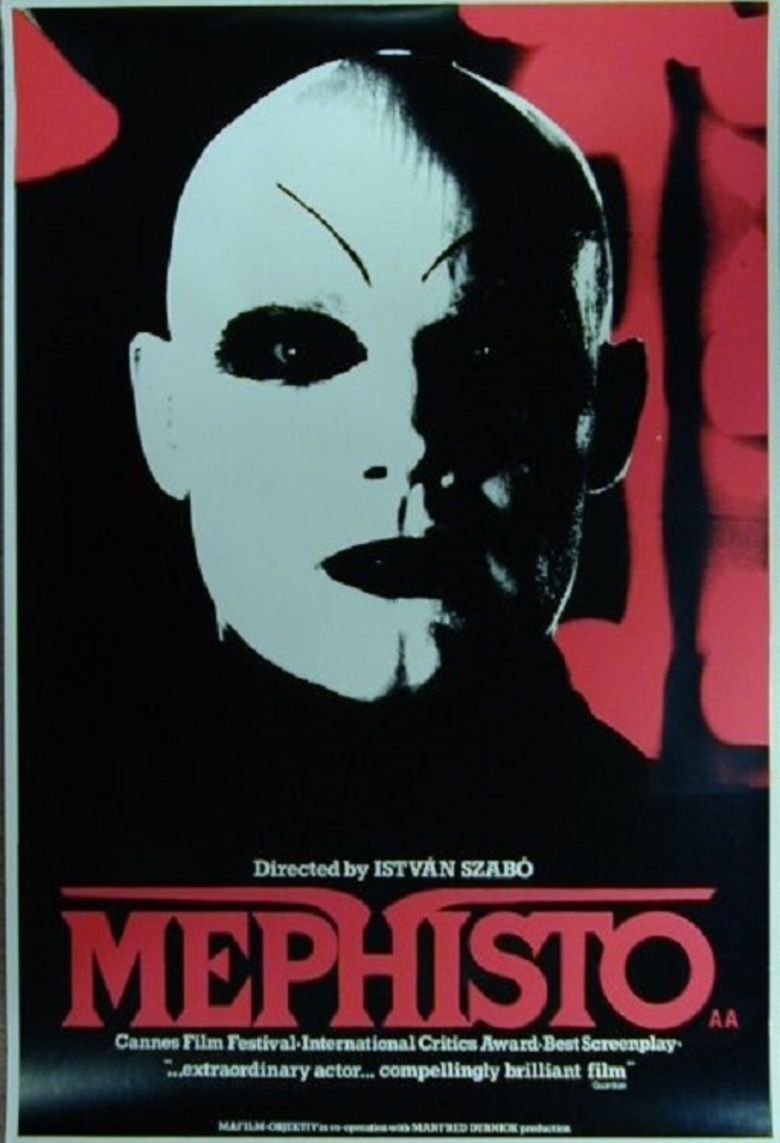

‘Mephisto’: A conscience-free actor bedevils a tough crowd

Politics and the arts have a troubled coexistence. Most noteworthy was Hollywood’s blacklist era. There was Richard Nixon’s enemies list, which included Paul Newman. Not too long ago, a member of the most popular American theatrical production in recent time made a special statement to Vice President Mike Pence after the curtain dropped.

“Mephisto,” a fascinating 1981 character study by Hungarian director István Szabó, puts the very awkward relationship between artistic excellence and a right-wing regime on a crash course, flirting with intriguing potential detours but never losing sight of its path. It is a contender for the finest film about artistic purity.

Szabó’s great success is that viewers, just like the supporting characters, will spend the entire film questioning Hendrik Höfgen’s motivations. Is he betraying art ... or saving it. The answer need not be binary.

“Mephisto” presumes, as do most films that invoke Nazi Germany, that the viewer already knows what happened in the 1930s. That thugs took over a powerful and proud country of many elites, committed nearly unspeakable horror, glorified themselves, and got wiped out. The armbands and flags are commonplace, including on the movie’s posters. But there aren’t book-burnings, trains and death camps, or even a mention of “Hitler.” (Pauline Kael noted they simply say “Heil.”) There is a tradeoff with that approach. It allows Szabó to, figuratively, cut to the chase throughout the gripping second half of the film. But it also limits what Szabó might show, requiring characters to merely speak of critical moments or philosophies of the Nazi regime that lead to key events, such as Hendrik briefly relocating to Hungary and his wife fleeing to France.

“The Last Metro,” a film made about the same time as “Mephisto,” deals with Nazi interest in a French theater. Why were the Nazis concerned about the arts? “Mephisto” does not address this question but at least introduces it. Perhaps regimes fear that theatrical productions can cause civil unrest. Or maybe autocrats simply identify the artistic community, no matter what the creation, as bitter ideological foes who must be defeated, and the easiest way is to co-opt or close their productions.

