apparently lamented to crew members, according to DVD commentary about the production. She’s a Bresson “model” in this picture, age 28. She is clothed by Chanel in 17 outfits, perhaps give or take one. Some are black, some white, some gray. The most beautiful is perhaps the X-back. Most of these will recur throughout the film in scenes suggesting both past and present.

According to the DVD commentary, Resnais was intrigued by the look of Louise Brooks in the 1929 Pabst silent film “Pandora’s Box.” He chose Seyrig over Anouk Aimée, then learned to his dismay that Seyrig had cut her hair. Out of necessity, she was given a wedge cut that became world famous.

Her suitor is Giorgio Albertazzi. Like Seyrig’s character, he is not named in the film. According to the published script, she is “A,” he is “X” and a second man, played by Sacha Pitoëff, is “M.” The three mingle at a baroque chateau among a well-dressed crowd who appear to be wealthy elites. Their apparent triangle serves as the drama. “X” may have shared a moment with “A” that “M” cannot match. But “X,” despite multiple attempts, cannot defeat “M” in a game of logic. In a shooting gallery scene, the film hints at a possible duel that does not come close to happening. “X” and “M” must settle this psychologically.

Judging by her elegance, “A” might be a socialite. It’s of course unknown whether she comes from the bourgeoisie. She could work professionally as a model or hostess. Prostitution is a fascination of filmmakers; practically every or every other Godard film of the ’60s dealt with it. There is no hint of a money exchange in “Marienbad,” but there are hints of control. The possibility of a marriage is suggested, but there is a lingering competition for a woman that is yet to be decided.

The film’s locations are real but not known to many Americans. Seeking a “baroque” environment, Resnais, according to crew members in the DVD commentary, could not find the necessary architecture in France, so the production booked famous palaces in the Munich area, with limited availability and considerable restrictions. Resnais will initially encase the film in a dark interior, cathedral-like motif, then gradually fan out in sunlight to the beautiful garden, site of the film’s signature visual, the shadows drawn on people but not trees. That famous garden, lined in the film by triangular bushes, is the “Grand Parterre” of Nymphenburg Palace. Another palace is the Amalienburg, built in the 1730s. These treasures somehow escaped devastation during World War II and provide some of history’s most powerful cinematography. The garden may be the path to life, but first, Resnais wants to embed us within the unyielding walls of decline.

As the camera scans ceilings, then doors and hallways, an opening narration fades in and out. A man speaks of walking on sand and stone, the long corridors of a “baroque” hotel, a “plush” carpet that absorbs sound, and a “bygone era.”

Many of the comments will repeat. We see a well-dressed and polite audience watching a play, called “Rosmer,” apparently a derivative of “Rosmersholm,” in which a male actor references the “long dead,” and “frozen” and “silent” faces watching a woman in hotel hall. A bell dings, almost like the end of a hypnotic state, and an actress tells him, “I am yours,” ending the play. The actress’ makeup expresses an edge and bears some resemblance to the look of Liv Ullmann performing “Electra” years later in Bergman’s “Persona.”

The audience comes to life, barely, as the play ends, and the camera finds a prominent blond woman, who seems initially as if she may be the story, “A” inconspicuously in the background. Resnais’ cameras will slowly begin to introduce “X” and his narration and “A.” Around the 18-minute mark, they will converse, dance, and she will finally speak.

The guests at the hotel ... are they having a good time? Old money or nouveau riche? The characters seem to be taking part in some kind of ancient rite that was once vibrant but is no longer relevant. “Marienbad” is contingent on neutrality. There are strong hints of decadence, but no one is getting drunk, and there are no signs of debauchery. In some way, the characters represent the French colonialists in the restored scenes of “Apocalypse Now” who seem to think their plantation way of life will continue forever. It becomes clear Resnais does not want to draw attention to his extras, but he needs them to acclimate the viewer to the abundance of mirrors and spatial disorientation that will mark the conversations between “X” and “A.” Some of the characters’ lips are moving, but no words are heard. The initially prominent blonde will turn, and her clothing and background will suddenly change as she maintains the pose, an effect used regularly in the latter parts of the film with “A.”

Notice what seems to be missing. Is there any electricity in this place? The lamps appear to be gaslights, although a few table lights could be from Vegas. How is the place heated? No one seems to be cold, and garden scenes suggest it is summertime.

Something else not seen is smoking, even though ashtrays are visible on tables. According to DVD commentary from crew members, use of the palaces came with restrictions on heating because of the sensitive murals and ceiling art. Perhaps modern rules prevented Resnais from enhancing his legendary scenes with clouds of smoke, or perhaps he did not want to impair his pristine imagery. Alcohol, however, is OK. Bartenders are just about the only visible hotel staff, though none of the guests really appears to be drinking.

Volker Schlöndorff, an assistant director on this film who would win an Oscar for his 1979 film “The Tin Drum,” states in DVD commentary that Resnais, a French New Wave figure aligned with the Left Bank, wanted a “very special black and white ... Of course the model was Antonioni’s films.” At the time “Marienbad” was filmed, late 1960, it was just before Antonioni was to deliver the works that elevated him to international stardom: “L’Eclisse,” “La Notte” and “L’Avventura.” About 12 minutes in to “Marienbad,” a man will appear slightly levitated in the corner of a scene in a nod to Hitchcock. Checkerboard designs are common. In a few climactic moments, Resnais will show Seyrig in an overexposed white frame resembling an image from the silent era.

Transitional point of view is another effect, not unlike the first-to-third person in “La Dolce Vita.” Fairly early, the camera will pass by “M” as he stands in front of a wall; as the camera goes through a doorway, “M” approaches from right to left on the other side of the wall. A similar depiction occurs when a couple walks out of a room past “X,” then he passes them on the other side.

