Woody Allen doesn’t know who ‘Interiors’ is about, so the movie decides it for him

The most interesting development in Woody Allen’s “Interiors” is a character’s decision to make the same exit as Bruce Dern in “Coming Home,” a completely unrelated movie also released in 1978, about six months earlier than “Interiors.”

Coincidence? Probably. Neither Pauline Kael nor Gene Siskel nor Roger Ebert mentioned it. And other films have done that scene too, before and after 1978, including the 1973 film “The Long Goodbye.”

The significance of this scene, however, varies greatly between “Interiors” and “Coming Home.” Both of the characters have experienced recent trauma. Comparing that trauma is a little ridiculous. Each character is choosing a method in which there is the chance of return. In “Coming Home,” this scene is the outcome of an important battle. In “Interiors,” is it even necessary? These conversations, revelations, accusations and faults are going to continue forever, regardless of who is around to take part in them. The movie has no starting point and no endpoint. There will be other momentous events in the family — deaths, marriages, illnesses, divorces, babies, gay introductions — that will provide the grist for future variations of this story. “Interiors” is a success of the sum of the parts, a merry-go-round of interesting interactions in every scene, and far from a triumph of the whole. As Vincent Canby put it, “I haven’t any real idea what the film is up to.”

There’s an intriguing critical divergence about the ethnicity of this family. Pauline Kael wondered, “Are we expected to ask ourselves who in the movie is Jewish and who is Gentile? ... Surely at root the family problem is Jewish.” Kael observes, “The two mothers appear to be the two sides of the mythic dominating Jewish matriarch.” That was very prescient, as those two actresses, Geraldine Page and Maureen Stapleton, each scored Oscar nominations. Kael deems “Interiors” the “ultimate Jewish movie.”

Gene Siskel though writes in his three-star review, “The family in question is rich, white, probably WASP, but maybe Catholic.” Roger Ebert gave “Interiors” four stars but, in a rare miss, makes no mention of ethnicity and appears to regard the family as generic.

Vincent Canby bluntly admitted, “I’m not even sure whether the family in the movie is Protestant, Catholic or Jewish.”

Canby suggests that “Interiors” could possibly be “a Brooklyn Jewish boy’s fantasy about middle-class American Protestantism,” which would be taking the scenes involving a church and pastor too literally. Kael seems most on target. Allen impressively is breaking convention, not just in a comedy such as “Annie Hall” but this time in a (mostly) drama, giving us “ultimate Jewish” themes, however universal, in a setting cleverly cloaked as something else.

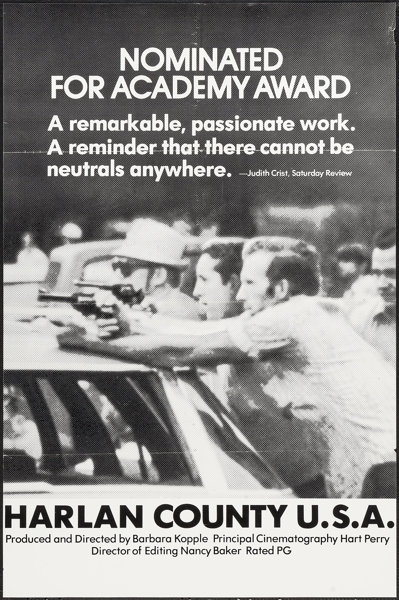

Allen’s audience is the college-educated professional set, the Café Society, people who have read the classics and studied history and obsess over issues far removed from putting food on the table. That niche is narrower than you might think, and it makes Allen a destination for moviegoers whom Hollywood doesn’t care about in the slightest — people of middle age. (Yet, the same audience is also more interested in “Harlan County U.S.A.” than the working class is.) Kael, Ebert, Canby and Siskel all note Allen’s interest in Ingmar Bergman as well as Eugene O’Neill, but remember that unlike Bergman, Allen made a nice living and considerable cachet as a funnyman before venturing into, as Canby put it, the “serious drama” of “Interiors.” Most of Allen’s films are comedies, and all have comedic moments. He is unique in cinema history. Nicole Holofcener comes to mind as someone who reaches the same audience, but not many others do.

