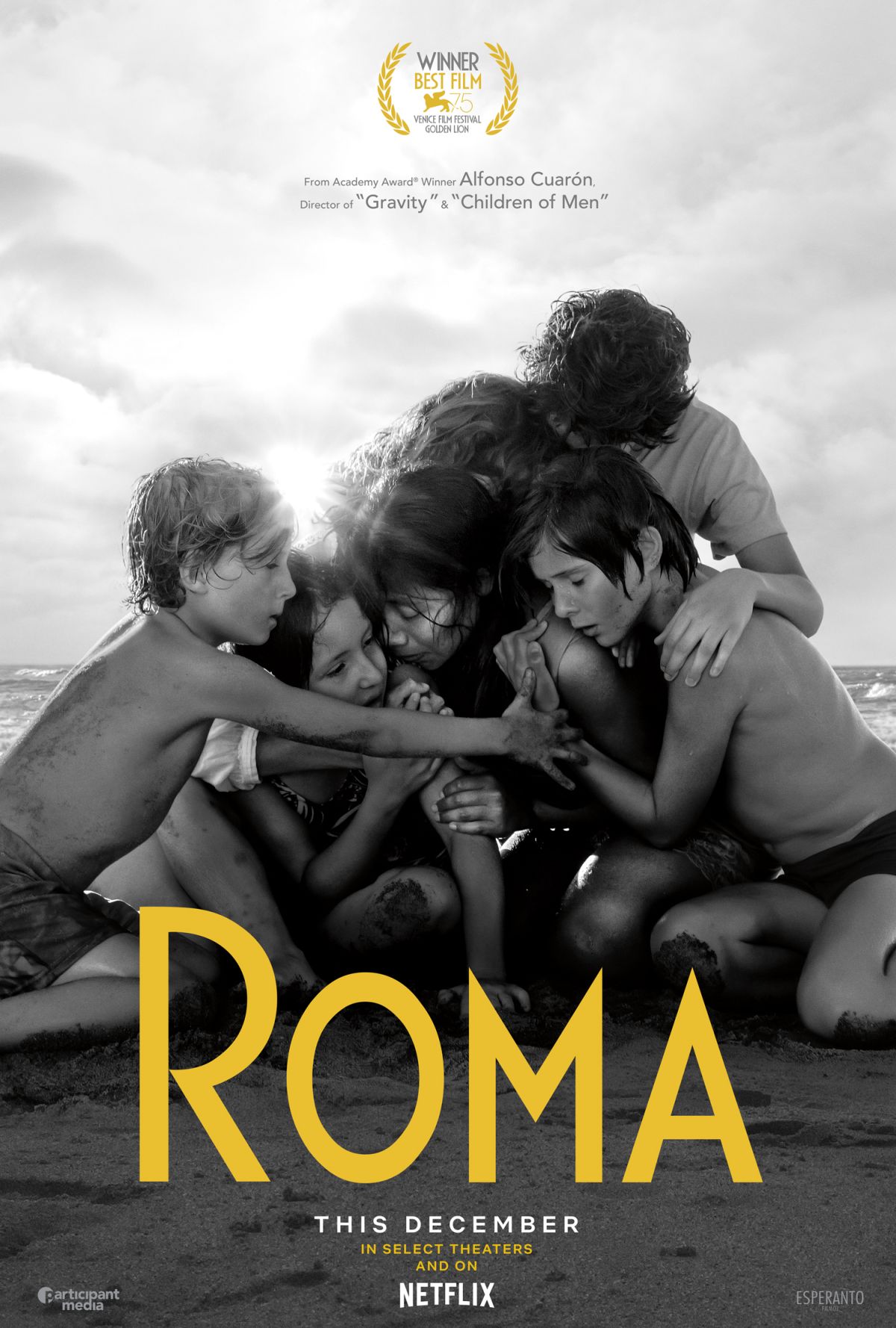

Gripping but draining, seeing ‘Roma’ might require some help

Whether feature films constitute “art” or “entertainment” is an endless debate. When a director in the 2000s opts for black and white photography, it’s clear which definition he prefers.

Alfonso Cuarón’s “Roma” tells parallel stories of two women, of vastly different socio-economic backgrounds, each being let down by a man. It has us know, as did “Ordinary People,” that no amount of money or status can buy insulation from heartbreak, that the things that make us human are universal and not subject to privilege.

