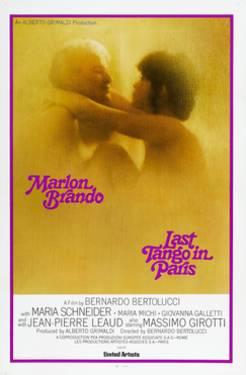

In Truffaut’s ‘The Last Metro,’ there’s plenty of room in the basement, not so much in the billing

The minimal drama of “The Last Metro” occurs in a cellar, and countless necessary details are spoken, not shown. Somehow, when its 131 minutes are complete, you wish there were more.

That’s the magic of François Truffaut and Catherine Deneuve, cinematic giants who might’ve just dozed through this one yet still turned it into a pleasant dream.

The Holocaust is a profound movie theme, and France is in a unique position. The Nazis committed atrocities there; unfortunately, not all of the locals cringed. Observations to that effect were made a decade before “The Last Metro” in the form of “The Sorrow and the Pity” and “Lacombe, Lucien.” It’s payback time.

“The Last Metro” is an assessment not only of French artistic pride but life at a theater. The latter angle dovetails with “Day for Night,” Truffaut’s 1973 Oscar-winning gem about all that can go wrong on a movie set. Unfortunately, the embattled-play production has been tried as a film many times, and Truffaut’s insights here are inconsequential.

So back to the occupation. “Metro” (its French title is “Le Dernier Métro”) purports to show how the artistic community buoyed the French and, through dedication to culture and force of will, kept the Nazis and collaborators at bay. The driving force is Lucas Steiner. This is a problem because Heinz Bennent, who plays Lucas and apparently served in the Luftwaffe in WWII, is not one of the film’s big stars and can’t be allowed to carry it. Lucas is a fearless Paris theater owner who happens to be Jewish and is compelled to disappear, leaving the latest production in the hands of his wife, Marion. So many things could easily trip up Lucas’ theater and his life. But we can’t help but be more concerned about his life than his theater, and so the backstage drama about how to say the lines and whom to date and how to get the right permits is a series of annoyances of interest only to Daxiat, the French “critic” who looks far more like a detective than writer and seems to serve mostly as a Nazi watchdog.

At one point, Lucas puts on a fake nose and speculates about what it means to look Jewish. Truffaut initially had doubts about casting Bennent, a German, as a Jew but decided French audiences didn’t know him and by the way, he’s a “great actor.”

Boxed in by his setting, Truffaut follows the actors around the stairs, hallways, offices and dressing rooms of the theater. There’s a sense that not only are the Nazis watching, but some of the cast and crew have eyes for each other. No one enjoys any privacy except for Lucas; we learn early on that he hasn’t fled but is hiding in the basement, a parallel to the story of Anne Frank.

The location is a filming constraint, but a bigger problem is Truffaut’s relentless information-speak. Characters repeatedly tell each other things that should be shown, if possible, but Truffaut hardly even tries. When characters venture onto the streets for cozy or clandestine meetings at restaurants and nightclubs, the scenes look to be straight from a studio.

Lucas is remarkably nonchalant about his plight. He jokes about the authorities as though he risks receiving a speeding ticket. That irritated Roger Ebert, who complains in his 3-star review, “Nobody seems to really understand that there’s a war on, out there.” Which makes it all the more interesting when one subtracts the Nazis altogether. What’s left is filmdom’s typical assessment of theater drama — a desperate production in which valiant but beleaguered performers/directors/owners, on the verge of going belly up, are compelled by the magic of drama to come through in some sort of redemption. In “The Last Metro,” the trick is buying time. Eventually, the sentiment seems to be, the Allies are going to get there, or the Nazis are going to move on to other concerns, and someday, theaters will again operate freely with Jews, homosexuals or anyone else. Once that happens, we can revert to more timeless concerns of the acting troupe, none more important than the love affair.

As Marion, Deneuve proves it’s possible to be both wooden and radiant. She carries this film grandly but can’t seal the deal. Whenever there’s a question about a permit, she’s always got an answer. When it comes to whom she loves, she’s got none.

Many movie couples have no business being together. Lucas and Marion share a business acumen and mutual respect but little more. The first half of the film is driven by an escape plan. Lucas appears to have no say in it; Marion repeatedly visits to tell him what he needs to do. Is he the one who should be going, or she? Perhaps they’d leave for Spain together, but “To be safe, I’ve got to play at least the first 100 performances,” Marion explains. Deneuve won’t convince us whether Marion is being inspired by Lucas’ plight to fight for the theater at all costs or is simply disheartened that her marriage threatens her livelihood.

Gérard Depardieu, who took the role of upstart actor Bernard Granger reluctantly, is supposed to round out the love triangle, but his strange and laborious opening sidewalk flirt strongly implies Bernard doesn’t know what he’s doing, and when it’s time to impress Marion, it’s hard to believe she cares. He’s a romantic artist; she’s the ultimate businesswoman. Granger has to be shown as the Resistance, otherwise, he would fall well short of Lucas’ standard of courage. Lucas, who is listening to the rehearsals from below the stage, at one point urges Marion to be “more sincere” in the “only love scene in the play,” a comment with subtext indicating he can sense she’s holding something back.

We know where things are headed just by looking at the cast list. Having successfully installed himself as the hero of “Day for Night,” Truffaut should’ve realized that a director’s role in a make-or-break production can’t be minimized. Lucas slowly learns that despite his best efforts, neither the curiously titled “The Vanished Woman” nor “The Last Metro” belongs to him. It’s not clear what he accomplishes or saves.