Allen described “Interiors” this way to Siskel in a 1978 article: “The movie revolves around several different problems, one being the problem of people not being able to feel anything for one another. But the central issue is examining what choices people make to cope with the facts of their existence, what defenses they choose to employ to deal with the fact that life is tough, that we all have trouble relating to people, that we age, that we die, that we have trouble relating to members of our family and to the people we marry.”

The problem with everything Allen describes there is that very little of it is visual. Yes, the home decor is stunning, and the way people are seated around a table or standing in a room can say much about what they’re thinking. But that only works so far; to supply a lot more needed details, characters must announce résumés — and each other’s faults — to each other so the audience will know what they are talking about.

No matter how much a film attempts to be an “ensemble,” dramatic forces prevail. Someone has to be the protagonist. In “Interiors,” that character is Joey, played by Mary Beth Hurt (sometimes her first name is spelled “Mary Beth,” other times, “Marybeth”). She is the least successful of the three daughters and the most troubled by the family’s annoyances. She announces early that her mother is “very sick,” although nothing else seems to indicate as much. Whether family dysfunction is the cause of Joey’s career uncertainty or her career uncertainty has caused her to take her family dysfunction too seriously is a good chicken-and-egg question. Kael writes that Joey resembles a perpetual student and her hair is “like shiny armor” that says “hands off.” Joey would succeed by achieving some kind of newfound understanding with her parents and the realization that on some important levels, she’s doing better than her sisters. Allen will ultimately appoint Joey the chosen one, in a beach scene that will trigger all kinds of revelations.

As the poet Renata, Diane Keaton, who stole the show in “Annie Hall,” perhaps gave herself the short straw. Siskel writes that “of all the roles in the film, the weakest, the poorest written, the most unclear, belongs to Diane Keaton. I don’t know what her character’s problem is, other than selfishness.” Kael writes that Keaton gives a “thoughtful” and even “very courageous” performance, appearing with “dead-looking hair” and “dry and pasty” skin while her Hollywood sister Flyn in this film gets the glam look.

Canby says Keaton had “the most difficult role” of the film, playing a poet, which is a crucial indictment of Allen’s “Interiors” characters. Most of them are writers. For some reason, moviemakers keep doing this. If the characters are painters, you can see how good their work is. If they are writers, you cannot. Why do writer characters keep surfacing with lead roles in films? Probably because a lot of writers can easily identify and write the dialogue in ways that they might talk or wish to talk or did talk at Princeton or Greenwich Country Day.

With writer characters come a batch of obnoxious clichés. A common one is the writer who is struggling and who is unhappy that his/her significant other didn’t seem totally honest about how much he/she liked the book. That complaint this time falls to Richard Jordan’s Frederick, Renata’s bully of a husband who far more resembles a lumberjack than author. This idea is so unique that it not only is the plot driver of an acclaimed 2023 film, “Anatomy of a Fall,” it also plays prominently in a 2023 film by Nicole Holofcener.

Flyn, the actress played by Kristin Griffith, is beautiful but unaffected by the history of behavior that torments her sisters. She made a clean break a while ago. She has one of the world’s most desirable jobs but rather than radiating happiness, hers is a happy-to-be-here persona, “here” meaning Hollywood, not New York, where her family bickers. Her character is quietly significant because, on the battlefield that is this family, she has given up. She (somehow) has no significant other and indulges in substance abuse. She is clearly not taken by method acting nor is she compelled to perform when not on camera; it’s obvious that people told her “You’re beautiful, you should go to some auditions,” and she figured, “Why not?”

