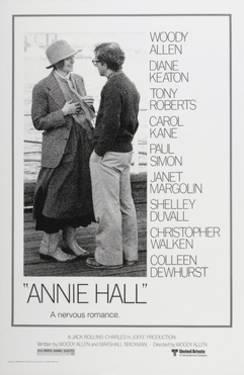

Wit to be tie’d — ‘Annie Hall’ is about a comedian who’s no fun to be around

An important scene occurs at the 10-minute mark of “Annie Hall.” Alvy and Annie find themselves in a movie line in front of a windbag who is complaining about the “indulgent” tendencies of Federico Fellini.

Why is Alvy so irritated by this gentleman? Is the man wrong about Fellini? It would seem the type of discussion Alvy would enjoy. But Alvy expresses no opinion on Fellini. A couple of times, he tells Annie the man is loud. Once, he says the man is spitting on his neck.

All we really know is that Alvy is touchy and that his afternoon is not going well. What sets up potentially as a comedic grand slam of the Harvard bar scene in “Good Will Hunting” ends with a thud, after three minutes, when Marshall McLuhan steps out behind a sign reciting his lines as if they’re on cue cards, offering the Fellini critic this curious assessment: “You mean my whole fallacy is wrong.”

The Fellini critic is possibly not talking about Fellini, but Woody Allen. That would’ve made for a much better joke and would be within the extraordinary artistic license of the film in which Allen, as Alvy, occasionally interrupts a scene to narrate and recap.

Instead, the three minutes in the line for “The Sorrow and the Pity” is “Annie Hall” in brief: scattershot, tedious, meandering, underachieving comedy with tiny inserts of filmmaking brilliance.

It’s at the 25th minute that we see Annie in the outfit that will somehow catapult this movie to Hollywood immortality. The costume designer, Ruth Morley, catches lightning, puts Diane Keaton in a necktie and baggy pants, for about eight minutes, and suddenly, we have a legend. Somehow, though the film won best picture and received five Academy Award nominations, Morley was not among them. Best costume design went to John Mollo of “Star Wars.” The nominees included the venerable Edith Head (for “Airport ’77”), Anthea Sylbert for “Julia,” Florence Klotz for “A Little Night Music” and Irene Sharaff for “The Other Side of Midnight.”

The “Annie” moment is presumably a clumsy flashback to when Annie and Alvy first meet, at a co-ed tennis match with mutual friends. Perhaps both are comfortable with each other at the tennis club for the same reason many couples initially click — there is no expectation that they should. Or perhaps Alvy just likes her clothes.

By the end of the film, there is no meaning to their relationship, no reason for them to be together, and no reason to care that they aren’t.

Pauline Kael disagrees. Kael apparently didn’t review “Annie Hall” but in her review of Keaton’s “Looking for Mr. Goodbar,” Kael writes that audiences saw it as, “Even if it was, finally, somewhat disappointing, it was still about living now — even the falling apart of the “relationship” was appealing.

“Annie Hall” rains jokes, and the comedy quickly gets watered down. The biggest joke is the one on Annie. She's not a girlfriend but a magician’s assistant, a receptacle for Allen’s formidable punch lines. But there are too many, and the best ones are early, and (save for a scene involving cocaine), the comedy is all verbal, never physical. The movie could conceivably play on a satellite radio channel, no images, the gags being enough, but there are so many of them, it is as if Vermeer started churning out one painting a day later in his career, diluting the gems. We are supposed to see two people constructing and deconstructing a relationship. They just share scenes.

It’s Allen’s film, but its endurance seems to be the appeal of Keaton, not just to males. She is portrayed as lacking Alvy’s brainpower but nevertheless is a dream date for the intellectually minded man. Beautiful, down to earth, charming, sexually liberal, experimental, breezy, happy, singing, comfortable with elites, you can proudly introduce her to Marshall McLuhan. She’s also the friend every woman likes to have, beautiful/modest/non-judgmental/non-threatening. What she’s not is funny. He’s a comedian. She isn’t. “Annie Hall” inadvertently illustrates an important distinction in films and TV — the difference between having a sense of humor and actually being funny.

