Pauline Kael on ‘Star Wars’ — plus the misfire on Obi-Wan & the afterlife

Alec Guinness is the lone actor receiving an Oscar nomination for the original “Star Wars.” Academy voters skew older, and Guinness was the most esteemed actor of the crew, so that kind of makes sense.

No, wait a minute — it doesn’t.

Guinness actually looked down upon the role, according to his authorized biography. “Fairy-tale rubbish but could be interesting perhaps,” he wrote to a friend. He took the job for the money — apparently $300,000 plus 2% of the producer’s profit, which reportedly brought him $7 million shortly after the film’s release and up to $95 million by the time of his death in 2000.

Yes, George Lucas overpaid. Someone else would’ve taken much less — particularly for 20 minutes of screen time. Pauline Kael did call Obi-Wan the “guru” of the film, which is not inaccurate. Yet in a production that is incredibly inspired on so many levels, the highly paid Alec Guinness character is little more than an usher for Luke Skywalker.

Perhaps “narrator” is a better term. “Star Wars” is Luke’s coming-of-age story. But the audience will realize it well before Luke does. The lad, despite living with an aunt and uncle, somehow knows virtually nothing about his own family nor the fact his parents were involved in epic battles for control of the galaxy. That will all gradually be explained by Obi-Wan — very gradually, because he has long anticipated that this day would come and believes that too much information may tempt the son the way it did the boy’s impulsive father in a gargantuan story that actually sounds more exciting than the adventure we’re embarking upon but is left questionably offscreen, saved for another movie a quarter-century later.

The volume of “Star Wars” did not impress Kael. “The loudness, the smash-and-grab editing, the relentless pacing drive every idea from your head,” is how Kael begins a September 1977 description of the film, which she apparently did not formally review earlier. “There’s no breather in the picture, no lyricism; the only attempt at beauty is in the double sunset. It’s enjoyable on its own terms, but it’s exhausting, too: like taking a pack of kids to the circus.”

The assessment by Kael, 58 at the time of writing, goes a long way toward explaining the extraordinary, perhaps still unmatched, age gap in “Star Wars” appreciation. For anyone not yet out of high school by 1977 and also some that were, “Star Wars” is the most fantastic movie experience that will ever exist. Those who recall the TV news clips of lines around the blocks at theaters, all those Halloween 1977 Jawa or sand people or stormtrooper costumes, and the movie returning — again and again to first-run theaters until 1980, when the sequel finally arrived — will never again see a film with this kind of presence.

“An hour into it, children say that they’re ready to see it all over again,” Kael laments, even though she determines that “Going a second time would be like trying to read Catch-22 twice.” (Whether she actually spoke with children an hour into the movie, or heard or saw comments from them afterward, is unknown.)

The Wikipedia page for the film says that at MPAA, “votes for the rating were evenly split between G and PG,” and that Fox argued for the latter, which it received, partly because it feared teenagers may regard a “G” as “uncool.”

The “Star Wars” phenomenon demonstrates the massive importance of simplicity — plots and directions that children can understand, not just in cinema but in ... anything. Is this film merely a “children’s movie” that hit it big? Numerous critics did praise it, but that doesn’t mean they “got” it. Critics heaped praise on “Sesame Street” too but weren’t making it must-see TV every day as 5-year-olds were.

Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel each has “Star Wars” on his Top 10 list for 1977, 7th for Siskel and 10th for Ebert. Siskel nevertheless complains of the “inanity of the entire enterprise” and says it “simply is a fun picture.” Vincent Canby calls it the “most beautiful movie serial ever made” and deems it “fun and funny” and “good enough to convince the most skeptical 8-year-old sci-fi buff” but cautions readers not to approach it as a “literary duty.”

Which is apparently what Kael was doing. Her assessment takes a blunt instrument to the age-old critical fault line — is the cinema a form of art, or entertainment? And must those concepts be separate, or qualified? “Even if you’ve been entertained” by “Star Wars,” Kael writes, “you may feel cheated of some dimension — a sense of wonder, perhaps.” But can’t a product of massive “entertainment” also be a masterwork?

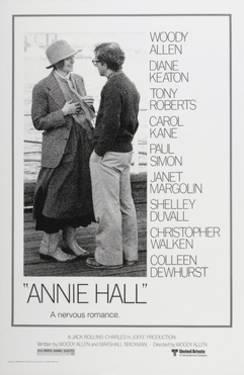

In Hollywood, pretty much nothing beats a moneymaker, except at the Oscars. “Star Wars” was nominated for 11 Academy Awards and actually won 6, many of them technical awards. But the artisans made a statement too. In one of the most debated outcomes, “Annie Hall” won best picture, best director, best actress and best orginal screenplay. Those triumphs, Siskel notes in his coverage, “clashed with a long-standing Academy tradition of not honoring comedies.”

