The Yoko-like drama in ‘Phantom’ is no thread-scratcher

It’s rare to watch an R-rated movie and not see a gun.

In “Phantom Thread,” barbs are the bullets. Deflecting them requires significant old money or significant chutzpah. The astonishing drama emerging from these testy conversations is a triumph of writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson, who has packaged this tinderbox into perhaps The Most Elegant Film Ever Made.

It is also, perhaps, The Last Film Ever Made by Daniel Day-Lewis, who disappointingly announced at age 60, months before the 2017 release of “Phantom Thread,” that he will “no longer be working as an actor.” He has yet to break that vow. Assuming he doesn’t, he went out on top.

Those seeing “Phantom” for the first time might find it ... unsatisfying. “All these people do is sit in a house all day and get cranky with each other and take measurements. It looks beautiful, but ...”

Fair enough. It’ll come. Indeed, “Phantom Thread” is not as perfect as some of Reynolds Woodcock’s creations. There are backstory crutches. There are doors literally closing when someone is being frozen out. There are people telling each other things for the benefit of the audience that they wouldn’t have to tell each other in real life. (“Barbara Rose pays for this house” would be one of them.)

And there may just not be enough vulnerability. We must be told exactly what is at risk by Reynolds’ snobby behavior; death or jail are not among the possible repercussions. Heartbreak? That is Anderson’s intent. Perhaps Reynolds Woodcock is a Gordon Gekko throwback; whatever his faults, we just like seeing him operate and don’t much care whether he comes out ahead in the end.

What Anderson and Day-Lewis and the co-stars, Lesley Manville and Vicky Krieps, accomplish is extraordinarily cliff-hanging breakfast table drama. Every line, every insult, every suggestion, every irritation feels real. A few retorts are predictable. Most are unexpected. He will not accept confrontation or interruption, though by declaring as much, he is only making the situation worse. “Phantom Thread” curiously takes to heart a punch line from “The Electric Horseman” — Breakfast really is the most important meal of the day.

Shortly into “Phantom Thread,” we learn about the unique 3-legged stool that is the foundation for the House of Woodcock. Reynolds is the artisan, the rainmaker, the breadwinner. His sister Cyril is the manager, the John Wooden to the Bill Walton. Interestingly, Jack Lemmon’s dress company in “Save the Tiger” is, circa 1973, run by a male, its right-hand man is a male, its top designer is a male and so is its legendary pattern cutter. The women in “Tiger” are wives, secretaries, models, prostitutes and hippies. Here in “Phantom,” a 2017 movie about a time 20 years prior to “Tiger,” there is a little diversity in the ranks — we have a woman co- in charge, with far more clout than Phil in “Tiger.”

Alma is the muse, the model who inspires the artist and thus is afforded a seat at the breakfast table. The muse, we learn very early, is expendable. In a first viewing, on the surface, Cyril may seem expendable too. Is she riding coattails? Here is what we can infer: Cyril is more entrenched in high society than Reynolds is. She is the top sales person. She orders the fabric. She pays the bills. She pays the taxes. (Always an issue for the self-employed.) She hires staff. She meets tight deadlines. She handles the apologies for Reynolds’ social offenses. She protects him like a bouncer. Her skills would be welcomed by many other elites. Without her, Reynolds would make stunning dresses, but he’d do it for one fashion house after another, bouncing around after wearing out his welcomes.

That is a setting. A good one. What’s the story? A coming-of-age tale at age 60? An extremely talented person does not seem to be enjoying life the way he should be. The argument, well shown, is that surrendering to life’s diversions could dull this person’s extraordinary talent. Is there some way he can enjoy the fruits of the immense status he has achieved while not losing his edge? Yes. To make it work, he does have to temporarily lose his edge. This is maybe the one predictability that Anderson concedes. After an hour of seeing Reynolds deliver one dressmaking conquest after another, we sense there has to be a fail coming. Maybe he gets cocky. Or lazy. Or distracted. His reputation is suddenly at risk.

