However occupied, when two gorgeous women can’t get enough of you, life isn’t so ‘Unbearable’

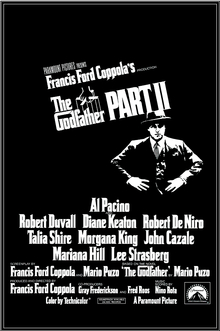

Hats can be powerful movie symbols. Cillian Murphy wore one in “Oppenheimer”; so did Al Pacino in both “Godfather” films.

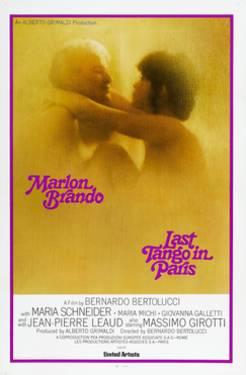

So did Maria Schneider in “Last Tango in Paris,” a movie eagerly compared to “The Unbearable Lightness of Being,” the ambitious 1988 international project that is way too collaborative to match the mood of “Tango” but loves its hat just as much.

“Lightness” is the work of a European all-star team. Actually, not just all-stars, but superstars. It is based on the 1984 novel about Czechoslovakia’s 1968 Prague Spring by Milan Kundera. If you had never heard of the novel, you would still have to think, about 15 minutes into the movie, “This is from a book.” It may look like a book but perhaps didn’t feel like it. According to the book’s Wikipedia page, Kundera added a note to later editions of the Czech book that the movie missed the spirit of the novel and that he would no longer allow adaptations.

“Lightness” is officially an American film, directed by Philip Kaufman, who had impressive credits even before his breakthrough in “The Right Stuff.” His casting in “Lightness” is jaw-dropping and the reason the film resonates: Daniel Day-Lewis and Juliette Binoche, well before they were international stars. Stop right there. “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” co-starred Daniel Day-Lewis and Juliette Binoche before most Americans had ever heard of them.

There were several Ingmar Bergman veterans involved in the film, Lena Olin and Erland Josephson and cinematographer Sven Nykvist, plus another notable Swede, Stellan Skarsgård, who’s associated with Lars von Trier pictures.

Seems impossible to go wrong. Something, though, isn’t quite right. Maybe because this is a Czech story — and sometimes a Swiss story — performed by Americans, Brits, French and Swedes. Punctuated by lovable animals.

“Lightness” is notably produced by Saul Zaentz, who knew Oscar formula as well as anyone. He was behind not only “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” but “Amadeus” and “The English Patient.” The first big decision concerns language. Like “Amadeus,” “Lightness” will be English dialogue, but with characters speaking in accent. This is an acceptable approach for an aspirational film. But it means we are seeing universal themes, not local ones.

A Japanese poster for “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”

And so we get lingerie. With hat. Often with mirrors. These scenes are the most inspired and most elaborate and clearly what must’ve motivated Zaentz and Kaufman to do the film. “The film will be noticed primarily for its eroticism,” writes Roger Ebert. That’s true, but there is one other area of keen interest to Nykvist and Kaufman, which is blending images of the characters into actual footage from 1968 unrest. This was effective for the time but nowadays is too easy and too common. We already know which side they’re on. And it seems the blending is all that they cared about — Day-Lewis and Binoche are seen watching the tension with nothing to do; their appearance in this footage is not even needed.

One of the most famous Czech films is “Closely Watched Trains,” the 1966 foreign language Oscar winner. That movie, black and white and very gray, came just before the events depicted in “Lightness” and was about the previous occupiers, the Nazis. “Lightness” is a (mostly) full-color story of extreme detachment. It implies that marriage and family and business ties are anvils, that hedonism is the escape, that the more involved we get in “heavy” human situations, the more the cycle repeats itself in ways we can’t float away from. This is not so far off from the 2023 movie “Perfect Days,” by Wim Wenders, featuring a man in his 60s who is not into sex but refuses human connections and thrives on a lonely experience with the arts and nature.

To achieve hedonism, it helps to be a doctor or artist who can work anywhere. And to have willing female partners including a gorgeous wife who wants to be friends with the gorgeous mistress. All of those other people in Prague, were they feeling so light in 1968?

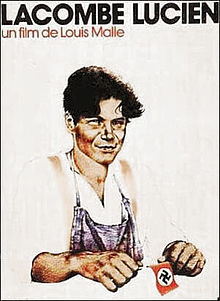

“Lightness” will clumsily demonstrate the failings of the pursuit of hedonism, that reality is going to infringe on even the most fortunate lives, and that appreciating simple pleasures will be one’s greatest reward. There could be a message, as in “Lacombe, Lucien,” about how everyday life conforms, and doesn’t conform, to global politics, but there really isn’t. One of the curiosities of “Lightness” is the Soviet occupation. This is hardly like the crews in “Z” or “Missing.” It’s more reminiscent of the Nazis in “Casablanca.” No one is rounded up or executed. Tomas is regarded more as a nuisance than an enemy. He is told that to continue as a brain surgeon, he must sign an apology for a critique he wrote of communism. He embarrasses the Soviets with his defiance but still isn’t sent to Siberia. Rather, he can wash windows, or join a farm.

