‘The Birds’ is not the mother of all Hitchcock thrillers (but it’s hard to imagine a crazier first date)

We live in our fears. We’re not supposed to. We can’t help it. The world is an enormously complicated, fragile place. There’s too much that can go wrong. The car could break down. We could lose our job. It might rain during our outdoor wedding. Someone we love may be ill. Someone we love may not love us back. The high winds may spawn a tornado. The neighborhood we’re passing through may be sketchy. Other countries may give us trouble.

Alfred Hitchcock’s got one you didn’t think of — birds might attack us.

“The Birds” is a cop-out, an incomplete film. It’s so good at the one thing it does, it doesn’t want to do anything else. There is no Act III. It has fans. It ranked 189 on the most recent Sight and Sound poll. San Francisco critic Mick LaSalle writes in May 2024 that “The Birds” is “a powerful dramatization of how civilizations start to crumble in the face of a massive threat.” Pauline Kael, on the other hand, in 1964 explained it as “terrible.”

There are various interpretations of what “The Birds” may represent, but it is probably, like classics such as “Last Year at Marienbad” and “Persona,” much more filmmaking than message.

It has faint parallels to “Psycho,” of a woman setting out on an adventure running into seemingly unrelated horror that includes a man and his mother. Unlike in “Psycho,” the original drama lingers. The movie is a contrast of two problems, one of them being immediate physical danger, in which people rally to help each other, and the other being long-term psychological warfare that we wage on each other and sometimes ourselves, as people size up potential lifelong alliances, only to temporarily set those concerns aside.

Cinema decided long ago that children are fair game, even in movies that may be considered disturbing. Still, there’s a boundary that’s crossed in “The Birds.” Children are attacked twice, in places considered safe (school and a birthday party), and run around screaming while seeing adults killed. It is a similar effect of the hijacked school bus in “Dirty Harry” — that we’re dealing with some of the worst kind of evil here. Sometimes in critiquing horror movies, Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel would note that it’s fun to be scared, that’s why people watch the movies. Sometimes, it’s not so much fun.

Eventually, “The Birds” will play out like some horror films (“Invasion of the Body Snatchers” and “Race with the Devil” are good examples), where extraordinary, possibly successful efforts to fight off the evil are eventually overwhelmed by sheer numbers. Before that happens, the four or five people within this complex relationship will end up trapped together in rooms, setting aside doubts for the sake of survival.

“Tippi” Hedren (she is billed with quote marks around her first name and in ads received the “introducing” tag) is one of the most remarkable Hollywood success stories. She was discovered by Hitchcock from commercials. This process irked Pauline Kael, who complained in one of her final interviews that Hitchcock “had often cast people not after seeing them in pictures but from seeing them on a reel of film their agents brought.” Hedren signed a contract with him and quickly appeared in two famous films, never appeared again in something of that stature, but she kept working, and then watched first her daughter and then granddaughter go on to successively bigger careers. Her significance as Hollywood matriarch is considerable, but so is her significance as perhaps Hitchcock’s last ... “muse” doesn’t seem like the right word, maybe the last of the Hitchcock archetype. He still had a few more films to go, but the combination of “The Birds” and “Marnie” marked the end of a magnificent era.

Hedren is not tasked with a dual character like Kim Novak in “Vertigo,” nor does she have to pull off the does-she-mean-it-or-doesn’t-she secret agent routine of Eva Marie Saint in “North by Northwest.” Skeptics may say her role as Melanie in “The Birds” is more about screaming than method acting. In 2012, Hedren indicated Hitchcock was most interested in the former and came up with an excuse to batter her, for five days, with live birds in the house rather than mechanical ones. “I was just overwhelmed and in some form of shock, and I just kept saying to myself over and over again, ‘I won’t let him break me. I won’t let him break me.’ ” She has given other statements suggesting her biggest complaint about Hitchcock was harassment during the “Marnie” shooting. In “The Birds,” the non-action acting for Hedren was mostly about protesting to a man that she’s not as bad as her reputation (which both characters recite) may seem. “The Birds” is burdened by the same problems as in “Vertigo,” there’s not enough to show, so characters spend a lot of time reading the backstory to viewers. The body of one prominent character, but not her death, is shown; curiously it’s left to a crying child to explain how she died.

