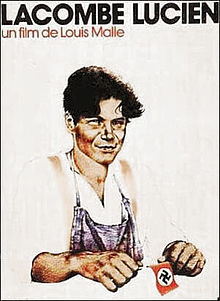

REVIEW AND ANALYSIS: ‘LACOMBE, LUCIEN’

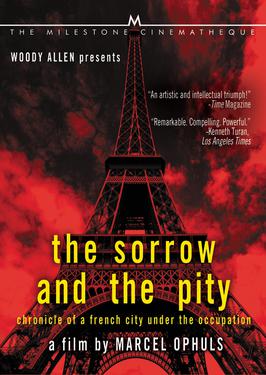

and ‘THE SORROW AND THE PITY’

A pair of French Resistance/occupation studies that lack a consent decree

“Lacombe Lucien,” released in 1974, was not the first notable film to address the French response to the Nazi occupation in a damning way. Many (including the trifecta, Roger Ebert, Pauline Kael and Vincent Canby) pointed to Marcel Ophüls’ “The Sorrow and the Pity,” a landmark work, as the prototype for analysis of this problematic chapter of French history.

But “Lacombe” stands on its own as a profound study of a universal dynamic that needs a catchy name but is best described as “group behavior.”

“Lacombe” is so richly filmed, it could pass as a movie of this century even though it was made 40 years ago. Like “The Godfather” films, it has the beautiful veneer of many ’70s films but timeless appeal. That is not even as extraordinary as the performance of its protagonist, Pierre Blaise, a non-actor discovered by Malle for this film. As Lucien, his face carries this film in a way that even many Hollywood legends can’t. Pauline Kael, impressed, wrote, “We look into it rather than react to an actor’s performance.” “Lacombe” will be driven for more than 2 hours largely by the indifference of Blaise’s expression to the atrocities and indignities around him.

Blaise’s stunning effort here gives ammunition to those who believe, as Hitchcock supposedly said, that actors are “cattle,” but it’s an even stronger argument that film actors are difference-makers; they just don’t necessarily require special training and all don’t already have Hollywood contracts. Aurore Clément, as the Jewish girl named France, similarly discovered for this film, lacks the same resonance but proved worthy of a stellar career that continues to this day. Within a couple years, Blaise would die in a car accident, a footnote to cinematic history and unknown to Americans.

Lucien’s greatest defender will not be the girl France but “The Sorrow and the Pity,” which presents several reasons why collaboration might appeal to a young Frenchman more than resistance.

We cannot choose our time. We can, only to a very limited degree, choose our people. We can emigrate to different land, a process that tends to be legally difficult and involves cutting ties with loved ones and longtime family friends and is not at all practical. No one for example moves to Canada just because an appealing government takes power and then a few years later bolts for Turkey when the Canadian government is voted out of power. People generally emigrate for reasons of livelihood, not principles. That leaves most of us to go with the flow, right or wrong. Which is where we find Lucien Lacombe in 1944 France.

Lucien’s choice will occur early in the film, its first major turning point. But notice how deftly ambiguous director Louis Malle paints the decision. Lucien is lightly educated, tough and bored. And French. His employment is very unsatisfying. He wants something to do. The Resistance seems like a good place to start. But the Resistance has concerns about Lucien, apparently age, but perhaps it’s a matter of confidence as well. Surely he could insist on taking part and win them over; they need help. Instead, he manages to fall into the circles of the local Nazi place, who are happy to take him into the fold. There is a reverse recruiting war here that would make college basketball coaches smile.

“Lacombe” indicates that people with guns give the orders. They can either be principled people who believe in freedom and human rights and delegating authority to judges and citizens. Or they can be thugs who take pleasure in pushing others around.

So many films have been made about the Nazis that “Lacombe” and “Pity,” like many others, simply skip the backstory. We know that a determined figure has rallied an unfortunately large number of people into almost unheard-of aggression, perhaps because they believe him … or perhaps simply because they see a winner and a chance to push around people they don’t like.

So much of geopolitical history is viewed through political manifesto. There are scholars, and there are believers, and then there are those who carry the weapons. History books and war-crime trials suggest the latter are the least important. “Lacombe” reminds us that sometimes, people have to pick sides, while “Pity” informs us about the uncomfortable rationale for some of those choices.

The smartest thing about “Lacombe” is when the story takes place. Many directors would start with 1940, when France suddenly had to make a lot of very big decisions. Malle’s portrait of 1944 France suggests a very benign civil war, if there is such a thing. A few are in the Resistance, a few are giving orders, and most are keeping their heads down, going about their daily business without interference from either side. The implication is that doing otherwise is asking for trouble. Malle expertly chooses a time that exposes the density of his protagonist. Informed people in France know the German reign is in trouble. Those loathing them just need to run out the clock. Even some of the Nazis in the film realize that the other side’s propaganda is worth noting. Lucien Lacombe is clueless to the state of affairs and only knows that one side wants him more than the other. At the most inopportune time, he makes a commitment that he doesn’t really care about that seals his fate.