Perhaps the commotion of “Star Wars” cited by Kael is the reason that Oscar voters were compelled to mark “Alec Guinness” on their ballots. “It’s a huge hit,” so something must have worked, and for enough Academy members, it was the quiet, beaten-down, fate-accepting Obi-Wan, perhaps embodying the way adults such as Kael felt about the cosmic chaos of the film. But what seems a gentle nod to a popular veteran is a disservice to the powerful work by the upstarts. It’s not Guinness but the charisma of Carrie Fisher and Harrison Ford that gives “Star Wars” its underrated character heft. They joust with each other far better than most rom-com couples, and each has a convincing argument. They are the characters of humor, a welcome contrast to Obi-Wan’s stoicism and Luke’s wide-eyed wonderment.

Kael misses this completely. The actors, collectively, “just seem to be bad actors ... their klunky enthusiasm polished at the Ricky Nelson school of acting,” Kael writes. She wasn’t alone, as Gene Siskel writes, “Save for Alec Guinness, the cast is unmemorable.”

Kael, though, did notice Fisher, a bit, as “the high-school-cheerleader princess-in-distress” who “talks tomboy tough” and in an unintentional foretelling of the sequel wonders if “it didn’t occur to anybody that she could get The Force?”

There are millions of things to be said (and that have been said) about “Star Wars.” If you set out to find every possible relevant observation about the film, you’d never finish. Blogs, books, newsletters, reviews, documentaries, interviews, conventions, reddit chats. It’s a movie/series that checks a large amount of boxes. One of those would be Connecting With The Deceased.

In many movies, characters draw inspiration from the dead. Sometimes, including the recent Paul Thomas Anderson masterwork “Phantom Thread,” characters envision images of deceased relatives/friends/mentors, and it might be left to the viewer to decide if the decedent is, in some way, present.

That the aging, declining Obi-Wan must pass away for his young protégé to fulfill his own destiny seems obvious or even routine; it even happens in “Road House.” The significant decision by George Lucas is what happens afterward — that Obi-Wan, deceased, will actively communicate with the living to guide the living to victory in a life-or-death struggle. This is a major determination and a lot rarer than you might think. Something like Patrick Swayze in “Ghost.”

Probably most movies look great on paper, and only when the cameras roll do the filmmakers really figure out what’s going on. Lucas presumably recruited Guinness so vigorously because he envisioned Obi-Wan as the Vito Corleone of his picture. On that scale, “Star Wars” starts much later than “The Godfather,” not with Obi-Wan in his prime but more like the rickety Brando at the mob meeting. Vito is able to hold a shaky truce, giving Mike time to prepare for an epic showdown. Obi-Wan is able to get Luke to the Princess, at which point Luke and the Princess can compare notes and defeat the enemy with their own emerging skill.

What most likely happened is that Lucas noticed his other supporting characters clicking — “This is coming together better than I thought” — and quickly lost interest in his unimpressed guru figure and even in the guru’s exit. How can he cleanly get him out of the picture? Lucas delivers a duel that ends in a dud. How should Obi-Wan die? Wipe out the bad guys and be mortally wounded? Get caught in a trap? Something that’s Luke’s fault? Natural causes, like Vito? The decision curiously is suicide, but maybe it’s not suicide, because of the caveat that it will somehow make Obi-Wan more powerful than he already is, a prophecy never fulfilled by this film or future ones. And if it was, then Vader should know that the lowering of the saber is a trap. Obi-Wan’s move is perhaps not far from Father Merrin’s demise in “The Exorcist,” in which he is able to damage the enemy and set up his allies for victory but expects that the ordeal may take his own life.

Obi-Wan’s final act is a tightrope walk to disable a tractor beam that will allow the group to escape the Death Star. But even after getting away, Leia will observe, “They let us go. It was the only reason for the ease of our escape.”

Rather than go out in a signature act of heroism, Obi-Wan’s fate seems more like a half-hearted write-off. But it only gets worse. Lucas makes the extraordinary decision that Obi-Wan (alone among characters) still lives in the afterlife (at current age) and can toggle back to reality. So we learn that this is an epic struggle worth fighting, but that the noble characters are not going to die anyway and will even become more powerful once “slain” by the enemy, in a separate world set off by a boundary.