There’s a great line in “Good Will Hunting” that should be more famous than it is: “It’s only about just a handful of people in the world who can tell the difference between you and me. But I’m one of ’em.” Imagine being shown five dresses, one by a world-renowned designer and four by art-school students. Would you guess which one is the designer’s? How do we know that Reynolds’ designs are good? Perhaps it’s obvious. Or perhaps that’s the realm of female viewers. Directors are intrigued by fashion shows. Many, such as that Isaac Mizrahi presentation in “For Love or Money,” seem determined to provide as much comedy as beauty. Anderson includes a showing in “Phantom Thread.” By some of the reactions, it is implied the show is successful, though we see that collecting himself through the stress of the show is difficult for the perfectionist Reynolds. In general, Anderson relies on the decorum at the house, and the VIP treatment of a couple select clients, to confirm Reynolds’ stature.

Most people are intrigued by feedback. One would have to think part of Reynolds’ mornings would involve reading the society pages in search of editorial content about his work — and pictures of the works of others. There’s an interesting line in “Save the Tiger: “Everybody copies.” Reynolds appears to be making what would be called timeless creations. But fashion is fickle. At times, such as when he and Cyril disagree with Alma on whether a certain fabric is correct for a certain dress, Reynolds demonstrates hubris. “Cyril is always right,” he says, though, “it’s right because it’s right.”

But a crucial scene in “Phantom Thread” may leave audiences indecisive. Reynolds is falling ill while assessing his own work, a wedding dress for a princess, and deems it “not very good,” even “ugly.” Is it really ugly? Presumably, no. They rush to rebuild it after he damages it, so it must be deemed OK by the “always right” Cyril and the trusty dressmakers and recipient. But is it OK? It seems the movie is demonstrating not that Reynolds has lost his touch, only his confidence.

