‘Spellbound,’ like nearly all

of its subjects, isn’t quite

letter-perfect

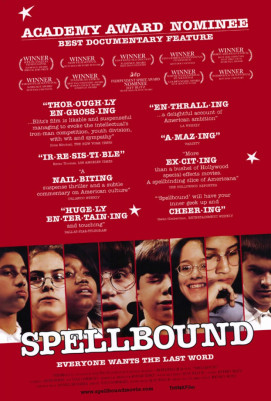

“Spellbound,” a 2002 documentary film by Jeffrey Blitz about the National Spelling Bee, does not address what seems a very crucial question: Who, in fact, gets to decide how words are spelled? Spelling is not ordered in the Ten Commandments. We have things called dictionaries. But there is more than one dictionary. They are owned by private companies. And who is employed by these dictionary companies, and how, exactly, are these people regularly verifying how the tens of thousands of words in their publications are supposed to be spelled?

According to the website of the Scripps National Spelling Bee, “Merriam-Webster Unabridged is the official dictionary ... and every word from the competition will come from this source.” How the words get to this point, and how their letters are arranged, are not grounds for objection, though there may be very reasonable grounds for objection. Does it matter that “through” is not spelled “thru”? As official style policy, the Chicago Tribune in the 1970s attempted to rewrite that word and select others for common usage, and either the public or enough editors at the paper weren’t buying it. So know your Merriam-Webster, or prepare to get dinged. And in “Spellbound,” the same title as the 1945 Alfred Hitchcock thriller, the real winner is never shown — the English major assigned to the L-M entries in Merriam’s latest update.

The Scripps National Spelling Bee, perhaps largely because of ESPN or people’s insatiable appetite for reality television, reached cottage industry status around the turn of the century. This century, not the previous one. That’s why “Spellbound” came about in the late 1990s, not in the 1950s, when no one would’ve taken it that seriously. But give someone besides ESPN credit — there is drama here. The contestants are just a letter from heartbreak. They sport their own unique uniforms, the famous numbered placards around their necks. (At some point in the 1980s or 1990s, the Scripps Bee evidently began issuing polo shirts to the contestants.) The fairest way to conduct a spelling bee would be to pronounce 10 words to a group of spellers, who write down each. Whoever has the fewest mistakes wins; in the case of a tie, we go to another round. Way back in the day, Scripps realized that it had a pre-“Jeopardy!” on its hands — youngsters hearing a word that everyone else can hear, and attempting to be perfect. It matters not if that word is twice as hard as the previous one or twice as easy as the following one. Those are the breaks.

“Spellbound” delves into the experiences of eight contestants in the 1999 Scripps National Spelling Bee, a diverse group from all around the United States. They are Nupur Lala, the eventual champion, and Harry Altman (in photo above), Neil Kadakia, Ashley White, Angela Arenivar, April DeGideo, Emily Stagg and Ted Brigham. They have at least one thing in common — they live in a county served by a sponsoring newspaper. And because of this, virtually every contestant in the National Spelling Bee — including all the ones not in “Spellbound” — has already experienced a hurricane of publicity, because newspapers cover the heck out of events that they sponsor. Even star high school jocks don’t get as much publicity as National Spelling Bee contestants. You can get a 1,600 SAT and be handed money to enroll at Harvard, and you’ll still never get as many local headlines as you will from reaching the National Spelling Bee. This newspaper interest creates what can be an awkward reality. Many kids who do well at spelling are studious introverts, but to the sponsors, the best winners are the hams.

The Scripps Bee is open to kids from fifth grade through eighth grade, not older than 16, and while it’s unknown how “Spellbound” chose its subjects (there are more than 200 contestants total in the national finals), it portrays a cross-section of interest in, and intensity for, this event. Some kids work on this perhaps year-round, their families even hiring outside help, while others seem surprised that they even made it this far. In truth, it would be better for all involved if no one prepared for it, that kids were not studying the dictionary or devoting large amounts of time to this endeavor, that contestants could show up in Washington without even bringing a dictionary and just wing it. That way the Bee wouldn’t run out of words and have to declare “Octochamps.” But the trend, evidenced by “Spellbound,” is undoubtedly going in the multi-champion direction.

In terms of gender, the Scripps National Spelling Bee appears beautifully egalitarian if not pro-female. Will “Spellbound” viewers note that there are five girls profiled and only three boys? Around 1980, the National Spelling Bee consisted of more than 70 girls and not even 50 boys. Sociologists could take a crack at those numbers. Are girls simply better at this activity? Or do many capable boys choose not to pursue it? The numbers speak for themselves, but there could be something to the idea of a social stigma, for both boys and girls. While the Scripps Bee is open to 15-year-olds, spelling bees in general, for whatever reason, tend to be associated with younger children. Maybe that is because spelling is considered too easy, or maybe it is because adults find trivia quizzes far more interesting. One revealing comment in “Spellbound” comes from 1971 champion Jonathan Knisely, who explains that winning didn’t do anything for his budding romantic life. “I think that having won something like that could be regarded as being a significant liability,” he actually says. Nevertheless, Britain’s Daily Mail asserts that “Spellbound” is “a film that made smart people cool.”

