The ‘fabulous’ Allan Carr somehow couldn’t avoid an unhappy ending

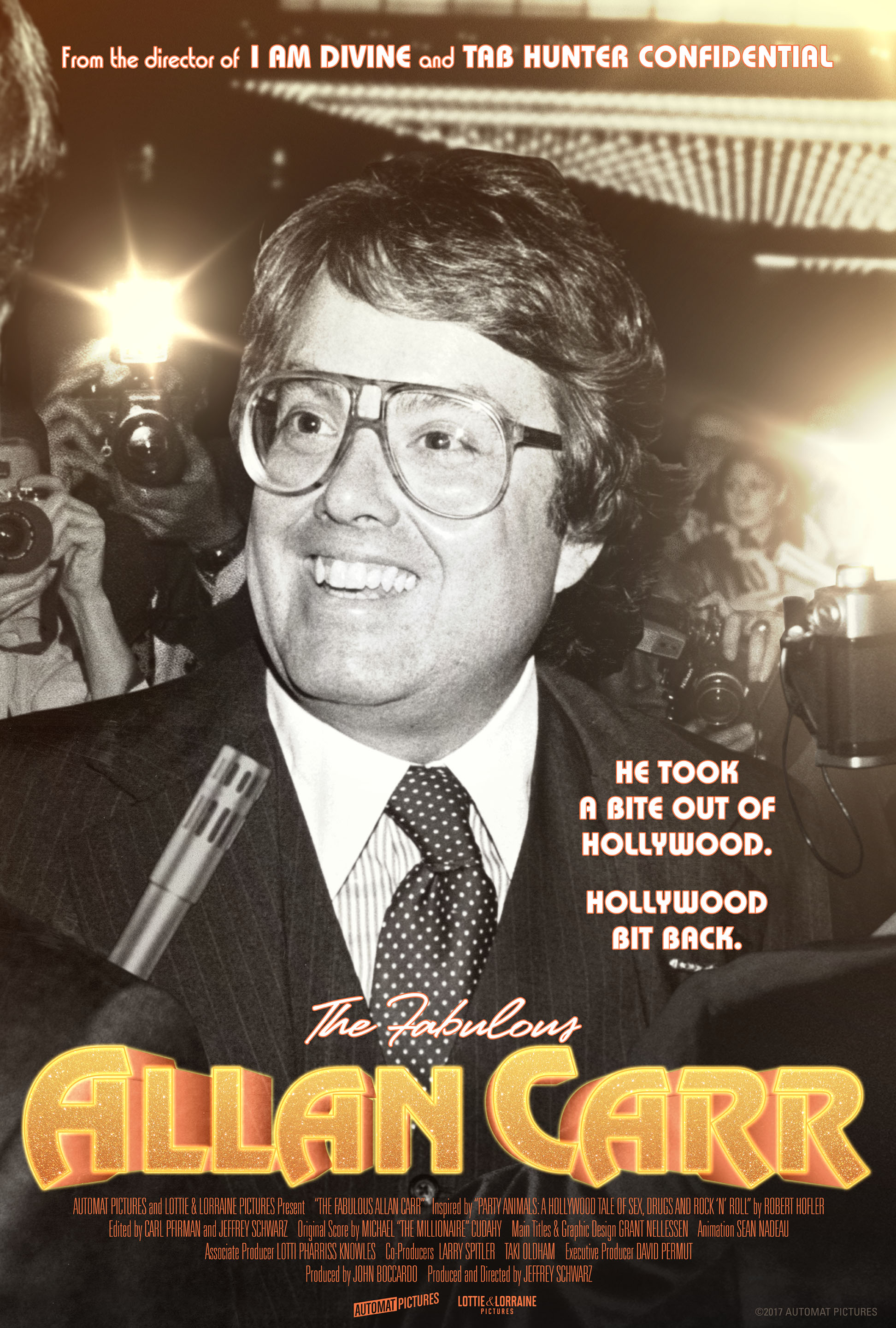

“The Fabulous Allan Carr,” an excellent 2017 production directed by Jeffrey Schwarz, is an intriguing project for at least three reasons: 1) Carr had, according to Schwarz, “such a huge impact on popular culture”; 2) he is not well-known outside of Hollywood, and 3) he is deceased with no surviving family members, allowing close friends and associates to comment freely on his strengths and weaknesses without fear of being cut out of his life or business.

Unfortunately, “Fabulous” falls into a gray area of labeling. It is too much to call it a “documentary,” but it is far more than an “E! True Hollywood Story.” Schwarz’s wide range of interviews (the best are with Bruce Vilanch and Bill Oakes) and impressive array of TV clips, plus some catchy, cartoon illustrations to fill in the visual gaps, carry the 90 minutes that pass all too quickly.