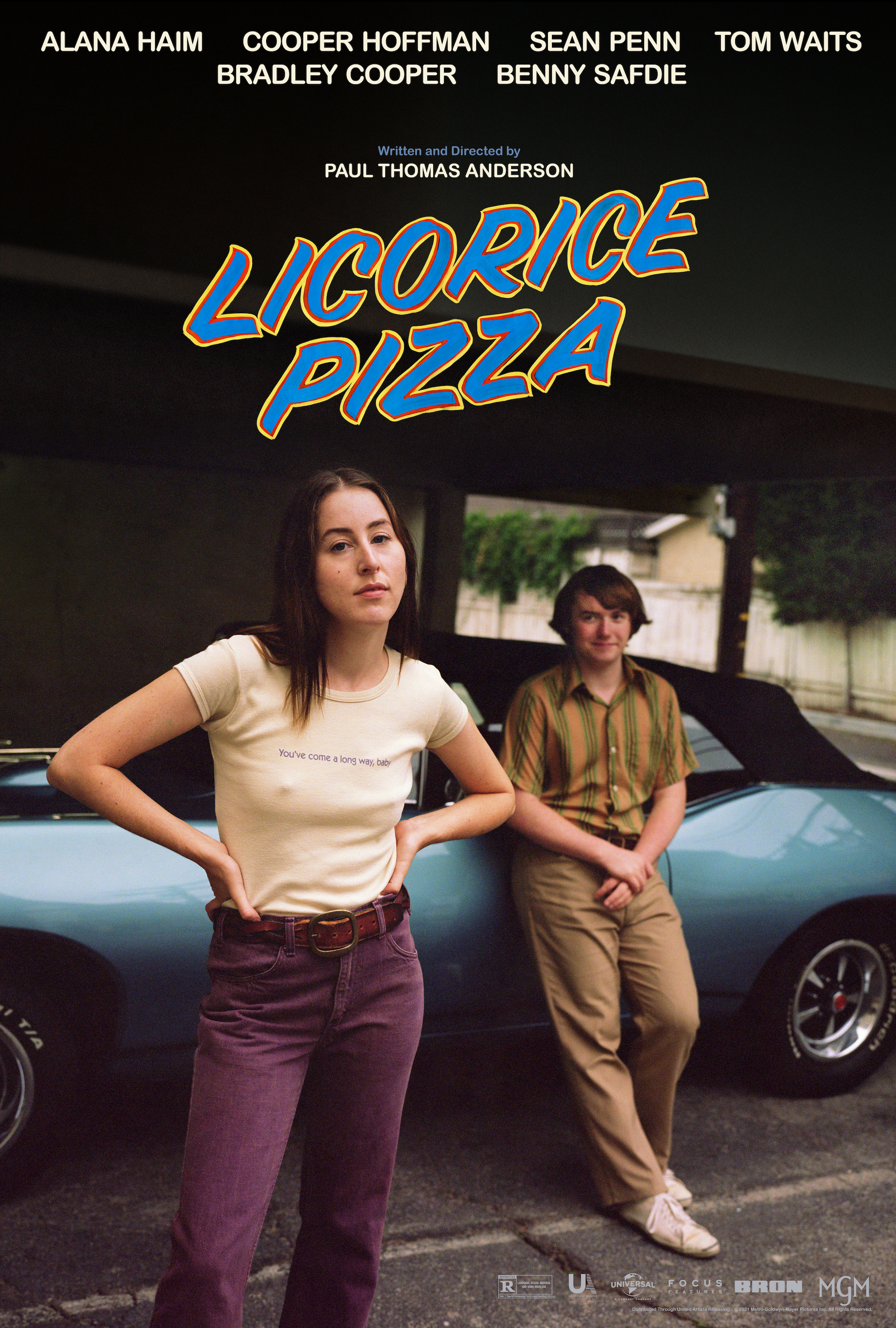

Anderson is the uncredited cinematographer of “Phantom Thread.” The lighting often resembles that in his subsequent movie, “Licorice Pizza.” Window light illuminates the House of Woodcock with an almost heavenly glow, to the point some scenes, including in other locations, appear to have a haze. Anderson seamlessly blends natural light, candles, chandeliers and fireplaces. His nighttime scenes are cozy, including the fireside conversation that establishes the movie’s (likely unnecessary and unmoving) flashback structure. Much like “Licorice Pizza” and “Boogie Nights,” the daytimes of “Phantom Thread” suggest boundless optimism; at night, the reckoning.

While eyes may focus on the dresses, take note of the attire worn by Woodcock staff. The dressmakers often resemble nurses. Or physicists. This is a dual assignment: Performing to the designer’s precise specs and handling his outbursts.

Surely, there must be numerous reviews and articles comparing Reynolds Woodcock to Warren Beatty’s George Roundy of “Shampoo.” But Google search indicates none. Like George, Reynolds has no sexuality hangups and thrives on his unique place in a typically woman’s world and apparently takes full advantage of being surrounded by beautiful women. “Phantom Thread” floated the concept of “toxic masculinity” years before “The Power of the Dog” cemented the term. That Reynolds Woodcock is a dressmaker is delicious irony on Anderson’s part. He could be a painter, a violinist, a physicist. He makes dresses and speaks about his career no differently than Ray Kinsella in “Field of Dreams.”

But unlike in “Shampoo,” Reynolds is not interested in seducing his clients. Note that each one, despite being of equivalent social class, doesn’t seem like a match: Too old, too young, too plain, too wacky. Instead, Reynolds hits on waitresses. George Roundy would likely call him an underachiever.

“Phantom Thread” is probably set in the 1950s because of the nostalgia it allows Anderson. This is the peak of high society, before Vietnam and the Swingin’ ’60s, when “chic” was a new thing and elites never dressed in T-shirts at the kinds of restaurants Reynolds frequents. When independent fashion houses could thrive without factories in Asia. But “Phantom Thread” may also be set in the ’50s to make another point — that business, even dressmaking, was a man’s world.

It doesn’t need to be set in the ’50s for another point — that male elites tend to wind up with much younger women. Vicky Krieps, the least famous of the three stars, is 26 years younger than Daniel Day-Lewis. Alma’s predecessor at the breakfast table, Johanna, is played by Camilla Rutherford, 19 years younger than Day-Lewis. Does he need a muse for business purposes, or is she simply for pleasure? If the former, it’s worth noting that Reynolds appears to do more designs for older women than younger women; is there some reason a 50-something woman couldn’t inspire him as much as a 30-something?

Krieps perhaps could’ve studied Yoko Ono. It is doubtful any of Reynolds’ customers, associates or fans want this person in his life. Anderson does not speculate as to whether she makes Reynolds’ product better. It seems he will eventually determine, after numerous ups and downs, that she makes his life better. At the ending, Alma will not be the film’s most popular figure.