Obi-Wan’s cinematic enemy is not actually the Dark Side. It’s the other supporting cast. Darth Vader is probably only the Greatest Movie Villain of all time. As for the gang of good guys, Roger Ebert thought they must’ve been based on “The Wizard of Oz”; Gene Siskel and Vincent Canby favorably likened C-3PO and R2-D2 to Laurel & Hardy, “the most enjoyable characters in the film.” The camera finds them, and keeps finding them, even in Guinness’ presence.

The notion of rescuing a woman is a Force of its own. Sometimes, “Star Wars” is compared to “The Searchers.” In that movie, and in certain others such as “The Godfather” or “Taxi Driver” or even the real-life Patty Hearst story, a woman does not want to be rescued. Leia does, even if she’s not so impressed by her rescuers. (Imagine if she told them, “Go away. I’m staying.”) But this is not a femme fatale; she is 100% bravery, and her immense courage will shame others into rallying for her cause. She is still highly vulnerable, and when she is the one bestowing awards at the ending, it feels like the ultimate male accomplishment, for at least one of these two fellows.

“Star Wars” is fantasy. Its deployment of Obi-Wan in the afterlife puts it in the realm of “Field of Dreams” and “Heaven Can Wait,” but this concept is not monolithic, there’s a wrinkle to each interpretation. “Field of Dreams” also involves deceased characters contacting living ones, but these deceased do not actually know the living people, there is a wall between the groups (at least until the end), and the partnership is not over some great struggle, but real estate. In “Heaven Can Wait,” a deceased character summons a living friend, not to help the living friend but so that the living friend can help the decedent, who hopes to regain something of his normal life.

You go all in, or not at all. Those other movies demonstrate that the afterlife can work wonderfully as a movie plot. As an afterthought, as it is in “Star Wars,” it’s an intrusive bust that detracts from the life-or-death drama. If anything, the rest of “Star Wars” is about relying on the people with you in the here and now.

Obi-Wan does not appear physically to Luke in Luke’s X-Wing attack on the Death Star, but his voice will exhort him to “Use the Force,” prompting Luke to shut down his radar and operate on instinct. Lucas clearly does not deem this a particularly powerful moment, because it’s not Obi-Wan who knocks Vader off the chase, it will be Luke’s pal Han Solo who has gloriously rejoined the battle at just the right time.

Sometimes, actors have tortured relationships with well-known roles. This is one of those times. For a job he disdained, Guinness collected tens of millions of dollars and an Oscar nomination. He didn’t want to do the sequel either and wrote, “It’s dull rubbishy stuff but, seeing what I owe to George Lucas, I finally hadn’t had the heart to refuse.” The things that money can do to people.

4 stars

(April 2024)

“Star Wars” (1977)

Starring

Mark Hamill

as Luke Skywalker

♦

Harrison Ford

as Han Solo

♦

Carrie Fisher

as Princess Leia Organa

♦

Peter Cushing

as Grand Moff Tarkin

♦

Alec Guinness

as Ben Obi-Wan Kenobi

♦

Anthony Daniels

as C-3PO

♦

Kenny Baker

as R2-D2

♦

Peter Mayhew

as Chewbacca

♦

David Prowse

as Darth Vader

♦

Phil Brown

as Uncle Owen

♦

Shelagh Fraser

as Aunt Beru

♦

Jack Purvis

as Chief Jawa

♦

Alex McCrindle

as General Dodonna

♦

Eddie Byrne

as General Willard

♦

Drewe Hemley

as Red Leader

♦

Dennis Lawson

as Red Two (Wedge)

♦

Garrick Hagon

as Red Three (Biggs)

♦

Jack Klaff

as Red Four (John D.)

♦

William Hootkins

as Red Six (Porkins)

♦

Angus Mcinnis

as Gold Leader

♦

Jeremy Sinden

as Gold Two

♦

Graham Ashley

as Gold Five

♦

Don Henderson

as General Taggi

♦

Richard LeParmentier

as General Motti

♦

Leslie Schofield

as Commander #1

Directed by: George Lucas

Written by: George Lucas

Producer: Gary Kurtz

Executive producer: George Lucas

Music: John Williams

Cinematography: Gilbert Taylor

Editor: Richard Chew, Paul Hirsch, Marcia Lucas

Casting: Diane Crittenden, Irene Lamb, Vic Ramos

Production design: John Barry

Art direction: Leslie Dilley, Norman Reynolds

Set decoration: Roger Christian

Costumes: John Mollo

Makeup and hair: Stuart Freeborn, Rick Baker, Doug Beswick

Production manager: Bruce Sharman

Production supervisor: Robert Watts

Production manager: second unit: Peter Herald

Production manager: second unit: Pepi Lenzi

Production manager: second unit: David Lester

Stunts: Peter Diamond