The Hollywood Reporter reviewer in 1977 says the film is “irresistible” but “especially if you find Keaton as well-nigh irresistible as I do.” He could replace “especially” with “only” and be right on target.

Roger Ebert wasn’t as hooked, waiting until the 620th word of his review to even mention Keaton’s name. He offered 3½ stars for the film in 1977, then upgraded it to four decades later.

What of the male lead? Allen was nominated for the best actor Oscar but lost to Richard Dreyfuss of “The Goodbye Girl,” a story of another male having ups and downs sharing a New York apartment with a woman. Allen’s frustrations though draw far more parallels with Albert Brooks’ exasperation a decade later in “Broadcast News.” Cinematically, Allen is a character actor but a writer of such skill that he can’t resist, like Orson Welles, casting himself as a lead. Well, that’s their prerogative.

It’s well-known that Allen’s favorite director is Ingmar Bergman, the figurehead of the auteur class nearly as famous for what they developed offscreen: the concept of the cinematic “muse,” the mesmerizing young actress who connects with the already celebrated auteur in such a way as to take his vaunted work to another level. For Bergman, it was Harriet Andersson (who isn’t really regarded as a muse), Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullman; Godard had Anna Karina, Antonioni had Vitti, Rossellini emerged with the other Bergman. There were “prepackaged” couplings too; Fellini and Masina and Cassevetes & Rowlands.

It’s entirely possible that this and not the Oscars is the favorite scorecard of auteurs, A) did he land the most intriguing actress B) not just for his film but his personal life and C) are she/he good enough to qualify her as his “muse”?

In his original review of “Annie Hall,” the New York Times’ Vincent Canby stated “Miss Keaton emerges as Woody Allen’s Liv Ullman,” though that implies he already had a Harriet Andersson and Bibi Andersson, which he really didn’t, unless you want to count Louise Lasser, whose notoriety stems from her post-Allen work in “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman.”

Keaton and Allen had a relationship in the early 1970s since she starred in the Broadway version of “Play It Again, Sam,” and though the relationship ended shortly after, the two remained artistic collaborators through the ’70s. “Annie Hall” undoubtedly draws upon some of their intimate moments together. Keaton’s actual surname is Hall, and she apparently was called Annie. Annie is just the most attractive member of the supporting cast that exists to provoke Alvy, whenever Alvy stops talking, which isn’t often. Dubious-looking passersby are summoned for the types of jokes Annie can’t deliver. When the supporting cast runs dry, there’s another reference to undergoing analysis, or Woody turns to the camera, perhaps to repeat for the second or third time the old Groucho Marx joke about not wanting to join a club that would have him as a member. Bergman may be his idol, but Allen demonstrates a Godard-like awareness here that the fourth wall is breakable.