For such a visual tour de force, “Marienbad” is dubiously reliant on dialogue. Imagine it without any. We would see “X” constantly approaching “A” with some story or recollection she declines to accept. We hear at one point that “Frank” might have taken a photo a year ago and later that “Frank” apparently was not present a year ago.

Without dialogue, we probably wouldn’t understand the rules of the table game, a variation of Nim. “M” asserts that he doesn’t lose, which goads others into challenging him. But the other players don’t have any strategy and believe they can win by simply guessing. Are there any consequences to this game? No, except as an avenue for defeating “M.”

Roger Ebert put “Marienbad” in his “Great Movie” ledger in 1999, after its DVD release. He recalls lining up to see it at age 19 and writes that he expected the later viewing to be a “cerebral” one. Instead, he was stunned by the “voluptuous quality” of the work. He draws a comparison to Kubrick, but unlike others who cite “The Shining,” he likens the mise-en-scène to the bedroom at the end of “2001.” Ebert suggests the meaning is about how “life presses on indifferently toward its own inscrutable ends.”

In a 1960s essay, Pauline Kael wrote that she “laughed” at the view of Seyrig’s “elegant backside” and took Seyrig’s “high-toned” walk for parody. Kael observed that Resnais (yes) and Robbe-Grillet (no) gave differing answers as to whether “X” and “A” really had met the year before. Both Kael and Ebert include the term “vampire” in their descriptions. Kael derided the film as “empty” — “lousy story, but great sets” — and compared it to “La Notte,” “La Dolce Vita” and “The Rules of the Game.”

“Marienbad’s” greatest honor is the Golden Lion. It received one Oscar nomination, not for the photography but to Robbe-Grillet for original screenplay, where he and Ingmar Bergman (“Through a Glass Darkly”) came up short against the authors of “Divorce Italian Style.”

Among the theories of “Last Year in Marienbad,” the most distressing is the notion that “A” is a rape victim. In a pivotal conversation through doorways, “X” narrates, “You were afraid even then. ... But I loved your fear that evening ... letting you struggle a bit. I loved you. I loved you. There was something in your eyes. You were alive.” They nearly kiss. Then he says, “It was probably not by force ... but only you know.” The ending implies that “X” may have succeeded through persistence.

Neither Ebert nor Kael nor the New York Times’ Bosley Crowther mention the theory of assault, that “A” might be repressing memory of a catastrophic event. Seyrig, who died in 1990 at 58, emerged as a prominent feminist at least a decade after “Marienbad.” European film scholar Ginette Vincendeau asserts in DVD commentary that a rape scenario did not occur to critics of the time.

In his 2008 interview with François Thomas, Renais explains, in remarks translated to English, “The idea of a rape didn’t interest me at all. It’s one of the changes I asked Robbe-Grillet to make to the screenplay. I asked his permission to not shoot anything like a rape scene. ... I didn’t feel it fit in this screenplay at all.

“For me, it’s a film about persuasion, conquest, an encounter. To me it was a simple love story,” he continued, stating he wanted to express the idea of love, “precisely the opposite” of the notion of rape.

“Marienbad” was produced at a time, and certainly depicts a time, when a woman was either “Miss” or “Mrs.” and male suitors were allowed to express certain liberties taboo today as tragic accounts of sexual harassment, exploitation, abuse and assault pile up. In “Marienbad,” there is a fighting chance that “A,” and not “M” or “X,” is in control of the situation.

Are “A” and/or “X” vulnerable? Yes, and this is the high drama. “X” is on the verge of massive heartbreak, realizing that the entire previous year has been in vain, that the staggering beauty he remembers and envisions didn’t happen or won’t happen. “A” might be re-encountering her prince who will save her from “M” ... or she might be running off with a con artist.

Many have felt they were holding the last matchstick after watching “Marienbad.” They shouldn’t underestimate the persistence of this timeless masterwork.

4 stars

(January 2019)

(Updated May 2022)

“Last Year at Marienbad” (1961)

Starring Delphine Seyrig

as A — la femme brune ♦

Giorgio Albertazzi

as X — l’homme à l’accent italien ♦

Sacha Pitoëff

as M — l’autre homme au visage maigre, le mari ♦

Françoise Bertin

as Un personnage de l’hôtel ♦

Luce Garcia-Ville

as Un personnage de l’hôtel ♦

Héléna Kornel

as Un personnage de l’hôtel ♦

Françoise Spira

as Un personnage de l’hôtel ♦

Karin Toche-Mittler ♦

Pierre Barbaud

as Un personnage de l’hôtel ♦

Wilhelm von Deek

as Un personnage de l’hôtel ♦

Jean Lanier

as Un personnage de l’hôtel ♦

Gérard Lorin

as Un personnage de l’hôtel ♦

Davide Montemuri

as Un personnage de l’hôtel ♦

Gilles Quéant

as Un personnage de l’hôtel ♦

Gabriel Werner

Directed by: Alain Resnais

Written by: Alain Robbe-Grillet

Producer: Pierre Courau

Producer: Anatole Dauman

Producer: Raymond Froment

Co-producer: Robert Dorfmann

Music: Francis Seyrig

Cinematography: Sacha Vierny

Editing: Jasmine Chasney, Henri Colpi

Production design: Jacques Saulnier

Set decoration: Jean-Jacques Fabre, Georges Glon, André Piltant

Costumes: Bernard Evein

Makeup and hair: Alexandre Marcus, Elyane Marcus

Post-production supervisor: Michel Choquet

Production manager: Léon Sanz

Script girl: Sylvette Baudrot