To attract interest and financing, projects such as Schwarz’s need a sales pitch. Sometimes, these pitches don’t tell the real story. The poster for “Fabulous” includes the tagline, “He took a bite out of Hollywood. Hollywood bit back.” But Carr’s disaster with the 1989 Oscars is not at all why he’s a significant figure.

Carr is among the 1 in a million who went to Hollywood with a dream and actually lived it. As Schwarz notes in an interview, few people grow up dreaming of being producers rather than actors. Carr actually achieved more than most movie stars — incredible wealth, an “it” residence, considerable influence ... and an A-caliber guest list.

But that coming-of-age story — how Carr (born Solomon), who is heard saying he’s “half-Jewish and half-Catholic,” left a comfy suburban life in the Chicago area in his 20s with no family connections to Tinseltown — is far less chronicled and less available than his Hollywood exploits, so viewers, presumably along with Schwarz, don’t really know how in the world this fellow got to be Ann-Margret and Roger Smith’s rep or how he somehow got credited as the “discoverer” of Marlo Thomas. (Ann-Margret is the most notable omission among the interviewees; Smith died in 2017, the year “Fabulous” was first shown.)

Carr succeeded simply because he willed it. That’s much harder than it sounds. Most people take life as it comes, responding to ups and downs and the occasional opportunities. Carr had an extraordinarily important trait that few humans have: A determination to make something happen.

On the surface, a Hollywood career seems tough to beat. Underneath, it’s a massively cutthroat business, way oversupplied, all kinds of hangers-on desperate for a break and not above back-stabbing, heavy drug use and drinking (not by all). You might even have to change your name. Carr was comfortable in this environment. Most people aren’t.

Sure, many people say they would love to be movie stars or directors or screenwriters and trek to Southern California. It turns out that cash might be more important than talent. Carr invested his way into show business, “small amounts of money in Broadway shows,” while still a student at Northwestern University, according to one obituary. Another obituary says he “entered the entertainment field through the Playboy television enterprise.”

How much wealth did he grow up with? Carr was an only child. He says in one clip in “Fabulous” that his family was in the “retail furniture business.” Longtime friend Joanne Cimbalo says, “I don’t think he wanted for much.”

However much money Carr got from his parents, he overachieved massively in this department. His is undeniably a self-made story, unlike, say, that of Megan Ellison, who in financial terms clearly hit the ground in Hollywood running.

He may have started with money, but it was Carr’s instinct that really paid off. He not only sensed the permanent appeal of clients such as Ann-Margret, he had a knack for borrowing or adapting someone else’s hit. In the early 1970s, he saw long lines in Mexico for “Supervivientes de los Andes” and brought it to U.S. viewers, with dubbing, in 1976 under the title “Survive!,” a low-budget enterprise that “made him a millionaire,” Vilanch says.

Carr clearly peaked with the film version of “Grease,” a megahit lifted from a highly popular stage production. One book reviewer scoffs that Carr simply “scraped the grit” and that his version of “Grease” was but “a piffle of bogus nostalgia” and just a “sanitized movie version” of the show. It worked humongously, as Schwarz adequately portrays.

Carr is rightly credited with enough success that there’s no need for Schwarz to embellish. The biggest lapse of “Fabulous” involves the fact-checking of Carr’s role in promoting the 1978 Oscar winner “The Deer Hunter,” a long, often-grim but powerful take on the wounds of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

Schwarz interviews Thom Mount, who in his mid-20s was president of Universal Pictures at the time of “The Deer Hunter” (and apparently is long-rumored to be the model for the Tim Robbins character in “The Player.”) Mount says he called Carr and asked for advice in creating buzz.

According to Mount, “He conceived of the first late-in-the-year release for Academy consideration in the history of Hollywood.”

That is ludicrous. According to the book Inside Oscar, amid many other accounts of awards-inspired scheduling chicanery since about the late 1930s, there was 1941’s “How Green Was My Valley,” which “Darryl Zanuck had intentionally opened on the last day of Oscar eligibility in order to keep it fresh in Academy members’ minds.” That movie won best picture too.

Carr in 1978, according to the same book, “instructed Universal to scrap its scheduled fall release date and open ‘The Deer Hunter’ for one week only in December in Los Angeles and New York.“

According to the book, “‘Of course, every performance in New York and L.A. was sold out that week,’ Carr gloated, but he arranged special screenings for Hollywoodites who couldn’t get in.”

An analyst quoted in the book wrote, “The company brought out of mothballs a variation of the reserved-seat playoff pattern by which ’60 blockbusters were sold, and the movie took on an aura of uniqueness which led to key awards."

Faithful to Carr’s career timeline, Schwarz saves the 1989 Oscars as the climax of his production. Schwarz hits a home run here, presenting several opinions on what went wrong with the Snow White number (basically everything) and enough footage of it (presumably the Academy and ABC hold copyrights) for viewers who never saw it or had long forgotten it.