There must be a science of group behavior. Most of us just know from experience that people tend to take far more aggressive and provocative actions when surrounded by a group. Take for example a basketball game, the home fans jeering the opposing players at the free throw line, sometimes with personal insults. The inference from “Lacombe” is that thuggery is far more effect than cause, that some of us have more of an inclination for it than others but that it isn’t unleashed by any individual until the environment calls for it.

Casual history implies the Poles fought dearly and paid an enormous price, while the French fought matter-of-factly and cut a deal. But those perceptions need to be filtered through the common enemy, who had a much higher view, even admiration, of the latter and barely more than contempt for the former. If your next-door neighbor invades your home and ransacks the place and humiliates you, that is one thing; if that same neighbor leaves the place intact and only orders you to take him to a party, that is another. That is “The Sorrow and the Pity” in a paragraph. “Lacombe” has implications far beyond the Vichy.

Lucien is introduced as a rough but modest character. He is not a rebel and does not possess a mean streak. However, he will take a devastating and uncalled-for shot at a beautiful, vulnerable creature, because he can and that’s what he does. The most important thing about this very early scene is not that Lucien is abusive but that he is insensitive. Impulses that affect most people simply do not reach his brain. He cannot be reasoned with. This makes him an ideal foot soldier and, for anyone who can’t physically overpower him, a most difficult adversary.

In a beautiful contrast, Lucien will find his rival to be Mr. Horn, an aging Jewish tailor, an elite. Why is Mr. Horn allowed to carry on? There are 2 hints, one that he is buying his freedom with regular payments that apparently can’t just be confiscated, the other that Nazis are simply less aggressive in France than in Eastern Europe. He has to defer to this young monster who will never appreciate the finer things in life, through no fault of Mr. Horn’s but because of a political earthquake a decade earlier and hundreds of miles away.

Horn is played by Holger Löwenadler, a Swede whose career was largely based in theater, chosen by Malle at the right time for the right role. His is the face of resilience and courage, professionalism, resignation and disdain. He is part of a small collection of famous film characters tasked with protecting a girl who might not want to be protected. He would probably be happy to meet more Luciens if only for the opportunity to practice his craft. Yet he knows his work is being raped, and that, as Lucien begins to make his presence felt, the same could become true of his daughter. Because of their plight, , accommodating someone such as Lucien is actually not the worst option. Horn’s daughter, named France in an obvious nod to national over ethnic identity, has a keen interest in a concept prominent in the Eric Rohmer “Six Moral Tales” films: availability. France must be secluded from the mainstream world because of the risk to her life. Her father is aware this might soon not have to be the case. But France is young and can’t see her future in such a timeline. She knows that now, she is lonely. She is certainly not fooled by Lucien’s minimal intellect. Almost immediately, through a series of questions, she can tell she’s dealing with an uneducated individual. But what surely outweighs that is that she has probably met no boys for a long time. Finally, here’s one who’s interested.

If you think this type of pressure is limited to wartime, consider a modern business where fortunes are fading and ruthless new management takes over. An example is the 2004 film “In Good Company,” a light but meaningful comedy in which veteran salesman Dennis Quaid suddenly has to answer to an upstart management team espousing a dubious synergy strategy. And guess what? Quaid’s new boss is interested in Quaid’s daughter. Fortunately, Quaid finds room to reason with Topher Grace. In “Lacombe,” Mr. Horn will suddenly crack. Pauline Kael complained about how he gives himself up; “not enough is made of the moment.” The presumption is that he was simply tired of hiding and tired of trying to protect his daughter. He is so confident in his final endeavor that the viewer believes he must have a sensational trick up his sleeve for the Nazis. When they process him, it’s an unsatisfying head-scratcher. Perhaps Malle is implying that Horn is taking his own life but with the dignity he deems necessary for the occasion.

No question, “Lacombe” relies on a very common cinematic device, the drama of outdueling the Nazis. Much of the movie is filled with suspense, wondering whose fist might be knocking on the door next, who might tell Lucien something they shouldn’t, not because Lucien cares, but because he’s bound to mention it to someone. This is the final 18 minutes of the film and much of the preceding 118.

“The Sorrow and the Pity” tells us that sometimes it was Frenchmen knocking on the Germans’ door. Some incredibly even volunteered to fight the Soviets on the Eastern front. Many French of 1940 had viewed their government as weak, and German-like philosophies were not uncommon among French military types. They saw the robust young German soldiers enter their towns and might’ve been more impressed than horrified. One person in “Pity” says the German war production was like a De Mille movie. Hitler apparently told his cautious generals that the French would never mount a stand like World War I. There’s a sense that the French were like fans of the St. Louis Browns who’d watch the New York Yankees come to town and wonder if they couldn’t root for the better team.

”Pity,” thematically a cousin of ‘Lacombe,” has much more to do with Claude Lanzmann’s “Shoah,” started in the mid-’70s and released in 1985. Both are technically considered documentaries though Lanzmann said he despises that characterization. Each excels at candor. Speakers are honest. “Shoah’ reinforces historical accounts with specifics, but ‘Pity” tells us things not in the archives, things we didn’t know. The latter left such an impression on Woody Allen that he references it in “Annie Hall” and financed American distribution of it.