But it’s not that simple. As we see in “Mephisto,” arts, probably like athletics, are viewed by all parties as a powerful symbol of a nation’s stature. The Nazis are in a Catch-22, driving out their country’s most talented artisans while asserting Germanic cultural supremacy over the rest of the world. Because of the latter incentive, they will allow “Hamlet” (the gold standard of Shakespeare productions, according to filmmakers), but only with a caveat of a speech (delivered by Höfgen) pretending how the plot represents the finest values of Deutschland. The Nazis can’t shut the theaters; it would be an admission they have no cultural flourish.

Most of the censoring or banning of films is probably on sexual or religious grounds, but under many governments, depictions of workers or policies can draw regulatory heat. State film skepticism is hardly limited to the right. China banned “Back to the Future.” In the Soviet bloc, movies had to pass muster with an arts chieftain. Roman Polanski wrote of having to resubmit the script for “Knife in the Water” to the Ministry of Culture and “remedy its deficiencies.”

We know one thing Hendrik Höfgen’s got going for him — artisans are fleeing Germany, so there are openings at the top. We only know the artisans are fleeing because it is mentioned in dialogue, but Hendrik’s rise as party favorite is highly effective visually. As Hendrik, Klaus Maria Brandauer, an Austrian who also appeared in “Out of Africa,” resembles the American actors John Saxon and Kevin Spacey but with a more impish smile that serves him wonderfully as Mephisto. We see him making friends, or even marriages, with whoever can open another door, and we see him thread the needle in his conversations with Nazis, deferential, with a certain degree of assertiveness. Pauline Kael wrote that Brandauer evokes Marius Goring and Albert Finney. Brandauer stamps Hendrik on the list of notorious cinematic professional climbers that spans, among others, Barbara Stanwyck in “Baby Face,” Anne Baxter in “All About Eve” and Tim Robbins in “The Player.” Roger Ebert suggested “Mephisto” as a “companion film” to another European film of a few years earlier, “The Marriage of Maria Braun.”

The important Nazi in “Mephisto” is the Nazi cultural boss, played by Rolf Hoppe and referred to as “General” throughout the film. He strongly resembles Werner Klemperer’s Col. Klink of “Hogan’s Heroes” and comes across as something of a wily buffoon. A few other Nazis with speaking roles are played by the type of character actors whose presence implies something bad is about to happen. All of these characters, with one exception in a forest, only speak of their evil rather than demonstrating it, such as their references to “foreign” elements. A few scenes of people being escorted into cars should either be a lot more frightening or a lot more cuttable. Required to show what might happen if Hendrik were to resist the authorities, Szabó cleverly comes at Hendrik from several directions, suggesting that if you attempt to incite some kind of resistance, you are likely to be part of some kind of car crash or suicide. Unfortunately, people pleading with someone to sign a piece of paper or attend a meeting is simply not strongly visual.

Pauline Kael saw that Hendrik “gives the impression of being homosexual” and that his two wives “appear to have been lovers.” But Kael’s review notes Hendrik has no gay relationships; she suggests Szabó wanted a broad portrayal of an artist. It’s also possible Szabó is lampooning the Nazis as a secret gay haven, people different on the inside than how they performed on the outside.

To Hendrik Höfgen, marriage is meaningless, a line on the curriculum vitae. His most convincing relationship is with a biracial German woman who is not his wife. There is something kinky but authentic about their pairing, artistic types who “get” each other on some important level, if not a social one. Szabó takes a risk here with an early, lengthy scene depicting the two gyrating awkwardly around a room in partial nudity. Perhaps they are blowing off steam, like ballplayers taking batting practice after a game. It’s a strange connection of two people who are, or will be, on the fringes of society, but it works. Nevertheless, their scenes appear something more like out of the 1980s (“Fame”?) than the 1930s.

Including a biracial character in a significant role is a great call by Szabó, whose characters all look different enough that there’s no confusing them in the early stages of the movie, before the momentum picks up in the superior second half. The casting does get a bit crowded with the presence of Lotte Lindenthal, the fourth woman of significance. She is the one character who nearly falls through the cracks; Szabó apparently deemed her essential as Hendrik’s go-between with the Nazis rather than have Hendrik communicate with the Nazis directly.

Hendrik Höfgen is based on the German actor Gustaf Gründgens, who appeared in “M” and also in the 1960 West German film “Faust.” Kael complains that “Mephisto” “fudges the issue of whether Höfgen is really a great actor.” It seems that this particular theater era in Germany has to be marked with an asterisk, such as when American pro football employed replacement players and it might not’ve been clear whether some of the guys scoring touchdowns were actually any good. Hendrik seems competent but not extraordinary, unless you count his accomplishments offstage. He wants to be regarded as a great actor. To do so, he has to convince the Nazis he’s on their side and convince his friends and associates that this is real art. Neither party is fully convinced, but things work out for him. There are several reasons to dislike Hendrik. There is also the likelihood that if he fled, Germany’s marquee attraction would’ve been some stone-faced fellow wearing an armband.

Selling one’s soul has been done before but rarely with this kind of visual. Michael Corleone merely started wearing hats. The Faustian reference, complete with white mask, resonates powerfully if too easily in “Mephisto,” especially when Höfgen visits the General’s box at the theater between acts and the crowd takes note. The Nazis in the film are remarkably static. Once they begin to appear, they maintain a monotonous backdrop, never encroaching deeper into the theater scene nor being surprise-attacked such as in “The Dirty Dozen” or “Inglorious Basterds.”

