Mikey Madison should’ve

demanded a ‘Pretty’-er

outcome for ‘Anora’

One of the most depressing jobs in the world must be the bureaucrat(s) who has to undo Vegas marriages. In “Anora,” the job is so entertaining, people even are handed fur coats.

“Anora” shouldn’t be taken literally. In real life, someone in Ani’s situation would be hounded by the likes of the New York Post and others so quickly, the bad guys wouldn’t even be able to get to her. That its cinéma vérité approach fails, at times, doesn’t make it any less entertaining. At times, it’s laugh-out-loud funny.

Road-trip movies are common. Adventure movies are rarer. “Anora” qualifies as the latter. Its extensive chase is bogged down by repetition and a bit too many bureaucratic reaches that need to be explained in speeches and an immense deadline that doesn’t really seem like it needs to be a deadline. And yes, it relies on the cellphone. Probably many viewers upon reaching the ending of “Anora” thought they should’ve seen it coming, but it’s a credit to writer-director Sean Baker’s imagination that the villain(s) may not be who we think.

Mikey Madison, surely catapulted to It Girl by this movie, is the prize. She somehow goes underused by Baker. She is so cute, we want to see her doing everything — entertaining clients, slinging the b.s. with her boss, bickering with her rivals, scrapping with the thugs. She’s often doing these things in underwear or stripper gear, sometimes unclothed. For the first half of the movie, Baker leans into all of that. Then he curiously confines her to an SUV and basically assures us that she won’t be harmed, and we start to care less and less about Ani’s story, as she backpedals and concedes.

It’s understood that the filmmakers wouldn’t be publicly noting the flaws or lesser moments of the movie. But in interviews promoting the film, Madison struggles to articulate why much of the film clicks. That’s not unusual, most actors dislike interviews (because, in general, most of the questions are dumb, although that’s not necessarily the fault of the person asking them). She tells a Toronto radio host that Ani is vulnerable on the inside but feisty in every sense on the outside. She talks multiple times of doing her “due diligence” in observing the stripper lifestyle. That’s a job for lawyers, not actors. Roger Ebert would say that accuracy is no excuse for cinema; effectiveness is. She rightly gives credit to Baker — but too much.

Madison is reportedly 25. Were she a more experienced star, she might’ve asserted herself, to the success of all involved. “Sean, you can’t have her overwhelmed by these goons. She’s a fighter, she’s a pro at this racket — she’s getting far more than $10,000 out of this.” John Travolta famously made “Saturday Night Fever” better through force of will. Sometimes, outspoken actors annoy directors. Other times, they make a decent movie a lot better. As much from their opinion as their acting.

Baker’s script makes a critical judgment that eventually works against it. As the problem arrives for Ani and Vanya, she is determined to run. Through a Keystone Kops type of enforcement effort, she is detained. They can’t hold her forever. It must dawn on her that the bad guys — whom she perceives as the bad guys — require her presence to achieve their nightmarish goal, and that fleeing only enhances her leverage. Flagging down a cop would give her the upper hand but wipe out our story. Baker seems to be telling us that this tough cookie is not seeking that leverage because the bad guys have succeeded at breaking her heart.

The third act requires a critical trade-off from viewers — does watching Madison outweigh having to put up with her enormously spoiled 21-year-old beau, who is played by Mark Eydelshteyn, who at times resembles the wide-eyed expressions of Cillian Murphy. Vanya could have his own movie — What a 21-year-old with unlimited money, zero ambition and zero inhibition can do. It would be awful to watch. But it may have a point to make. We are tempted to think, as Ani does, that he actually has a heart. Once the hangover wears off, might that actually be true?

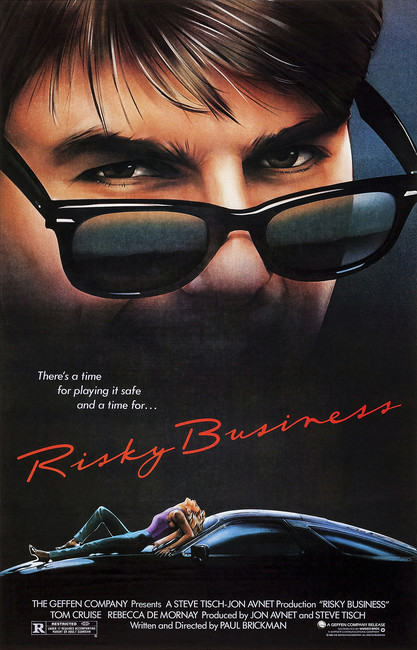

Prostitution is perhaps the most common fascination of the great directors. Tones can vary from horror to comedy. It’s a blatant subject in “Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles,” most recently the No. 1 movie of all time in the Sight & Sound poll, and in famous works such as Godard’s “Vivre sa vie” and “2 or 3 Things I Know About Her,” Bunuel’s “Belle de Jour,” and American films such as “Taxi Driver,” “Risky Business,” “Pretty Woman,” and “American Gigolo.” In many of these, the audience’s interest is the same as the clients’, to get the “real thing” from the person whose job it is to please.