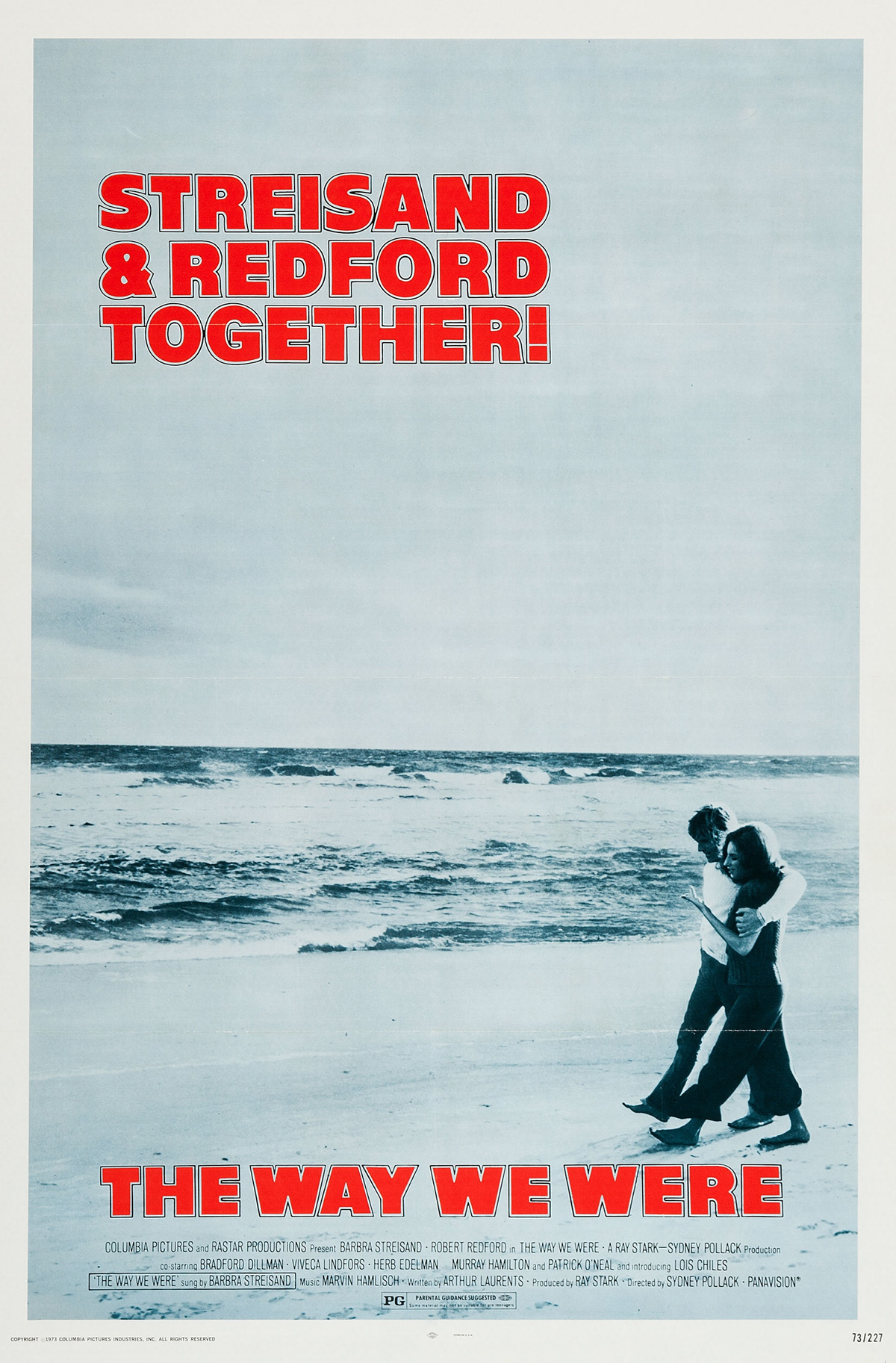

As much as Allen channels Bergman in this film, he might also be invoking “The Way We Were.” A Jew and gentile among the bourgeoisie give us ups and downs in New York, and then things unravel in Hollywood. They had no business being together, and by the end of the film, they realize it. The point of “The Way We Were” is to put two megastars in bed together; the point of “Annie Hall” is an elongated stand-up routine.

“The Way We Were” was regarded by critics as highly flawed. It’s curious then that the nearly equally dysfunctional “Annie Hall” cleaned up at the Oscars and ranked 31st in the inaugural (1998) AFI list of the 100 greatest American movies. “The Way We Were” had the song. “Annie Hall” had Keaton’s tie.

It was said by “The Way We Were” insiders that Robert Redford took the role only reluctantly, assuming correctly the film would be Streisand’s vehicle. One wonders if Keaton felt the same about “Annie Hall.” Annie proves no more significant than the dozen other characters Alvy crosses paths with.