One of the strongest films ever made about a three-pronged relationship is “The Mother and the Whore” (“La maman et la putain”), the 1973 French New Wave work by Jean Eustache also related to 1968, but the Paris version. That film is built around three people. They sleep together and express disdain for traditional society, whereas the characters in “Lightness” are older and keep their distance. The exception is when Tereza and Sabina will take pictures of each other, an adventurous scene that probably got the most planning time of Nykvist as any. “Lightness” will curiously try to introduce a fourth person, whose impact is to knock Sabina out of the picture, to the point her closing declaration will sound like a stretch.

And that’s what finally clicks. The first hour of “Lightness,” in which the point will be hammered home that Tomas will pick up a woman every day for sport, struggles to find footing. The story takes flight once Sabina is no longer a distraction, despite being the film’s most vibrant character by far, making “Lightness” a somewhat rare film in that the second half is better than the first. Still, because Nykvist is mostly interested in bedrooms, “Lightness” struggles in its transitions from Prague to Geneva. One seems kind of like the other.

Pets are a curiosity of “Lightness.” They are a part of the novel but seem like add-ons to the movie, almost like someone just said “Hey it worked in ‘Benji.’” Or even “Green Acres.” The humans’ bonds with pets in “Lightness” are, in fact, the strongest bonds in the movie. There is certainly a message here that humans are expendable, animals much less so.

Day-Lewis and Binoche just a few years later probably would’ve put a stronger stamp on “Lightness.” They are perfect for the bedroom but could not make these characters as necessary as most others in their voluminous credits, including “Blue” and Day-Lewis’ masterpiece, “Phantom Thread,” the greatest film of the 2000s. Day-Lewis in “Lightness” actually resembles John Travolta. Olin is the performer who thrives here. Her posing is what gives the movie life. Her impressive ledger includes Bergman’s “Fanny and Alexander.” She also appeared with Binoche in “Chocolat.” Olin’s strength in “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” is not overlooked. In 2019, she and Kaufman attended a screening at the Mill Valley Film Festival.

Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel both put “Lightness” on their Best Films of 1988 list. Ebert gave it a four-star review. Curiously, the Chicago Tribune’s regular critic of the time, Dave Kehr, was not nearly as impressed, handing out two stars. He said “it very nearly is unbearable” and “The film has no vision and no life” and is about a “bad man from the city redeemed by ... noble peasantry.” Kehr says, like Siskel & Ebert, that the film “styles itself” perhaps as a “Last Tango in Paris” of the 1980s but is “just a major imposition.”