The removal of the dress from Barbara Rose, perhaps the film’s most startling and powerful and effective scene, is equivalent to Patrizia investigating the knockoffs in “House of Gucci.” We have a lower-class outsider invited in to the family and, more or less, pronouncing its standards too low. Whether she actually believes this or is trying to outclass them is subject to opinion. Anderson beautifully sets this up. Alma cannot retrieve the dress alone. She needs Reynolds to issue the order. He can’t remove it himself because that would be a serious social if not legal breach. Both appear at Rose’s door, and the personal assistant who answers finds herself unable to prevent this two-layer intrusion and, impressively on Anderson’s part, seems indecisive as to whether it should happen. She ends up complying with this humiliation of her boss.

The completed repair of the Princess’ wedding gown marks the repair of Reynolds. While the finished dress sits in the room at sunrise, at the left, anchoring the frame, Reynolds comes downstairs, wakes up Alma and says, “I love you Alma. I don’t ever want to be without you.” She says, “I love you.” But there remains unfinished business, indicated by the clumsy exchange as he asks her to marry him. He wins the brief standoff here. “Yes,” she says, before adding, “Will you marry me?”

Like “The Devil Wears Prada,” we learn in “Phantom Thread” that the fashion world and high society are often more beastly than beauty. The public sees elites in stunning attire, not the backstabbing, sucking up, money-grubbing, gossiping, cursing, debauchery, drinking and discarding that unfortunately go with it. But “Phantom Thread” doesn’t fail the craft or its aspirations. It is a smashing triumph of capitalism. There is a firm belief among all parties that Reynolds’ work is worth it, that his talent is a gift to society, that those who can afford it should wear it, that spending large amounts of money on an article of clothing is an acceptable if not desirable pastime. The Princess owns the wedding dress, but all of society benefits by her wearing it, “Phantom Thread” says.

All of filmdom benefits from the work of Daniel Day-Lewis. “Phantom Thread” earned him his sixth Oscar nomination, all for lead actor roles. He lost to Gary Oldman of “Darkest Hour.” Among the regrets of “Phantom” is that there simply isn’t more commentary from Reynolds Woodcock on fashion, life, London, anything. He does not seem any more vigorous than a typical high-achieving 60-year-old, until he charges through the crowd at the New Year’s Eve ball and is briefly reminiscent of Day-Lewis’ characters in “Gangs of New York” or “There Will Be Blood.”

In a Hitchcockian manner, “Phantom Thread,” like “Boogie Nights” and “Licorice Pizza,” depicts males with curious relationships with their mothers. In “Licorice Pizza,” Gary boasts early that his mother “works for me,” and it sort of appears to be true. She’s a sign of his precociousness, that he has long been the breadwinner and she is little more to him than a typical employee. A key coming-of-age moment occurs when Gary’s mother is unable to take him to New York, and yet he’s able to find someone who can.

In “Boogie Nights,” Eddie’s combative disapproval from his mother sends him fleeing to an alternate family. In “Phantom Thread,” Reynolds longs for his mother as perhaps the only person he ever connected with. Early on, he reveals to Cyril that he has recently had the “strongest sense” that their mother is “near us.” This is a spoken crutch (later, a neatly visual one) supplying a reason as to why Reynolds might be on the verge of changing his ways with women, changing his life. He asks Alma about her mother but, like most people, prefers to talk about his own, imploring Alma, “Always carry her with you,” explaining his mother taught him his trade. But what a fascinating teaser by Anderson. What kind of conversations must they have had circa 1910, a mother realizing her boy wants to make dresses. Presumably, she recognized he was gifted and did not care what that might say about his sexuality. But maybe it was not that simple. Maybe she resisted. Maybe she lamented his career choice.

Cyril’s story leaves far more to the imagination. The name Cyril, according to Wikipedia, is masculine. Cyril of “Phantom Thread” is attractive, intelligent, savvy. And austere. Does she ever get asked out on dates? How come her brother, and not herself, is the family dressmaker? Did their mother advise her at a young age to guide her brother’s career? Did their mother favor boys? “Phantom Thread” may be illustrating old-world bias — Cyril and Reynolds are from a time when a man fronted the business, whatever the product, and the woman, however talented, was the support staff. Maybe we are seeing a person restrained by society. Is it possible Cyril is a superior designer to Reynolds? Thank you, PTA, for making us wonder.