Regardless, the appreciation for Keaton, who collected the best actress Oscar in her only win, is enough that “Annie Hall” is wrongly but widely deemed a “romance” when there is none. Without Annie, Alvy just moves on to his next date. In perhaps unintentional irony, the second scene of the lobsters on the floor proves it really doesn’t matter who else is in the frame.

Roger Ebert in his original 1977 review says the film is called a “nervous romance.” Gary Arnold in 1977 in The Washington Post states the film has the “makings” of a romantic comedy. Richard Roeper uses the term “romantic comedy” but asserts the film is a “bittersweet slice of life.”

There’s a reason comedies typically run less than the standard two-hour movie time and typically check in at 90 minutes, as does “Annie Hall.” It’s hard to make people laugh for even 60 minutes. Allen does that, then the material runs dry down the home stretch, reliant on New York put-downs of Southern California. Speaking of which, the uninspired photography makes one of the film’s heroes — New York City — appear indistinguishable from, say, Milwaukee.

That’s a major disappointment, because there is filmmaking greatness here. Allen’s specialty is writing gags. In this film, he wows with deviously clever cinematic devices of Keaton talking out of body, of subtitles explaining what characters are really thinking, of Alvy inserted into the “Snow White” wicked queen cartoon, of the McLuhan presence. Other scenes seem amateurish. From a strange and too-repetitive car angle, we learn Annie is a bad driver. The amount and arrangement of flashbacks, in a 91-minute film, are clumsy and hardly Tarantino-esque. Like a typical standup routine, one can tune in to “Annie Hall” at any scene for a few laughs regardless of what’s come before or is coming after.

Allen never conveys why Alvy and Annie need to be together. Annie does have a family but apparently no friends. You’ll be wondering well into the film what she does for a living. It is significant that Alvy says in the opening scene, “Annie and I broke up. And uh, I still can’t get my mind around that. ... Where did the screw-up come?” That this is delivered in a comic monologue and includes the term “screw-up” is emotional clearance, we know how it will end, and we’re in for comedy here, not heartbreak.

“Hall” zinged Hollywood, but Hollywood smiled on “Hall.” Its Oscar nominations were the first of Allen’s already impressive career. The film won best picture and four of its five Oscar nominations, including Allen for directing and original screenplay. Roger Ebert wrote in his 1977 review that “the movie represents a growth on Allen’s part.” That was obviously consensus. Afterwards, the Academy couldn’t cut him off; he has 19 career nominations.

“Annie Hall” is half of one of the most famous best-picture showdowns. It beat George Lucas’ megahit “Star Wars” (and three others), an outcome Ebert concluded in 2002 would be “unthinkable today.” But while “Star Wars” owned the pre-college crowd, “Annie Hall” and the rest of Allen’s canon is red meat for the intellectually curious, middle-aged urban sophisticates notoriously underserved by Hollywood. They appear to want to like the film more than they actually should.

How “Hall” became their champion, and as Richard Roeper put it, Allen’s “signature film” and “certainly most popular,” is probably owing to Keaton’s wardrobe. Frankly, some best picture winners simply aren’t that good. Every year, someone has to win. Almost anyone gets Allen’s comedy. It’s whether they get Keaton that matters.

2 stars

(April 2018)

“Annie Hall” (1977)