Two characters in “Interiors” who are not writers may or may not be responsible for everyone’s unhappiness. “Interiors,” like “Ordinary People” or the 2023 film “The Iron Claw,” strongly suggests that attractive people who are highly successful can be destructive parents who nonchalantly leave self-doubt and self-loathing in their wake. Those other two films have a blunt edge for delivering those observations. “Interiors,” it is agreed, is not a comedy, but somehow must get the point across with a lighter touch. As Kael says, “‘Interiors’ isn’t Gentile, but it is genteel.”

The villain in “Interiors” initially seems to be the mother, Eve, played by the screen legend Geraldine Page. Page made this movie in her early 50s. She looks considerably older, like a character from the 1950s. Her husband announces that he is 63; it would be well within artistic license if Eve looked to be late 50s. It’s clear from her opening appearance that Eve can’t resist pointing out her daughters’ faults or correcting them. Unfortunately, she has some kind of trouble with life’s ordinary relationships, to the point she can only function well when doing her job, which is sharply decreeing how a home should look.

Gradually, we learn that the dad, Arthur, may be equally at fault. A corporate lawyer, he is shown conducting explosive family discussions like a board meeting. Characters do not speak of financial trouble but there is a hint of an undercurrent throughout “Interiors” that financial aspirations fuel the tension, that the endgame is shiny houses regardless of whether there’s rotting within. Arthur makes a big announcement at the dining-room table and will admit, at another time in the film, that he wasn’t totally truthful about his expectations in his comments, because, he correctly says, his wife wouldn’t have taken it very well.

It could be inferred Eve is too much to deal with, or it could be inferred that he is quick to cut and run. Arthur would say that what he is announcing is not negotiable. He is simply making a change to his life and is doing his family a favor by letting them know. Like many movies of family drama, these characters exist in a bubble, there are no grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins or even close friends who might offer a constructive opinion on the proceedings.

Why is Arthur making this announcement in front of his daughters? He has lost whatever connection he once had with his wife and simply isn’t comfortable having conversation alone with her. In the opening couple minutes of the film, Allen depicts, in separate frames, Arthur and two of the daughters looking out of different windows. (Renata will put her hand to the window like the boy in Bergman’s “Persona.”) Arthur has his back to the camera. To whom he is speaking is unclear. He summarizes, in a couple of soundbites that are hard to hear because of his position, the rise and fall of his marriage. He met Eve when he dropped out of law school (another character will later explain that she financed his way back through it). In the beginning, he says, it was “so perfect, so ordered,” but he came to realize it was actually “so rigid.”

He continues that all of a sudden, Eve’s was “a face I didn’t recognize.”

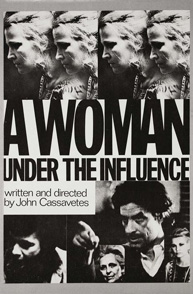

Arthur’s comments suggest that “Interiors” will take the approach of “A Woman Under the Influence,” in which family members must react to a beloved person slipping into madness. Both mothers will spend time in a sanitarium. But Eve’s illness is not nearly as obvious or debilitating as what befalls Mabel in “Influence.” Furthermore, while Mabel inspires pity, Eve inspires grudges and resentment. Is her illness about gaining attention? Does anyone actually want to save Eve? Yes, we ultimately learn, and it nearly costs someone else their life. Allen, as the movies often do, picks the younger person to make it through.

Arthur’s remedy for the rigidity of a long marriage is the instant companionship he finds from Pearl. Allen is probably being a little too generous to Arthur — a more likely scenario would probably have him finding a new mate around his daughters’ ages. Pearl is warm-hearted, non-judgmental and fun to be around, which Arthur has realized. The daughters can’t accept it, as they test her at a family dinner about enjoying the Greek ruins and classic literature, dismayed by her responses. They are first surprised to hear that one of Pearl’s sons “runs an art gallery,” only for her to bluntly admit it’s a “junk” concession stand at Caesars Palace in Vegas. “She’s a vulgarian!,” Joey will blurt in one of the movie’s funny lines.