“The Birds” was Hitchcock’s first film after his incomparable three-year span of “Vertigo,” “North by Northwest” and “Psycho.” “The Birds” was based on the novella by Daphne du Maurier, published in 1952, about bird attacks in Britain. Hitchcock clearly realized that du Maurier’s work would be a visual spectacle. There are many ways he could insert his human characters into this ordeal; he happens to go about it rather clumsily. A meet cute involves two people confusingly pranking each other, and one of them makes a decision to assemble intel and bear a (sort of) secretive gift within a day or two. It sure could be a lot simpler — say, she’s not sure she likes him, but he left his wallet at the shop, and she decides to return it.

Too often, characters are sitting in rooms, having backstory conversations about all kinds of subjects that occurred long ago offscreen. As in “Vertigo,” characters will spend a lot of time riding in cars, even when under heavy attack. It’s the old-fashioned way of riding in cars that Hitchcock was still using in 1963, not the furious adrenaline of “Bullitt” just a few years later.

For his attackers, Hitchcock could use spiders, snakes, killer bees — many horror movies have done so. Birds are an interesting choice. They are very mainstream. Beautiful creatures. Reviewer Bosley Crowther of the New York Times writes that birds are “one of nature’s most innocent creatures and one of man’s most melodious friends.” Yet they are not saints. They will attack each others’ nests. They will squawk at people when people get too close. Still, they are a pleasant part of everyday life, staying almost completely out of humans’ way. The notion of them turning on us, and what that could mean ... it’s kind of scary.

Another interesting choice is San Francisco, or nearby Bodega Bay. “Vertigo” was a San Francisco film. Perhaps he sensed something mysterious about the Bay Area as some kind of haunted outpost of the continental United States. Hitchcock made his characters more upscale than the people in du Maurier’s book — not a surprise, given that Hitchcock movies are about people in suits.

Hitchcock in “The Birds” sort of paints himself into a sci-fi or horror-movie corner. The characters are not going anywhere or attempting to do anything when evil arrives. So the outcome hinges on whether they can simply outlast the menace. In some of these films, the heroes must devise a solution (“The Towering Inferno”), but in others, like “The Birds,” and “The War of the Worlds,” the magnitude of the problem is beyond the understanding of the victims, and the strategy becomes, Wait ’til it goes away, hopefully.

Assume for a moment that the birds never actually show up in “The Birds.” We have a woman attracted to a man who seems highly eligible, but she gradually realizes there are unusual barriers to connecting with him. Everyone seems in judgment. Among the curiosities: People in town seem to know a lot about the man’s family but have strange discrepancies about what their names are. The woman will meet the last woman, a brunette named Annie played by Suzanne Pleshette, who had the same idea about the same man, and the blonde will receive a little bit of clarity — but just a little. Then she will meet the man’s mother, who may or may not have final say over whom he socializes with.

Melanie and Annie will form a believable friendship and non-compete agreement, as Annie seems intrigued at enabling the opportunity to determine whether this blonde may succeed where Annie failed. Crowther writes that Annie is “pleasant but vaguely sinister.” Does Annie still live in this town because she hopes for a second chance at Mitch? Or does she simply have nowhere to go from here?

Rod Taylor, as lawyer Mitch Brenner, had a prodigious career but never had the “signature” film that everyone remembers. His credits improbably stretch from “Giant” (a small role) to Quentin Tarantino’s “Inglourious Basterds,” also a small role. He is a much more dashing figure than Claude Rains in “Notorious,” and it seems a stretch to think a mother could be weighing on the social life of a guy who seems to have this much going for him. He is too neutral — he is never really hit by the thunderbolt, and he seems more interested in testing Melanie than actually dating her.

An ad for "The Birds" in the Chicago Tribune, April 7, 1963

One possible interpretation of “The Birds,” perhaps like “Rear Window” or “The Amityville Horror,” is a statement on mass hysteria. For a while, the people reporting attacks are not fully believed. At least, the police do not seem to believe there is anything unusual. Mitch tells the local police officer that “The birds invaded the house.” The officer says it’s “more likely” that the birds just got in and became “panicked.”