First released in 1969, “Pity” coincides with the peak of American involvement in Vietnam, a country with significant French ramifications as well. One common underlying motivation in France’s dealings with both Vietnam and Nazi Germany is the fear of communism. Taken together with the Cold War, it’s possible to conclude many in the Western World of the 20th century could … could … have believed there was something worse than Nazi Germany. One wonders about the documentaries that could’ve been made in Vietnam before 1950, about people who thought the French should be resisted and their neighbors who were OK with going along. “Pity” shows, after the liberation, the humiliation of French women who dated Germans publicly getting their heads shaved. One wonders what happened after 1975 to the Vietnamese who found French rule and American influence agreeable. Somehow, the French thought control of this territory was a priority in the aftermath of World War II, an approach that would inexplicably spark the greatest American crisis of the last 70 years. By the 1990s, much of communism eroded, and China welcomed the Big Mac.

It can be inferred from “Pity” and “Lacombe” that the Germans could’ve had France had they only wanted it enough. “Pity” implies they hardly cared. It takes “Shoah” and the history professors to show the Nazis were motivated by domination, terrorism, extermination and for whatever horrific reasons preferred to practice those monstrosities in the East. France would seem to be considered not a problem to Third Reich philosophies, only insofar as the French military might be one of the few that could interfere. Roger Ebert suggested that Ophüls, despite the revelations in his film, nevertheless believes those who have not been subject to occupation have “no right to judge.”

Indeed. On the surface, “Pity” and “Lacombe” would seem to come down to free will. But we know that under these circumstances, neither Horn nor his daughter could possibly consent to what they do. And maybe not even Lucien Lacombe or Marshall Petain either. Morally, we have heard the cases. Legally, we have to throw the evidence out.

4 stars/4 stars

(December 2017)

“Lacombe, Lucien” (1974)

Starring

Pierre Blaise as Lucien Lacombe ♦

Aurore Clément as France Horn ♦

Holger Löwenadler as Albert Horn ♦

Therese Giehse as Bella Horn ♦

Stéphane Bouy as Jean-Bernard ♦

Loumi Iacobesco as Betty Beaulieu ♦

René Bouloc as Faure ♦

Pierre Decazes as Aubert ♦

Jean Rougerie as Tonin ♦

Cécile Ricard as Marie ♦

Jacqueline Staup as Lucienne Chauvelot ♦

Ave Ninchi as Mme. Georges ♦

Pierre Saintons as Hippolyte ♦

Gilberte Rivet as mére de Lucien ♦

Jacques Rispal as M. Laborit ♦

Jean Bousquet as Peyssac ♦

Franz Rudnick ♦

Jean-Louis Blum ♦

Claude Marcan ♦

Jean Maurat ♦

Gabriel Cabessut ♦

Mimi Juskiewenski ♦

Albert Tillet ♦

René Thauran ♦

Mimi Juskienwenski ♦

Jean Mourat ♦

Roger Riffard ♦

Walter Seldmayer ♦

René Thouron

Directed by: Louis Malle

Written by: Louis Malle

Written by: Patrick Modiano

Producer: Louis Malle

Producer: Claude Nedjar

Cinematography: Tonino Delli Colli

Editing: Suzanne Baron

Casting: Catherine Vernoux

Production design: Ghislain Uhry

Set decoration: Henri Vergnes

Costume design: Corinne Jorry

Makeup and hair: Janou Pottier, Nguyen Thi Loan

Production manager: Paul Maigret

Unit manager: Roland Thénot

“The Sorrow and the Pity” (1969)

Featuring

Georges Bidault ♦

Mathaus Bleibinger ♦

Charles Braun ♦

Maurice Buckmaster ♦

Emile Coulaudon ♦

Emmanuel d'Astier de la Vigerie ♦

Count René de Chambrun ♦

Christian de la Mazière ♦

Darquier de Pellepoix (archive footage) ♦

Jacques Doriot ... (archive footage) ♦

Colonel R. du Jonchay ♦

Jacques Duclos ♦

Lord Avon ♦

Sgt. Evans ♦

Marcel Degliame-Fouche ♦

Raphael Geminiani ♦

Alexis Grave ♦

Louis Grave ♦

Marius Klein ♦

Georges Lamirand ♦

Pierre Laval (archive footage) ♦

Pierre Le Calvez ♦

Mr. Leiris ♦

Dr. Claude Levy ♦

Pierre Mendès-France ♦

Cmdt. Menut ♦

Elmar Michel ♦

Mr. Mioche ♦

Marcel Ophüls ♦

Denis Rake ♦

Henri Rochat ♦

Paul Schmidt ♦

Mme. Solange ♦

Edward Spears ♦

Helmuth Tausend ♦

Roger Tounze ♦

Marcel Verdier ♦

Walter Warlimont

Directed by: Marcel Ophüls

Written by: Marcel Ophüls

Written by: André Harris

Producer: André Harris

Producer: Alain de Sedouy

Cinematography: André Gazut, Jürgen Thieme

Editing: Claude Vajda

Production director: Wolfgang Theile

Presenter (2000 version): Woody Allen