Starring

Woody Allen as

Alvy Singer ♦ Diane Keaton as

Annie Hall ♦ Tony Roberts as

Rob ♦ Carol Kane as

Allison ♦ Paul Simon as

Tony Lacey ♦ Shelley Duvall as

Pam ♦ Janet Margolin as

Robin ♦ Colleen Dewhurst as

Mom Hall ♦ Christopher Wlaken as

Duane Hall ♦

Donald Symington as

Dad Hall ♦

Helen Ludlam as

Grammy Hall ♦

Mordecai Lawner as

Alvy’s Dad ♦

Joan Newman as

Alvy’s Mom ♦

Jonathan Munk as

Alvy - Age 9 ♦

Ruth Volner as

Alvy’s Aunt ♦ Martin Rosenblatt as

Alvy’s Uncle ♦

Hy Ansel as

Joey Nichols ♦

Rashel Novikoff as

Aunt Tessie ♦

Russell Horton as

Man in Theatre Line ♦

Marshall McLuhan as

Marshall McLuhan ♦

Christine Jones as

Dorrie ♦ Mary Boylan as

Miss Reed ♦ Wendy Girard as

Janet ♦ John Doumanian as

Coke Fiend ♦

Bob Maroff as

Man #1 Outside Theatre ♦ Rick Petrucelli as

Man #2 Outside Theatre ♦

Lee Callahan as

Ticket Seller at Theatre ♦ Chris Gampel as

Doctor ♦ Dick Cavett as

Dick Cavett ♦

Mark Lenard as

Navy Officer ♦

Dan Ruskin as

Comedian at Rally ♦

John Glover as

Actor Boy Friend ♦

Bernie Styles as

Comic’s Agent ♦

Johnny Haymer as

Comic ♦

Ved Bandhu as

Maharishi ♦

John Dennis Johnston as

L.A. Policeman ♦

Lauri Bird as

Tony Lacey’s Girlfriend ♦

Jim McKrell as

Lacey Party Guest ♦

Jeff Goldblum as

Lacey Party Guest ♦

William Callaway as

Lacey Party Guest ♦

Roger Newman as

Lacey Party Guest ♦

Alan Landers as

Lacey Party Guest ♦

Jean Sarah Frost as

Lacey Party Guest ♦

Vince O’Brien as

Hotel Doctor ♦

Humphrey Davis as

Alvy’s Psychiatrist ♦

Veronica Radburn as

Annie’s Psychiatrist ♦

Robin Mary Paris as

Actress in Rehearsal ♦

Charles Levin as

Actor in Rehearsal ♦ Wayne Carson as

Rehearsal Stage Manager ♦

Michael Karm as

Rehearsal Director ♦

Petronia Johnson as

Tony’s Date at Nightclub ♦

Shaun Casey as

Tony’s Date at Nightclub ♦

Ricardo Bertoni as

Waiter #1 at Nightclub ♦

Michael Aronin as

Waiter #2 at Nightclub ♦

Lou Picetti as

Street Stranger ♦

Loretta Tupper as

Street Stranger ♦

James Burge as

Street Stranger ♦

Shelly Hack as

Street Stranger ♦

Albert Ottenheimer as

Street Stranger ♦

Paula Trueman as

Street Stranger ♦

Beverly D’Angelo as

Actress in Rob’s T.V. Show ♦

Tracey Walter as

Actor in Rob’s T.V. Show ♦

David Wier as

Alvy’s Classmate ♦

Keith Dentice as

Alvy’s Classmate ♦

Susan Mellinger as

Alvy’s Classmate ♦

Hamit Perezic as

Alvy’s Classmate ♦

James Balter as

Alvy’s Classmate ♦

Eric Gould as

Alvy’s Classmate ♦

Amy Levitan as

Alvy’s Classmate ♦

Gary Allen as

School Teacher ♦

Frank Vohs as

School Teacher ♦

Sybil Bowan as

School Teacher ♦

Margaretta Warwick as

School Teacher ♦

Lucy Lee Flippen as

Waitress at Health Food Restaurant ♦

Gary Muledeer as

Man at Health Food Restaurant ♦ Sigourney Weaver as

Alvy’s Date Outside Theatre ♦

Walter Bernstein as

Annie’s Date Outside Theatre

Directed by: Woody Allen

Written by: Woody Allen

Written by: Marshall Brickman

Producer: Charles H. Joffe

Associate producer: Fred T. Gallo

Executive producer: Robert Greenhut

Edited by: Ralph Rosenblum, A.C.E.

Art director: Mel Bourne

Costume designer: Ruth Morley

Director of photography: Gordon Willis, A.S.C.

Makeup and hair: Fern Buchner, Romaine Green, John Inzerella, Vivienne Walker

Editing: Wendy Greene Bricmont

Casting: Juliet Taylor/MDA