Is there some reason humans can’t fight back with weapons, unleash some cats (the squawking of the birds in the movie actually sounds a lot like cats screeching); can’t they just pile into buses and leave the area, is there some reason birds who can claw through solid wood can’t fly through open doors or rip off a convertible top? Is it possible that a couple flocks of birds got agitated, approached people, and a couple people happened to die, and some bystanders became hysterical and assumed they were under attack?

If so, it’s only a half-hearted “Gaslight” approach (a film that’s not directed by Hitchcock but seems like it could’ve been), as neighbors and bystanders do believe it. Children are told to take part in a fire drill, which seems a lot more like the kind of (nuclear) disaster drills that American schoolkids had to do into the 1980s. Perhaps “The Birds” is telling us that government is too skeptical of its citizens and doesn’t rush to their aid as quickly as it should. How much of a threat is it, really, to be surrounded by birds, can’t we just fight them off? No, there’s collateral damage — at one point, a bird attack at a gas station will somehow ignite a vehicle fire like that seen in “North by Northwest.”

What about the Trojan Horse theory. That we’re eager to keep birds in our home, except the wrong ones show up. Is it possible that Melanie and Mitch, and by extension, the community, are being punished for the lovebirds purchase? The attacking birds seem oblivious to the lovebirds and attack other facilities and people as well as Mitch’s mother’s home.

An obvious potential theory, suggested or implied by Mrs. Bundy, a bird expert in a diner who says “ornithology happens to be my avocation,” is that because beautiful creatures such as birds are attacking, humans must have committed some sin against nature, probably encroaching on natural habitat, such as the notion behind “The Amityville Horror.” But other than Mrs. Bundy’s protestations that birds don’t have the brainpower to “launch a mass attack” and never unite with fellow bird species and aren’t aggressive creatures, there’s no suggestion in the movie that human settlers have usurped formerly avian territory or diminished any food source. The birds are sort of like the whale in “Orca,” somehow targeting specific humans.

Look at the state of the world. “The Birds” was filmed in 1962 and released in 1963 (around the same time, coincidentally, as another famous bird-related title, “To Kill a Mockingbird”), just before the dawn of counterculture but light-years from it, as evidenced by “American Graffiti,” whose characters feel a little more connected to pop culture. Shortly before the American consciousness became consumed with Vietnam, there was a Cold War that seemed heavily concentrated on two areas: Berlin, and outer space. Do the birds represent ICBMs, raining down upon us with no defense? Hitchcock clearly found the Nazis to be more intriguing villains than the Soviets.

Hitchcock’s mothers, and their sons ... It’s one of filmdom’s most famous themes. (Hitchcock had other themes, too, such as staircases, espionage, distrust of government operations, and his penchant for appearing in his own films.) (His theme of distrust of government, curiously, was well entrenched by the time of “The Birds,” which was released just before JFK’s tragedy and America’s ramped-up involvement in Vietnam.) Exactly what is he trying to tell us about mothers?

His most famous mother — the mother of Norman Bates — is not even an actual character. The mother-son relationship in that film is depicted, in the mind of the son, as one of extreme jealousy driving the son into murderous madness. In “Notorious,” Leopoldine Konstantin, a famed German actress, plays the domineering mother of Claude Rains who is correctly skeptical of his love interest.

Parental tension is done with daughters too, though it’s not the same, cinematically. “Lady Bird” (which isn’t really about birds) is a recent well-known and well-regarded film about a turbulent mother-daughter relationship. The tones vary. There have been “Terms of Endearment.” And “Steel Magnolias.” And of course, 2023’s “Barbie.”

Roger Ebert used the term Reliable Observer for those characters who tell us the truth about what is happening around the protagonists. Hitchcock’s mothers fulfill that role in sinister or cynical ways. They are perhaps too reliable, creating self-fulfilling prophecies at the expense of observing.