“Roma,” like many serious films of the ’60s and ’70s, surely re-ignites questions of capitalism and Marxism in a country that has wavered somewhere between its powerful neighbor to the north and the mercurial governments of the Caribbean and Central and South America. The wealthy employers here are decadent elites. They can’t drive a car 10 feet without hitting a wall. Whatever work is done by the elites is not shown, whereas all of the work done by their staff ... cleaning up dog poop to rescuing children ... is seen. The employers rely on their housekeeping staff not just for the basics, but seemingly ... everything.

Notice, though, the love. Everybody in this home hugs each other about every five minutes. There is 100% unanimity in the acceptance of roles. Cleo and Adela are as much a part of the family as Alice in “The Brady Bunch.” (Actually, have you ever seen a movie or sitcom in which the household help was openly hostile? Maybe “Giant,” depending on the definition of Jett Rink’s profession, or “The Jeffersons,” although Florence, like Jett, had one key backer.) There is virtually no hint that national tensions, which bear a faint resemblance to the crackdown in “Z,” are going to encroach on this particular family. Senor Antonio and Senora Sofia supply the income; Cleo and Adela supply the support. It’s a win-win.

The family is said to be middle class. That they have two housekeepers and a strange indoor driveway suggests they are wealthy, until you see their underwear hanging on clotheslines on the roof of their home.

“Roma,” is semi-autobiographical. That should be a red flag. When filmmakers decide someone else’s story is worth a movie, that is one thing. When they opt for their own, they should probably seek a second opinion. Yet Cuarón gave himself the duties of writer, director, cinematographer, editor and producer, not much different from Cameron Crowe’s uninspiring “Almost Famous.” According to San Francisco critic Mick LaSalle, in a 3-star review, Cuarón was adamant about finding a home resembling his own with the same furniture, “obsessed with details that can’t possibly matter to anyone but himself.”

Cuarón says, “I was a white, middle-class, Mexican kid living in this bubble.” If nothing else, his story is oddly “gringo.” The family and its housekeeping staff look as though they could easily be in Manhattan. The family looks almost as out of place in Mexico City as Robert Mitchum and Jane Greer in “Out of the Past.” The kids don’t even talk about Mexican sports but America’s Super Bowl V, with a curious commentary about Baltimore and Dallas. (Baltimore won the game, by the way.)

But “Roma” will be remembered not for its stories but technique. A century ago, filmmakers used black and white because color was simply too expensive. Nowadays, when someone uses black and white, what does it mean? Think of movies from well past the explosion of color that have opted for black and white ... “Schindler’s List,” “The Last Picture Show,” “Raging Bull,” “Lenny,” “JFK” ... what are they trying to say? Probably that something is bleak, that these characters are scraping to get by, that nobody is living high on the hog, that there might be a dubious element to what we’re watching.

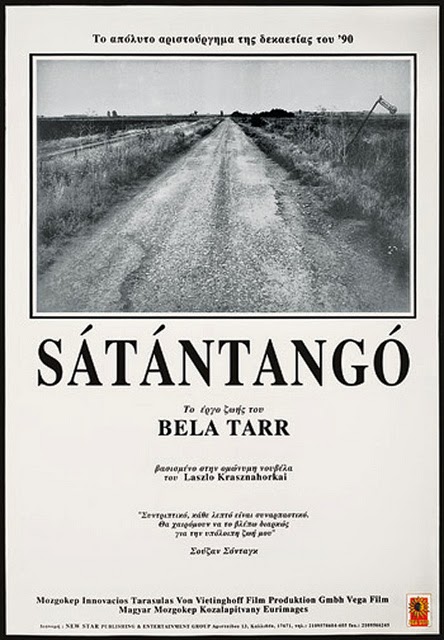

Black and white is beautiful, but so is color. Mexico so often is portrayed as a vibrant, colorful land, while black and white seems better suited to bureaucratic failure of “Sátántangó.” Subtracting color is not only a box-office risk; it severely restricts what a filmmaker can convey. Cuarón tries to make up for that with a widescreen experience that fills in the edges of our peripheral vision with some kind of activity. “Roma” is the type of movie that, decades ago, Roger Ebert would warn of being destroyed by the cropping to 4:3 dimensions for standard television viewing.