4 stars

(September 2022)

“Phantom Thread” (2017)

Starring

Daniel Day-Lewis

as Reynolds Woodcock ♦

Vicky Krieps

as Alma ♦

Lesley Manville

as Cyril ♦

Julie Vollono

as London Housekeeper ♦

Sue Clark

as Biddy ♦

Joan Brown

as Nana ♦

Harriet Leitch

as Pippa ♦

Dinah Nicholson

as Elsa ♦

Julie Duck

as Irma ♦

Maryanne Frost

as Winn ♦

Elli Banks

as Elli ♦

Amy Cunningham

as Mabel ♦

Amber Brabant

as Amber ♦

Geneva Corlett

as Geneva ♦

Juliet Glaves

as Florist ♦

Camilla Rutherford

as Johanna ♦

Gina McKee

as Countess Henrietta Harding ♦

Philip Franks

as Peter Martin ♦

Tony Hansford

as Petrol Station Owner ♦

Steven F. Thompson

as Maitre’D ♦

George Glasgow

as Nigel Cheddar-Goode ♦

Niki Angus-Campbell

as Young Fan ♦

Georgia Kemball

as Young Fan’s Friend ♦

Nick Ashley

as Charles Gayford ♦

Ingrid Sophie Schram

as House Model ♦

Ellie Blackwell

as House Model ♦

Zarene Dallas

as House Model ♦

Brian Gleeson

as Dr. Robert Hardy ♦

Pauline Moriarty

as Minetta ♦

Harriet Sansom Harris

as Barbara Rose ♦

Eric Sigmundsson

as Cal Rose ♦

Phyllis McMahon

as Tippy ♦

Richard Graham

as George Riley, News of the World ♦

Silas Carson

as Rubio Gurrerro ♦

Martin Dew

as John Evans, Daily Mail ♦

James Thomson

as Reporter ♦

Tim Ahern

as Barbara’s Lawyer ♦

Lujza Richter

as Princess Mona Braganza ♦

Leopoldine Hugo

as Princess Mona’s Mother ♦

Delia Remy

as Bridesmaid ♦

Alice Grenier

as Bridesmaid ♦

Emma Clandon

as Reynolds’ Mother ♦

Ian Harrod

as Registrar ♦

Sarah Lamesch

as Steff ♦

Julia Davis

as Lady Baltimore ♦

Sir Nicholas Mander

as Lord Baltimore ♦

Jordon Stevens

as Lady Baltimore’s Daughter ♦

Michael Stevenson

as MC, New Year’s Eve Party ♦

Jane Perry

as Mrs. Vaughan ♦

Charlotte Melen

as Young Fashionable Woman

Directed by: Paul Thomas Anderson

Written by: Paul Thomas Anderson

Producer: JoAnne Sellar

Producer: Paul Thomas Anderson

Producer: Megan Ellison

Producer: Daniel Lupi

Executive producer: Adam Somner

Executive producer: Peter Heslop

Executive producer: Chelsea Barnard

Music: Jonny Greenwood

Production design: Mark Tildesley

Editing: Dylan Tichenor

Costumes: Mark Bridges

Casting: Cassandra Kulukundis

Art direction: Denis Schnegg, Chris Peters, Adam Squires

Set decoration: Véronique Melery

Makeup and hair: Ann Fenton, Jon Henry Gordon, Paul Engelen, Emma Bailey, Lesley Noble, Daniel Lawson Johnston, Paul Paintin, Louise Young, Andrea Dowdall-Goddard, Sue Newbould, Amie Wilson, Victoria Yates, Laura Hartney, Deborah Shepherd, Jane Logan, Daisy Almond, Carolyne Martini, Holly Caddy, Amy Carter

Production supervisor: Karen Ramirez, Claudia Cimmino

Post-production supervisor: Erica Frauman

Unit production manager: Samantha Waite

Production manager: Switzerland: David Broder, Roger Neuburger

Unit manager: Drew Payne