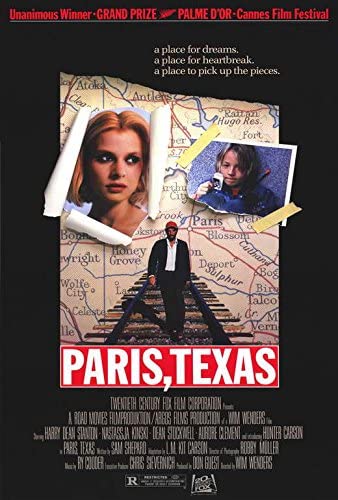

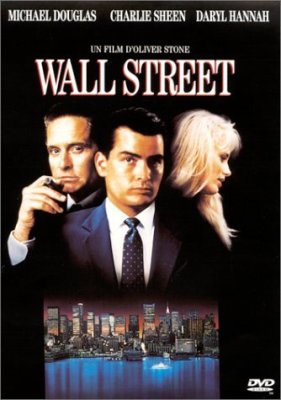

In other films, the concept is not about cash. And the deal, if there is one, is more subtle, something of great interest of directors. In “Wall Street,” there is Darien; in “Paris, Texas,” there is Jane. Hitchcock put forth questionable relationships in “Notorious” and “North by Northwest.” In “Anora,” we see early on that while officially there may be a line between exotic dancing and prostitution, the movie sees little distinction, only a higher-priced tier of service, and Ani is happy not to observe it, and Vanya’s home is surely not the first she has visited away from the office. If there is a mutual relationship to occur here, Vanya has work to do.

While “Anora” could be called the “Pretty Woman” reality check, it is more in the mold of movies such as “The Prince of Tides” and “Leaving Las Vegas” in which professionals think they may have found their soulmate in the form of a client and let their guard down to find out. “Anora” is all about youthful indiscretion but not nearly as comfortable with the impact of money. Or alcohol/drugs. Would Ani really find this gentleman so appealing if he wasn’t sitting on pyramids of cash? It’s left to Vanya to make the questionable determination that they would have a good time even without the money.

Fellow 2024 film “Kinds of Kindness,” by Yorgos Lanthimos, speculates on how human beings may control each other. Money seems the most likely way, but it’s not the only button to be pushed. Vanya and his handlers know that if his parents are displeased, it’s not just the money that could dry up — it’s their stature in Russia and the Russian-American community. Vanya, it seems, has made the same deal over and over again; he can be as spoiled as possible provided he eventually does their bidding.

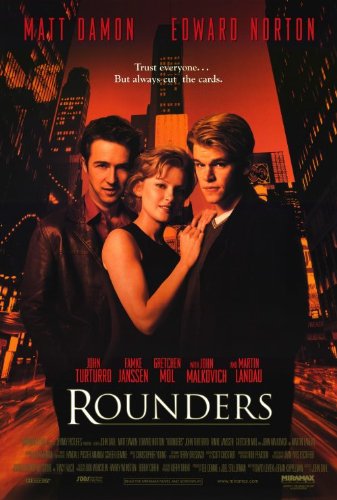

The term “oligarch” is almost exclusively associated with Russia, implying a small number of barons allowed to control sprawling industries by paying fealty to the ruler. Russians are also prominent in another New York City film, “Rounders,” although in that movie they are running the illegal/dubious (although seemingly not dangerous) business activities with principle, whereas in “Anora,” they’re simply the customers. “Anora” will suggest that the Russians are cold and ruthless but bumbling like Boris and Natasha in the Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoons, and the movie seems not to be passing any judgment on the Ukraine conflict.

Will viewers of “Anora” deem exotic dancing an exciting line of work? Baker’s characters may be sexy, but the movie isn’t. His weightiest scenes occur in the dressing rooms and apartments. Like many directors, he likes the lighting provided by strip clubs; you’ll see in the trailers and publicity photos electric images of Madison as the strobe lights flash across her body and her colleagues’.

As New York movies go, “Anora” has visuals in common with “Rounders” in that elites with nice homes tend to find themselves dwelling in the underground. Baker also, like many directors, likes the diner, although no important conversations happen at diners in this film, just tedious interruptions in which people are asked if they’ve seen someone whose picture is on a cellphone. Baker is less inspired in the SUV and plane and in Vegas, but he liberally uses mirrors wherever he goes. Richard Brody thinks there is something not quite connecting on the ground: “The characters move within even the grittiest spaces as if walking past backdrops or C.G.I. green screens.”

Baker’s most vivid location is that of Vanya’s home. Baker says in a video for Vanity Fair that he found the location by Googling and that the family in residence allowed him to film there for three weeks. In the film, the property seems so Russian. Austere angles, hired help everywhere, not a sense of warmth. Ani, like Willem Dafoe in the unfortunately bad 2023 movie “Inside,” is wowed by the opulence, only to find herself suddenly a desperate prisoner smashing luxurious fixtures in hopes of getting out on her own terms.