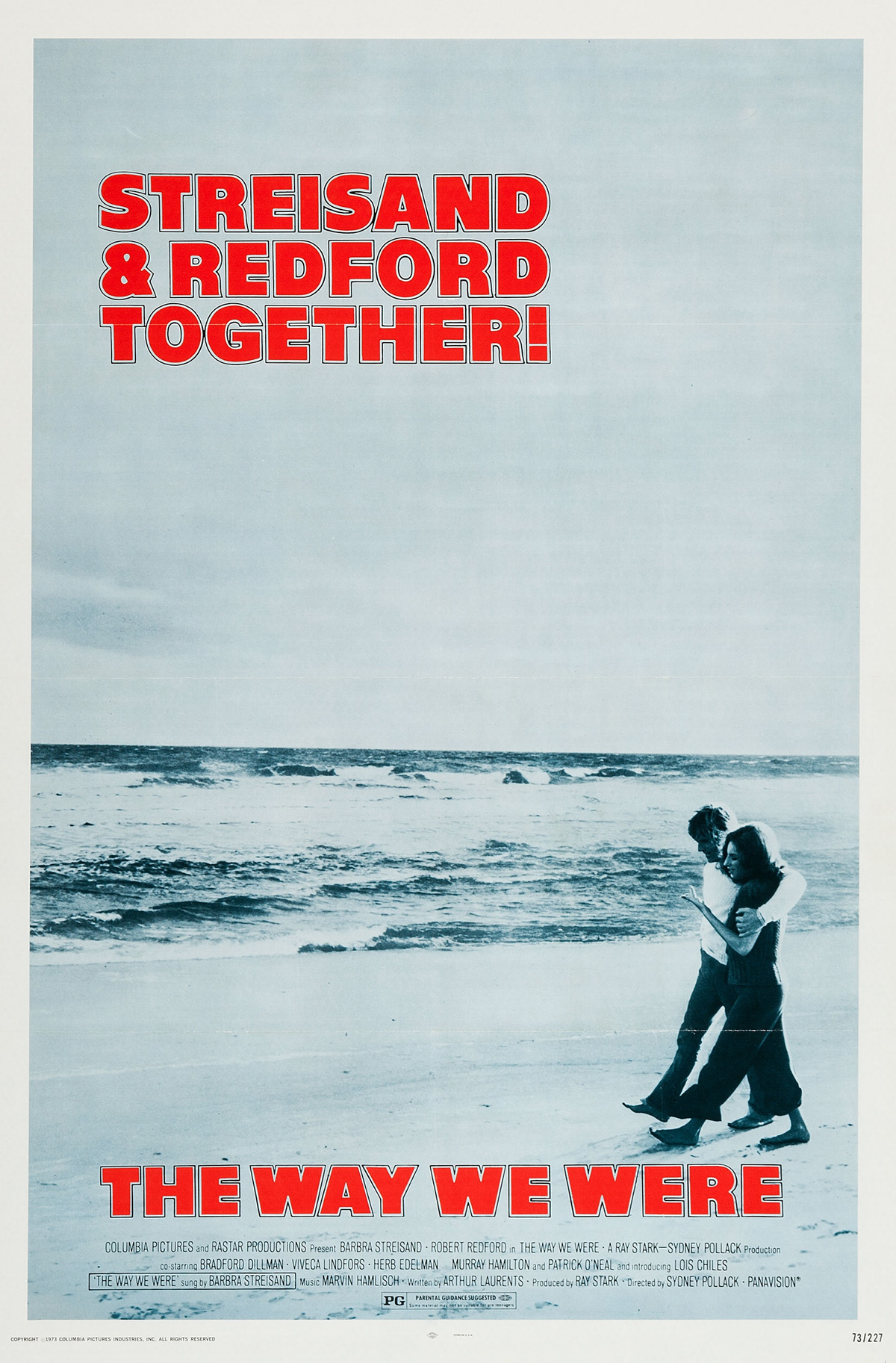

Like “The Way We Were,” “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” is an intended romance about a couple pressured by political events around them that sometimes prove a greater annoyance to the filmmakers than the plot. Things didn’t fit together so neatly in “The Way We Were” either. It’s fondly remembered today because from all the elite talent associated with it, something worked.

For the same reasons, “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” isn’t a fail. It can’t be, not with this kind of talent. Somehow, bookending “Closely Watched Trains,” it foreshadowed change for Czechoslovakia, a year before the Velvet Revolution ended communist rule.

3 stars

(March 2024)

“The Unbearable Lightness of Being” (1988)

Starring

Daniel Day-Lewis

as Tomas

♦

Juliette Binoche

as Tereza

♦

Lena Olin

as Sabina

♦

Derek de Lint

as Franz

♦

Erland Josephson

as The Ambassador

♦

Pavel Landovsky

as Pavel

♦

Donald Moffat

as Chief Surgeon

♦

Daniel Olbrychski

as Interior Ministry Official

♦

Stellan Skarsgard

as The Engineer

♦

Tomek Bork

as Jiri

♦

Bruce Myers

as Czech Editor

♦

Pavel Slaby

as Pavel’s Nephew

♦

Pascale Kalensky

as Nurse Katya

♦

Jacques Ciron

as Swiss Restaurant Manager

♦

Anne Lonnberg

as Swiss Photographer

♦

Laszlo Szabo

as Russian Interrogator

♦

Vladimír Valenta

as Mayor

♦

Clovis Cornillac

as Boy in Bar

♦

Leon Lissek

as Bald Man in Bar

♦

Consuelo de Haviland

as Tall Brunette

♦

Jacqueline Abraham-Vernier

♦

Judith Atwell

♦

Claudine Berg

♦

Jean-Claude Bouillion

♦

Miroslav Breuer

♦

Niven Busch

♦

Margot Capelier

♦

Victor Chelkoff

♦

Monica Constandache

♦

Jean-Claude Dauphin

as Swiss editor

♦

Dominique de Moncuit

♦

Bernard Lepinaux

♦

Josiane Leveque

♦

Peter Majer

♦

Charles Millot

as Lecturer in Geneva

♦

Gerard Moulevrier

♦

Jan Nemec

as Cameraman filming the tanks in Prague

♦

Charly Oleg

♦

Sylvie Plantard

♦

Olga Baïdar Poliakoff

♦

Christine Pottier

♦

Hana-Maria Pravda

♦

Romano

♦

Andre Sanfratello

♦

Jirí Stanislav

♦

Milos Svoboda

♦

Helenka Verner

♦

Marrian Walters

Directed by: Philip Kaufman

Written by: Milan Kundera (novel)

Written by: Philip Kaufman (screenplay)

Written by: Jean-Claude Carrière (screenplay)

Produced by

Producer: Saul Zaentz

Executive producer: Bertil Ohlsson

Associate producer: Paul Zaentz

Music: Mark Adler

Cinematography: Sven Nykvist

Editing: Walter Murch, Vivien Hillgrove, Michael Magill

Co-editor: B.J. Sears

Production design: Pierre Guffroy

Costumes: Ann Roth

Makeup and hair: Paul Le Blanc, Suzanne Benoit, Rosalina Da Silva

Production manager: Daniel Szuster

Unit production manager: USA unit: Frank Simeone

Assistant unit manager: Daniel Baschieri

Stunts: Remy Julienne