Busts are fun to watch and talk about. Seeing the clips now, the Snow White number seems quirky or thrown together, not awful. Schwarz includes an interview with Eileen Bowman, cast as Snow White; it wouldn’t have hurt to have Rob Lowe too, but that’s a tough get. Schwarz probably could’ve taken it a step further and questioned whether A) criticism of a skit at an awards show is really a big deal at all or B) whether the general public even noticed; the quality of the opening production was not even mentioned in Roger Ebert’s overnight review of the Oscars.

Carr’s flop, in which he combined Snow White, Rob Lowe, “Proud Mary” and dancing tables with what he really cares about, aging stars from Old Hollywood, revealed the hole in his game, which was a starry-eyed fascination with former greats. It would be one thing if he could bring back Bogart, Bergman and Hitchcock rather than a run-of-the-mill batch of retirees, the likes of whom turn up every year. Had Carr been a baseball junkie and put in charge of the 1989 World Series, he probably would’ve tried to get Mantle, Mays and Koufax into the starting lineups.

It seems as though Carr was someone adept at channeling criticism into productivity. Friend Gary Pudney says in “Fabulous” that even in Carr’s heyday, “He was hard to take with a lot of square people. ... People didn’t really have a great respect for Allan.”

So it seems that someone of Carr’s chutzpah should find a way to launch the Oscar carping into bonus publicity. Apparently, after a decade of big misses and health struggles and perhaps poor self-image, Carr had had enough.

“He was a highly volatile personality,” Vilanch says. “Never took an anger-management class. He would push people away. He would do something to get you mad at him so you would leave him alone. You couldn’t get too close to him. He was also afraid that you would know his secret. His secret being that he wasn’t all that he was cracked up to be, in his own mind.”

Lorna Luft, a friend of Carr’s, says he was something of a “cartoon.”

Author Robert Hofler wrote that Carr “glittered in gold and measured less than an inch in depth.” A reviewer of Hofler’s book, Erik Himmelsbach, calls Carr “a boorish, obese man.”

Joanne Cimbalo, a longtime Carr friend (whose LinkedIn profile describes her as a “Licensed Professional Counselor

”), says there was an “undercurrent of unhappiness” about him.

Schwarz has put together more of a timeline than documentary. There is a certain tragedy about Carr, who died at 62 of bone cancer, evidenced by Schwarz’s frequent interview clips: This hugely successful person, living a dream, is not with us now likely because he could not control his weight. Schwarz includes commentary on this subject but doesn’t go near the chicken-and-egg question: Was Carr unhappy because of his weight, or did he eat because he was unhappy?

Rather, Schwarz indicated to an interviewer that he was intrigued by Carr’s story because he wanted to “explore this idea of sort of, gay identity particularly in Hollywood.” But “Fabulous” actually offers no proof of whether being regarded as gay was a plus or minus for Carr. A-listers were friendly with him and attended his parties. The consensus seems to be that if you make money, you’re fine. Nobody, including Pudney, suggests Carr was shunned by anyone for reasons of sexual orientation though clearly on some levels that must have happened. Is it possible such a persona made Carr more in demand in some ways? That is never assessed.

Schwarz’s production is a gallant, comprehensive and highly watchable profile far superior to many bios in recent years of people far more well-known than Allan Carr. It is kind of in that no-man’s land between feature film and streaming gem. Perhaps “Fabulous” could’ve enjoyed a bigger reception had it just been able to consult its subject on marketing.

“Nobody could sell a movie like Allan Carr could sell a movie,” Schwarz says.

4 stars

(December 2019)

“The Fabulous Allan Carr” (2017)

Featuring: Allan Carr

♦

Robert Osborne

♦

Bruce Vilanch

♦

Lorna Luft

♦

Randall Kleiser

♦

Sherry Lansing

♦

Alana Stewart

♦

Paul Rudnick

♦

Marilyn Sokol

♦

Eileen Bowman

♦

Jeanne Wolf

♦

Bill Oakes

♦

Thom Mount

♦

Gary L. Pudney

♦

Joanne Cimbalo

Directed by: Jeffrey Schwarz

Producer: Jeffrey Schwarz

Producer: John Boccardo

Co-producer: Taki Oldham

Co-producer: Larry Spitler

Associate producer: Lotti Pharriss Knowles

Executive producer: David Permut

Music: Michael Cudahy

Cinematography: Jeff Byrd, Matt May, Keith Walker

Editing by: Carl Pfirman, Jeffrey Schwarz

Makeup and hair: Emily Blackmun, Catalina Cacho, Carissa Ferreri, Julianne Kaye Faye Lauren, Galaxy San Juan, Jenni Shaw