San Francisco critic Mick LaSalle writes that Madison never lets slip that she is “smarter than the character.” That indeed is impressive, as Ani’s shortcomings unfold. She is admirably fierce, relentless and able to deal with all types of people. The problem is, she cannot analyze any situation beyond surface level and so will perpetually be selling herself short, depressingly when given face time with Vanya’s parents.

Roger Ebert would occasionally mention the Reliable Observer, the character(s) in movies whose observations are believed. In “Anora,” the reliable observers are generally the baddies, both at Ani’s club and in Vanya’s world. They all have seen this kind of movie before, and they know how it turns out, and they are only too happy to try to tell Ani in hopes of speeding the cleanup.

Pressure cookers are a great approach for movies, especially when they don’t involve the tired but often-effective possibility of someone dying. In “Wall Street,” we see the traders scrambling to wrap a deal before the 4 p.m. close. In “Rounders,” we see characters desperately trying to raise enough money in time to avoid a maiming. Deadlines though can be less than visual. One of the shortcomings of “Anora” is that characters are telling us that a certain procedure must be voided by the legal system, RIGHT NOW, even though it’s a mystery how such voiding would remove the family from tabloid headlines anytime soon. The movie blitzes through a couple of bureaucratic quagmires that would never happen under this kind of duress; they take place even more quickly than the disappointing ending in “House of Sand and Fog.”

A more realistic scenario would be the bad guys sitting around at Vanya’s home, watching TV, calling third, fourth and fifth parties to visit the places he tends to go and hauling him in when he has passed out. Baker spends a lot of time having characters smack each other around; one of them (who tends to interrupt the more interesting scenes and whose role in this operation is never really clear) complains forever about his nose. Baker indulges a lot in typical crime-lord-movie tropes. For these types of movies to work, the bad guys have to be basically invincible, full energy for 24+ hours straight, nobody they encounter could actually beat them up or would report them to authorities, and police are somehow oblivious to the reckless driving and everything that’s being smashed.

“Anora” finds itself among a host of otherwise unrelated films, such as “10” or “The Electric Horseman,” in which two people, fortunately/unfortunately, may be meant for each other for a moment, but not for all time. The audience’s magnificent payoff in “Pretty Woman” is getting that Cinderella outcome it’s dying to see for Julia Roberts. There is a strong, but less powerful, payoff waiting for us at the end of “Anora,” except that, a couple of days later, Ani will be right back at the club, no worse for wear.

3.5 stars

(November 2024)

“Anora” (2024)

Starring

Mikey Madison as Ani ♦

Paul Weissman as Nick ♦

Lindsey Normington as Diamond ♦

Emily Weider as Nikki ♦

Luna Sofia Miranda as Lulu ♦

Vincent Radwinsky as Jimmy ♦

Brittney Rodriguez as Dawn ♦

Sophia Carnabuci as Jenny ♦

Mark Eydelshteyn as Ivan ♦

Anton Bitter as Tom ♦

Ella Rubin as Vera ♦

Ross Brodar as Mansion Day Guard ♦

Zoë Vnak as Rachel ♦

Vlad Mamai as Aleks ♦

Maria Tichinskaya as Dasha ♦

Ivy Wolk as Crystal ♦

Karren Karagulian as Toros ♦

Vache Tovmasyan as Garnick ♦

Morgan Charlton as Sunny ♦

Nazar Khamis as Vlad ♦

Charles Jang as Vegas Hotel Manager ♦

Lana Svidonovich as Toros’ Wife ♦

Yura Borisov as Igor ♦

Masha Zhak as Tatiana’s Hostess ♦

Sebastian Conelli as Tow Truck Driver ♦

Irina Finogeeva as Bartender ♦

Mariana Orozco Arango as Pearl ♦

Artyom Trubnikov as Michael Sharnov ♦

Michael Sergio as Judge ♦

Charlton Lamar as Court Guard ♦

Darya Ekamasova as Galina Zakharov ♦

Aleksey Serebryakov as Nikolai Zakharov ♦

Mickey O’Hagan as Divorce Center Clerk

Directed by: Sean Baker

Written by: Sean Baker

Producer: Sean Baker

Producer: Samantha Quan

Producer: Alex Coco

Co-producer: Elizabeth Siegal

Line producer: Olivia Kavanaugh

Executive producer: Glen Basner

Executive producer: Alison Cohen

Executive producer: Ken Meyer

Executive producer: Clay Pecorin

Executive producer: Milan Popelka

Cinematography: Drew Daniels

Editing: Sean Baker

Production design: Stephen Phelps

Art direction: Ryan Scott Fitzgerald

Set decoration: Christopher Phelps

Costumes: Jocelyn Pierce

Makeup and hair: Justine Sierakowski, Annie Johnson, Callie Filion

Stunts: Acei Martin

Thanks to: Ulia Petrova

Thanks: Roger Harkavy

Special thanks: Kurt Leitner, Dasha Timbush