Most movie scripts see mothers as a hindrance. We have no idea whether Rocky Balboa’s mom wants him in the ring. We never see Daniel Kaffee in “A Few Good Men” asking mom if he’s as good as his father. Joe Pendleton in “Heaven Can Wait” dies (sort of), and whoever his parents are is irrelevant, to Joe and the audience. Most film moms who are actually depicted, such as Mama Corleone or Bud Fox’s mother, would realistically have a lot to say but are benign to the plot. In teenager movies such as “Risky Business” or “Dirty Dancing,” moms get a few token scenes, if only because it would seem odd in those movies if they weren’t there. Hitchcock is unique in plunking disapproving mothers into the middle of action plots.

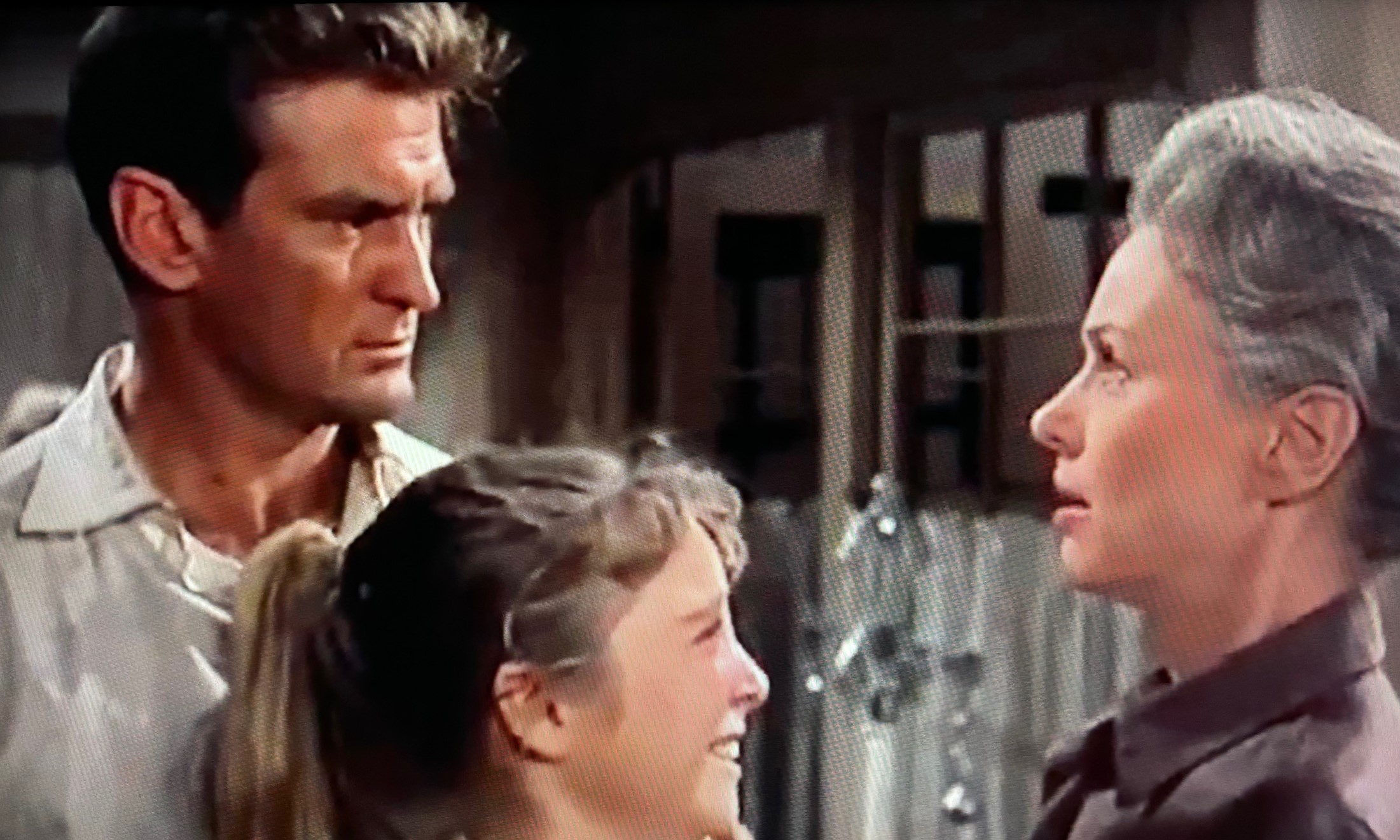

In “The Birds,” Jessica Tandy will provide just enough skepticism to keep her son’s newfound love interest uneasy until a major crisis descends on them. And then her embrace of her son’s embattled love interest will be the most significant shot of the film. Perhaps Hitchcock sees Tandy’s presence, and that of other mothers in his films, as economical. He doesn’t have to invent a tedious conflict to keep Mitch and Melanie apart before disaster strikes, as the scripts are forced to do in “Airport” and “Airport 1975.” Rather, he simply shows mother frowning, and that’s the excuse for why Mitch is a little slow to accept this young beauty who made a long trip to see him.