The theater’s squishy position is outlined in a lengthy sequence at the beginning. Granger, an up-and-coming actor of some renown, shows up at the theater just in time to see Deneuve reject a Jewish actor who lacks the proper papers. “Marion Steiner doesn’t want Jews in her theater,” he hears her say.

But Bernard, mildly sympathetic toward this fellow, is persuaded to stay and assured he is a good get for the production. While Bernard assesses the script and the females in the production and his own role in the Resistance, Marion repeatedly visits the cellar to update Lucas with setbacks in the apparent escape plan. First, a trusted handler is arrested, then, the Germans invade Free France. And their money might not be enough; they might need to sacrifice the family jewels. Lucas’ lack of interest in these developments is about as authentic as his sudden desire, like that of Albert Horn in “Lacombe, Lucien,” to go visit the Nazi authorities and straighten everything out, as if Truffaut is desperate just to get this man out of his film so that he can turn it over to Deneuve.

In “Day for Night,” the movie they are filming, “Meet Pamela,” has to be terrible, if for no other reason than if it were good, it would get its own movie. The same is true in “The Last Metro,” in which the only reason to watch the crew performing “The Vanished Woman” is to detect the parallels to Marion’s own indecisiveness. Lucas informs Marion, “It shouldn’t be played like a duel, but like a conspiracy.” The audience, the end user of this extraordinary effort to put on a show, is ignored by Truffaut. Just clap when needed.

Truffaut paints a beautiful opening, rolling credits against a red backdrop and Lucienne Delyle’s “Mon amant de Saint-Jean.” But he abruptly decides to explain the details of the occupation in a newsreel type of effect, either 1) to help out anyone who isn’t aware of this period of history or 2) to avoid having to depict too many unsettling swastikas during the rest of the movie. We see a map of 1942 France, Nazi flags, descriptions of curfew and food shortages and lack of heat and how Parisians flocked to theaters as an escape, for keeping warm, outside and in.

Perhaps because of its triumphant premise or perhaps because of Deneuve, “The Last Metro” was actually one of Truffaut’s biggest hits. It grossed $3 million in the U.S., a healthy total for a foreign drama, but it was a juggernaut in France, which rewarded it with 10 César awards, a massive sweep including honors for Deneuve, Depardieu, Truffaut and Néstor Almendros.

Gary Arnold of the Washington Post, in his 1981 review, predicted the only film that could “pose a threat” to “Metro” winning the foreign-language Oscar would be “Kagemusha.” Instead, both lost to “Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears” in an upset. The latter was not offered in theaters; Oscar voters had to see it at an Academy screening, a dubious strategy that according to Roger Ebert worked for the 1994 Russian winner “Burnt by the Sun.”

In the Oscar category, Bennent actually one-ups his prestigious “Metro” co-stars. Bennent appeared a year earlier in the West German film “The Tin Drum.” More importantly, his son David landed at age 11 the starring role in that film as perhaps the most obnoxious child portrayal ever. Because of that or in spite of that, “The Tin Drum” won the Academy Award for foreign-language film.

Truffaut idolized Hitchcock and surely appreciated the master’s theory that a bomb exploding in a movie is no special consequence, but a ticking bomb under a table is suspense. As long as Lucas is in that basement, we can watch another act.

3 stars

(January 2019)

“The Last Metro” (1980)

Starring Catherine Deneuve

as Marion Steiner ♦

Gérard Depardieu

as Bernard Granger ♦

Jean Poiret

as Jean-Loup Cottins ♦

Andréa Ferréol

as Arlette Guillaume ♦

Paulette Dubost

as Germaine Fabre ♦

Jean-Louis Richard

as Daxiat ♦

Maurice Risch

as Raymond Boursier ♦

Sabine Haudepin

as Nadine Marsac ♦

Heinz Bennent

as Lucas Steiner ♦

Christian Baltauss

as Bernard’s Replacement ♦

Pierre Belot

as Desk Clerk ♦

René Dupré

as Valentin ♦

Aude Loring ♦

Alain Tasma

as Marc ♦

Rose Thierry

as Jacquot’s Mother / Concierge ♦

Jacob Weizbluth

as Rosen ♦

Jean-Pierre Klein

as Christian Leglise ♦

Rénata Flores

as Greta Borg ♦

Marcel Berbert

as Merlin ♦

Hénia Ziv

as Yvonne the Chambermaid ♦

Laszlo Szabo

as Lieutnant Bergen ♦

Martine Simonet

as Martine, the thief ♦

Jean-José Richer

as Rene Bernardini ♦

Jessica Zucman

as Rosette Goldstern ♦

Richard Bohringer

as Gestapo Officer ♦

Le petit Franck Pasquier

as Jacquôt

Directed by: François Truffaut

Written by: François Truffaut

Written by: Suzanne Schiffman

Written by: Jean-Claude Grumberg

Music: Georges Delerue

Cinematography: Néstor Almendros

Editing: Martine Barraqué

Production design: Jean-Pierre Kohut-Svelko

Costumes: Lisele Roos

Makeup and hair: Jean-Pierre Berroyer, Didier Lavergne, Nadine Leroy, Françoise Ben Soussan, Thi Loan N’Guyen

Unit manager: Jean-Louis Godfroy

Production manager: Jean-José Richer