Whether “Spellbound” should’ve followed eight contestants in one year, as it did, or instead profiled several contestants who took part over the decades, is a fair question. Portraying eight kids in the same Bee sitting at home studying gets a bit tedious. The film omits mention of what for most kids is the biggest prize, a week in Washington, D.C. But how much would anyone care what it meant to a random contestant in 1986 or how the experience might’ve changed that person’s life? Knisely, if anything, seemed sheepish about his success. It seems in “Spellbound” that of the eight young competitors, one is nonchalant, two or three are hyper-focused, and the other four or five strike a healthy balance with the rest of their lives. As kids line up to take their turns at the podium and try to relax during breaks, the “Spellbound” cameras often struggle to convey adequately how each of the featured competitors is faring and where he or she stands at any given time.

One belief in “Spellbound” seems to be universal, that there is no such thing as too MUCH studying for this event. If so, contestants could wrap up the hard work before the week of competition and enjoy their time in D.C. Instead, they keep hitting the books. It seems that while someone in a multiplication bee merely needs to know how to multiply to determine any result, a spelling bee competitor has to actually look at and recite the letters of every possible word. Is our knowledge a process, the result of a mental machine that is constantly activated ... or are brain cells like library shelves, with a finite space, our minds cataloging the things we need to remember (the address I have to visit tomorrow) and discarding the things we don’t (the address I had to find three years ago), no different than recording over something on a cassette tape with something else? A spelling bee seems much more of the latter — crowding out, however temporarily, all of those baseball stats pigeonholed in the mind to memorize the construction of rare words that within months will never be seen or invoked in any way.

Someone studying for a spelling bee is, visually, almost like a person patching a leaky boat, hoping to prevent leaks not forever but for this particularly finite time of two days.

What attribute makes a great speller? Perhaps a photographic memory, but that memory has to distinguish between countless little “i” and “e” and “u” distinctions, and maybe more importantly, memory doesn’t really help with homonyms. How about an extraordinary grasp of the English language? That’s fine, but, once on stage, hearing someone speak the word to you, it’s a different ballgame.

“Spellbound” suggests (correctly) that all kinds of kids can qualify for this event and that they come to D.C. with various levels of preparation. “Spellbound” is watchable. It received an Oscar nomination for documentary feature but lost to Michael Moore’s “Bowling for Columbine.” “Spellbound” is purely ensemble material. Its characters, such as longtime bee pronouncer Dr. Alex J. Cameron of Dayton or Executive Director Paige Kimble (née Pipkin), a former champion who stepped down from the post in December, are viewed indifferently by Blitz’s cameras.

“Spellbound” does not know what to conclude of its findings and can’t be considered a great or significant documentary. There is a parallel, however, to the late-1960s drama “They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?” Both involve a contest and the prospect of a quagmire. To win at either endeavor, one has to sacrifice an enormous amount of free time. This is academic work, yet it is largely independent of schoolwork and does not produce any academic credentials or advancement. Some would say it’s a lot of effort simply to keep up with spellcheck. Is it worth it? For those who don’t win the $50,000 prize (it was $1,000 when Kimble won in 1981), it’s debatable if that time was well spent.

Studying spelling is like studying the law, a profession that may be right up the alley of many Bee competitors. Learning to spell involves memorizing how previous people have done this, how humans over centuries have gone to the trouble of listing these massive volumes of precedents that, except in rare cases, are forgotten and never overturned, because overturning requires some sort of notice and popular consensus. And, just like the law (don’t tell this to any lawyers — didn’t you notice that Mr. Hart, in “The Paper Chase,” is not trying to discover anything new; he’s just attempting to learn the same facts that elites already know), there is serious conformity required here. The last thing any contestant needs is to spend an hour arguing with someone that “sarcophagus” should really be “sarcauphagus,” even if there is decent evidence in favor of the latter, because entertaining such an insurgency would only confuse the speller and detract from memorization time. The Scripps National Spelling Bee’s website declares, “Our purpose is to help students improve their spelling, increase their vocabularies, learn concepts and develop correct English usage that will help them all their lives.” Contestants seem to think that the most important word in “Spellbound” is “ESPN.” And it’s probably not even in the dictionary.

3 stars

(January 2021)

“Spellbound” (2002)

Featuring:

Angela Arenivar ♦

Ubaldo Arenivar ♦

Jorge Arenivar ♦

Scott McGarraugh ♦

Lindy McGarraugh ♦

Concepción Arenivar ♦

Mrs. Slaughter ♦

Neelima Marupudi ♦

Nupur Lala ♦

Ms. Whitehurst ♦

Parag Lala ♦

Meena Lala ♦

Kuna Lala ♦

Ted Brigham ♦

Ms. Blair ♦

Dan Brigham ♦

Tim Brigham ♦

Earl Brigham ♦

Dorothy Brigham ♦

Emily Stagg ♦

David Stagg ♦

Suzanne Stagg ♦

Ashley White ♦

Angela White ♦

Ms. Williams ♦

Sigourney White ♦

Neil Kadakia ♦

Rajesh Kadakia ♦

Darshana Kadakia ♦

Shivani Kadakia ♦

Samye Hill ♦

April DeGideo ♦

Al DeGideo ♦

Gale DeGideo ♦

Mr. Miller ♦

Harry Altman ♦

Fay Sharit ♦

Paige Kimble ♦

Alex Cameron ♦

Mona Goldstein ♦

Frank Neuhauser ♦

Jonathan Knisely ♦

Balu Natarajan ♦

Janaky Natarajan ♦

George Thampy ♦

Vinay Krupadev ♦

Julianne Ruth

Directed by: Jeffrey Blitz

Producer: Jeffrey Blitz

Producer: Sean Welch

Additional producer: Ronnie Eisen

Music: Daniel Hulsizer

Editing: Yana Gorskaya