There is a portrait of Mom’s late husband, Fred, on the wall, and, like the disjointed meet-cute story between Melanie and Mitch, the effect of Fred over this family can’t really be shown and must be recited in speeches. Mom tells Melanie that she found purpose in life in getting up to make breakfast for her husband. She also tells how she envies how Fred interacted with the children, apparently in ways she cannot. “Mitch has his own life,” she adds, ironically.

At one point, Mother will bluntly admit, in tears, why she may intrude on Mitch’s life: “I don’t want to be left alone.” Despite her coldness, Mom does seem willing to give the idea of Melanie as a daughter-in-law a shot, even if that idea needs convincing. “I don’t even know if I like you or not,” she tells Melanie.

There’s an important distinction about the birds in “The Birds,” and it’s not about being different species. It’s the difference between the birds in a cage and the birds in the wild. The birds in the cage are, in the movie’s portrayal, domesticated, docile pets. They are the source of the meet cute and the plot device that brings the potential couple together. They are oblivious to the violence occurring around them and are not attacked. A point is made at the end of the film that those birds have not committed any wrongdoing and can be saved.

Birds remain popular pets. Some people’s views about pet stores have changed since 1963. Were moviegoers troubled then to see these creatures in a covered cage serving as an artistic motif while mayhem surrounds them? In 1963, PETA was a couple of decades away. The organization’s website says there are an estimated 20 million birds in U.S. homes. “There is no such animal as a ‘cage bird.’ All caged birds were either captured or captive-bred,” the organization says.

Pauline Kael apparently didn’t review “The Birds” but did opine in 1964 that “The Birds,” “Irma La Douce” and “55 Days at Peking” were “terrible movies ... in varying degrees pointless and incomprehensible.” Kael might’ve been dismayed when “The Birds” became the most-watched TV movie in history on Jan. 6, 1968. That was a Saturday night. A recent Hitchcock film, while he’s still in his prime, a great source of fascination.

Those were times when movie credits weren’t plastered with assurances that “no animals were harmed in the making of this motion picture.” There were live birds used in this movie, and who knows what happened to them. Perhaps “The Birds” is ironically just a reminder: Be kind to our feathered friends.

3.5 stars

(September 2024)

“The Birds” (1963)

Starring

Rod Taylor as Mitch Brenner ♦

Jessica Tandy as Lydia Brenner ♦

Suzanne Pleshette as Annie Hayworth ♦

‘Tippi’ Hedren as Melanie Daniels ♦

Veronica Cartwright as Cathy Brenner ♦

Ethel Griffies as Mrs. Bundy ♦

Charles McGraw as Sebastian Sholes ♦

Ruth McDevitt as Mrs. MacGruder ♦

Lonny Chapman as Deke Carter ♦

Joe Mantell as Traveling Salesman at Diner’s Bar ♦

Doodles Weaver as Fisherman Helping with Rental Boat ♦

Malcolm Atterbury as Deputy Al Malone ♦

John McGovern as Postal Clerk ♦

Karl Swenson as Drunken Doomsayer in Diner ♦

Richard Deacon as Mitch’s City Neighbor ♦

Elizabeth Wilson as Helen Carter ♦

William Quinn as Sam ♦

Doreen Lang as Hysterical Mother in Diner

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock

Written by: Daphne du Maurier (story)

Written by: Evan Hunter (screenplay)

Cinematography: Robert Burks

Editing: George Tomasini

Production design: Robert Boyle

Set decoration: George Milo

Makeup and hair: Virginia Darcy, Howard Smit

Production manager: Norman Deming