“Faust,” by the way, was submitted by West Germany for the foreign language Oscar of 1960 but was not nominated. “Mephisto” fared far better, winning the Academy Award for that category in 1981. Ebert wrote that the film “richly deserved” the honor.

There is a sort of tragedy involved in “Mephisto” — that hardly any Americans can see it. It’s not available on streaming services. DVDs are available on the Internet, but of non-American region. The best bet for many is to find a VHS tape with English subtitles.

Forced to choose sides is a compelling film narrative. But maybe, to many people, it’s not actually a tough call. There are hints in “Mephisto” of Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Conformist” and Louis Malle’s “Lacombe, Lucien.” Kael says Gründgens “was cleared after the war and went on performing.” “Mephisto” might be telling us something we really don’t want to know, that maybe ideals are more common in speeches than everyday life.

4 stars

(April 2020)

“Mephisto” (1981)

Starring

Klaus Maria Brandauer

as Hendrik Höfgen

♦

Krystyna Janda

as Barbara Bruckner

♦

Ildikó Bánsági

as Nicoletta von Niebuhr ♦

Rolf Hoppe

as Tábornagy

♦

György Cserhalmi

as Hans Miklas ♦

Péter Andorai

as Otto Ulrichs ♦

Karin Boyd

as Juliette Martens ♦

Christine Harbort

as Lotte Lindenthal ♦

Tamás Major

as Oskar Kroge, színigazgató ♦

Ildikó Kishonti

as Dora Martin, primadonna ♦

Mária Bisztrai

as Motzné, tragika ♦

Sándor Lukács

as Rolf Bonetti, bonviván ♦

Bánfalvi Ágnes

as Angelika Siebert, naiva ♦

Judit Hernádi

as Rachel Mohrenwitz, drámai szende ♦

Vilmos Kun

as Ügyelõ ♦

Ida Versényi

as Súgó ♦

István Komlós

as Kis Böck, Öltöztetõ ♦

Sári Gencsy

as Bella Hilfgrin ♦

Zdzislaw Mrozewski

as Bruckner, tanácsos ♦

Stanislava Strobachow

as Tábornokné ♦

Károly Ujlaky

as Sebastian ♦

György Bánffy

as Faust ♦

József Csör

as Joachim, jellemszínész ♦

Christian Grashof

as Cesar von Muck ♦

Teri Tordai

as Laura, szobrásznõ ♦

Hédi Temessy

as Egy nagybankos neje ♦

David Robinson

as Davidson, kritikus ♦

Géza Kovács

as Müller, kritikus ♦

Hans Ulrich Laufer

as Radig, szerkesztõ ♦

Margrid Hellberg

as Fiatal énekesnõ ♦

Kerstin Hellberg

as Fiatal énekesnõ ♦

Irén Bordán

as Filmszínésznõ ♦

Oszkár Gáti

as Filmszínész ♦

Tamás Balikó

as A Tábornagy szárnysegéde ♦

Ödön Rubold

as A Tábornagy szárnysegéde ♦

István Palotai

as A Tábornagy szárnysegéde ♦

Bertalan Papp

as A Tábornagy szárnysegéde ♦

Rózsa Balogh

♦

Mónika Bognár

♦

Bolykovszky Béla

♦

Erzsébet Czeglédi

♦

János Dömölky

♦

Mária Fekete

♦

Katalin Fráter

♦

Tamás Fésüs

♦

Oszkárné Gombik

♦

Prof. Martin Hellberg as Professor ♦

Magda Kalmár as Soprano singer (singing voice) ♦

István Karsai ♦

Bazsa Kiss ♦

Katalin Korancz ♦

Géza Laczkovich ♦

György Lencz ♦

József Lukácsi ♦

Sándor Majoros ♦

Lajos Mezey ♦

Vilmos Mosóczy ♦

Rita Máté ♦

Tamás Philipovics ♦

Tamás Philippovits ♦

Fruzsina Pregitzer ♦

Gizella Ramshorn ♦

András Sebestyén ♦

Csilla Strébely ♦

Mihály Szacsky ♦

Erzsi Sándor ♦

Sólyom Katalin ♦

Péter Tihanyi ♦

Tamás Tóth ♦

Vidor Török ♦

Katalin Varga ♦

János Xantus ♦

Imre Zvoronics

Directed by: István Szabó

Written by: Klaus Mann (novel)

Written by: Péter Dobai (screenplay)

Written by: István Szabó (screenplay)

Producer: Manfred Durniok

Music: Zdenkó Tamássy

Cinematography: Lajos Koltai

Editing: Zsuzsa Csákány

Art direction: József Romvári

Set decoration: Nagy János

Costumes: Ágnes Gyarmathy

Makeup: Edit Basilides, Ábrisné Basilides, Rozalia Szegedi

Production manager: Lajos Óvári

Stunts: Béla Unger, Bela Kasi, Lou Horvath, Ferenc Novinecz

Special thanks: Barbara Stone, David C. Stone