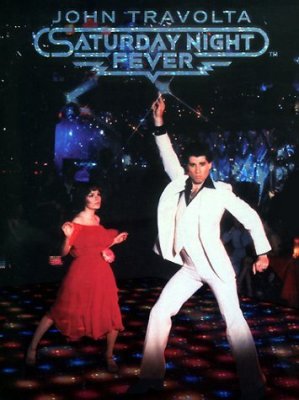

Often clocking in around an hour and a half, Allen is perhaps the best film editor in history. “Interiors,” like most of his works, is impressively tight and pointed. But there are lapses. Joey at one point announces she is pregnant, which is handled by a brisk conversation during an even brisker walk. More significant is the curious interaction between Flyn and her brother-in-law Frederick. She does seem to enjoy his company. Does she really enjoy it ... or is Flyn, too, capable of passive-aggressive maneuvering against one of her sisters. Her affection inspires an alarming attack in a car along the lines of Tony Manero in “Saturday Night Fever.” She seems not totally surprised (she is a star in Hollywood, where these incidents, we’ve come to learn, are somehow quite common), but she is not receptive, and her reaction suggests this was not her intended outcome. Kael notes that when one character lovingly admires a vase, another character is bound to break it.

“Interiors” may reluctantly be a movie about Joey, but it was Page who scored the biggest prize, an Oscar nomination for best leading actress, one of the film’s five, a very impressive tally. Page lost the Oscar to Jane Fonda of “Coming Home.” Stapleton received a supporting actress nod (losing to Maggie Smith of “California Suite”), Allen received nominations for a couple other big prizes, best director and original screenplay (the winners were Michael Cimino of “The Deer Hunter” and Nancy Dowd, Waldo Salt and Robert C. Jones of “Coming Home”), and Mel Bourne and Daniel Robert were nominated for art direction-set decoration (they lost to Paul Sylbert, Edwin O’Donovan and George Gaines of “Heaven Can Wait”).

Those judgments seem well-deserved and fair. There is great filmmaking in “Interiors.” But Allen has made a play, not a movie. And he can’t give his own serious drama an edge anything like “Coming Home.” One film technique, flashbacks, only throws off the pace. His characters have to tell us what’s going on. They do not have enough to show, and his quick-witted dialogue, misplaced in this kind of film, is all too available to fill in the gaps. Too often, his scenes feel like they need a joke. These people are not to be cheered or despised, they exist as mechanical vehicles for airing all kinds of typical grievances. “Interiors” is surely a tragedy but doesn’t feel enough like it. In some movies, a woman famously doesn’t want to be rescued. This time, we’re not so certain.

3 stars

(January 2024)

“Interiors” (1978)

Starring

Mary Beth Hurt

as Joey ♦

Kristin Griffith

as Flyn ♦

Richard Jordan

as Frederick ♦

Diane Keaton

as Renata ♦

E.G. Marshall

as Arthur ♦

Geraldine Page

as Eve ♦

Maureen Stapleton

as Pearl ♦

Sam Waterston

as Mike ♦

Missy Hope

as Young Joey ♦

Kerry Duffy

as Young Renata ♦

Nancy Collins

as Young Flyn ♦

Penny Gaston

as Young Eve ♦

Roger Morden

as Young Arthur ♦

Henderson Forsythe

as Judge Bartel

Directed by: Woody Allen

Written by: Woody Allen

Producer: Charles H. Joffe

Executive producer: Robert Greenhut

Cinematography: Gordon Willis

Editing: Ralph Rosenblum

Casting: Juilet Taylor

Production design: Mel Bourne

Set decoration: Mario Mazzola, Daniel Robert

Costumes: Joel Schumacher

Makeup and hair: Romaine Greene, Fern Buchner

Production manager / production supervisor: John Nicolella