But whether Cuarón is asking too much is a fair question. In a theater, the sounds of “Roma” come from all angles. People are heard talking while not shown on the screen. Every few minutes, rambunctious children are underfoot, tussling with each other, making noise. Once, when Cleo and Adela wake the children, are the youngsters quiet. Once. Not one of them is as obnoxious as the boy in 1979’s “The Tin Drum,” but collectively, they are a handful, and not just for their caregivers. For viewers who don’t speak Spanish, the subtitles are yet another distraction. Sometimes, expecting an audience to appreciate the totality of filmmaking excellence, however deep it runs, is a tall order.

The home, though with multiple floors, draws parallels to the strange design of the house in “A Woman Under the Influence,” in which the family’s admirable belief in togetherness unfortunately seems to grant no one necessary privacy. In “Roma,” we can see into everyone’s privacy at the same time. It’s all too easy for children to hear something they probably shouldn’t.

The state of the world around our characters is depicted in a way that can only be described as flimsy. Cuarón does produce a sensational shot of furniture shoppers looking down through windows to the streets, where student protesters are being chased and hunted down. But the impact of this element on the characters’ lives feels so much like the blacklist scenes in “The Way We Were,” which Sydney Pollack admitted was the equivalent of asking people who lived near Auschwitz what Auschwitz was like.

To get the camera outside of the admittedly unique living space, Cuarón tracks his characters to a forest, where a curious fire burns (prompting a community reaction like something out of “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” or perhaps Bondarchuk’s “War and Peace.”), and he will have them walk through mud, an infatuation of Béla Tarr’s “Sátántangó.” No movie since 2012’s “The Queen of Versailles” has been this fascinated by dog poop. And, the boundary between viewers and full male nudity gets demolished here, and something just feels painful about the scene.

While we can observe that Cleo’s trauma is exacerbated by the unwind of her employers’ marriage, Cuarón unfortunately is too reliant on telling rather than showing. We haven’t seen enough of Sra. Sofia and Sr. Antonio to feel anything but a passing interest for their plight. It would have to be assumed that the disintegration of the family would be bad news for Cleo, that there can’t be enough money here for split household. But then again, no. They need each other too much.

3 stars

(December 2018)

“Roma” (2018)

Starring

Yalitza Aparicio

as Cleo

♦

Marina de Tavira

as Sra. Sofía

♦

Diego Cortina Autrey

as Toño

♦

Carlos Peralta

as Paco

♦

Marco Graf

as Pepe

♦

Daniela Demesa

as Sofi

♦

Nancy García García

as Adela

♦ Verónica García

as Sra. Teresa

♦

Andy Cortés

as Ignacio

♦ Fernando Grediaga

as Sr. Antonio

♦

Jorge Antonio Guerrero

as Fermín

♦

José Manuel Guerrero Mendoza

as Ramón

♦ Latin Lover

as Profesor Zovek

♦

Zarela Lizbeth Chinolla Arellano

as Dra. Velez

♦ José Luis López Gómez

as Pediatra

♦ Edwin Mendoza Ramírez

as Médico Residente

♦ Clementina Guadarrama

as Benita

♦ Enoc Leaño

as Político

♦ Nicolás Peréz Taylor Félix

as Beto Pardo

♦ Kjartan Halvorsen

as Ove Larsen

♦ Felix Gomez as Transeunte

Directed by: Alfonso Cuarón

Written by: Alfonso Cuarón

Producer: Alfonso Cuarón

Producer: Gabriela Rodriguez

Producer: Nicolás Celis

Executive producer: Jonathan King

Executive producer: David Linde

Executive producer: Jeff Skoll

Associate producer: Carlos A. Morales

Associate producer: Alice Scandellari Burr

Associate producer: Sandino Saravia Vinay

Cinematography: Alfonso Cuarón

Editing: Alfonso Cuarón, Adam Gough

Casting: Luis Rosales

Production design: Eugenio Caballero

Art direction: Carlos Benassini, Oscar Tello

Set decoration: Barbara Enriquez

Costumes: Anna Terrazas

Makeup and hair: Atenea Téllez, Itzel Badillo, Emma Canchola, Antonio Garfias, Beatriz Vera

Unit manager: Abel Cruz

Stunts: Gerardo Moreno, Tomás Guzmán, Odín Ayala, Omar Ayala, Erick Delgadillo, Marco Ivan Guerra, Michel Guerra, Victor Hugo Martinez, Isidro Mora, Natalia Moreno, Valentina Moreno, Mr. Leo, Iker Perez, Erick Valderrama, Rafael Valdez, César René Vigné